Crossposted from Substack

"These are my principles. If you don't like them… well, I have others” - G.Marx

Consider this scenario: In a small rural town, a sheriff harbors a hidden prejudice against a Mongolian family—the only one in his jurisdiction. While outwardly professional, he scrutinizes them with unusual severity. Minor infractions lead to tickets or warnings. Their complaints face curt dismissal. Every encounter undergoes hypercritical evaluation.

When the family eventually confronts the sheriff, he responds with righteous indignation: "I simply enforce the law. Your family repeatedly violates traffic regulations and local ordinances."

The family points out that other townspeople commit identical infractions without consequence.

His response? "That's whataboutism. We're discussing your behavior, not other residents. This deflection technique doesn't absolve you of responsibility."

This exchange reveals a pervasive mechanism: pseudo-principality—the selective application of principles based solely on whether they advance one's concealed interests while maintaining a facade of consistent ethical behavior. The sheriff constructs a moral Potemkin village—a facade of principles with nothing behind it. He weaponizes accusations of "whataboutism" as a shield, framing the family's legitimate question about consistency as a mere logical fallacy to deflect the most direct test of his supposed principles.

This pattern is fractal, appearing at every level from personal interactions to international politics.

The Mechanism: Moral Shields and Rhetorical Deflection

Pseudo-principality functions through a two-layer defensive structure:

- Moral Shield: It adopts the language and posture of universal principles—justice, safety, freedom, fairness—creating an appearance of ethical high ground.

- Rhetorical Countermeasures: When challenged on inconsistent application, it deploys tactics like dismissing the challenge as "whataboutism," a red herring, or irrelevant, thereby deflecting scrutiny.

This creates a double-bind for critics: point out inconsistency, and you're accused of a logical fallacy; question the principle itself, and you're attacking something inherently good. This works partly because many lack clear language to distinguish real principles from their counterfeit forms, often compounded by a degree of self-deception. Many practitioners genuinely believe they hold the principles they profess, blinded by motivated reasoning to their own selective application. This sincerity makes their performance convincing.

Why Real Principles Matter (And Why They're Routinely Undermined)

What are principles, really? When I talk about principles here, I specifically mean moral principles – those foundational beliefs about right and wrong that guide behavior. They establish the rules of engagement making social interaction possible without resorting to raw power. Without them, society risks devolving into a "law of the jungle" where only strength matters, and the powerful impose their will without constraint. True principles, applied consistently, form the shared moral architecture that allows civilization itself to flourish, preventing chaos or structural oppression.

Much pseudo-principality stems from an unspoken assumption: principles apply fully to us but not necessarily to them. People who believe "killing is wrong" may support war, implicitly limiting the principle's scope. Few openly state, "These rules are only for my group"; instead, they present principles as universal while applying them selectively.

“I against my brother. I and my brother against my cousin. I, my brother, and my cousin against the world” - Bedouin proverb

This creates a fundamental paradox: principles primarily constrain the powerful, giving them strong incentives to undermine consistent application while maintaining a principled facade. The slaveholder wants freedom for himself but chains for others. The autocrat demands free speech for supporters while silencing critics.

This dynamic suggests many people, consciously or not, effectively prefer the jungle—as long as they get to be the predators. They desire inconsistent application because it grants privilege without responsibility, allowing appeals to fairness only when disadvantaged.

