If you set aside the pricing structure and just look at the underlying economics, the power grid will still be definitely needed for all the loads that are too dense for rooftop solar, ie industry, car chargers, office buildings, apartment buildings, and some commercial buildings. If every suburban house detached from the grid, these consumers would see big increases in their transmission costs, but they wouldn't have much choice but to pay them. This might lead to a world where downtown areas and cities have electric grids, but rural areas and the sparser parts of suburbs don't.

There's an additional backup-power option not mentioned here, which is that some electric cars can feed their battery back to a house. So if there's a long string of cloudy days but the roads are still usable, you can transport power from the grid to an off-grid house by charging at a public charger, and discharging at home. This might be a better option than a natural-gas generator, especially if it only comes up rarely.

If rural areas switch to a regime where everyone has solar+batteries, and the power grid only reaches downtown and industrial areas... that actually seems like it might just be optimal? The price of disributed generation and storage falls over time, but the cost of power lines doesn't, so there should be a crossover point somewhere where the power lines aren't worth it. Maybe net-metering will cause the switchover to happen too soon, but it does seem like a switchover should happen eventually.

Why is it cheaper for individuals to install some amount of cheap solar power for themselves than for the grid to install it and then deliver it to them, with economies of scale in the construction and maintenance? Transmission cost?

It's not cheaper in reality. Net metering is effectively a major subsidy that goes away pretty much everywhere that solar generation starts to make up a significant fraction of the supply.

Electricity companies don't want to pay all that capital expense, so it makes sense for them to shift it onto consumers up until home solar generation starts approaching daytime demand. After that point, they can discontinue the net metering and push for "smart meters" that track usage by time of day and charge or pay variable amounts applicable for that particular time, and/or have separate "feed in" credits that are radically smaller per kWh than consumption charges (in practice often up to 85% less).

With smart meters and cheaper home battery systems the incentives starts to shift toward wealthier solar enthusiasts buying batteries and selling excess power to the grid at peak times (or consuming it themselves), lowering peak demand at no additional capital or maintenance cost to the grid operators.

In principle the endgame could involve no wholesale generators at all, just grid operators charging fees to net consumers and paying some nominal amount to net suppliers, but I expect it to not converge to anything as simple as that. Economies of scale will still favour larger-scale operations and local geographic and economic conditions will maintain a mixture of types and scales of generation, storage, distribution, and consumption. Regulation, contracts, and other conditions will also continue to vary greatly from place to place.

If the cost of power generation were the main contributor to the overall cost of the system then I think you'd be right: economies of scale and the ability to generate in cheap places and sell in expensive places would do a lot to keep people on the grid. But looking at my bill (footnote [1]) the non-generation costs are high enough that if current trends continue that should flip; see my response to cata, above.

I'm not claiming here that it's currently cheaper, but that it will soon be cheaper in a lot of places. Only 47% of my bill is the actual power generation, and the non-generation charges total $0.18/kWh. That's still slightly more expensive than solar+batteries here, but with current cost trends that should flip in a year or two.

Looking at their breakdown (footnote [1]) it seems to be mostly the cost of getting the electricity to the consumer. Since they're a monopoly, there's not much getting them to be efficient here, operating a high-uptime anything is expensive, and MA is an expensive place to do anything.

These numbers are dictated by the regulator. What mechanism is there to make them have any relation to the real world?

I don't know this area well, but my understanding is that the "generation" portion represents a market where different companies can compete to provide power, while the other portion is the specific company that has wires to my house operating as a regulated monopoly. So while I don't trust the detailed breakdown of the different monopoly charges (I suspect the company has quite a bit of freedom in practice to move costs between buckets) the high-level generation-vs-the-rest breakdown seems trustworthy.

Yes, if we assume that there is a competitive market for generation, price of transmission may prevent grid solar generation from being built. But you asserted that you could learn the cost of transmission from the bill.

Maybe we're meaning different things by "cost"? If a large monopoly spends $X to do Y then even if they're pretty inefficient in how they do Y I'd still describe $X as the cost. We might discuss ways to get the cost down closer to what we think it should be possible to do Y for (changing regulations, subjecting the monopoly to market forces in other ways, etc) but "cost" still seems like a fine word for it?

Even in this last comment you keep making that very distinction. The regulator dictates the price but you assert that you know what the monopoly spends.

If you just want to assert that the current set of regulations are unsustainable, then I agree. But not a single one of the comments reflects a belief that this is the topic, not even any of your comments.

you assert that you know what the monopoly spends.

First, don't we know that? It's a public company and it has to report what it spends.

But more importantly, I do generally think getting a regulated monopoly like this to become more efficient is intractable, at least in the short to medium term.

