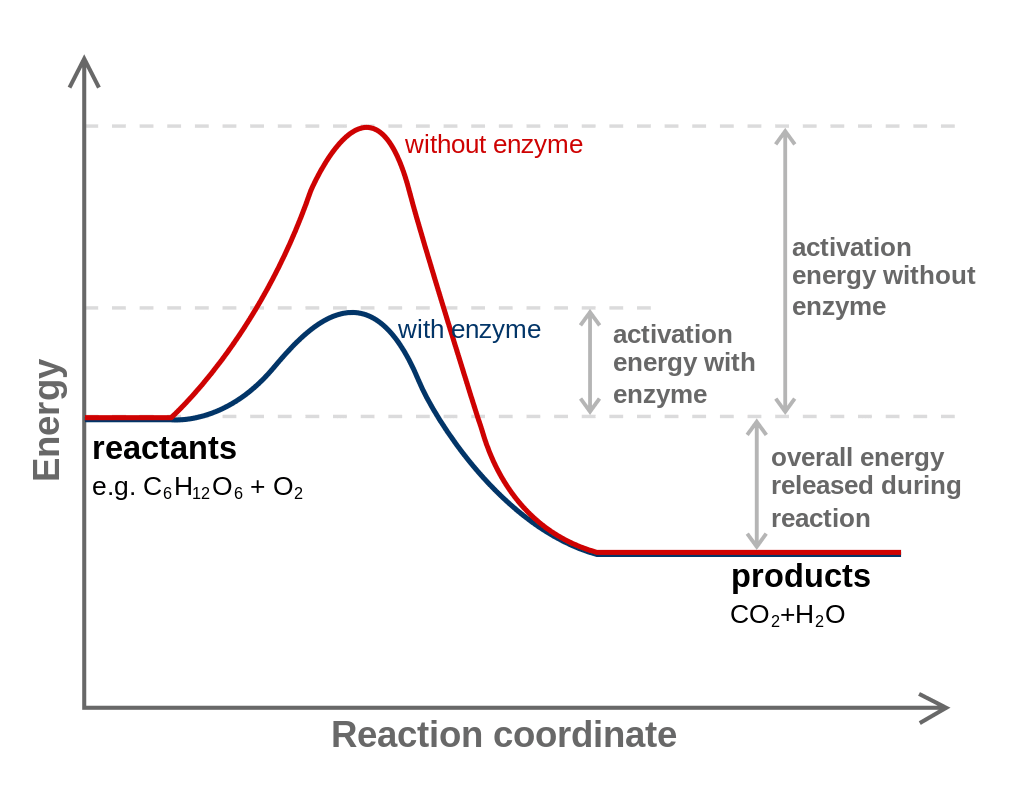

This is a diagram explaining what is, in some sense, the fundamental energetic numerical model that explains "how life is possible at all" despite the 2nd law:

The key idea is, of course, activation energy (and the wiki article on the idea is the source of the image).

If you take "the focus on enzymes" and also the "background of AI" seriously, then the thing that you might predict would happen is a transition on Earth from a regime where "DNA programs coordinate protein enzymes in a way that was haphazardly 'designed' by naturalistic evolution" to a regime where "software coordinates machine enzymes in a way designed by explicit and efficiently learned meta-software".

I'm not actually sure if it is correct to focus on the fuel as the essential thing that "creates the overhang situation"? However fuel is easier to see and reason about than enzyme design <3

If I try to think about the modern equivalent of "glucose" I find myself googling for [pictures of vibrant cities] and I end up with things like this:

You can look at this collection of buildings like some character from an Ayn Rand novel and call it a spectacularly beautiful image of human reason conquering the forces of nature via social cooperation within a rational and rationally free economy...

...but you can look at it from the perspective of the borg and see a giant waste.

So much of it is sitting idle. Homes not used for making, offices not used for sleeping!

Parts are over-engineered, and many doubly-over-engineered structures are sitting right next to each other, since both are over-engineered and there are no cross-spars for mutual support!