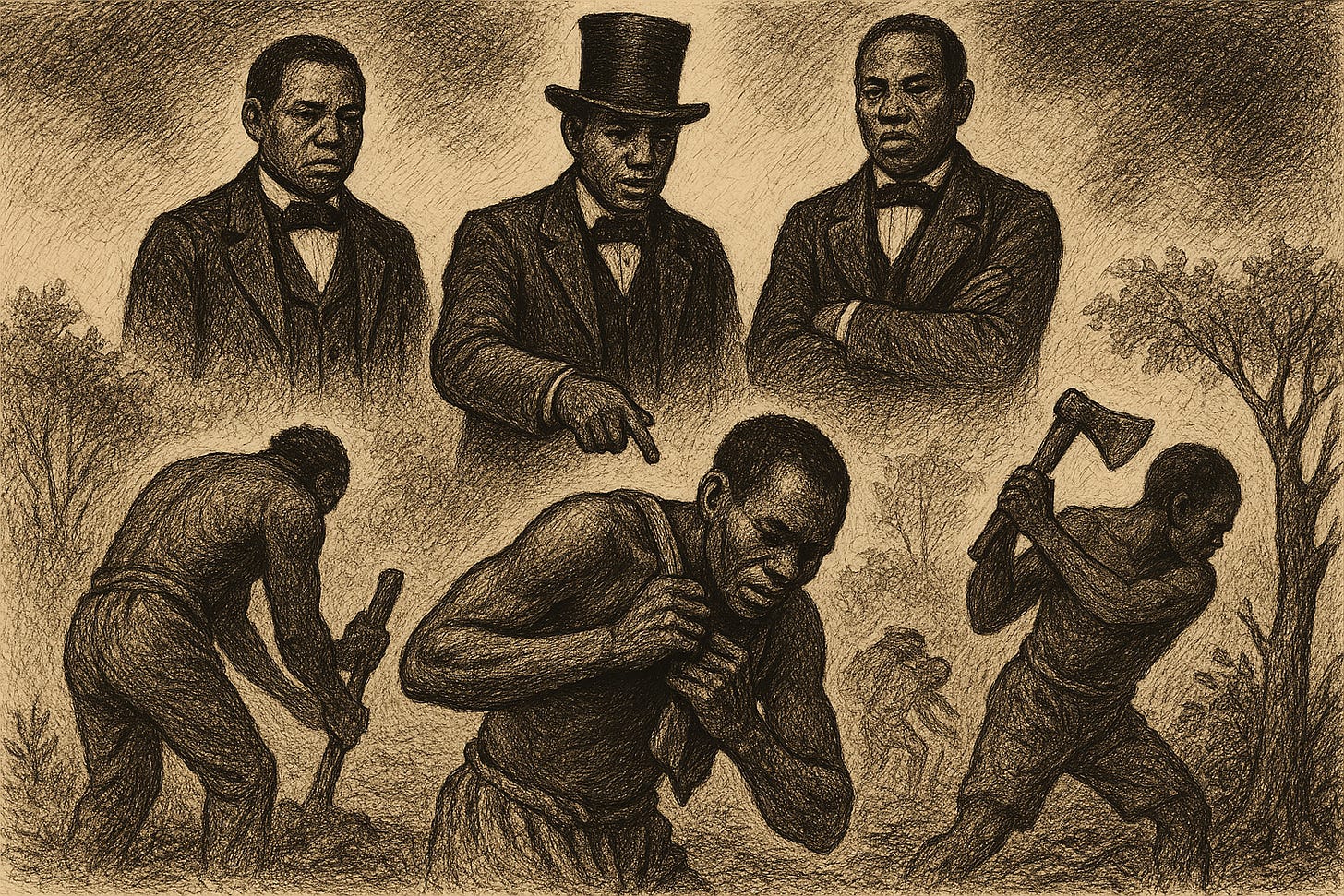

Consider the founding of Liberia. Beginning in the 1820s, former slaves from the United States migrated to West Africa seeking freedom from racial oppression. Yet, instead of extending the universal ideals of liberty they cherished, the resulting Americo-Liberian elite established a political order that excluded the indigenous majority, denied land rights, and even subjected them to forms of forced labor eerily reminiscent of the slavery they had escaped. Once in power, proclaimed principles succumbed to perceived group interest.

Powerful groups throughout history recognize this tension. Openly discarding principles erodes essential social trust, but consistently applying them limits dominance. Thus, the elaborate facades and the strange situation where nearly everyone claims to value principles, yet few apply them consistently.

