It's been a while since I looked into Stampi, but from what I remember Claudio Stampi optimizes for the performance during a race and makes statements about what's optimal for the race environment. As far as I remember Stampi does not advocate that the sailors go down to those low amounts of sleep outside of their racing conditions. In most sports, the behavior that's optimal for maximum sports performance is not the behavior that's optimal for long-term health.

I'm unsure what to make of your main points.

Your description of sleep 10,000+ years ago is a bit misleading. My backpacking experience tells me that it doesn't take too long to learn to sleep comfortably on unpadded ground. It doesn't take modern technology to deal with cold well enough to sleep comfortably - I suspect modern people have more trouble, because they keep their bedrooms at daytime temperatures (i.e. too warm).

If it was harder to sleep in the past, it's primarily because of dangers. I presume this was quite variable. This article on ancestral sleeping postures mentions constraints on sleep posture due to insects, lions, and human enemies. The larger threats seem to be handled by having someone awake at any given time. Crawling insects were handled via grass beds. I'm puzzled as to how flying insects impacted sleep. I've had problems with them while sleeping outdoors, but I think they mostly go away in the middle of the night?

I wrote large chunks of this essay having slept less than 1.5 hours over a period of 38 hours. I came up with and developed the biggest arguments of it when I slept an average of 5 hours 39 minutes per day over the preceding 14 days. At this point, I’m pretty sure that the entire “not sleeping ‘enough’ makes you stupid” is a 100% psyop. It makes you somewhat more sleepy, yes. More stupid, no. I literally did an experiment in which I tried to find changes in my cognitive ability after sleeping 4 hours a day for 12-14 days, I couldn’t find any. My friends who I was talking to a lot during the experiment simply didn’t notice anything.

I find it implausible that your anecdotes and a non-RCT N=1 self-experiment provide stronger evidence than several N≈20 non-pre-registered RCTs.

Yes, p-hacking and lack of pre-registration are bad, but IMO those things are pretty much negligible concerns when studies test cognition with several tests and find the same effect on almost all of them.

When I read the literature on the cognitive effects of sleep deprivation, it doesn't sound like experimenters are giving subjects several tests, finding no effect on most of them, and then focusing on ...

I want to emphasize that I agree that we ought to prefer study data to N=1 motivated self-experiment, and I appreciate you bringing this meta-analysis to the table.

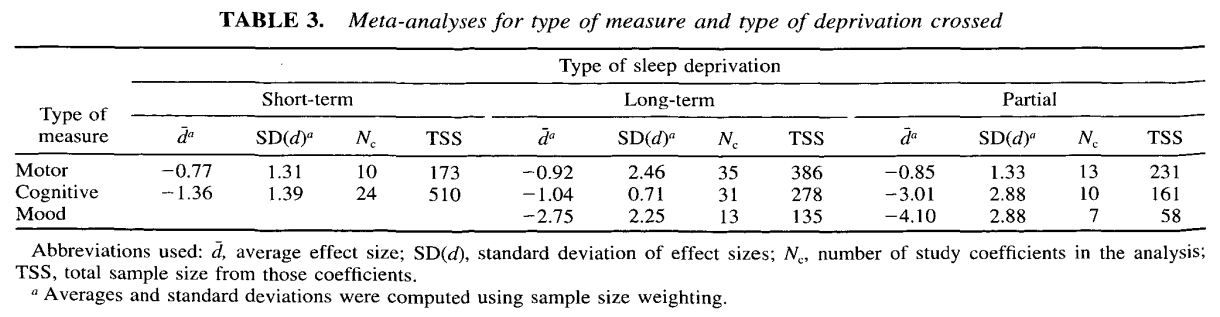

Now, let's take a close look at Pilcher and Huffcutt.

Guzey's self-administered study would be coded by P&H as "partial sleep deprivation" (< 5 hours sleep in a 24 hour period), the group showing the largest negative effect sizes in P&H. Note, however, that P&H are aggregating results from just 6 studies (citation numbers 39-41,44,48,49).

The experimental groups of these 6 studies included:

- Anesthesia residents after 24 hours of in-house call.

- Medical interns at work.

- Periodic testing of graduate students at a psychological research center over 8 months, while the students lived an otherwise normal life.

- Soldiers on an 8-day field artillery trial manually handling a large quantity of artillery shells (weighing 45 kg) and charges (13 kg).

- Surgical resident's who've been up working all night.

- Internal medicine residents after a night on call.

In all but the trial on the graduate students, the subjects were dealing with both sleep deprivation and work-related fatigue. Guzey's specifically interested in sleep deprivati...

I did a little epistemic spot checking:

- Read the memory consolidation review article

- Browsed two pages of Googe Scholar abstracts for the search "cancer risk sleep duration"

- Looked at the abstract of the epidemiological study Guzey cites against the cancer/sleep deprivation

- Googled for "world health organisation sleep epidemic"

So far, all of Guzey's specific claims about incorrect statements by Walker have held up. That epidemiological study on sleep duration and cancer risk? Not cherry-picked. If you look at the other two pages of cancer risk/sleep duration studies, hazard ratios are typically small (though one is around 1.6, IIRC). Some show elevated cancer risk for longer-duration sleep (on the order of 10 hours). Most show little-no effect, though some that show no effect in aggregate find subgroup effects.

I feel unbelievably stupid saying this, but the format of Guzey's takedown post, and this post even moreso, have a style and format that makes me particularly nervous. Maybe it's the font. If I bought the argument, then I might want to show it to other people, who'd see a very long and strongly worded blog post with LOTS OF BOLD AND UNDERLINE with Twitter inclusions totally takin...

lmao I started reading this comment and was like "oh no i'm about to be destroyed" and instead everything held up 😎

I guess showing drafts to literal dozens of people before publishing actually works haha.

Here's one way of thinking about sleep which seems compatible with both the less-sleep-needed thesis and the lower-productivity-while-deprived observation: Some minimal amount of sleep provides a metabolic / cognitive role, and beyond this amount, additional hours of sleep were useful in the evolutionary context to save calories when the additional wakeful hours would not provide pay off.

If true, we'd expect there to a more-or-less fixed function from sleep quantity to sleepiness within the very low sleep range, but in the mid-sleep (5-8 hr?) range this function from quantity to sleepiness would be entirely mediated by stimulation. Stimulation here could mean physical exercise, but I expect excitement / anticipation are also very relevant -- in an evolutionary context such feelings signal higher payoff for wakefulness.

The importance of such a perspective, is that reducing sleep quantity would be possible only conditional on the upstream stimulation/excitement variable. Elon, Guzey, highly motivated or active people would all have an easier time avoiding unpleasant struggles to overcome sleepiness. If you are not highly motivated / excited by a given day's activities there are a few...

I'm not sold on the conclusions right now but I think this raises a number of excellent points (particularly the analogy with fasting) and I'm really looking forward to an extended discussion of it.

The fasting analogy is interesting, as is the analogy with exercise -- some kinds of activities are beneficial in the long-run even when they are damaging/unpleasant in the short run. But surely these are exceptions to the general rule, right?