There is simply a manifest shortage of computer controlling and planning and optimizing so many aspects of it!

I bet they didn't even create digital twins of that city and run "simulated economies" in digital variants of it to detect low hanging fruit for low-cost redesigns.

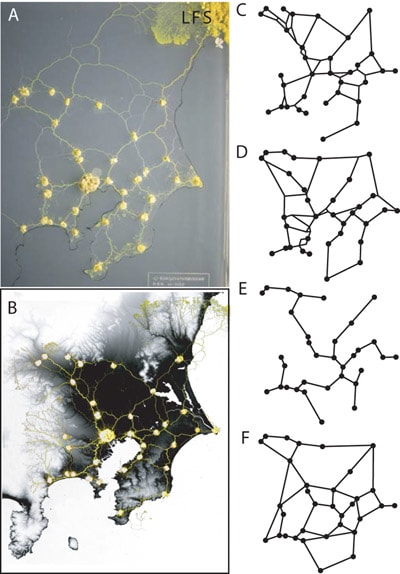

Maybe at least the Tokyo subway network was designed by something at least as smart as slime mold, but the roads and other "arteries" of most other "human metaorganic conglomerations" are often full of foolishly placed things that even a slime mold could suggest ways to fix!

(Sauce for Slime Mold vs Tokyo.)

I think that eventually entropy will be maximized and Chaos will uh... "reconcile everything"... but in between now and then a deep question is the question of preferences and ownership and conflict.

I'm no expert on Genghis Khan, but it appears that the triggering event was a triple whammy where (1) the Jin Dynasty of Northern China cut off trade to Mongolia and (2) the Xia Dynasty of Northwest China ALSO cut off trade to Mongolia and (3) there was a cold snap from 1180-1220.

The choice was probably between starving locally or stealing food from neighbors. From the perspective of individual soldiers with familial preferences for racist genocide over local tragedy, if they have to kill someone in order to get a decent meal, they may as well kill and eat the outgroup instead of the ingroup.

And from the perspective of a leader, who has more mouths among their followers than food in their granaries, if a war to steal food results in the deaths of some idealistic young men... now there are fewer mouths and the angers are aimed inward and upward! From the leaders selfish perspective, conquest is a "win win win".

Even if they lose the fight, at least they will have still redirected the anger and have fewer mouths to feed (a "win win lose") and so, ignoring deontics or just war theory or property rights or any other such "moral nonsense", from the perspective of a selfish leader, initiating the fight is good tactics, and pure shadow logic would say that not initiating the fight is "leaving money on the table".

From my perspective, all of this, however, is mostly a description of our truly dark and horrible history, before science, before engineering, before formal logic and physics and computer science.

In the good timelines coming out of this period of history, we cure death, tame hydrogen (with better superconductors enabling smaller fusion reactor designs), and once you see the big picture like this it is easier to notice that every star in the sky is, in a sense, a giant dumpster fire where precious precious hydrogen is burning to no end.

Once you see the bigger picture, the analogy here is very very clear... both of these, no matter how beautiful these next objects are aesthetically, are each a vast tragedy!

(Sauce.)

(Sauce.)

The universe is literally on fire. War is more fire. Big fires are bad in general. We should build wealth and fairly (and possibly also charitably) share it, instead of burning it.

Nearly all of my "sense that more is possible" is not located in personal individual relative/positional happiness but rather arises from looking around and seeing that if there were better coordination technologies the limits of our growth and material prosperity (and thus the limits on our collective happiness unless we are malignant narcissists who somehow can't be happy JUST from good food and nice art and comfy beds and more leisure time and so on (but have to also have "better and more than that other guy")) are literally visible in the literal sky.

This outward facing sense that more is possible can be framed as an "AI overhang" that is scary (because of how valuable it would be for the AI to kill us and steal our stuff and put it to objectively more efficient uses than we do) but even though framing things through loss avoidance is sociopathically efficient for goading naive humans into action, it is possible to frame most of the current situation as a very very very large opportunity.

