Have you read Joseph Henrich’s books The Secret of Our Success, and its sequel The WEIRDest People in the World? If not, they provide a pretty comprehensive view of how humanity innovates and particularly the Western world, which is roughly in line with what you wrote here.

Then we need a larger city and another English spelling reform to unleash the second industrial revolution!

More seriously, it seems to me that the problem of "not forgetting intellectual work" is mostly solved, but two more problems remain: (1) remove all the bullshit that threatens to drown the intellectual work by sheer persistence and quantity; and (2) make the intellectual work more accessible, reduce the unnecessary inconveniences of education and academia.

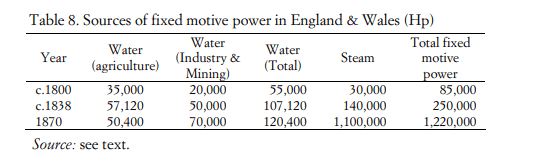

One popular conception of the Industrial Revolution is that steam engines were invented, and then an increase in available power led to economic growth.

This doesn't make sense, because water power and horses were much more significant than steam power until well after technological development and economic growth became fast.

While it is true that the first industrial revolution was largely propelled by water, wind, and horsepower rather than the steam engine, the steam engine was instrumental in continuing that momentum into the latter half of the 19th century. The Dutch Golden Age is sometimes characterized as a kind of proto-industrial revolution and likely saw the highest productivity in history prior to the 1800s. (The Dutch by this time also ticked most of the boxes you listed as causes of industrialization.) This economic revolution, like early British industrialization, relied on wind and water power (along with peat) but eventually hit a wall. Without the steam engine, once the rivers are dammed, the countryside is dotted with windmills, and the easily accessible biomass is depleted, energy availability becomes a major constraint for further growth.

Had a practical steam engine somehow failed to materialize during early industrialization, the first industrial revolution may very well have gone down in the annals of history as just another lost "golden age" like so many economic economic efflorescences before it. A period of high mechanization like the Dutch Golden Age that generated new technologies and vast wealth for a short period before sputtering out.

I'm skeptical that spelling reform moved the needle much. I'm admittedly not super familiar with the subject but the notion that vast swathes of information were lost due to phonetic spelling seems unlikely to me. Intellectuals could always fallback on Latin as a lingua franca until shortly before industrialization. Striking that entry from your industrialization checklist, the obvious next question becomes "Why Britain?", as many other European states met the other requirements, yet not only failed to industrialize before Britain but even struggled to follow Britain's progression. Industrialization in The Netherlands would not really take off in earnest until nearly a century after the first textile factories opened on the other side of the North Sea.

Had a practical steam engine somehow failed to materialize during early industrialization, the first industrial revolution may very well have gone down in the annals of history as just another lost "golden age"

No, it would have been entirely possible to skip steam piston engines and go directly from water wheels to internal combustion engines, large steam turbines, and/or hydroelectric power.

All of three technologies you've listed were not ready for broad practical use until well over 150 years after Newcomen's steam engine. By this time, steam power had long since dethroned wind and water as the primary source of energy for industrial production.

https://histecon.fas.harvard.edu/energyhistory/data/Warde_Energy%20Consumption%20England.pdf

By the mid 1800s, steam was producing as much power for England and Wales as all other sources of fixed motive power combined. That's not even mentioning the world changing impact of inventions such as the train and steamship. Now consider a world without this technology. What leads you to believe that a practical ICE, large steam turbine, and/or hydroelectric power would develop even remotely on schedule in a world with no trains, far lower steel production, and half the motive power? The steam engine's impact on early industrialization is often overstated but its impact by 1850 really can't be exaggerated. It was the diffusion and improvement of the steam engine that bridged the economic gap between the first and second industrial revolution.

How many horses were there?

Also, development of those 3 technologies wasn't limited by available power.

How many horses were there?

