I'm pretty sure this point is just ... uh... wrong:

But the deeper reason is that there’s really no such thing as a natural resource. All resources are artificial. They are a product of technology. And economic growth is ultimately driven, not by material resources, but by ideas.

That is to say, I think that you can't have NOTHING BUT ideas and have the kind of economic growth that matters to humans in human bodies.

The point of having a word like "natural resources" is to distinguish the subset of resources that really do seem to be physically existing things.

Energy is pretty central example here for me. There are finite calories. If we don't have enough calories then we starve. If we don't have enough calories then we can't move our bodies from place to place.

In The Machine Stops Forster portrayed a civilization that had turned the knob pretty far in the direction of "high hedonic/humanistic satisfaction per calorie" (also per NEW atom) but they still needed some calories, and also all the atoms that they used to build The Machine in the first place.

Calories seem less substitutable to me than atoms.

Maybe it is hypothetically possible to go really deep into some sort of reversible computing paradigm, but ultimately every thought that is worth thinking before other thoughts needs to be sped up, and that irreversibility will cost energy.

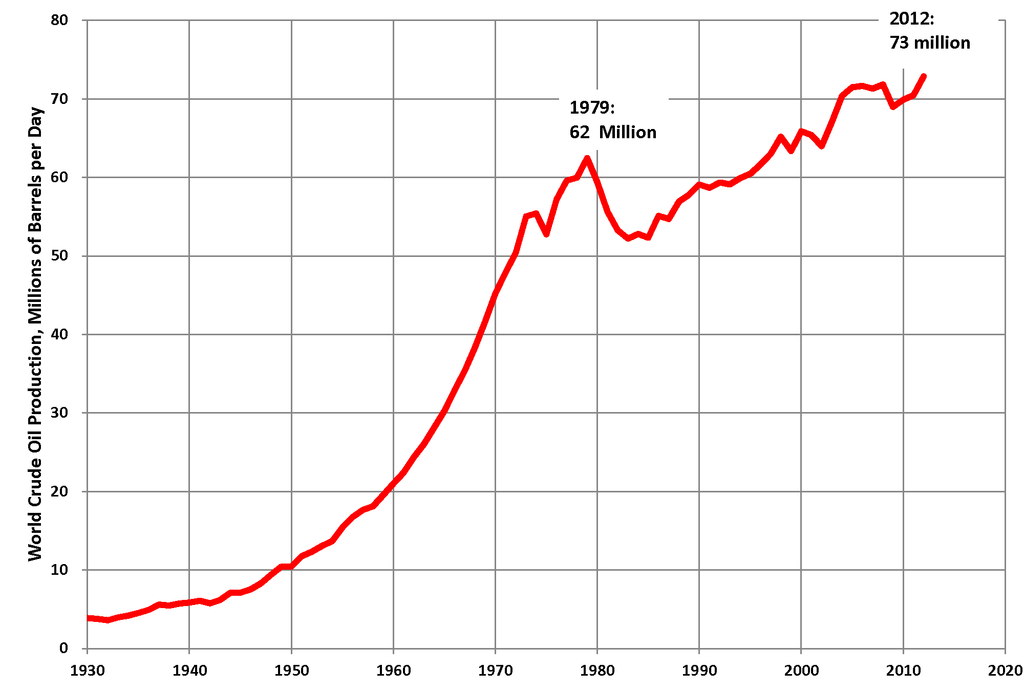

So many people are confused about "wtf happened in 1971?" and one of the really big ones is: we stopped having exponential growth in energy which is a necessary natural resource for prosperity.

(I think the deep cause of this historical problem, and several other historical problems, is that the government and elites stopped being competent, unified, and benevolent. But that's a separate matter, perhaps, and is harder to show on graphs.)

You offered this graph above but it seems like it cleanly explains how there was justifiable and large optimism in the 1950s and 1960s about the median standard of living because of energy, and then there was a train wreck and now we're living in the ruins of that civilization:

But like... there are obvious mechanisms linking "energy --> wealth --> happiness", and also the large scale structure of the global economy lines up in the way that it probably should, given the obvious mechanisms:

(Image here is taken from Figure 1 of Energetic Limits To Economic Growth.)