That deontic just war stuff... so hot right now :-)

Since we are at no moment capable of seeing all that is inefficient and wasteful, and constantly discover new methods of wealth creation, we are at each moment liable to be accused of being horribly wasteful compared to our potential, no? There is no way to stand up against that accusation.

Note, though, that agrarian Eurasians empires ended up winning their 1000 thousand years struggle against the steppe peoples.

Yes, and I believe that the invention and spread of firearms was key to this as they reduce the skill dependence of warfare, reducing the advantage that a dedicated warband has over a sedentary population.

That, but getting your army from mostly melee to mostly range and solving your operational problems helps a lot too.

That story of Mongol conquests is simply not true. Horse archer steppe nomads existed for many centuries before Mongols, and often tried to conquer their neighbors, with mixed success. What happened in the 1200s is that Mongols had a few exceptionally good leaders. After they died, Mongols lost their advantage.

Calling states like Khwarazmian or Jin Empire "small duchies" is especially funny.

What happened in the 1200s is that Mongols had a few exceptionally good leaders

It's consistent with the overhang model that a new phase needs ingredients A, B, C, ... X, Y, Z. When you only have A, ... X it doesn't work. Then Y and Z come, it all falls into place and there's a rapid and disruptive change. In this case maybe Y and Z were good leaders or something. I don't want to take too strong a position on this, as given my research it seems there is still debate among specialists about what exactly the key ingredients were.

The implication: overhangs CANNNOT be measured in advance (this is like a punctuated equilibrium model); they are black swan events. Is that how you see it?

Well, sometimes they can, because sometimes the impending consumption of the resource is sort of obvious. Imagine a room that's gradually filling with a thin layer of petrol on the floor, with a bunch of kids playing with matches in it.

Could an alien observer have identified Genghis Khan's and the Mongol's future prospects when he was a teenager?

I'm not quite sure.

No, because the events which led to the unification of the Mongol tribes by Gengis Khan were highly contingent.

However, the military power overhang of the steppe peoples vs agrarian states should have been obvious for anyone since both the Huns and the Turks did the same thing centuries before.

Could an alien observer have identified Genghis Khan's and the Mongol's future prospects

Well, probably not to that level of specificity, but I think the general idea of empires consuming vulnerable lands and smaller groups would have been obvious

As well as being fast/violent/disruptive, these changes tend to not be good for incumbents.

This also probably happened in the US after the emergence of nuclear weapons, the Revolt of the Admirals. I'm pretty sure that ~three top US generals died under mysterious circumstances in the period after WW2 before US-Soviet conflict heated up (my research skills weren't as good when I looked this up 3 years ago).

I wouldn't be surprised if a large portion of the NSA aren't currently aware of the new psychology paradigm facilitated by the combination of 2020s AI and the NSA's intercepted data (e.g. enough video calls to do human lie detection research based on facial expressions) because they don't have the quant skills to comprehend it, even though it seems like this tech is already affecting the US-China conflict in Asia.

Yes, although I did this research ~3 years ago as an undergrad, filed it away, and I'm not sure if it meets my current epistemic/bayesian standards; I didn't read any books or documentaries, I just read the tons of Wikipedia articles and noted that the circumstances of these deaths stood out. The three generals who died under suspicious circumstances are:

- James Forrestal, first Secretary of Defense (but with strong ties to the Navy during its decline), ousted and died by suicide at a military psychiatric hospital during the Revolt of the Admirals at age 57 in May 1949. This is what drew my attention to military figures during the period.

- George Patton, the top general of the US occupation forces in Germany, opposed Eisenhower's denazification policy of senior government officials due to concerns that it would destabilize the German government (which he correctly predicted would become West Germany and oppose the nearby Soviet forces). Ousted and died in a car accident less than 6 months later, in December 1945.