Well over a million in England by 1850. However they were used primarily for agriculture and later transport. Not industry. As such, they played, at most, a supporting role in industrialization. Also, my original question stands, "Why England?", given the Dutch Golden Age had similar conditions.

Also, development of those 3 technologies wasn't limited by available power.

No, but they were limited by technological advancement and production getting cheaper, which by the mid 1800s were very much tied to steam power. They were also limited by the availability of capital for development, capital which would be much harder to come by with less energy to begin with. And of course the steam turbine was developed directly from the steam engine.

Why did the Industrial Revolution happen when it did? Why didn't it happen earlier, or in China or India? What were the key factors that weren't present elsewhere?

I have a theory about that which I haven't seen before, so I thought I'd post it.

steam power

One popular conception of the Industrial Revolution is that steam engines were invented, and then an increase in available power led to economic growth.

This doesn't make sense, because water power and horses were much more significant than steam power until well after technological development and economic growth became fast. (Also, steam engine designs wouldn't have caused economic growth in Ancient Rome because manufacturing them wasn't practical at the time.) Steam power being the key factor is now considered a discredited view by most historians.

agriculture

Agricultural productivity in Europe improved significantly before the Industrial Revolution, and rapidly during it. Improvements included:

This reduced the number of farmers needed, potentially allowing more people to do research, or other kinds of work with more available technological improvement.

More people doing research can certainly make it go faster, but there were already intellectuals and a leisure class before the Industrial Revolution. The increase in tech development was disproportionate to the non-farmer population. The UK population also increased, but it was still a relatively small fraction of the world population, and most of its population growth happened after 1800.

canals

Britain made a large canal system that enabled funneling food to London. Combined with agricultural progress, this enables a large city, and London was the largest city in the world starting in around 1830.

But by 1830, the Industrial Revolution was already well underway. There were already large cities such as Beijing well before that point, so "a large city" was not the only key factor.

my theory

My view is that the Industrial Revolution happened due to the combination of:

culture

If you look at the inventions of ancient China and ancient Mesopotamia, I think there was less emphasis on practicality and usage by the common people. For example, al-Jazari largely made toys for the wealthy, and Zhang Heng made tools for astrology.

Europe had a long history of continuous warfare, and unskilled labor was less available than in China. I think that led to a greater emphasis on practicality of inventions.

intellectual tools

The Gutenberg Press was invented around 1440. That made it possible to spread written works much more widely and with fewer mistakes, making communication faster and reducing the chance that progress would be lost.

Fibonacci brought Arabic numerals to Europe around 1200, but they remained rare until after 1450. Between 1470 and 1550, they were spread rapidly by the printing press. Engineering requires multiplication, and multiplication is much easier with Arabic numerals than Roman numerals. That change made calculations faster and reduced their error rates.

The introduction of the printing press also drove standardization of English spelling. Originally, written English words didn't directly represent meanings; rather, sounds/pronunciations were linked to meanings, and different people had various ways of representing those pronunciations with letters. That spelling standardization reduced the chances of misreading words and made reading faster.

error rates and exponentials

Consider a model where knowledge (K) accumulates or decays exponentially over time, and is also developed with diminishing returns, such as:

If (a, b, c) are such that the exponent of knowledge accumulation is positive for smart individuals but negative for interpersonal communication in a society, then K reaches an equilibrium value, with occasional peaks from a rare genius or intellectual society, but that progress later decaying due to imperfect communication and preservation.

The printing press made intellectual work less likely to be lost. Arabic numerals made calculation errors less likely. Spelling standardization made misreading text less likely. My theory of the Industrial Revolution is that those factors collectively reduced the decay of knowledge enough that the exponent for societal-level knowledge growth went significantly positive up to much higher levels of intellectual progress.

Then, knowledge accumulated exponentially in the UK from 1500 to 1800. This led to agricultural productivity increasing from around 1525, and eventually to the accumulation of enough societal knowledge for the Industrial Revolution.