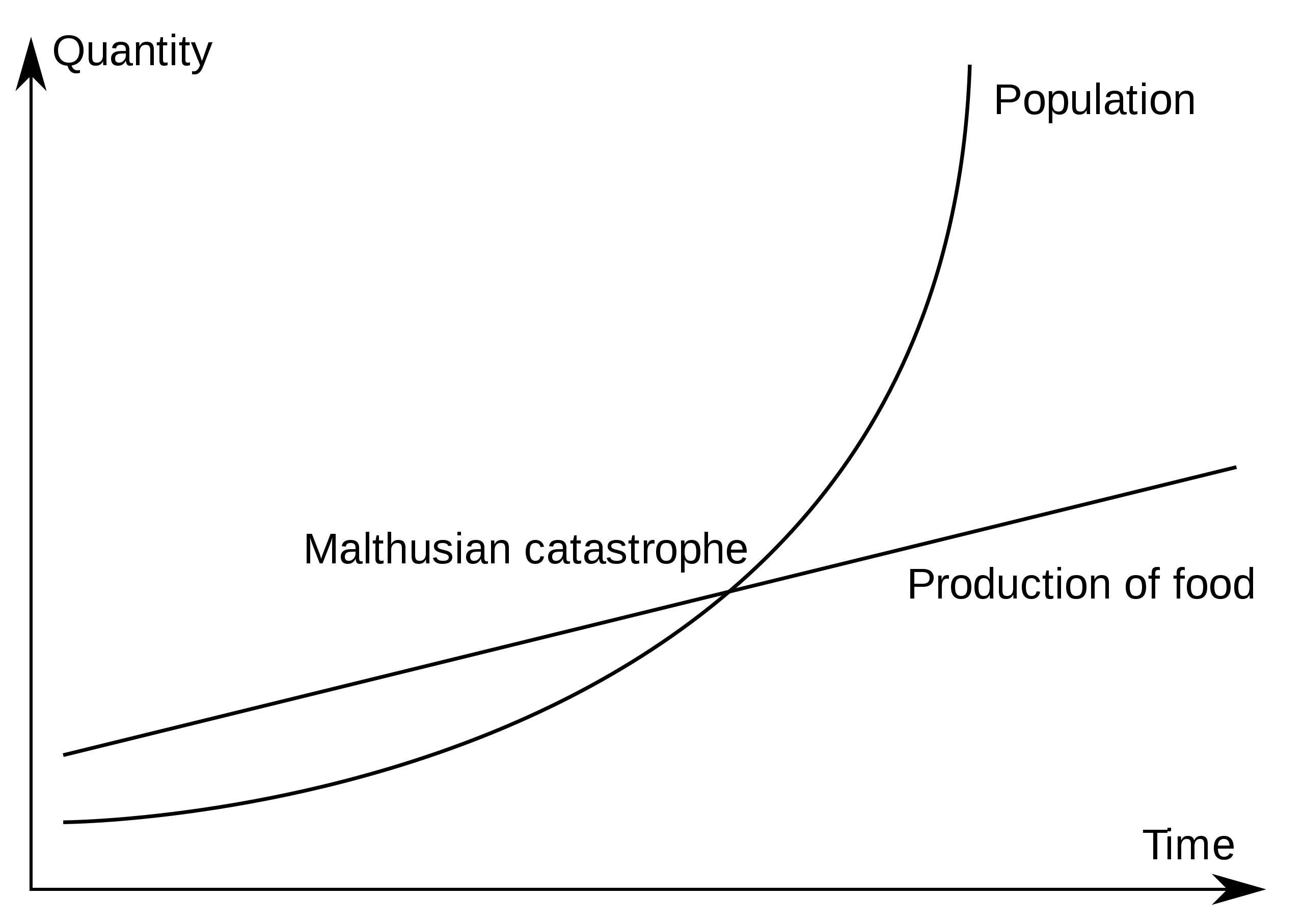

The Malthusian Trap is a famous idea in regards to population pressure. Agricultural progress is linear, population growth is exponential. Inevitably, the population size exceeds the carrying capacity of its farmland. This results in starvation, disease and (civil) war, which reduces the population size. Afterwards, the population can grow again and the cycle repeats.