- Hoyt Vandenberg, Chief of staff of the Air Force, retired immediately after opposing Air Force budget cuts in 1953 when the Air Force was becoming an independent branch from the Army and a key part of the nuclear arsenal. Died 9 months later from cancer at age 55 on April 1954.

At the time (2020), it didn't occur to me to look into base rates (the Revolt of the Admirals and interservice conflict over nukes were clearly NOT base rates though). I also thought at the time that this was helpful to understand the modern US military, but I was wrong; WW2 was started with intent to kill, they thought diplomacy would inevitably fail for WW3 just like the last 2 world wars did, and they would carpet bomb Russia with nukes, like Berlin and Toyko were carpet bombed with conventional bombs.

Modern military norms very clearly have intent to maneuver around deterrence rather than intent to conquer, in large part because game theory wasn't discovered until the 50s. Governments and militaries are now OOD in plenty of other major ways as well.

This doesn't seem like it actually has anything to do with the topic of the OP, unless you're proposing that the US military used nuclear weapons on each other. Your second paragraph is even less relevant it's about something you claim to be a transfomative technological advance but is not generally considered by other people to be one, and it doesn't describe any actual transformation it has brought about but merely conjectures that some people in a government agency might not have figured it out yet.

I do not think that trying to wedge your theories into places where they don't really fit will make them more likely to find agreement.

During the start of the Cold War, the incumbents in the US Navy ended up marginalized and losing their status within the military, resulting in the Revolt of the Admirals. The Navy was pursuing naval-based nuclear weapons implementations in order to remain relevant in the new nuclear weapon paradigm due to their long-standing rivalry with the Army, but the plan was rejected by the central leadership due to lacking enough strategic value relative to the cost. As a result, the incumbents lost out; Roko explicitly referred to incumbents facing internal conflict: "European aristocracy would rather firearms had never been invented."

Regarding human thought/behavior prediction/steering, my thinking is that Lesswrong was ahead of the curve on Crypto, AI, and Covid by seriously evaluating change based on math rather than deferring to prevailing wisdom. In the case of 2020s AI influence technologies, intense impression-hacking capabilities are probably easy for large companies and agencies to notice and acquire, so long as they have large secure datasets, and the math behind this is solid e.g. tracking large networks of belief causality, and modern governments and militaries are highly predisposed to investing in influence systems.

If I've committed a faux pass or left a bad impression, then of course that's a separate matter and I'm open to constructive criticism on that. If I'm unknowingly hemorrhaging reputation points left and right then that will naturally cause serious problems.

Roko's post is not about the general problem of incumbents facing internal conflict (which happens all the time for many reasons) but about a specific class of situation where something is ripe to be taken over by a person or group with new capabilities, and those capabilities come along and it happens.

While nuclear weapons represented a dramatic gain in capabilities for the United States, what you're talking about isn't the US using its new nuclear capabilities to overturn the world order, but internal politicking within the US military. The arrival of nuclear weapons didn't represent an unprecedented gain in politicking capabilities for one set of US military officials over another. It is not helpful to think about the "revolt of the admirals" in terms of a "(US military officials who could lose influence if a new kind of weapon comes along) overhang", so far as I can tell. There's no analogy here, just two situations that happen to be describable using the words "incumbents" and "new capabilities".

My thinking on your theories about psychological manipulation is that they don't belong in this thread, and I will not be drawn into an attempt to make this thread be about them. You've already made four posts about them in the last ~2 weeks and those are perfectly good places for that discussion.

In this 11-paragraph post, the last two paragraphs turn the focus to incumbents, so I thought that expanding the topic on incumbents was reasonable, especially because nuclear weapons history is highly relevant to the overall theme, and the Revolt of the Admirals was both 1) incumbent-focused, and 2) an interesting fact about the emergence of the nuclear weapons paradigm that few people are aware of.