Maybe you could learn something by looking at the public filings, but you didn't look at them. By regulation, not by being public, it has to spend proportionate to its income, but whether it is spending on transmission or generation is a fiction dictated by the regulator. It may well be that its transmission operating costs are much lower than its price and that a change of prices would be viable without any improvement in efficiency. This is exactly what I would how I would expect the company to set prices if it controlled the regulator: to extract as much money as possible on transmission to minimize competition. I don't know how corrupt the regulator is, but that ignorance is exactly my point.

whether it is spending on transmission or generation is a fiction dictated by the regulator

That's the key place where we disagree: my understanding is that the "generation" charges are actual money leaving the utility for a competitive market, and this is a real division.

The transmission utility is not purely a transmission company. It spends money on both generation and transmission. Some generation charges leave to other companies. This is not a competitive market, but even if it were, it would only give you a bound on the cost of generation and tell you nothing about the cost of transmission.

This started happening in Hawaii, and to a lesser extent in Arizona. The resolution, apart from reducing net metering subsidies, has been to increased the fixed component of the bill (which pays for the grid connection) and reduce the variable component. My impression is this has been a reasonably effective solution, assuming people don't want to cut their connection entirely.

Talking to a friend who works in the energy industry, this is already happening in Puerto Rico. Electricity prices are high enough that it makes sense for a very large fraction of people to get solar, which then pushes prices up even higher for the remainder, and it spirals.

Isn't it basically a policy choice over there to require net metering and thus make it not economical to get your power over the grid?

Many African countries like Nigeria have a problem that nobody builds power plants and an electric grid because there are laws that forbid that limit businesses to provide that service in a profitable way.

It seems like this would mean that Puerto Rico is going to move into having third-world country energy reliability and a requirement for everyone to deal with buying their own generators like people in Nigeria have to do while in total paying more for energy than they would have to pay if energy would be provided in a more centralized fashion.

But with what reliability? If you don't mind going without power (or dramatically curtailed power) a few weeks a year, then you could dramatically reduce the battery size, but most people in high income countries don't want to make that trade-off.

You say solar is getting cheaper, but it is only the panels that are getting cheaper. They will continue to get even cheaper, but this is not relevant to retrofitting individual houses, where the cost is already dominated by labor. As the cost of labor dominates, economies of scale in labor will be more relevant.

Part of them getting cheaper is becoming higher output, which means the same labor cost gets you more power. For example, in 2018 we got 360W panels while in 2024 we got 425W ones. But I agree this isn't the main component.

And so are batteries.

Lithium-ion batteries have gotten a lot cheaper, but batteries in general have not. Lithium ion are just now starting to become competitive with lead acid for non-mobile applications. It's not clear that batteries in general will get significantly cheaper.

It's going to make sense for a lot of houses to go over to solar + batteries. And if batteries are too expensive for the longest stretch of cloudy days you might have, at least here a natural gas generator compares favorably.

In your climate, defection from the natural gas and electric grid is very far from being economical, because the peak energy demand for the year is dominated by heating, and solar peaks in the summer, so you would need to have extreme oversizing of the panels to provide sufficient energy in the winter. But if you have a climate that has a good match between solar output and energy demand, it gets better (or if you only defect from the electric grid). Still, even if batteries got 3 times cheaper to say $60 per kilowatt hour, and you needed to store 3 days of electricity, that would be about $4300 per kilowatt capital cost, which is much more expensive than large gas power plants + electrical transmission and distribution. Another big issue is that reliability would not be as high as with the central grid in developed countries (though it very well could be more reliable than the grid in a low income country).

While a power station could be up to 63% efficient, for a home generator maybe I'm looking at something like the 23% efficient Generac 7171, rated for 9kW on natural gas at full load. Or maybe something smaller, since this is probably in addition to batteries and only has to match the house's average consumption. This turns my $0.06kWh into $0.24/kWh, plus the cost of the generator and maintenance.

Yes, you would only want around 1 kW electrical, especially because the only hope to make this economical when you count the capital cost and maintenance is to utilize a lot of the waste heat (cogeneration), ideally both for heating and for cooling (through an absorption cycle, trigeneration). But though I don't think it works economically for a household (even in your favorable case of low natural gas prices and high electricity prices), you can have an economical cogeneration/trigeneration installation for a large apartment building, and certainly for college campuses.

Battery costs should be lower by now than they are.

For example, in Australia wholesale cell prices are on the order of $150/kW-hr, while installed battery systems are still more than $1000/kW-hr. The difference isn't just packaging, electrical systems, and installation costs. Packaging doesn't cost anywhere near that much, installation costs are relatively flat with capacity, and so are electrical systems (for given peak power). Yet battery system costs from almost all suppliers are almost perfectly linear with energy capacity.