- Besides exercise, it's not good to repeatedly injure yourself and then have the wounds heal. (Exercise is essentially the small, specific subtype of "injury" which is actually good for the body in the long term.)

- Getting sick with a cold or flu is good at building immunity to that kind of virus when it comes around a second time, but aside from immunity concerns, it would be better for your health to never become sick at all. (As with viruses, the same goes for diseases caused by parasites or bacteria.) Especially as a young child, getting badly sick can impact your development and later IQ / income / etc substantially. Getting mildly sick is probably mildly bad for those same metrics.

- On the other hand, I enjoyed your post a few months ago examining whether letting kids play outside and get dirty is helpful for calibrating their immune systems and reducing allergies later in life. It seems like the "hygiene h

I am much more sold on "variety is good for humans, and mild-moderate deprivation and excess is variety" than "humans should permanently run on much less sleep than they think they need" or "sleepiness is a lie".

One tricky thing here is humans aren't actually guaranteed to have a pareto optimim, or to have a path that gets all good things. It seems really plausible childhood illnesses damages development and IQ, and lack of childhood illness causes allergies and immune vulnerability later (I think think the hygiene/old friends hypothesis is largely correct, even if it doesn't support eating dirt in particular), and there isn't an ideal level that gets you your max IQ and no allergies. Variety is something of a hack to get some of both and also create a discovery process for what you need more at a particular moment.

Curation notice: I'm far from sold on the specific conclusions of this piece (discussed more here, EDIT: and by AllAmericanBreakfast below), but I'm really excited to see the combination of strongly grounded criticisms of existing work, new hypotheses, and serious experimentation to test those hypotheses. In my ideal world this leads to more people running experiments that produce useful object-level data and a better approach for those experiments, which can be scaled (e.g. how do you measure cognitive abilities over a year, reliably and with minimal time costs), and eventually leads to a better understanding of sleep and how a given person should optimize for their goals.

I see some basic flaws in the sleep-exercise and sleep-food analogies.

There are reasonably well-understood physiological mechanisms showing how slight overuse of muscles starts a process of strengthening those muscles. I did not see any proposed mechanism for less sleep reducing your need for sleep. (If I missed it, please let me know). While it is true of lots of inputs (food, oxygen) I do not think it is defensible to arbitrarily generalize the idea that reduction of any input allows you to function with less of that input.

With the food analogy specifically, there is a much different element of control. I can sit in front of a delicious meal at any time and abstain, even if my body is "telling" me I am starving, or I can eat garbage if my body is "telling me" I am not hungry. I can't do that with sleep without chemical help, except perhaps delay sleeping for a few hours or sleep a few hours late. My conclusion is that I sleep when my body needs sleep. If I go to bed and 9 hours later wake up naturally, I needed the 9 hours.

Of course, if I wake up and have nothing to do, and decide to stay in bed for another hour, that does not mean my body needed 10 hours. But the 9 hours I had no conscious control over? Yup, my body did what it needed to do.

Guzey substantially retracted this a year later. I think it would be great to publish both together as a case study of self-experimentation, but would be against publishing this on its own.

...Get minimum possible sustainable amount of sleep -> get enough sleep to have maximum energy during the day

Sleep makes me angry. I mean, why on Earth do I have to spend hours every day lying around unconscious?????????

In 2019, trying to learn about the science behind sleep I read Why We Sleep and got so angry at it for being essentially pseudoscience that I spent >100 hours debunking it. In 2020, I slept 4 h/day for 2 weeks and shown that this didn’t make me dumber (not recommended, it was terrible). In 2022, I published Theses on Sleep, with points like “Experiencing sleepiness is normal and does not necessarily imply that you are undersleeping. Never being sleepy means you are probably sleeping too much.”

What I changed my mind about

1. There’s no good medical reason to sleep more than the minimum you can sustain.

Not this one! Fight me.

2. I can sleep 4h/day, so 6h/day must be easy.

It turns out that sleeping 6h/day is hard… I have to track sleep & adjust for every party I go to, dea

This post is very interesting and I'm excited to hear back from anyone who is going to experiment based on it. My experience with sleep deprivation is mostly centered around having children; my functioning is unquestionably impacted by that kind of fragmented and reduced sleep (especially emotionally) but maybe a solid yet shorter period of sleep would actually be fine. The trouble is I'm not sure how I'd check... because I've found that if I have an alarm set to go off in the morning, not only is it in itself staggeringly unpleasant, it makes me anxious enough that I sleep very poorly the night before. I've gone to a lot of effort to (kids and all) arrange that I can sleep in as late as feels right.

I had sleep problems all my adult life, which I eventually found were due to sleeping too much (or more accurately, thinking I should get 8 hours' sleep, and thus allowing too much time to sleep in).

I conducted an experiment on myself over several months using 21 different factors claimed by the literature to affect sleep. None of them helped. (Though a few of the factors I was doing anyway, e.g. having a comfortable mattress & pillow, so weren't worth varying; and several made sleep worse for obvious reasons, e.g. stress & illness, but weren't things I could actively improve.)

However, I then tried a (very good) online sleep course at www.sleepio.com, which among other things got me to try various adjustments to my sleep hours. This revealed something I hadn't considered - viz. I'd always assumed I should ideally be getting 8 hours' sleep. So I was allowing too much time to sleep in, producing shallow sleep, and waking up often in the night. The web site made me gradually shrink my sleep time so I slept shorter but deeper, until I stopped waking up in the night. It also helped by making me establish a regular wake time.

As a result, I went from getting a full night's sleep just once a year, to almost every night. And also wasted less time in bed, either lying awake or snoozing.

I did a talk about all this, which is here. E.g. it goes through the 21 factors, which people may find useful.

I'm a tutor, and I've noticed that when students get less sleep they make many more minor mistakes (like dropping a negative sign) and don't learn as well. This effect is strong enough that for a couple of students I started guessing how much sleep they got the last couple days at the end of sessions, asked them, and was almost always right. Also, I've tried at one point going on a significantly reduced sleep schedule with a consistent wakeup time, and effectiveness collapsed. I soon burned out and had to spend most of a day napping to catch up on sleep.

At this point I do think enough sleep is important, and have a different hypothesis that needed sleep is just different for different people.

Extremely interesting article with a number of good points!

Is there any chance that you could expand upon the driving objection? Why, in your model of sleep and the cognitive effects of sleep, does getting little sleep increase your risk of getting into a car accident when driving?

Another point: I find Mendelian randomization studies fairly convincing for the long-term effects of sleep. For example, here's one based on UK Biobank data suggesting that sleep traits do not have an interaction with Alzheimer's disease risk: https://academic.oup.com/ije/article/50/3/817/5956327

Hello Guzey! Your blog and your new organization are a big inspiration to me. I greatly enjoyed this post; here is a grab-bag of thoughts which hopefully contains some useful info for you:

- You might be interested to learn that some corners of Buddhism sometimes seem to have a strong anti-sleepiness agenda:

- The Buddha himself warned against sleeping in excessively luxurious beds -- it is the last of a series of eight moral commandments that good monks should uphold. But it's unclear if this teaching was intended to prevent people from oversleeping, or to prevent them from flaunting their wealth and status, or some other purpose like discouraging sexuality.