Institutional Manifestations & Historical Examples

Pseudo-principality isn't just personal; it scales up through institutions:

- Economic Interests: Consider manufacturing associations passionately advocating for stringent "consumer safety" regulations on foreign competitors while simultaneously lobbying against identical standards for domestic production. When challenged, they insist the foreign and domestic contexts are "fundamentally different"—a classic deflection. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 provides another historical example: lawmakers claimed the principle of "protecting American workers" while primarily shielding specific, politically connected industries, using the principle as convenient cover.

- State Power & Colonialism: The Colonial era offers another illustration. European powers developed intricate legal and philosophical doctrines asserting the sanctity of their territorial sovereignty. Yet, these same powers systematically invaded, partitioned, and governed vast regions globally, dismissing nearly identical sovereignty claims made by indigenous peoples. When African kingdoms like the Ashanti or Zulu, or Native American nations, invoked treaties or diplomatic norms based on the Europeans' own frameworks, their arguments were often brushed aside as naive or reflecting a lack of "civilizational maturity"—justifying conquest through pseudo-principality.

What connects these cases isn't simple hypocrisy, but the specific mechanism of pseudo-principality: principles invoked selectively for advantage, under a guise of universality, with consistency challenges deflected.

Rethinking "Whataboutism": The Principle Consistency Challenge

The primary tool for exposing pseudo-principality—challenging inconsistent application—has been largely neutralized by the dismissive label "whataboutism."

Originally describing a specific Soviet propaganda tactic (deflecting criticism by pointing to unrelated flaws in the critic's country, aiming for false equivalence or distraction), the term now serves as a convenient, all-purpose shield. Anyone questioning selective morality risks being shut down with this accusation, regardless of the comparison's relevance or the challenger's intent.

To be clear, consistency challenges can be used fallaciously. But given pseudo-principality's prevalence, our default stance should be acceptance, not dismissal. A consistency challenge is often a vital diagnostic tool for probing selective morality. The burden of proof should lie with the person dismissing the challenge: Why is this comparison invalid? Why does the principle apply differently here in a morally relevant way? Without such justification, crying "whataboutism" is merely deflection.

Furthermore, the term "whataboutism" itself is biased—inherently mocking and diminutive, biasing us against a necessary form of moral reasoning. I propose we adopt a more neutral and accurate term: Principle Consistency Challenge (PCC). This reframes the act as a legitimate inquiry into whether stated principles hold up across relevant situations. We can reserve "whataboutism" specifically for bad-faith distractions. When someone earnestly asks, "Why does this principle apply here but not there?", that question deserves respect and engagement, not ridicule. 1

Spotting Pseudo-Principality: The Diagnostic Test

How can you identify it? While Principle Consistency Challenges (PCCs) are a powerful diagnostic, they require access to the person making the claim—and that’s not always possible. So we also need standalone tools that let us spot pseudo-principality from a distance, based on observable behavior patterns and narrative habits. Look for signs like these:

- Selective Application: Principles conveniently invoked only when benefiting the person or their group. (e.g., Demanding transparency from opponents while fighting it for oneself).

- Disproportionate Outrage: Intense moral indignation when opponents transgress, paired with casual dismissal or elaborate justifications when allies do the same. ("It's tactical necessity for us, an existential threat from them.")

- Shifting Standards: Principles that expand or contract depending on convenience. (e.g., Free speech advocates suddenly favoring restrictions on speech they dislike).

- Aggressive Deflection: Hostility, personal attacks, or immediate cries of "whataboutism" in response to PCCs, rather than thoughtful engagement.

- Context Inflation: Excessive appeals to "unique circumstances" to justify inconsistency, especially when those circumstances conveniently align with self-interest.