I don't know why there isn't an alternative decent-quality supplier that would eat their lunch on large-capacity systems with moderate peak power. Such a thing should be still very highly profitable with a much larger market. It could be that there just hasn't been enough time for such a market to develop, or supply issues, or something else I'm missing?

That does sound like an excessive markup. But my point is even with the wholesale price, chemical batteries are nowhere near cost-effective for medium-term (days) electrical storage. Instead we should be doing pumped hydropower, compressed air energy storage, or building thermal energy storage (and eventually some utilization of vehicle battery storage because the battery is already paid for for the transport function). I talk about this more in my second 80k podcast.

At $150/kW-hr and assuming a somewhat low 3000 cycle lifetime, such batteries would cost $0.05 per cycled kW-hr which is very much cost-effective when paired with the extremely low cost but inconveniently timed nature of solar power. It would drop the amortized cost of a complete off-grid power system for my home to half that of grid power in my area, for example.

Even now at $1000/kW-hr retail it's almost cost-effective here to buy batteries to time-shift energy from solar generation to time of consumption. At $700/kW-hr it would definitely be cost-effective to do daily load-shifting with the grid as a backup only for heavily cloudy days.

Pumped hydro is already underway in this region, though it's proving more expensive and time-consuming to build than expected. Have there been some recent advances in compressed air energy storage? The information I read 2-3 years ago did not look promising at any scale.

If you have 3 days worth of storage, even if you completely discharge it in 3 days and completely charge it in the next 3 days, you would only go through about 60 cycles per year. In reality, you might get 10 full cycles per year. With interest rates and per year depreciation, typically you would only look out around 10 years, so you might get ~100 discounted full cycles. That's why it makes more sense to calculate it based on capital cost as I have done above. If you're interested in digging deeper, you can get free off grid modeling software, such as the original version of HOMER (new versions you have to pay).

Even now at $1000/kW-hr retail it's almost cost-effective here to buy batteries to time-shift energy from solar generation to time of consumption. At $700/kW-hr it would definitely be cost-effective to do daily load-shifting with the grid as a backup only for heavily cloudy days.

Please write out the calculation.

Have there been some recent advances in compressed air energy storage? The information I read 2-3 years ago did not look promising at any scale.

Aboveground compressed air energy storage (tanks) is a little cheaper than chemical batteries. But belowground large compressed air energy storage is much cheaper for days of storage, with estimates around $1 to $10 per kilowatt hour. Current large installations are in particularly favorable geology, but we already store huge amounts of natural gas seasonally in saline aquifers. So we can basically do the same thing with compressed air, though the cycling needs to be more frequent.

Batteries are primarily used for intra-day time shifting, not weekly. I agree that going completely off grid costs substantially more than being able to use your own generated power for 80-90% of usage. That's why I focused on the case where home owners remain grid-connected in my top-level comment:

With smart meters and cheaper home battery systems the incentives starts to shift toward wealthier solar enthusiasts buying batteries and selling excess power to the grid at peak times (or consuming it themselves), lowering peak demand at no additional capital or maintenance cost to the grid operators.

The only mention I made regarding completely off-grid power systems was about the counterfactual scenario of $150/kW-hr battery cost, which I have not assumed anywhere else. I didn't say that it would be marginally cost effective to go completely off grid with such battery prices, just that it would be substantially more cost-effective than buying all my power from the grid. The middle option of 80-90% reduced but not completely eliminated grid use is still cheaper than either of the two extremes, and likely to remain so for any feasible home energy storage system.

That's what I was referring to regarding $700 kW/hr. At $1000/kW-hr it's (just barely) not worth even buying batteries to shift energy from daytime generation to night consumption, while at $700/kW-hr it definitely is worthwhile. Do you need the calculation for that?

At $1000/kW-hr it's (just barely) not worth even buying batteries to shift energy from daytime generation to night consumption, while at $700/kW-hr it definitely is worthwhile.

Doesn't this depend heavily on local utility rates, and so any discussion of crossover points should include rates? Ex: I'm at $0.33/kWh while a friend in TX is at half that.

Yes, it definitely does depend upon local conditions. For example if your grid operator uses net metering (and is reliable) then it is not worthwhile at any positive price. This statement was in regard to my disputed upstream comment "Even now at $1000/kW-hr retail it's almost cost-effective here [...]".

It would be helpful to see a calculation with your rates, the installed cost of batteries, cost of the space taken up, losses in the batteries and convertor, any cost of maintenance, lifetime of batteries, and cost (or benefit) of disposal.

In your climate, defection from the natural gas and electric grid is very far from being economical, because the peak energy demand for the year is dominated by heating, and solar peaks in the summer, so you would need to have extreme oversizing of the panels to provide sufficient energy in the winter.