- Besides metaphorical "awakening", Buddhism places lots of emphasis on literal wakefulness including a long litany of tips on avoiding laziness in general and drowsiness during meditation in particular.

- Finally and most intriguingly, there is a long tradition of claims that advanced meditators need less sleep, presumably because time spent meditating is making up for the need for sleep.

- How are you measuring sleep hours? Are you talking about time in bed or time asleep as measured by a device like a fitbit?

In contrast, today: you sleep on your super-comfortable machine-crafted foam of the exact right firmness for you.

It sounds to me like you are saying that while the field of sleep science is quite shitty, the field of mattress design is very good.

As a Westerner who's used to sleeping on a soft mattress sleeping on a hard floor is very uncomfortable but it's my impression that it feels better for people who aren't adapted to sleeping on mattresses.

If I have body awareness (my attention is not filled up with other things) I can relax better sitting on a hard floor than sitting on a soft couch.

On the analogy with fasting,

Even if sleep works the way you suppose, this analogy looks like apples and oranges, so I don't like it.

With fasting, you can infer that it's harmless just by knowing that (1) the average lean human has fat reserves to last three months, (2) total fasters don't go through some calamity like losing lots of muscle protein (if they did, there'd be unambiguous results everyone knew) and (3) in the EEA it was probably common to have periods of scarcity such that you go several days without finding food. In other words, fasting was ab...

I am two people removed away from a gentleman who has a sleep disorder that means he can never sleep more than two hours, and he's otherwise healthy. That seems to suggest if there are negative effects from lack of sleep, they aren't incurred from practical biological necessity, but from what our brains do to enforce sleep.

Also, OP, if you actually don't have any ill effects from 6 or so hours of sleep, it's possible you might have a similar genetic condition.

In the comments, I don't understand why people seem to be so swayed by the comparison of sleep dep...

I’m pretty sure that the entire “not sleeping ‘enough’ makes you stupid” is a 100% psyop

Why would it be a psyop? By who and with what motivation/intention?

I heavily sympathize with a lot of the views from this post.

I used to sleep much more (~9 hours), but as I've aged, I now tend to sleep between 3-5 hours a night. This was a rather conscious choice on my part, but now I find it hard to revert to my previous behavior. I switched to various forms of polyphasic sleep during my bender through academia from 2004-2006, and while I eventually abandoned polyphasic, I haven't switched gone back to a "regular" sleep schedule since.

I do find that at my most acute stage of sleep deprivation I become much more mo...

I started walking in the morning (within an hour of waking, though supposedly within thirty minutes is even better, don't know evidential base) and found myself sleeping less and waking earlier more consistently and feeling tired around the same time more consistently. From ~averaging 8.5 down to 7.5. Sometimes I wake really early, around sunrise, and find myself wanting a nap in early evening. This was very notable for me after decades of sleep problems and hating hating hating sleep interventions.

This is super interesting, thanks! I'm almost embarrassed that it never occurred to me to question some of these things. Like Elizabeth, I'm not totally sold on all the conclusions right now, but it's still interesting to think about.

Personal reflection / anecdotal evidence: There are two time periods (~9-12 months each) that I look back on as my happiest and most productive times. During both, I stuck to a strict 10pm–6am sleep schedule, and I felt great (I did sometimes nap if I felt I needed it, I think). However, when not on a strict schedule, I usuall...

Generally interesting, but I have a quibble with this:

In the text here, you say

>>Walker outright fakes data to support his “sleep epidemic” argument. The data on sleep duration Walker presents on the graph below simply does not exist:

I went to your link to see the proof that it does not exist. Pretty extraordinary claim. Difficult to prove a negative and all. Figured I would find something solid. Other than two studies with evidence that contradicts Walker's general claim with a few specific examples, here's what you had:

>&...

You can check this out for yourself. Search PubMed or Google Scholar for "sleep deprivation cancer risk." Plenty of studies come up, but the vast majority find little-no link. The biggest hazard ratio I could find was 1.6, which is not a doubled cancer risk. Note also that Walker has actually retracted his "WHO has declared a sleep epidemic claim," so we have a concrete example of the guy making stuff up.

There's a lot of interesting stuff in the post, but the following counter-point you offer to "the idea that sleep’s purpose is metabolite clearance" I can't quite follow:

...The paper is called “Sleep Drives Metabolite Clearance from the Adult Brain”. The abstract says:

The conservation of sleep across all animal species suggests that sleep serves a vital function. We here report that sleep has a critical function in ensuring metabolic homeostasis. Using real-time assessments of tetramethylammonium diffusion and two-photon imaging in live mice, we show that nat

Sleep Disturbance, Sleep Duration, and Inflammation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies and Experimental Sleep Deprivation (schi-hub link).

Here's the #1 link on Google Scholar that comes up on a search for "inflammation sleep deprivation" (> 800 citations).

They're looking at inflammatory cytokine levels (CRP, IL-6, and TNF-a), which I can confirm (biomedical engineering MS student currently studying immunology) are key drivers of the inflammatory response, though the immune system is a complex interconnected pathway without a straightforward protein "gas pedal." Here's my quick interpretation of the abstract in terms of the support it lends for the sleep deprivation/inflammation connection.

Pros:

- n > 50,000, no evidence of publication bias

- Found sleep disturbance (poor sleep, sleep complaints) associated with CRP and IL-6, and shorter sleep duration (< 7 hours/night) with CRP.

- The researchers do note in the last sentence findings from another study that "Indeed, treatment of insomnia has been found to reduce inflammation and together with diet and physical activity represents a third component in the promotion of sleep health." The insomnia treatments in t

One of the things that I am really worried about is Alzheimer's. Even a slight risk of Alzheimer's would be enough to convince me to sleep more. Alzheimer's is significantly caused by UPDATE: correlated with the buildup of plaques in the brain, and the process of cleaning that away seems to be tied to sleep or at least the circadian rhythm - which I guess can be disrupted in many ways.

Recent study:

https://journals.plos.org/plosgenetics/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgen.1009994

I can anecdotally report that when I started consistently getting up immediately upon my alarm going off the subjective feeling of the first 5-10 minutes was far superior and I didn't feel much tiredness even with a relatively short night of sleep. I started doing this through setting my alarm to the maximum latest time possible and still allow me to get to work on time, and then noticed how much better I felt while doing this (previously I was a chronic snooze-button masher and felt pretty groggy waking up).

I have noticed in the WFH/office phases of the p...

Unlike the other commentors, I am sold enough on the conclusion to give it a try.

I've been waking up at the same time every day (~95% of the time) and sleeping at roughly the same time every night (~70% of the time). What I'll do is keep waking up at the same time but just go to bed when I'm tired instead of ~8 hours before my waking time.

