(This is the first post of a new Sequence, Highly Advanced Epistemology 101 for Beginners, setting up the Sequence Open Problems in Friendly AI. For experienced readers, this first post may seem somewhat elementary; but it serves as a basis for what follows. And though it may be conventional in standard philosophy, the world at large does not know it, and it is useful to know a compact explanation. Kudos to Alex Altair for helping in the production and editing of this post and Sequence!)

I remember this paper I wrote on existentialism. My teacher gave it back with an F. She’d underlined true and truth wherever it appeared in the essay, probably about twenty times, with a question mark beside each. She wanted to know what I meant by truth.

-- Danielle Egan

I understand what it means for a hypothesis to be elegant, or falsifiable, or compatible with the evidence. It sounds to me like calling a belief ‘true’ or ‘real’ or ‘actual’ is merely the difference between saying you believe something, and saying you really really believe something.

-- Dale Carrico

What then is truth? A movable host of metaphors, metonymies, and; anthropomorphisms: in short, a sum of human relations which have been poetically and rhetorically intensified, transferred, and embellished, and which, after long usage, seem to a people to be fixed, canonical, and binding.

-- Friedrich Nietzche

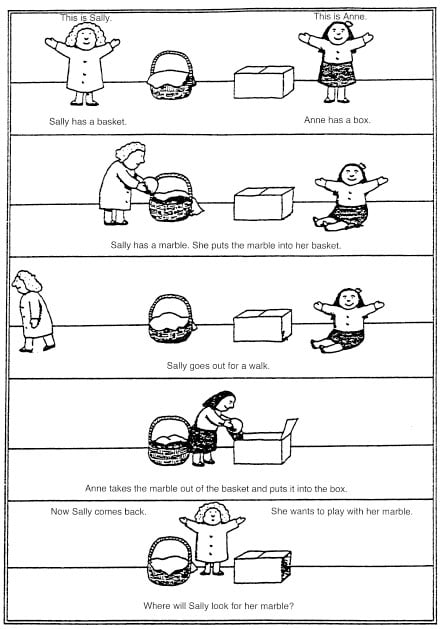

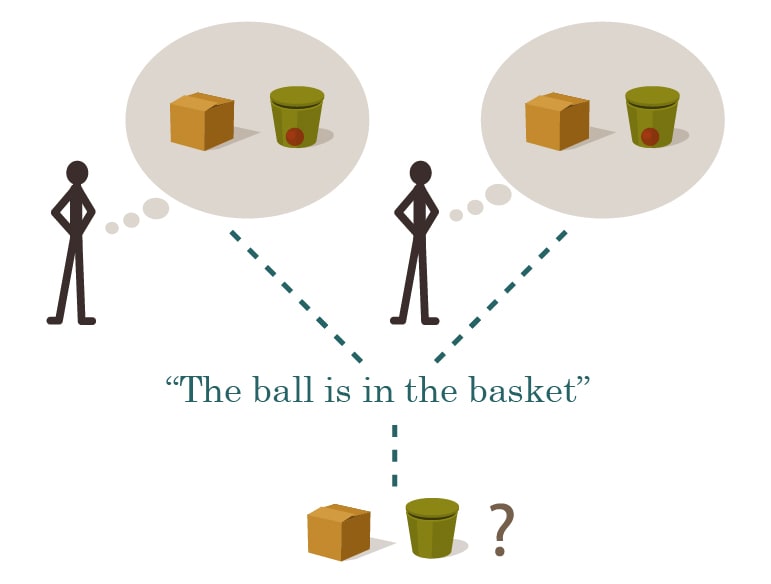

The Sally-Anne False-Belief task is an experiment used to tell whether a child understands the difference between belief and reality. It goes as follows:

The child sees Sally hide a marble inside a covered basket, as Anne looks on.

Sally leaves the room, and Anne takes the marble out of the basket and hides it inside a lidded box.

Anne leaves the room, and Sally returns.

The experimenter asks the child where Sally will look for her marble.

Children under the age of four say that Sally will look for her marble inside the box. Children over the age of four say that Sally will look for her marble inside the basket.

(Attributed to: Baron-Cohen, S., Leslie, L. and Frith, U. (1985) ‘Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind”?’, Cognition, vol. 21, pp. 37–46.)