It's a relatively horrible perspective, and it makes agricultural developments very valuable. Innovate quickly enough, and you can prevent death and war.

Malthus came up with this idea in the 18th century. It led to well-intentioned attempts to spread 'modern' agricultural methods around the world - which did not work, much to the chagrin of many Europeans.

In the 20th century, the Danish economist Ester Boserup came along. She investigated methods of agricultural intensification and concluded that historically, they were terrible. We modern people are used to technological advances being awesome. Modern cars are safer, more efficient and more comfortable than cars from 50 years ago. Modern PCs are cheaper, smaller and more powerful than PCs from 20 years ago. Technology improves our lives.

But that's not true for pre-industrial agricultural tech. The most primitive agricultural method is slash-and-burn agriculture. Take a random piece of forest and burn it. The ashes will make the ground highly fertile. Throw some seeds in there, wait a summer, and crops will grow without much effort. You might be able to use the same plot of land for a couple of years, but then you'll have exhausted the soil. On to the next piece of forest!

The first farmers in an uninhabited area will be able to utilize this method. It'll take roughly thirty years for the forest to regrow, allowing farmers to repeat the cycle. But it does mean that each farmer will need a lot of land.

As the population grows, the land available to each farmer decreases. More crops need to be produced per square meter. Agricultural intensification becomes necessary. Human labor will need to replenish the soil and to optimize yields. The soil will have to be ploughed, manure needs to be spread, weeds need to be removed, perhaps the soil will have to be drained of excess water, or irrigation systems need to be built and maintained.

This is a lot of work. And humans are lazy efficient. So agricultural intensification only happens when population pressure forces farmers to do so. It's not like ploughs were invented and everybody cheered and adopted the idea because ploughing is so much fun. Only when land is scarce and yields need to be improved, humans start to plough. Teach people in low-density areas how to plough and they'll discard your 'innovation' as soon as possible.

From a civilizational perspective, agricultural intensification is great. It allows for higher population densities and the growth of larger cities, and networks of cities. This leads to the specialization of labor and to more advanced technologies. But does it really benefit the individual? If I had to live in 3000BC, I think I'd rather be a farmer in sparsely populated Europe than in a crowded village along the Egyptian Nile.

History Moves North?

I'm Dutch, but our history books in school always start in Egypt. Ancient Egypt, where civilization, writing and religion were invented. Then, in the next chapter, as the timeline progresses, we suddenly jump to Ancient Greece. Then we move towards Ancient Rome, followed by Charlemagne in France around 800AD. Only at the end of the Medieval Period do we really start focussing on the Netherlands and Northern Europe.

That's strange, right? Why does our focus shift so much geographically? Why does it seem to trend towards the north? The books that follow this pattern don't explain why. I wondered about it for a while, but Boserup's theory on the development of agriculture seems to explain a lot of it.