I don't have any issues with tiredness/low-energy. Ideally that would continue and I would be able to reclaim an hour or two from each day.

I used to use a Fitbit to track my sleep. I noticed that after sleeping very few hours, I'd have more % deep and REM sleep the following night (and less % light sleep / restlessness) often enough for me to notice a correlation. I checked my friend's Garmin sleep stats and it's roughly the same.

I wouldn't give too much weight to the accuracy of this observation (confounding, device accuracy etc). However it just about makes the cut to share it in a comment imo.

One point that I would like to see discussed is the relation between lack of sleep and allergies. In general, I have some minor dust allergy. However, when I'm sleep deprived and something triggers my allergy, the symptoms (sneezing, nose running, red eyes...) are several orders of magnitude stronger and really impede normal life. The effect is cumulative, I mean that this happens only when I haven't slept enough for several days. I take it as something valuable, as it is a reliable sign for me that I need to rest.

I have once quickly searched a bit the sci...

I'd be interested on your thoughts on baby blues. That women tend to get depressed in the most sleep-deprived time of their lives does seem very contradictory with what you expose. (I know, hormones; but still, strange timing). I guess one could argue that without the effects mentioned in the post, it would be all the women that would suffer baby blues. Is there any research on this?

I'm very interested in the idea that most of the negative recorded effects of sleep deprivation are caused by sleepiness, not sleeplessness. However, there are some effects that you cannot attribute to sleepiness, like hormonal changes.

I would love to see more research done, but I think I've decided epistemically that I have to trust the body of knowledge before I trust somebody on the internet. It seems like you're alleging an entire conspiracy in sleep science, and your evidence is not good enough to brook that.

In addition, using evidence like a sl...

One of Guzey's projects is to advance his own claims about how sleep works, and I agree that his data is on the bottom of the epistemic pyramid. His other project, though, is a critique of the interpretation of sleep research data, and here he is on firmer ground.

You can check out my comment above showing that investigating a meta-study of sleep research on the type of sleep deprivation Guzey's mainly focused on (i.e. a consistent 5.5 hours or of sleep so per night) shows that the meta-study is profoundly flawed. You can check it out for yourself - that's how science is supposed to work!

In addition, using evidence like a sleep scientist falsifying data once to write a book does not actually help your case.

I think you should split up your assertions about Guzey's speculations about how sleep works, his criticism of sleep studies, and his assertions about the state of the field.

Let's say that the field really was in a poor state, with a heavy admixture of poor studies, misleading analysis, and various intensities of misrepresentation up to and including outright fraud. We've seen this phenomenon in other scientific fields. Our priors ought to be low, perhaps, but it's not impossible ...

in no way am trying to make people think that the analogies that I thought of that I find convincing should be convincing to other people.

This reads as a denial of persuasive intent, which is clearly not the case.

Your post consists of more than analogies that you thought of. It also consists of data, your own self-experiments, arguments, citations, critiques of the literature and of Matthew Walker's book. It doesn't need to make us convinced of the truth of all your beliefs re: sleep to be a piece of writing with persuasive goals. I posit that virtually anybody who reads either this or your original piece on Walker's book would find them clear examples of scientific writing that's aiming to persuade the reader.

I happen to find your work pretty interesting, something I've already spent a lot of time investigating here in the comment section. It's the kind of information I'd want to share and explore with other people. As you were the one who brought it to my attention, I'd like to be able to use you and your writing as a reference when I do so.

However, I have to consider what the reaction of the person I shared it with might be if I did so.

Knowing the typical reactions of people who...

appears clearly to be just a thought experiment to me.

The point isn't what you intended to come across in your writing, but what actually does come across in your writing, and the expectations that creates in the reader about how others will perceive your writing.

By analogy, let's say you go to a party and tell a joke making fun of my friend Sarah's shoes. You think it's funny and mean it as a bit of friendly teasing. I know that you're a little nervous and are just trying to connect, and the joke honestly seems kind of funny to me.

However, I also know Sarah's sensitive about her shoes, and that the others who heard the joke probably hear it as mean-spirited, because they don't know you very well. Plus, the joke really did feel mean to me, even though I also found it humorous at the same time.

Because of that, I feel pressure to reprimand you, and maybe not to bring you back to another party in the future. This is partly because I want to make Sarah feel defended, but also because I'm concerned that others will think I'm mean if I don't distance myself from you. They'll certainly think that if I then go around telling other people the joke.

It's this sort of reaction that the aspects...

I find myself agreeing with most of his premises. Except that sleep and memory arent really linked. From experience as a pianist, one can play a difficult passage on the keyboard and get stuck one day one, stop to sleep, and on day two have an accelerated mastery that wasnt present at the end of day one. it's integration of these actions/skills specifically during sleep and probably dreams, so it is muscle memory, somewhat unconscious, yet still a kind of memory, yes? I swear by the truth of this, from personal experience.

Additionally, having been depres...

This is FASCINATING. I sleep a natural 9 hours per night and still often feel quite tired throughout the day. (Setting up a sleep study with doctors this month but I barely snore, so doubt it’s apnea). The idea that I could maybe do just as well on 7 hours or less is very exciting and I’ll be trying it right away. I have a lot of problems with mental tiredness lasting throughout the day; I have been thinking about my sleep a lot lately and have noticed that even when I do rarely sleep 6 hours or so, my mind can still be awake even while my body feels tired...

Thanks for this post. To clarify, it sounds like your thesis is about duration of sleep, not quality of sleep? How's the evidence for sleep quality and life outcomes? (And what interventions improve it?)

So, most people see sleep as something that's obviously beneficial, but this post was great at sparking conversation about this topic, and questioning that assumption about whether sleep is good. It's well-researched and addresses many of the pro-sleep studies and points regarding the issue.

I'll like to see people do more studies on the effects of low sleep on other diseases or activities. There's many good objections in the comments, such as increased risk of Alzheimer's, driving while sleepy and how the analogy of sleep deprivation to fasting may b...

noting that sleeping 1.5 hours per day less results in gaining more than a month of wakefulness per year, every year.

This is wrong. 1.5 * 365 / 24 ~ 22.8 days. I think this comes from the 33 days of life every year statistic later on, which is based on sleeping 2 hours less per day.

Re sleep deprivation inducing mania, I sometimes fast (either on 100kcal or 700kcal per day for 5-6 days), and find (as others do) that after a day or so I go into a hyperactive state - very alert, clear-minded, energetic, probably not far from mild mania. (And unlike as described in the OP, I don't get hungry at all - or rather, only did the first couple of times I fasted. So it presumably it just takes getting used to.)

So I wonder if the analogies between sleep and eating are even closer than suggested.

Re the analogy with fasting, more broadly this would be an example of hormesis, i.e. the principle that many sources of stress are beneficial in small quantities. (As others mentioned, though they didn't use the general term.) Other examples include:

- mild toxins, such as spices and bitter flavours (thought to be the evolutionary reason we like them, if in small quantities)

- heat & cold, e.g. saunas and cold showers

- mild diseases - hence vaccines

- radiation, which curiously seems to reduce cancer risk in low doses.