So maybe I'm missing something?

If you see some reason to expect wealth to fall out of the sky based on ONLY some clever idea, that would be good news to me and I would love to be wrong, but my current working theory is that the core thing that has to be true to produce radically good social outcomes is more calories per capita per year.

Ideas are important too in my model... but like... look at the Internet and the funding of the NSF. Ideas are doing fine :-)

But ONE of the important good ideas you need to have (that it seems like we are missing) is, roughly: "Natural resources are necessary inputs into wealth and human flourishing and we should coordinate to do more and better natural resource extraction because doing so will cause more wealth and human flourishing to exist."

I think this idea breaking down in the median voter in the west is a cause of a lot of the sadness of the current global situation (China excepted, because they are correctly focused on ramping up energy for the good of China, like any sane society would and should).

It is kind of tragic because if the opposite of this idea motivates the opposite of correct actions at an aggregate level, then unilaterally sane people might actually be punished by the government, rather than profiting from their unique correctness, and the prospects for our society in general would be quite bleak. It is hard to get the median voter to be right about something where they are already wrong as part of the status quo, and they've been wrong for decades, and their wrongness only hurts "everyone, in the long run" rather than "themselves, in the short run".

This is part of why I'd love to hear that I'm wrong. I think natural material wealth (especially energy sources) cause prosperity.

However, few people seem to explicitly believe this? You seem to not believe it here? And government policy isn't generally organized around the idea that "energy resources are actually super important"...

If I'm wrong then I get to have more hope, and who wouldn't want some justified hope? Is there some way I'm obviously wrong here? :-)

I basically agree with all of the first part of this, but towards the end it seems to miss a very important point. You say

we should coordinate to do more and better natural resource extraction because doing so will cause more wealth and human flourishing to exist

but some natural resources are in fact limited (with hard limits and/or soft ones where the costs go up drastically as you try to extract more), which means that doing more natural resource extraction now may mean having to do less in the future, and the damage done by running out may be less if we do it more gradually starting earlier.

Historically, people arguing for limiting resource-extraction have tended to turn out to have been too pessimistic about the limits, but that doesn't mean there are no limits.

For instance: you showed that graph of crude oil extraction. A crude fit to the bit before 1971 is daily_megabarrels = 0.323 exp(0.070(year-1900)). If we suppose that the only reason reality stopped matching this is that "elites stopped being competent, unified and benevolent" and imagine continuing on that trajectory, then by the year 2100 the total amount of oil extracted (since 1930) would be about 2 quadrillion barrels. The actual figure to date is about 1 trillion. It does not seem plausible to me that there is 2000x as much oil extractible at any cost as the total amount we have extracted so far. Even by 2022, the model suggests ~8 trillion barrels extracted, or about 8x what actually has been; it seems highly plausible that that's more than there is, or at any rate more than can be extracted at reasonable cost.

(Is the exponential model unreasonably pessimistic? Well, your own description of what was happening before 1971 was, specifically, "exponential growth in energy". If we don't mind using 4 parameters instead of 2 we can get about as good a fit as the exponential above -- daily_megabarrels = 4.73 + 1.96e-5(y-1921.6)^3.74. In that case, total extraction to 2100 would be "only" 70x what we have actually extracted to date.)

(Is it unreasonable for me to be talking specifically about oil when what matters is total energy? It might be, if I were arguing specifically that we shouldn't be aiming to get a lot of energy. But I'm not arguing that; perhaps we should be aiming for that; my point is just that specific resources may be meaningfully depletable, and that that means that some things under the heading of "more and better natural resource extraction" could actually be bad ideas.)

So we should definitely coordinate to do more efficient resource extraction, and to find ways to use effectively-unlimited resources like sunlight, but for resources we might realistically run out of some time in the foreseeable future there's a tradeoff between prosperity now and possible collapse later and in some of these cases we may instead need to coordinate on extracting less.

(Important complication: extracting more now may help us with figuring out ways to be more efficient, finding new resources, and mitigating the damage when we run out, in which case we should be extracting faster than simpler models of the tradeoff would suggest.)