My thinking on the current situation with AI-powered supermanipulation is that it's highly relevant to AI safety because it's reasonably likely to end up in a world that's hostile to the AI safety community, and it's also an excellent and relevant example of technological overhang. Anyone with a SWE background can, if they look, immediately verify that SOTA systems are orders of magnitude more powerful than needed to automatically and continuously track and research deep structures like belief causality, and I'm arguing that things like social media scrolling data are the main bottleneck for intense manipulation capabilities, strongly indicating that they are already prevalent and therefore relevant.

I haven't been using Lesswrong for a seventh of the amount of time that you have, so I don't know what kinds of bizarre pretenders and galaxy-brained social status grabs have happened over the years. But I still think that talking about technological change, and sorting bad technological forecasts from good forecasts, is a high-value activity that LW has prioritized and gotten good at but can also do better.

Imagine an almost infinite, nearly flat plain of early medieval farming villages populated by humans and their livestock (cows, horses, sheep, etc) politically organized into small duchies and generally peaceful apart from rare skirmishes.

Add a few key technologies like stirrups and compound bows (as well as some social technology - the desire for conquest, maneuver warfare, multiculturalism) and a great khan or warlord can take men and horses and conquer the entire world. The Golden Horde did this to Eurasia in the 1200s.

An overhang in the sense I am using here means a buildup of some resource (like people, horses and land) that builds up far in excess of what some new consuming process needs, and the consuming process proceeds rapidly like a mountaineer falling off an overhanging cliff, as opposed to merely rolling down a steep slope.

The Eurasian Plain pre-1200 was in a "steppe-horde-vulnerable-land Overhang". They didn't know it, but their world was in a metastable state which could rapidly turn into a new, more "energetically favored" state where they had been slaughtered or enslaved by The Mongols.

Before the spread of homo sapiens, the vertebrate land animal biomass was almost entirely not from genus homo. Today, humans and our farm animals comprise something like 90% of it. The pre-homo-sapiens world had a "non-civilized-biomass overhang": there were lots of animals and ecosystems, but they were all pointless (no globally directed utilization of resources, everything was just a localized struggle for survival, so a somewhat coordinated and capable group could just take everything).

Why do these metastable transitions happen? Why didn't the Eurasian Plain just gradually develop horse archers everywhere at once, such that the incumbent groups were not really disrupted? Why don't forests just gradually burn a little bit all over the place, so that there's never a large and dangerous forest fire? Why didn't all animal species develop civilization at the same time as humans, so that the human-caused extinction and extermination of most other species didn't happen?

It's because the jump from the less-favored to the more-favored state in a technological transition is complex and requires nontrivial adaptations which other groups would perhaps never develop, or would develop much more slowly. Dolphins can't make a civilization because they don't have access to hands or fire, so they are basically guaranteed to lose the race for civilization to humans. Mongols happened to get all the ingredients for a steppe empire together - perhaps it could have been someone else, but the Mongols did it first and their lead in that world became unstoppable and they conquered almost everything on the continent.

These transitions can also have threshold effects. A single burning leaf might be extinguished and that's the end of the fire. A single man with stirrups and a bow is a curiosity, ten thousand of them are a minor horde that can potentially grow. So the new state must cross a certain size threshold in order to spread.

Threshold scale effects, spatial domino effects and minimum useful complexity for innovations mean that changes in the best available technology can be disruptive overhang events, where some parameter is pushed much further than its equilibrium value before a change happens, and the resulting change is violent.

As well as being fast/violent/disruptive, these changes tend to not be good for incumbents. Eurasian farmers would rather the Mongol empire hadn't come into existence. European aristocracy would rather firearms had never been invented. But they also tend to be very hard to coordinate against once they get going, and it's hard to persuade people that they are real before they get going.

Of course there is some degree of change where a gradual transition is favored over a violent phase change. A slightly innovative military weapon may simply get shared around the world, rather than giving the entity that invented it enough of an advantage to roll everyone else up. If you are an incumbent and you have any choice in the matter, you would almost certainly prefer that the rate of change is below the threshold for violent, overhang-y metastable transitions.