Sleep deprivation may be somewhat different a...

Very very nicely written. As someone who suffers from sleep apnea and is incredibly curious about sleep this was a fantastic read. I would say one thing I am not sure you pointed out because I skimmed the apendix part is sleep quality. If you have poor sleep quality you will sleep more and feel tired, thinking you need more sleep. If you have good sleep quality you can get by with less sleep or more variance in your schedule. If you have sleep apnea you are looking at heart disease -> death if you don't sort out your sleep hygeine.

I'm curious to learn more about the thesis that caffeine or other stimulant use can completely mitigate the effects of sleep deprivation until 30+ hours without sleep. My own (subjective, anecdotal) experience with caffeine is that occasional (once or twice a week) caffeine use fairly effectively mitigates occasional sleep deprivation if I got say 5-6 hours of sleep the night before as opposed to my preferred 7-8, but is not too effective if I slept less than 4 hours the night before. The more often I use caffeine, the less effective the caffeine bec...

Published originally (with all of the footnotes) on my site: https://guzey.com/theses-on-sleep/

Summary: In this essay, I question some of the consensus beliefs about sleep, such as the need for at least 7 hours of sleep for adults, harmfulness of acute sleep deprivation, and harmfulness of long-term sleep deprivation and our inability to adapt to it.

It appears that the evidence for all of these beliefs is much weaker than sleep scientists and public health experts want us to believe. In particular, I conclude that it’s plausible that at least acute sleep deprivation is not only not harmful but beneficial in some contexts and that it’s that we are able to adapt to long-term sleep deprivation.

I also discuss the bidirectional relationship of sleep and mania/depression and the costs of unnecessary sleep, noting that sleeping 1.5 hours per day less results in gaining more than a month of wakefulness per year, every year.

Note: I sleep the normal 7-9 hours if I don’t restrict my sleep. However, stimulants like coffee, modafinil, and adderall seem to have much smaller effect on my cognition than on cognition of most people I know. My brain in general, as you might guess from reading my site, is not very normal. So, be cautious before trying anything with your sleep on the basis of the arguments I lay out below. Specifically do not make any drastic changes to your sleep schedule on the basis of reading this essay and, if you want to experiment with sleep, do it gradually (i.e. varying the average amount of sleep by no more than 30 minutes at a time) and carefully.

Comfortable modern sleep is an unnatural superstimulus. Sleepiness, just like hunger, is normal.

The default argument for sleeping 7-9 hours a night is that this is the amount of sleep most of us get “naturally” when we sleep without using alarms. In this section, I argue against this line of reasoning, using the following analogy:

Most of us (myself included) eat a lot of junk food and candy if we don’t restrict ourselves. Does this mean that lots of junk food and candy is the “natural” or the “optimal” amount for health?

Obviously, no. Modern junk food and candy are unnatural superstimuli, much tastier and much more abundant than any natural food, so they end up overwhelming our brains with pleasure, especially given that we are bored at work, college, or in high school so much of the day.

What if the only food available to you was junk food and candy?

Most of us (myself included) sleep 7-9 hours if we don’t have any alarms in the morning and if we get out of bed when we feel like it. Does this mean that 7-9 hours of sleep is the “natural” or the “optimal” amount?

My thesis is: obviously, no. Modern sleep, in its infinite comfort, is an unnatural superstimulus that overwhelms our brains with pleasure and comfort (note: I’m not saying that it’s bad, simply that being in bed today is much more pleasurable than being in “bed” in the past.)

Think about sleep 10,000 years ago. You sleep in a cave, in a hut, or under the sky, with predators and enemy tribes roaming around. You are on a wooden floor, on an animal’s skin, or on the ground. The temperature will probably drop 5-10°C overnight, meaning that if you were comfortable when you were falling asleep, you are going to be freezing when you wake up. Finally, there’s moon shining right at you and all kinds of sounds coming from the forest around you.

In contrast, today: you sleep on your super-comfortable machine-crafted foam of the exact right firmness for you. You are completely safe in your home, protected by thick walls and doors. Your room’s temperature stays roughly constant, ensuring that you stay warm and comfy throughout the night. Finally, you are in a light and sound-insulated environment of your house. And if there’s any kind of disturbance you have eye masks and earplugs.

Does this sound “natural”?

Now, what if the only sleep available to you was modern sleep?

Even if I convinced you about the “sleeping too much” part, you are still probably wondering: but what does depression have to do with anything? Isn’t sleeping a lot good for mental health? Well…

Depression <-> oversleeping. Mania <-> acute sleep deprivation

In this section, I argue that depression triggers/amplifies oversleeping while oversleeping triggers/amplifies depression. Similarly, mania triggers/amplifies acute sleep deprivation while acute sleep deprivation triggers/amplifies mania.

One of the most notable facts about sleep is just how interlinked excessive sleep is with depression and how interlinked sleep deprivation is with mania in bipolar people.

Someone in r/BipolarReddit asked: How many hours do you sleep when stable vs (hypo)manic? Depressed?

Here are all 8 answers that compare hours for manic and depressed states, note the consistency:

Low to Moderate depressed w/o mixed - 10 hours, if no alarm. With alarm less, but super hangover

Stable -Usually 7-9 hours

Hypomanic taking sedating evening meds - 5 to 7 hours

Hypomanic with no sedating evening meds - 3 to 5 hours

Manic out of hand - 0 to 3 hours

Manic in hospital put on maximum sedating meds or injections - 4 to 6 hours

Mixed episodes = same as hypo(manic)”

Lack of sleep is such a potent trigger for mania that acute sleep deprivation is literally used to treat depression. Aside from ketamine, not sleeping for a night is the only medicine we have to quickly – literally overnight – and reliably (in ~50% of patients) improve mood in depressed patients (until they go to bed, unless you keep advancing their sleep phase ). NOTE: DO NOT TRY THIS IF YOU ARE BIPOLAR, YOU MIGHT GET A MANIC EPISODE.

Figure 1. Copied from Wehr TA. Improvement of depression and triggering of mania by sleep deprivation. JAMA. 1992 Jan 22;267(4):548-51.

Why does the lack of sleep promote manic states while long sleep promotes depression? I don’t know. But here are a couple of pointers to interesting papers relevant to the question: Can non-REM sleep be depressogenic? Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is associated with synapse growth. Sleep deprivation appears to increase BDNF [and therefore neurogenesis?]. Papers that showed up when I googled “sleep deprivation bdnf”: The Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor: Missing Link Between Sleep Deprivation, Insomnia, and Depression. The link between sleep, stress and BDNF. BDNF: an indicator of insomnia?. Recovery Sleep Significantly Decreases BDNF In Major Depression Following Therapeutic Sleep Deprivation.

Jeremy Hadfield writes:

Occasional acute sleep deprivation is good for health and promotes more efficient sleep

In this section, I continue the analogy between eating and sleeping and extend it to exercise. I ask: if fasting and exercising are good, shouldn’t acute sleep deprivation also be good? And I conclude that it is probably good.