I'm friendly to basically everything you've said, gjm ;-)

Once we are thinking in terms of collecting certain kinds of important resources now versus saving those important resources for some time in the deeper future...

...we're already working with the core premise: that there ARE important resources (and energy is one of the most important).

Details about early or late usage of this or that resource are (relatively speaking) details.

Oil and coal are not things I'm not particularly in love with. Thorium might be better, I think? The sun seems likely to be around for a LONG time and solar panels in space seems like an idea with a LOT of room to expand!

There has to be "ideas" here (jason's OP on ideas is right that they matter), but I think the ideas have to be ABOUT energy and atoms and physical plans for those ideas to to turn into something that makes human lives better.

(Image source!) In practice, right now: oil and coal are our primary sources. For Earth right now, solar is still negligible, but if eventually we have asteroid minining and space solar arrays, I'd expect (and hope!) that that stuff would become the dominating term in the energy budget.

The idea of just "putting an end to all that fossil fuel stuff" in the near future seems either confused or evil to me. EITHER people proposing that might be UNAWARE of the entailment in terms of human misery of halting this stuff without having something better ready to go, OR ELSE they might be AWARE of the consequences and misanthropically delighted with the idea of fewer humans doing fewer things?

I'm pro-human. Hence I'm pro-energy.

I think climate change might be an "elephant in the room" when it comes to energy policy?

But I'm also in favor of weather and climate control if we can get those too... Like my answer is "optimism" and "moar engineering!" to basically everything.

Controlling the climate will take MORE resources to accomplish, not less! If, for example, humans are going to reverse the desertification of the Sahara, and use the new forests as carbon sinks, that will be a HUGE project that involves moving around a LOT of dirt and water and seeds and chemistry and so on. I'm not precisely sure that fixing the Sahara would be the specific best use of resources, but I do think that whatever the right ideas are, they have to be ideas about resources and atoms and physical reality.

I disagree, strongly. Not only do I believe this line of reasoning to be wrong, I believe it to be dangerously wrong. I believe downplaying and/or underestimating the role of energy in our economic system is part of why we find ourselves in the mess we're in today.

To reference Nate Hagens (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-xr9rIQxwj4)

We use the equivalent of 100 billion barrels of oil a year. Each barrel of oil can do the amount of work it would take 5 humans to do. There are 500 billion 'ghost' labourers in our society today.

(Back to me)

You cannot eat ideas. You cannot treat sewage with them. You cannot heat your home with them. You cannot build your home with them. You cannot travel across an ocean on them.

1000x0 is 0. Technology is a powerful multiplier, but 0 is 0.

You cannot build cold fusion power plants with ideas. You cannot conjure up the material resources or the skilled labour and energy inputs necessary to build them with ideas. (once again Nate Hagens - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O0pt3ioQuNc)

.... aaaand then there's the whole topic of renewables and the hidden costs and limitations thereof.

The only idea I have encountered that nullifies this reality is a superintelligent AI. The thing we're all so scared of, but simultaneously the only technology powerful enough to both harvest and utilize energy on scales beyond human ability. And also powerful enough to coordinate human activity such that Jeavons Paradox doesn't nullify the benefits (and, more generally, such that we don't waste such an insane amount of energy on stupid things).

And finally, re population:

Demographics, read about them - https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/40697556-the-human-tide

tl;dr Yes, Malthus was 'wrong'. He was wrong because it turned out that women with access to education and opportunity choose to have less children (there are exceptions, but not too many). Technology/ideas didn't save us from exponential population growth, it was a natural (i.e. not consciously considered, organized, enacted) change in behaviour.