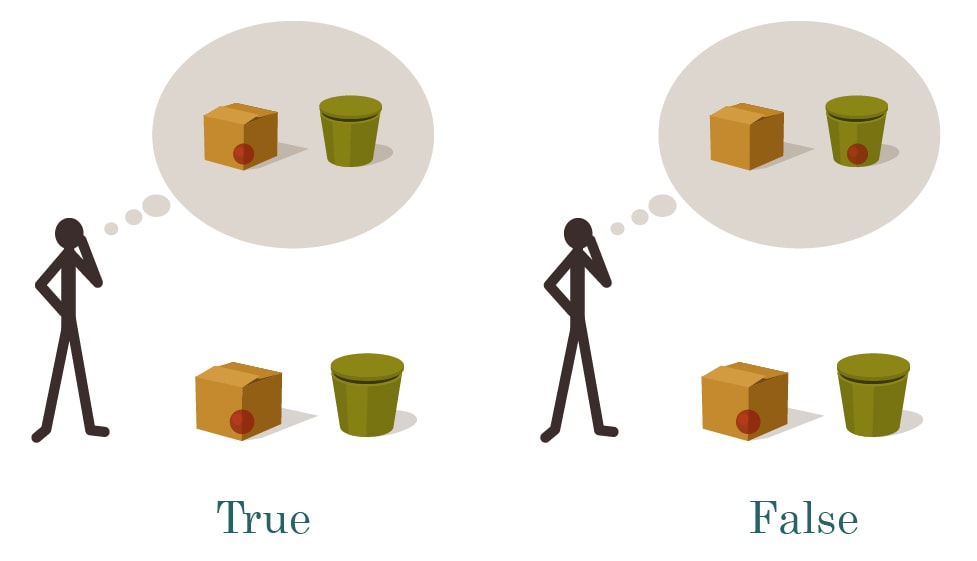

Human children over the age of (typically) four, first begin to understand what it means for Sally to lose her marbles - for Sally's beliefs to stop corresponding to reality. A three-year-old has a model only of where the marble is. A four-year old is developing a theory of mind; they separately model where the marble is and where Sally believes the marble is, so they can notice when the two conflict - when Sally has a false belief.