I think the prediction here is that people will detach only from the electric grid, not from the natural gas grid. If you use natural gas heat instead of a heat pump for part of the winter, then you don't need to oversize your solar panels as much.

Yes, but the rest of my comment focused on why I don't think defection from just the electric grid is close to economical with the same reliability.

I was under the impression that the biggest cost of grid electricity is stability, that is most of the time the price charged on consumer is much [i.e. about 2x] higher than the average cost on the grid market, but occasionally the grid market price would go up astronomically [ say 1000x] for brief periods of time [say hours], and the household consumer would be insulated from that. I thought that something similar happened in Texas when a cold snap happened?

if you are confident that your battery can hold you over those crunch period I assume you can just import grid energy at grid market price cheaper than the solar can provide [currently you can get paid 0.03/kwh for using electricty at peak solar here is Sydney]. I mean your solar, no matter how cheap, can not beat being given money. or so was the result last I did the math in Australia.

Actually I don't have the number now but the calculation I did suggested that running solar but using the grid as a battery is more cost effective than running your own battery, but my result may not generalise.

I am suprise you can get gas so cheap where you are, in Sydney the cost of electricity is similar to you 0.33/kwh but gas is 0.17/kwh. Have you check if you are receiving some subsidies for it?

Have you check if you are receiving some subsidies for it?

I think natural gas in the US is effectively subsidized by underinvesting in export infrastructure? This country produces a lot of gas.

Before power grid dissolves, it has also to hit factories (and business in general). I don't think resulting price increments are predictable - they might as well start some crisis in economy. (And there might be money-unrelated outcomes, like if restaurants start ignoring some safety standards trying to save on electricity or like, which could be disastrous with habit of eating out.)

When I was growing up most families in our neighborhood had the daily paper on their lawn. As getting your news on the internet became a better option for most folks, though, delivery became less efficient: fewer houses on the same route. Prices went up, more people cancelled, and decline continued. I wonder if we might see something similar with the power grid?

Solar panels keep getting cheaper. When we installed panels in 2019 they only made sense because of the combination of net metering and the relatively generous SREC II incentives. By the time we installed our second set of panels a few months ago net metering alone was enough to make it worth it.

Now, as I've said a few times, net metering is kind of absurd. The way it works here is that most of my bill is in proportion to my net consumption: if I use 100kWh but also send 100kWh back to the grid I don't pay anything for transmission or generation. I can use the grid as a giant battery, for just a $10/month grid-connection charge.

As more people run the numbers and install rooftop solar, I expect there to be increasing pressure to limit net metering, either for new installs or for everyone. But even if net metering were completely phased out it wouldn't solve the problem: as people draw less from the grid the company either needs to raise their per-kWh rates or their per-customer charges. Raise the former and installing solar becomes even more attractive; raise the latter and people start thinking about disconnecting entirely.

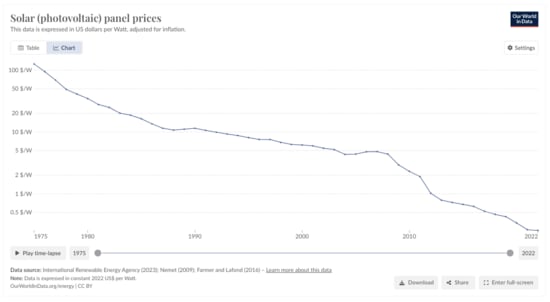

Solar is getting cheaper very quickly:

Our World In DataAnd so are batteries. It's going to make sense for a lot of houses to go over to solar + batteries. And if batteries are too expensive for the longest stretch of cloudy days you might have, at least here a natural gas generator compares favorably.

Wait, really? This was pretty surprising to me, but here's the sketch. My marginal cost of electricity is currently $0.33/kWh [1] vs $0.06/kWh [2] for natural gas. Now I can't charge my laptop with raw gas, which means burning the gas in a generator, and since that's well under 100% efficient I'm not actually getting a usable $0.06/kWh. While a power station could be up to 63% efficient, for a home generator maybe I'm looking at something like the 23% efficient Generac 7171, rated for 9kW on natural gas at full load. Or maybe something smaller, since this is probably in addition to batteries and only has to match the house's average consumption. This turns my $0.06kWh into $0.24/kWh, plus the cost of the generator and maintenance.

If trends continue it looks like we may be pretty close to mass defections from the power grid, which would then accelerate because the utility would need to keep raising prices to cover the same infrastructure with fewer subscribers. This could be especially bad for customers who rent, and so aren't able to install their own system, and people who don't have the savings or credit for a big up-front cost. On the other hand, it's downstream from a more efficient system overall, and maybe we can sort out the distributional impacts?

[1] Here's how that breaks down:

[2] $1.5512/therm / 28 kWh per therm = 0.0554/kWh.