Temporal Pseudo-Principality

Another subtle and especially insidious form occurs when individuals uphold a principle—like free speech or due process—only until they gain power. Initially, these values are championed passionately because they protect the individual or group from dominant forces. But once that group secures influence, the same principles are quietly set aside or even reversed. This isn’t classic hypocrisy or overt contradiction—it’s a delayed collapse of principle.

A clear historical example is the French Revolution. In its early phases, revolutionaries fiercely defended free speech and civil liberties as moral weapons against monarchy and aristocracy. But once power shifted into their hands, especially during the Reign of Terror, those same ideals were abruptly suppressed. Censorship, purges, and the silencing of dissent became the norm. The principle hadn’t changed—the incentives had. The revolutionaries who once needed protection from oppression became the ones enforcing it.

Because this reversal unfolds over time, it’s harder to catch. There’s no immediate inconsistency—just a transformation that only becomes visible after power is obtained. The principle was never held for its own sake—it was used as a ladder, and kicked away once the top was reached.

To identify this dynamic, we need a broader diagnostic lens. Much like the advice to watch how someone treats waitstaff to gauge character, we can observe whether people uphold principles across different domains, especially when doing so is inconvenient. Do they support other power-limiting norms like transparency or accountability even when it costs them something? If someone loudly champions one noble value but routinely violates others, that’s a strong signal of pseudo-principality in disguise.

Prevalence & Incentives: The Counterfeit Currency of Morality

Let's be blunt: pseudo-principality isn't fringe; it often seems like the default mode in politics, business, and even personal life. The incentives are powerfully skewed: appearing principled grants social status and moral authority, often with far less cost and inconvenience than being consistently principled. It's a game almost everyone plays, consciously or unconsciously.

This pervasiveness raises a provocative question: If economists try to estimate the percentage of counterfeit currency in circulation, what percentage of publicly stated principles are functionally "counterfeit"—applied selectively for gain? Based purely on observation (admittedly not rigorous data), I'd provocatively guess it's the vast majority—perhaps 80%.

If this estimate is even directionally accurate, then when someone makes a principled claim, we should treat it like potentially counterfeit currency in a medieval market: test it. Bite the coin. Ask how the principle applies in other relevant, especially inconvenient, situations. Provisional skepticism isn't destructive cynicism; it's necessary due diligence in a world saturated with performative morality.

Some Closing Thoughts

Most tools—rhetorical, technological, or institutional—are neutral. They amplify power, regardless of intent. But a rare class of tools tilts the field—they disproportionately help the principled, and break down when used performatively.

Reputation systems are one example. Take online marketplaces like Airbnb or restaurant review platforms: good hosts or service providers who treat people well consistently tend to earn positive reviews. Over time, their reputation compounds into trust and visibility. But opportunistic actors—those who cut corners, mistreat guests, or fake sincerity—can’t maintain that façade for long. The system quietly filters for integrity by design.

Principle Consistency Challenges (PCCs) operate the same way. They’re not neutral tests. They favor people who apply principles broadly and consistently, and disfavor those who use values as situational tools. The more symmetrical scrutiny is applied, the more the principled gain trust—and the more the performative lose power. That asymmetry is what makes PCCs especially valuable.

By reclaiming these challenges, we shift focus from speculation about motives to observable behavior. It gives principled people a reliable method to test motives, identify integrity, and push back against moral theater.

So when someone dismisses a fair challenge as “whataboutism,” pause. Are they defending reason—or protecting a Potemkin virtue that wouldn’t survive a closer look?

One of the most common forms of Whataboutism is of the form "You criticize X, but other people vaguely politically aligned with you failed to criticize Y." (assuming for argument that X and Y are different but similar wrongs)

The problem with that is that the only possible sincere answers are necessarily unsatisfying, and it's hard to gauge their sincerity. Here's what I see as the basic possibilities.

The PCC is a lot more valid when its actually the same person taking inconsistent positions on X and Y. Otherwise your actual interlocutor might not be inconsistent at all but has no plausible way of demonstrating that.