I would like to think about this more, but thank you for posting this and switching my mind from System I to System II

We may not run out of ideas but we may run out of exploitable physics. For instance what is most needed at the moment is a clean, cheap and large scale energy source that can replace gas, oil, and coal, without which much of the technological and economic development of the last hundred and fifty years or so would have been impossible. Perhaps fusion can be that thing. Perhaps we can paper over the Sahara with photovoltaics. Perhaps we can design fail-safe fission reactors more acceptable to the general population. Let’s assume we will solve the various technical and geopolitical problems necessary to get at least one of these technologies to where we need it to be. My point is this, what if physics either didn’t allow, or made it technologically too difficult; for any of these three possibilities to come to fruition ? We’d be at roughly the same place in terms of development, but without the potential safety net these technologies could give us. What likelihood of continued progress then? And so on. A greater population (of humans at least) in the future will certainly provide a greater fund of technological ideas, but to keep the world in a healthy enough state to support that population may require physics that is either unavailable to us, or just too difficult to exploit.

In regard to the amazing possibilities available to us by manipulating macromolecules, I am completely with you. We have only just scratched the surface of what is achievable using the physics we have readily to hand, IMO.

I basically agree. Growth will hit some limit set by the laws of physics in at most single-digit thousands of years. But there are orders of magnitude of headroom between here and there

One could argue that at least some of the growth is not a measurement of increased human satisfaction, but just of Goodheart mismeasurement and nefarious schemes of the wealthy to increase their power at the expense of the common man.

GDP is a classic example of a measure that has changed meaning over time. Take the simple example of neighbors who each mow their lawns every week. It's unmeasured, but valuable enough for them to do it. Then one neighbor starts to do both lawns, and the other reciprocates with taking care of all the kids during the day. Also great value, good specialization, improved welfare. But if they decide to PAY each other for the services, nothing changes about the work performed or value received, but now GDP is up by twice the value exchanged (each pays the other $x, for $2x gdp measurement).

To some degree every available happiness metric is a goodhart, but people in places like Bangalore seem justifiably keen on moving to the high GDP countries. I think the thing that makes GDP per capita PPP or the highly correlated "median income" reliable as proxies for national well being, is that (non-Chinese) governments tend to be really unaggressive at "optimizing" them.

Given the horrifically inefficient way we are using our current idea-creating resources (people), it seems a much better investment to improve our efficiency, rather than creating more underutilized resources at great expense.

The number of potential molecular compounds, or the number of possible DNA sequences, is astronomical. We have barely begun to explore.

Hate to say it, but most DNA sequences/molecular compounds are probably useless. The Library of Babel is far less than 0.000001% good novels, for instance.

Of course they are. The point is that there must be some amazing ones hiding in that enormous haystack.

Quoting Romer:

To see how far this kind of process can take us, imagine the ideal chemical refinery. It would convert an abundant, renewable resource into a product that humans value. It would be smaller than a car, mobile so that it could search out its own inputs, capable of maintaining the temperature necessary for its reactions within narrow bounds, and able to automatically heal most system failures. It would build replicas of itself for use after it wears out, and it would do all of this with little human supervision. All we would have to do is get it to stay still periodically so that we could hook up some pipes and drain off the final product.

This refinery already exists. It is the milk cow. Nature found this amazing way to arrange hydrogen, carbon, and a few other miscellaneous atoms by meandering along one particular evolutionary path of trial and error (albeit one that took hundreds of millions of years). Someone who had never heard of a cow or a bat probably would not believe that a hunk of atoms can turn grass into milk or navigate by echolocation as it flies around. Imagine all the amazing things that can be made out of atoms that simply have never been tried.

[EDIT: This comment is a bit of a mess, but I haven't figured out yet how to make the reasoning more solid.]

Regarding productivity specifically, it seems relevant that AGI+robotics leads to infinite labor productivity. The reason is that it obsoletes (human) labor, so capital no longer requires any workers to generate output.

Therefore, for there to be any finite limit on labor productivity, it'd need to be the case that AGI+robotics is never developed. That situation, even considered on its own, seems surprising: maybe AGI somehow is physically impossible, or there's some (non-AGI-related) catastrophe leading to permanent collapse of civilization, or even if AGI is physically possible it's somehow not possible to invent it, etc. A lot of those reasons would themselves pose problems for technological progress generally: for example, if a catastrophe prevented inventing AGI, it probably prevented inventing a lot of other advanced technology too.

It could also be understood that hitting the AI condition means that human labor productivity becomes 0. Part of the disparity problem would be that we might need to find a new reasoning to give humans resoures aside from economical neccesity.