Let’s continue our analogy of sleep to eating and add exercise to the mix.

It seems to me that most common arguments against acute sleep deprivation equally “demonstrate” that fasting and exercise are bad.

For example, I ran 7 kilometers 2 days ago and my legs still hurt like hell and I can’t run at all. Does this mean that running is “bad”?

Well, consensus seems to be that dizziness, muscle damage (and thus pain) and decreased physical performance after the run, are not just not bad, but are in fact necessary for the organism to train to run faster or to run longer distances by increasing muscle mass, muscle efficiency, and lung capacity.

What about fasting? When I fast, I am more anxious, I think about food a lot, meaning that focus is more difficult, and I feel cold. And if I decided to fast too much, I would pass out and then die. Does this mean that fasting is “bad”? Well, consensus seems to be that occasional fasting actually activates some “good” kind of stress, promotes healthy autophagy, (obviously) helps to lose weight, etc. and is in fact good.

Now, what happens when I sleep for 2 hours instead of 7 one night? I feel somewhat tingly in my hands, my mood is heightened a little bit, and, if I start watching a movie with my wife at 6pm, I’ll fall asleep. Does this mean that sleeping 2 hours one night is bad for my health?

Obviously no. The only thing we observe is that my organism was subjected to acute stress. However, the reaction to acute stress does not tell us anything about the long-term effects of this kind of stress. As we know, both in running and in fasting, short-term acute stress response results in adaptation and in long-term increase in performance and in benefit to the organism.

I combed through a lot of sleep literature and I haven’t seen a single study that made a parallel to either fasting or exercise and I haven’t seen a single pre-registered RCT that tried to see what happens to someone if you subject them to 1-3 nights per week of acute sleep deprivation and allow to recover the rest of the nights. Do they perform better or worse in the long-term on cognitive tests? Do they have more or less inflammation? Do they need less recovery sleep over time?

I think that the answers are:

(The only parallel to fasting I’m aware of anyone making is by Nassim Taleb… when he was quote-tweeting me.)

Also see:

Our priors about sleep research should be weak

In this section, I note that most sleep research is extremely unreliable and we shouldn’t conclude much on the basis of it.

Do you believe in power-posing? In ego depletion? In hungry judges and brain training?

If the answer is no, then your priors for our knowledge about sleep should be weak because “sleep science” is mostly just rebranded cognitive psychology, with the vast majority of it being small-n, not pre-registered, p-hacked experiments.

I have been able to find exactly one pre-registered experiment of the impact of prolonged sleep deprivation on cognition. It was published by economists from Harvard and MIT in 2021 and its pre-registered analysis found null or negative effects of sleep on all primary outcomes (note that both the abstract and the main body of this paper report results without the multiple-hypothesis correction, in contradiction to the pre-registration plan of the study. The paper does not mention this change anywhere.).

So why has sleep research not been facing a severe replication crisis, similar to psychology?

First, compared to psychology, where you just have people fill out questionnaires, sleep research is slow, relatively expensive, and requires specialized equipment (e.g. EEG, actigraphs). So skeptical outsiders go for easier targets (like social psychology) while the insiders keep doing the same shoddy experiments because they need to keep their careers going somehow.

Second, imagine if sleep researchers had conclusively shown that sleep is not important for memory, health, etc. – would they get any funding? No. Their jobs are literally predicated on convincing the NIH and other grantmakers that sleep is important. As Patrick McKenzie notes, “If you want a problem solved make it someone’s project. If you want it managed make it someone’s job.”

Figure 2. Relative risk of showing benefit or harm of treatment by year of publication for large NHLBI trials on pharmaceutical and dietary supplement interventions. Copied from Kaplan RM, Irvin VL. Likelihood of null effects of large NHLBI clinical trials has increased over time. PloS one. 2015 Aug 5;10(8):e0132382.

Even in medicine, without pre-registered RCTs truth is extremely difficult to come by, with more than one half of high-impact cancer papers failing to be replicated, and with one half of RCTs without pre-registration of positive outcomes being spun by researchers as providing benefit when there’s none. And this is in medicine, which is infinitely more consequential and rigorous than psychology.

Also see: Appendix: I have no trust in sleep scientists.

Decreasing sleep by 1-2 hours a night in the long-term has no negative health effects

In this section, I outline several lines of evidence that bring me to the conclusion that decreasing sleep by 1-2 hours a night in the long-term has no negative health effects. To summarize:

In 2013, scientists tracked the sleep of 84 hunter-gatherers from 3 different tribes (each person’s sleep was measured for about a week but measurements for different groups were taken in different parts of the year). The average amount of sleep among these 84 people was 6.5 hours. Judging by CDC’s “7 hours or more” recommendation, 70% out of these 84 undersleep:

It appears that there is a distinct single-point mutation that allows some people to sleep several hours less than typical on average. A Rare Mutation of β1-Adrenergic Receptor Affects Sleep/Wake Behaviors:

The study compares carriers of the mutation in one family to non-carriers in the same family and finds that carriers sleep about 2 hours per day less. Given the complexity of sleep and the multitude of its functions, it seems extremely implausible that just one mutation in the β1-adrenergic receptor gene was able to increase its efficiency by about 25%. It seems that it just made carriers sleep less (due to more stimulation of a group of neurons in the brain responsible for sleep/wakefulness) without anything else obviously changing when compared to non-carriers.

A similar example of a drop in the amount of sleep required without negative side effects and driven by a single factor was described in Development of a Short Sleeper Phenotype after Third Ventriculostomy in a Patient with Ependymal Cysts. To sum up: a 59-year-old patient had chronic hydrocephalus. An endoscopic third ventriculostomy was performed on him. His sleep dropped from 7-8 hours a night to 4-5 hours a night without him becoming sleepy, he stopped being depressed, and his physical or cognitive performance stayed normal, as measured by the doctors.

Sleep is not required for memory consolidation. Jerome Siegel (the author of the hunter-gatherers study mentioned above) writes in Memory Consolidation Is Similar in Waking and Sleep:

The entire Scientific Consensus™ about sleep being essential for memory consolidation appears to be heavily flawed, driven by people like Matthew Walker, and making me lose the last remnants of trust in sleep science that I had.

Also see:

Conclusion

Ash Jogalekar

I’m not what they call a “natural short sleeper”. If I don’t restrict my sleep, I often sleep more than 8 hours and I still struggle with getting out of bed. I used to be really scared of not sleeping enough and almost never set the alarm for less than 7.5 hours after going to bed.

My sleep statistics tells me that I slept an average of 5:25 hours over the last 7 days, 5:49 hours over the last 30 days, and 5:57 over the last 180 days hours, meaning that I’m awake for 18 hours per day instead of 16.5 hours. I usually sleep 5.5-6 hours during the night and take a nap a few times a week when sleepy during the day.

This means that I’m gaining 33 days of life every year. 1 more year of life every 11 years. 5 more years of life every 55 years.