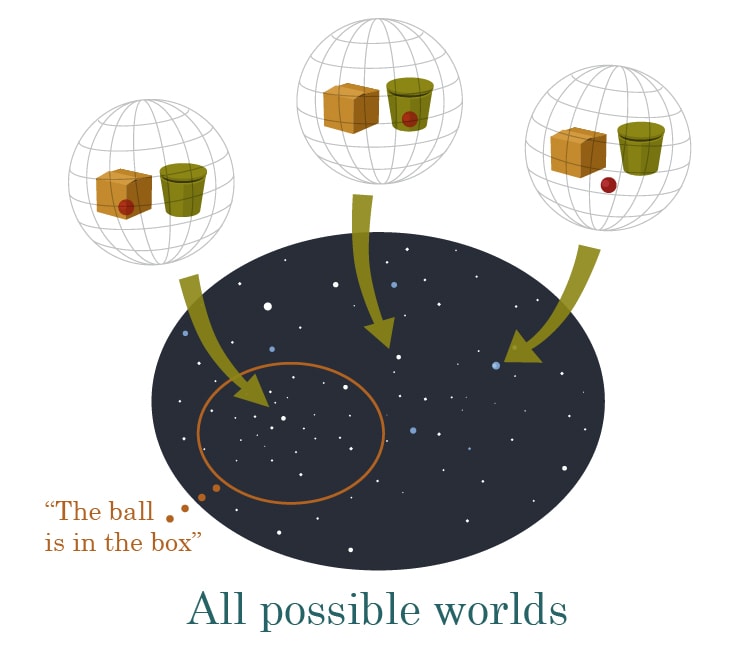

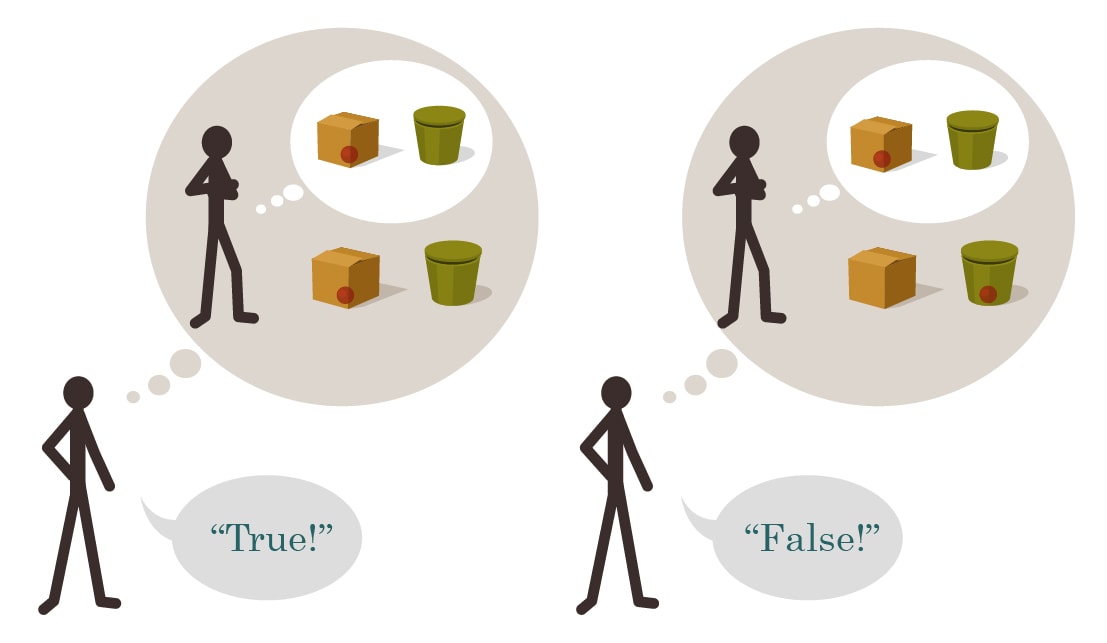

Any meaningful belief has a truth-condition, some way reality can be which can make that belief true, or alternatively false. If Sally's brain holds a mental image of a marble inside the basket, then, in reality itself, the marble can actually be inside the basket - in which case Sally's belief is called 'true', since reality falls inside its truth-condition. Or alternatively, Anne may have taken out the marble and hidden it in the box, in which case Sally's belief is termed 'false', since reality falls outside the belief's truth-condition.

The mathematician Alfred Tarski once described the notion of 'truth' via an infinite family of truth-conditions:

The sentence 'snow is white' is true if and only if snow is white.

The sentence 'the sky is blue' is true if and only if the sky is blue.

When you write it out that way, it looks like the distinction might be trivial - indeed, why bother talking about sentences at all, if the sentence looks so much like reality when both are written out as English?

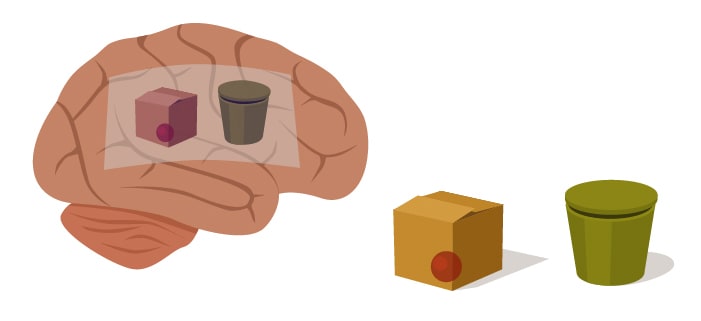

But when we go back to the Sally-Anne task, the difference looks much clearer: Sally's belief is embodied in a pattern of neurons and neural firings inside Sally's brain, three pounds of wet and extremely complicated tissue inside Sally's skull. The marble itself is a small simple plastic sphere, moving between the basket and the box. When we compare Sally's belief to the marble, we are comparing two quite different things.

(Then why talk about these abstract 'sentences' instead of just neurally embodied beliefs? Maybe Sally and Fred believe "the same thing", i.e., their brains both have internal models of the marble inside the basket - two brain-bound beliefs with the same truth condition - in which case the thing these two beliefs have in common, the shared truth condition, is abstracted into the form of a sentence or proposition that we imagine being true or false apart from any brains that believe it.)