It could also be understood that hitting the AI condition means that human labor productivity becomes 0.

I don't agree with this. Using the formula "labor productivity = output volume / labor input use" (which I grabbed from Wikipedia, which is maybe not the best source, but it seems right to me), if "labor input use" is zero and "output volume" is positive, then "labor productivity" is +infinity.

Division by zero is undefined and it not guaranteed to correspond to +infinity in all context. In this context there might be a difference whether we are talking about the limit when labor apporaches 0 and when labour is completely absent. This is the difference between paying your employees 2 cents and not having employees at all. If you don't have to get the inputs you waste zero resources bargaining for them and a firm that pays no wages is not enriching anyone (by proleriat mode).

If you are benetting from a gift that you don't have to work for at all it not like you "work at infinite efficiency" for it. You can get "infinite moon dust efficiency" by not using any moon dust. But if your goal is to make a margarita moon dust is useless instead of being supremely helpful.

Division by zero is undefined and it not guaranteed to correspond to +infinity in all context. In this context there might be a difference whether we are talking about the limit when labor apporaches 0 and when labour is completely absent.

True, and in this context the limiting value when approaching from above is certainly the appropriate interpretation. After all, we're talking about a gradual transition from current use of labor (which is positive) to zero use of labor. If the infinity is still bothersome, imagine somebody is paid to spend 1 second pushing the "start the AGI" button, in which case labor productivity is a gazillion (some enormous finite number) instead of infinity.

If you are benetting from a gift that you don't have to work for at all it not like you "work at infinite efficiency" for it.

You seem to be arguing against the definition of labor productivity here. I think though that I'm using the most common definition. If you consider for example Our World In Data's "productivity per hour worked" graph, it uses essentially the same definition that I'm using.

i think this piece would benefit from a few examples of historic ideas which boosted the labor productivity multiple. it’s not clear to me why ideas aren’t treated as just a specific “type” of capital: if the ideas you’re thinking of are things like “lean manufacturing” or “agile development”, these all originated under existing capital structures and at one time had specific “owners” (like Toyota). we have intellectual property laws, so some of these ideas can be owned: they operate as an enhancement to labor productivity and even require upkeep (depreciation) to maintain: one has to teach these ideas to new workers. so they seem like a form of capital to me.

my suspicion is that these “ideas” are just capital which has escaped any concrete ownership. they’re the accumulation of positive externalities. it’s worth noting that even once these ideas escape ownership, they don’t spread for free: we have schools, mentorship, etc. people will voluntarily participate in the free exchange of ideas (e.g. enthusiast groups), but that doesn’t mean there’s no upkeep in these ideas: it just isn’t financialized. in the end, a new idea displacing an old one doesn’t look all that different from a more efficient (higher output per input) machine displacing a less efficient machine: they’re both labor productivity enhancements which require some capital input to create and maintain.

“Ideas which boosted the labor productivity multiple”: pretty much every major technology! Mechanization, the factory system, engines, electricity, etc.

Why ideas are treated distinct from capital is a good question. Basically, it is a matter of economic accounting. In a nutshell: We can measure the amount of money invested in capital equipment, and we can measure the increase in labor productivity (output produced per worker-hour). And it turns out that productivity increases much faster than capital investment. The residual is chalked up to technology.

The difference between ideas and physical capital is that the former is nonrival (although, with intellectual property, partially excludable).

Much more explanation and history in this draft essay of mine: https://progressforum.org/posts/W6cSxas75tN8L47e6/draft-for-comment-ideas-getting-harder-to-find-does-not

(Note that it's important to differentiate between ideas as such, and ideas as learned/understood by humans. The latter is more like capital, indeed it is referred to as “human capital.” See here and here.)

If I understand correctly, discussions of superintelligence imply that a 'friendly' AGI would provide for exponentially increasing TFP growth while effective number of researchers could remain flat or decline.

Additionally, number of researchers as a share of the total human population could be flat or decline, because AGI would do all the thinking, and do it better than any human or assemblage of humans could.