Why are people not all over this? Why is everyone in love with charlatans who say that sleeping 5 hours a night will double your risk of cancer, make you pre-diabetic, and cause Alzheimer’s, despite studies showing that people who sleep 5 hours have the same, if not lower, mortality than those who sleep 8 hours? Convincing a million 20-year-olds to sleep an unnecessary hour a day is equivalent, in terms of their hours of wakefulness, to killing 62,500 of them.

I wrote large chunks of this essay having slept less than 1.5 hours over a period of 38 hours. I came up with and developed the biggest arguments of it when I slept an average of 5 hours 39 minutes per day over the preceding 14 days. At this point, I’m pretty sure that the entire “not sleeping ‘enough’ makes you stupid” is a 100% psyop. It makes you somewhat more sleepy, yes. More stupid, no. I literally did an experiment in which I tried to find changes in my cognitive ability after sleeping 4 hours a day for 12-14 days, I couldn’t find any. My friends who I was talking to a lot during the experiment simply didn’t notice anything.

What do I lose due to sleeping 1.5 hours a day less? I’m somewhat more sleepy every day and staying awake during boring calls is even more difficult now. There’s no guarantee that what I’m doing is healthy after all, although, as I explained above, I think that it’s extremely unlikely due to likely adaptation, and likely beneficial effects of sleep deprivation (e.g. increased BDNF, less susceptibility to depression), and since I take a 20-minute nap under my wife’s watch whenever I don’t feel good.

An internationally known expert on acute sleep deprivation Dr. ALIEN SOLDIER (twitter account deleted).

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank (in reverse alphabetic order): Misha Yagudin, Bart Sturm, Ulysse Sabbag, Gavin Leech, Stephen Malina, Anastasia Kuptsova, Jake Koenig, Aleksandr Kotyurgin, Alexander Kim, Basil Halperin, Jeremy Hadfield, Steve Gadd, and Willy Chertman for reading drafts of this essay and for disagreeing with many parts of it vehemently. All errors mine.

Citation

Cite as:

Or download a BibTeX file here.

Notes

Common objections

Objection: “When I’m underslept I notice that I’m less productive.”

Answer: It might be that undersleeping itself causes you to be less productive. However, it might also be the case that there’s an upstream cause that results in both undersleeping and lack of productivity. I think either could be the case depending on the person but understanding what exactly happens is much harder than people typically appreciate when they notice such co-occurrence's.

Figure 5. Causal graph of the "staying up late and feeling demotivated and being unproductive scenario."

Objection: “Driving when you are sleepy is dangerous, therefore you are wrong.”

Answer: Yep, I agree that driving while being sleepy is dangerous and I don’t want anyone to drive, to operate heavy machinery, etc. when they are sleepy. This, however, bears no relationship on any of the arguments I make.

Objection: “The graph that shows more sleep being associated with higher doesn’t tell us anything because sick people tend to sleep more.”

Answer: It is true that some diseases lead to prolonged sleep. However, some diseases also lead to shortened sleep. For example, many stroke patients suffer from insomnia and people with fatal familial insomnia struggle with insomnia. Therefore, if you want to make the argument that the association between longer sleep and higher mortality is not indicative of the effect of sleep, you have to accept that the same is true about shorter sleep and higher mortality.

Appendix: I have no trust in sleep scientists

Why do I bother with all of this theorizing? Why do I think I can discover something about sleep that thousands of them couldn’t discover over many decades?

The reason is that I have approximately 0 trust in the integrity of the field of sleep science.

As you might be aware, 2 years ago I wrote a detailed criticism of the book Why We Sleep written by a Professor of Neuroscience at psychology at UC Berkeley, the world’s leading sleep researcher and the most famous expert on sleep, and the founder and director of the Center for Human Sleep Science at UC Berkeley, Matthew Walker.

Here are just a few of biggest issues (there were many more) with the book.

Walker wrote: “Routinely sleeping less than six or seven hours a night demolishes your immune system, more than doubling your risk of cancer”, despite there being no evidence that cancer in general and sleep are related. There are obviously no RCTs on this, and, in fact, there’s not even a correlation between general cancer risk and sleep duration.

Walker falsified a graph from an academic study in the book.

Walker outright fakes data to support his “sleep epidemic” argument. The data on sleep duration Walker presents on the graph below simply does not exist:

Figure 6. Sleep loss and obesity. Country not specified for sleep data. Copied from Walker M. Why we sleep: Unlocking the power of sleep and dreams. Simon and Schuster; 2017 Oct 3.

Here’s some actual data on sleep duration over time:

Figure 7. Association of year of study with age-adjusted total sleep time (min) for studies in which subjects followed their usual sleep schedule. Copied from Youngstedt SD, Goff EE, Reynolds AM, Kripke DF, Irwin MR, Bootzin RR, Khan N, Jean-Louis G. Has adult sleep duration declined over the last 50+ years?. Sleep medicine reviews. 2016 Aug 1;28:69-85.

By the time my review was published, the book had sold hundreds of thousands if not millions of copies and was praised by the New York Times, The Guardian, and many other highly-respected papers. It was named one of NPR’s favorite books of 2017 while Walker went on a full-blown podcast tour.

Did any sleep scientists voice the concerns they with the book or with Walker? No. They were too busy listening to his keynote at the Cognitive Neuroscience Society 2019 meeting.

Did any sleep scientists voice their concerns after I published my essay detailing its errors and fabrications? No (unless you count people replying to me on Twitter as “voicing a concern”).

Did Walker lose his status in the community, his NIH grants, or any of his appointments? No, no, and no.

I don’t believe that a community of scientists that refuses to police fraud and of which Walker is a foremost representative could be a community of scientists that would produce a trustworthy and dependable body of scientific work.

Appendix: the idea that sleep’s purpose is metabolite clearance, if not total bs, is massively overhyped

Specifically, the original 2013 paper accumulated more than 3,000 (!) citations in less than 10 years and is highly misleading.

The paper is called “Sleep Drives Metabolite Clearance from the Adult Brain”. The abstract says:

At the same time, the paper found that anesthesia without sleep results in the same clearance (paper: “Aβ clearance did not differ between sleeping and anesthetized mice”), meaning that clearance is not caused by sleep per se, but instead only co-occurrs with it. Authors did not mention this in the abstract and mistitled the paper, thus misleading the readers. As far as I can tell, literally nobody pointed this out previously.

And on top of all of this “125I-Aβ1-40 was injected intracortically”, meaning that they did not actually find any brain waste products that would be cleared out. This is an exogenous compound that was injected god knows where disrupting god knows what in the brain.

Appendix: anecdotes about acute sleep deprivation

Max Levchin in Founders at Work:

/u/CPlusPlusDeveloper on Gwern’s Writing in the Morning:

Lots of writers and software engineers note that their creative juices start flowing by evening extending late into the night - I think this phenomenon is closely related to the one described in the comment above.