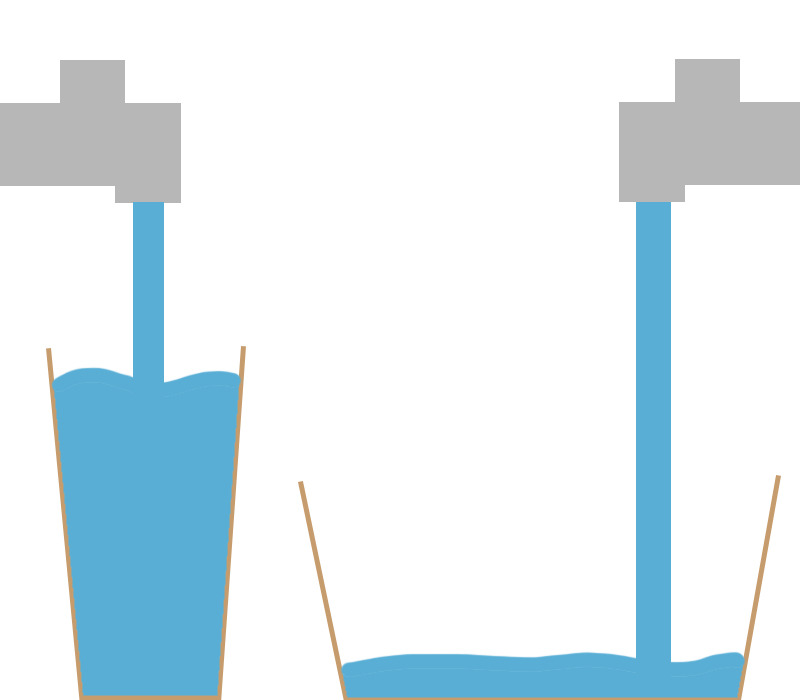

Imagine two water taps filling two different buckets at the same pace. One bucket is narrow, the other is wide.

The narrow bucket will be filled to a higher level quicker than the wide one. Ultimately, the wide one will contain more water. Let's take a look at modern day Egypt from a satellite's perspective.

There's the Nile in the middle, surrounded by a stretch of fertile land, bordered by desert. Imagine being born there in 3000BC. It's crowded and land is scarce. To produce food, you need to work your tiny plot of land very intensively. You could move north or south, but the situation is identical there. You could move to the west or the east, but that's an infertile desert. The logical choice is to work the land intensively.

But compare that to Europe in the same era! The land is fertile and sparsely inhabited in all directions. If a certain area is accidentally densely populated, people are free to move away and lead more relaxed lives with less intense agriculture. Which sounds nice for those individuals, but it does lead to a complete lack of dense cities and related innovations in Europe in that time period.

But the metaphorical Water Tap of Population Growth keeps running and buckets keep filling up. Where does the first European civilization emerge? Not in the wide plains and forests of Germany. It's on the small Greek islands and in the Greek valleys, separated by uninhabitable seas and mountains, where the light of European civilization is kindled.

It's a lot of narrow buckets next to each other. Of course they're the first European buckets where the water reaches a high level!

Explaining the rest of the trend seems relatively obvious. Before Central and Northern Europe "fill up" with intensively worked farmland and a network of cities, it's the Italian peninsula where this process unfolds. When Roman armies conquer northern Europe in the first century BC, they fight rather primitive natives who haven't entered the Iron Age and who cannot write. After the Romans are defeated, the natives build the Palatine Chapel in Aachen around 800AD.

In the same period, European agricultural technology rapidly developed. I'll directly quote Wikipedia:

The Romans achieved a heavy-wheeled mould-board plough in the late 3rd and 4th century AD, for which archaeological evidence appears, for instance, in Roman Britain. The first indisputable appearance after the Roman period is in a northern Italian document of 643. Old words connected with the heavy plough and its use appear in Slavic, suggesting possible early use in that region. General adoption of the carruca heavy plough in Europe seems to have accompanied adoption of the three-field system in the later 8th and early 9th centuries, leading to improved agricultural productivity per unit of land in northern Europe

Remember what we've learned: humans don't adopt more labor-intensive agricultural methods until population pressure forces them to do so. What do late-Roman and Early Medieval Europeans seem to do? Adopt more labor-intensive agricultural methods. Conclusion: the population must have grown. What's the only way to explain firewood/charcoal/forests becoming rarer and more expensive in the late-Roman / Early Medieval Period? A growing population putting more pressure on land.

Modern humans see 'Progress' as a rising tide lifting all boats in all aspects. The population grows, people become wealthier and healthier, they have more spare time, they become more civilized, more educated, more peaceful. It's all connected. So when material wealth diminishes, populations must shrink as well, right?

I don't think we can assume that about the late-Roman and Early Medieval Period. People in brick houses with roof tiles drinking wine from amphorae and eating food from decent earthenware leave a lot of traces.

People in wooden houses with straw roofs drinking beer from wooden barrels and eating food from wooden plates don't. That doesn't mean they did not exist. They could even have been more numerous than their wealthier ancestors. It would certainly explain why fuel became more expensive, and why fuel-intensive practices fell out of use.