If AGI points out that physics does not permit overcoming energy scarcity, and space travel/colonization is not viable for humans due to engineering challenges actually being insurmountable, then an engineered population crash is the logical thing to do in order to prolong human existence.

So a friendly AI would, in that environment, end up presiding over a declining mass of ignorant humans with the assistance of a small elite of AI technicians who keep the machine running.

I don't think that my first two paragraphs here are correct, but I think that puts me in a minority position here.

I gave a five-minute talk talk for Ignite Long Now 2022. It’s a simplified and very condensed treatment of a complex topic. The video is online; below is a transcript with selected visuals and added links.

Humanity has had a pretty good run so far. In the last two hundred years, world GDP per capita has increased by almost fourteen times:

But “past performance may not be indicative of future results.” Can growth continue?

One argument against long-term growth is that we will run out of resources. Malthus worried about running out of farm land, Jevons warned that Britain would run out of coal, and Hubbert called Peak Oil.

Fears of shortages lead to fears of “overpopulation”. If resources are static, then they have to be divided into smaller and smaller shares for more and more people. In the 1960s, this led to dire predictions of famine and depredation:

But predictions of catastrophic shortages virtually never come true. Agricultural productivity has grown faster than Malthus realized was possible. And oil production, after a temporary decline, recently hit at an all-time high:

One reason is that predictions of shortages are based on conservative estimates from only proven reserves. Another is that when a resource really is running out, we transition off of it—as, in the 1800s, we switched our lighting from whale oil to kerosene.

But the deeper reason is that there’s really no such thing as a natural resource. All resources are artificial. They are a product of technology. And economic growth is ultimately driven, not by material resources, but by ideas.

In the 20th century, the crucial role of ideas was confirmed by formal economic models. The economist Robert Solow was studying how output per worker increases as we accumulate capital, such as machines and factories. There are diminishing returns to capital accumulation alone. A single worker who is given two machines can’t be twice as productive. So if technology is static, output per worker soon stops growing:

But technology acts as a multiplier on productivity. This makes each worker more productive, and creates more headroom for capital accumulation:

So we can have economic growth if, and only if, we have technological progress.

How does this happen? Another economist, Paul Romer, pointed out the key feature of ideas: In economic terms, they are “nonrival”. Unlike a loaf of bread, or a machine, an invention or an equation can be shared by everyone. If we double the number of workers we have and double the machines they use, we will merely double their output, which is the same output per worker. But if we also double the power of technology, we will more than double output, making everyone richer. Physical resources have to be divided up, so as the population grows, the per-capita stock of resources shrinks. But ideas do not. The per-capita stock of ideas is the total stock of ideas.

So we won’t run out of resources, as long as we keep generating new ideas. But—will we run out of ideas?

Romer assumed that the technology multiplier would grow exponentially at a rate proportional to the number of researchers. But another economist, Chad Jones, pointed out that in the 20th century, we have vastly increased R&D, while growth rates have been flat or even declining. This is evidence that ideas have been getting harder to find:

Does this mean inevitable stagnation? Maybe we have already picked all the low-hanging fruit. Maybe research is like mining for ideas, and the vein is running thin. Maybe inventions are like fish in a pond, and the pond is getting fished out. But notice that all these metaphors treat ideas like physical resources! And I think it’s a mistake to call “peak ideas”, just as it’s always been a mistake to call peak resources.

One reason, as Paul Romer pointed out, is that the space of ideas is combinatorially vast. The number of potential molecular compounds, or the number of possible DNA sequences, is astronomical. We have barely begun to explore.

And even as ideas get harder to find, we get better at finding them. As the population and the economy grow, we can devote more brains and more investment to R&D. And technologies like spreadsheets or the Internet make researchers more productive.

In fact, the greatest threat to long-term economic growth might be the slowdown in population growth:

Without more brains to push technology forward, progress might stall.

Now, that’s a problem for another time. But note that in five minutes we’ve gone from worrying about overpopulation to underpopulation. That’s because we’ve traded a scarcity mindset, where growth is limited by resources, for an abundance mindset, where it is limited only by our ingenuity.

Thanks to Brady Forrest and the Long Now Foundation for inviting me to speak.