Brian Timar:

Appendix: anecdotes about long-term sleep deprivation

I once tried to cheat sleep, and for a year I succeeded (strong peak-performance-sailing vibes):

James Gleck in Chaos on Mitch Feigenbaum:

Ryan Kulp’s experience with decreasing the amount of sleep by several hours:

This is a very good point that shows that: there’s (1) how sleepy we feel when waking up and (2) how sleepy we feel during the day. (2) is probably more important but most people are focused on (1) and the implicit assumption is that poor (1) leads to (2) – which is unwarranted.

Appendix: how I wake up after 6 or less hours of sleep

Nabeel Qureshi writes:

It is completely true that if you are excited by a project but it’s not super stimulating, it’s still very easy to wake up after less than usual number of hours of sleep and feel sleepy and terrible. This is true for me as well. I found a solution to this: instead of heading straight to the computer, I first unload the clean plates from the dishwasher and load it with dirty plates. This activity is quite special in that it is:

In about 90% of the cases, 10 minutes later when I’m done with the dishwasher, I find that I’m fully awake and don’t actually want to sleep anymore. In the remaining 10% of the cases, I stay awake and work until my wife wakes up and then go take a 20-minute nap under her watch (and take as many 20-minute naps as I need during the day, although I only end up taking a few naps a week and rarely more than one per day, unless I’m sick).

Appendix: Elon Musk on working 120 hours a week and sleep

CNBC:

Appendix: Philipp Streicher on homeostasis, its relationship to mania/depression, and on other points I make

Philipp (@Cautes):

Appendix: Jerome Siegel and Robert Vertes vs the sleep establishment

Time for the Sleep Community to Take a Critical Look at the Purported Role of Sleep in Memory Processing by Robert Vertes and Jerome Siegel (a reply to Walker claiming that the debate on memory processing in sleep is essentially settled):

In Memory Consolidation Is Similar in Waking and Sleep cited above, Siegel notes:

Fur Seals Suppress REM Sleep for Very Long Periods without Subsequent Rebound:

Appendix: more papers I found interesting

Long-term moderate elevation of corticosterone facilitates avian food-caching behaviour and enhances spatial memory

References

Beersma DG, Van den Hoofdakker RH. Can non-REM sleep be depressogenic?. Journal of affective disorders. 1992 Feb 1;24(2):101-8.

Bessone P, Rao G, Schilbach F, Schofield H, Toma M. The economic consequences of increasing sleep among the urban poor. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2021 Aug;136(3):1887-941.

Consensus Conference Panel:, Watson, N.F., Badr, M.S., Belenky, G., Bliwise, D.L., Buxton, O.M., Buysse, D., Dinges, D.F., Gangwisch, J., Grandner, M.A. and Kushida, C., 2015. Joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society on the recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: methodology and discussion. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 11(8), pp.931-952.

Eckert A, Karen S, Beck J, Brand S, Hemmeter U, Hatzinger M, Holsboer-Trachsler E. The link between sleep, stress and BDNF. European Psychiatry. 2017 Apr;41(S1):S282-.

Giese M, Unternährer E, Hüttig H, Beck J, Brand S, Calabrese P, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Eckert A. BDNF: an indicator of insomnia?. Molecular psychiatry. 2014 Feb;19(2):151-2.

Goldschmied JR, Rao H, Dinges D, Goel N, Detre JA, Basner M, Sheline YI, Thase ME, Gehrman PR. 0886 Recovery Sleep Significantly Decreases BDNF In Major Depression Following Therapeutic Sleep Deprivation. Sleep. 2019 Apr;42(Supplement_1):A356-.

Horne JA, Pettitt AN. High incentive effects on vigilance performance during 72 hours of total sleep deprivation. Acta psychologica. 1985 Feb 1;58(2):123-39.

Kaiser J. More than half of high-impact cancer lab studies could not be replicated in controversial analysis. AAAS Articles DO Group. 2021;

Kaplan RM, Irvin VL. Likelihood of null effects of large NHLBI clinical trials has increased over time. PloS one. 2015 Aug 5;10(8):e0132382.

Lyamin OI, Kosenko PO, Korneva SM, Vyssotski AL, Mukhametov LM, Siegel JM. Fur seals suppress REM sleep for very long periods without subsequent rebound. Current Biology. 2018 Jun 18;28(12):2000-5.

Pravosudov VV. Long-term moderate elevation of corticosterone facilitates avian food-caching behaviour and enhances spatial memory. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 2003 Dec 22;270(1533):2599-604.

Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, Tell RA, Rosenthal R. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008 Jan 17;358(3):252-60.

Rahmani M, Rahmani F, Rezaei N. The brain-derived neurotrophic factor: missing link between sleep deprivation, insomnia, and depression. Neurochemical research. 2020 Feb;45(2):221-31.

Riemann, D., König, A., Hohagen, F., Kiemen, A., Voderholzer, U., Backhaus, J., Bunz, J., Wesiack, B., Hermle, L. and Berger, M., 1999. How to preserve the antidepressive effect of sleep deprivation: A comparison of sleep phase advance and sleep phase delay. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience, 249(5), pp.231-237.

Seystahl K, Könnecke H, Sürücü O, Baumann CR, Poryazova R. Development of a short sleeper phenotype after third ventriculostomy in a patient with ependymal cysts. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2014 Feb 15;10(2):211-3.

Shen X, Wu Y, Zhang D. Nighttime sleep duration, 24-hour sleep duration and risk of all-cause mortality among adults: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Scientific Reports. 2016 Feb 22;6:21480.

Shi G, Xing L, Wu D, Bhattacharyya BJ, Jones CR, McMahon T, Chong SC, Chen JA, Coppola G, Geschwind D, Krystal A. A rare mutation of β1-adrenergic receptor affects sleep/wake behaviors. Neuron. 2019 Sep 25;103(6):1044-55.

Siegel JM. Memory Consolidation Is Similar in Waking and Sleep. Current Sleep Medicine Reports. 2021 Mar;7(1):15-8.

Sterr A, Kuhn M, Nissen C, Ettine D, Funk S, Feige B, Umarova R, Urbach H, Weiller C, Riemann D. Post-stroke insomnia in community-dwelling patients with chronic motor stroke: physiological evidence and implications for stroke care. Scientific Reports. 2018 May 30;8(1):8409.

Vertes RP, Siegel JM. Time for the sleep community to take a critical look at the purported role of sleep in memory processing. Sleep. 2005 Oct 1;28(10):1228-9.

Xie L, Kang H, Xu Q, Chen MJ, Liao Y, Thiyagarajan M, O’Donnell J, Christensen DJ, Nicholson C, Iliff JJ, Takano T. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. science. 2013 Oct 18;342(6156):373-7.

Yetish G, Kaplan H, Gurven M, Wood B, Pontzer H, Manger PR, Wilson C, McGregor R, Siegel JM. Natural sleep and its seasonal variations in three pre-industrial societies. Current Biology. 2015 Nov 2;25(21):2862-8.

Youngstedt SD, Goff EE, Reynolds AM, Kripke DF, Irwin MR, Bootzin RR, Khan N, Jean-Louis G. Has adult sleep duration declined over the last 50+ years?. Sleep medicine reviews. 2016 Aug 1;28:69-85.