So that's my basic theory. Somewhere in the last centuries BCE, the Romans became very successful. They had a network of cities that were properly organized, they built infrastructure, they improved the production of iron and charcoal, and they exploited their environment and less densely inhabited areas effectively.

Their success led to a serious population boom in a large part of Europe. Fertile land per human decreased necessarily. As the population kept growing, fuel became more expensive. Why grow trees for bathhouse fuel, when you can grow crops for your children? In some ways, this is sensible and an improvement above the old situation of a more sparsely populated Europe. In other ways, this is a serious decrease in living standards and a deterioration of civilization. It's not Universal Progress In All Aspects; it's an increase in population density with benefits and drawbacks.

There's a lot more to say about related subjects, but this explains the core of a new perspective on the Fall of Rome. Thanks for reading all of this, and I'd love to hear your opinion.

Previous: The Fall of Rome, II: Energy Problems?

I would point to a different cycle to explain the fall of Rome. Set this against both the Malthusian trap theory and the (many) theories around technology. This is an institutional story.

One of the key problems that the Roman state failed to solve was that of who rules. The Republic was semi-successful at this. It used public recognition and generational advancement in social class as its main methods of controlling elites. This ultimately failed after the Carthaginian wars eliminated the external enemy that kept internal politicking in check. At this point you see a continuous cycle of ambitious elites conquering new territories in the name of Rome and — this is critical — enriching themselves massively and using that fortune to control the Roman state. This led to the civil wars. Ultimately, Octavian triumphed — to my mind, he was the best that Rome could hope for in the circumstances, but he did not really fix the core problem.

After Augustus, the problem became more specific: the succession. The civil wars had shown that the way to control the Roman state was the control armies. Much of later Roman history is essentially a story of charismatic generals fighting for control of the state. It is the interludes in that story that are most important, though. These are when some great general prevails and stays in office long enough to carry out major reforms. Think Diocletian and Constantine.

History books seem to love these “reforms.” Economists hate them. These reforms — unlike those of Augustus — were entirely about capturing more resources for the state, so that the victorious general and his descendants would be better able to fend off competitors. But even the best of Roman’s economy did not produce massive surpluses. So extracting more was difficult. Near the end, the cost of empire was greater for taxpayers than the benefits. This explains why laws would literally mandate that every son follow his father’s occupation using his father’s property: so that the tax man would know from whom to collect. This eventually becomes feudal serfdom, where peasants were tied to the land.

In a setting where private initiative is so burdened with crushing taxation and repressive regulation, is it a surprise that economic growth reverses or that technological innovation becomes limited to agriculture?

I think that this story has more explanatory power than the energy-constraint story does. But it might compound the energy-constraint story. One of the fundamental problems with seeing energy constraint as the empire-killer is that scarcity of a resource should drive up its price. That should incentivize lots of interesting behaviors: long-distance trade, product substitution, process substitutions for technologies that use less of the resource, etc. We see this in the industrial age’s move from charcoal to coal to oil to electricity. We don’t see that in Roman times. Why? Perhaps because the central government fixed the prices of everything so that it would be easier to collect taxes. If the price of charcoal doesn’t increase when supply decreases, we miss out on all of the incentives that a freer market would have brought.

So governing institutions are a key component of why Rome fell, because they caused a ratchet effect of ever-increasing tax and regulatory burdens.

This causes me worry about modern politics. On a precautionary principle, it seems to me that we should look askance at the ever-increasing regulatory burdens on business. If they cause civilization to be less effective at producing technology that can save civilization from whatever would cause its fall (asteroid, supervolcano, disease, global warming, whatever), that seems like a bad deal. The fact that, after a fall from civilization, humanity cannot climb the same ladder it did before because it has exhausted all surface-level minerals means that —unlike Rome — this is probably our last shot at assuring super-long-term survival of the human species. So I'd prefer less regulation that we currently endure.

I should note that my final conclusion highly correlates with my priors, so is suspect.