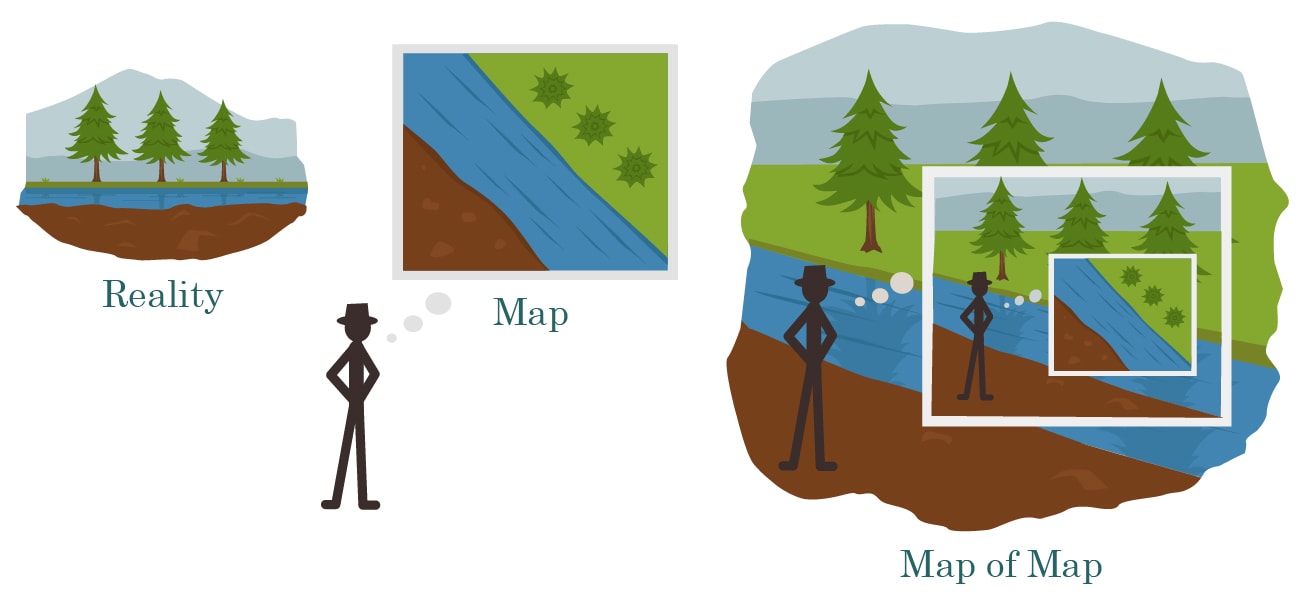

Some pundits have panicked over the point that any judgment of truth - any comparison of belief to reality - takes place inside some particular person's mind; and indeed seems to just compare someone else's belief to your belief:

So is all this talk of truth just comparing other people's beliefs to our own beliefs, and trying to assert privilege? Is the word 'truth' just a weapon in a power struggle?

For that matter, you can't even directly compare other people's beliefs to our own beliefs. You can only internally compare your beliefs about someone else's belief to your own belief - compare your map of their map, to your map of the territory.

Similarly, to say of your own beliefs, that the belief is 'true', just means you're comparing your map of your map, to your map of the territory. People usually are not mistaken about what they themselves believe - though there are certain exceptions to this rule - yet nonetheless, the map of the map is usually accurate, i.e., people are usually right about the question of what they believe:

And so saying 'I believe the sky is blue, and that's true!' typically conveys the same information as 'I believe the sky is blue' or just saying 'The sky is blue' - namely, that your mental model of the world contains a blue sky.

Meditation:

If the above is true, aren't the postmodernists right? Isn't all this talk of 'truth' just an attempt to assert the privilege of your own beliefs over others, when there's nothing that can actually compare a belief to reality itself, outside of anyone's head?

(A 'meditation' is a puzzle that the reader is meant to attempt to solve before continuing. It's my somewhat awkward attempt to reflect the research which shows that you're much more likely to remember a fact or solution if you try to solve the problem yourself before reading the solution; succeed or fail, the important thing is to have tried first . This also reflects a problem Michael Vassar thinks is occurring, which is that since LW posts often sound obvious in retrospect, it's hard for people to visualize the diff between 'before' and 'after'; and this diff is also useful to have for learning purposes. So please try to say your own answer to the meditation - ideally whispering it to yourself, or moving your lips as you pretend to say it, so as to make sure it's fully explicit and available for memory - before continuing; and try to consciously note the difference between your reply and the post's reply, including any extra details present or missing, without trying to minimize or maximize the difference.)

...

...

...

Reply:

The reply I gave to Dale Carrico - who declaimed to me that he knew what it meant for a belief to be falsifiable, but not what it meant for beliefs to be true - was that my beliefs determine my experimental predictions, but only reality gets to determine my experimental results. If I believe very strongly that I can fly, then this belief may lead me to step off a cliff, expecting to be safe; but only the truth of this belief can possibly save me from plummeting to the ground and ending my experiences with a splat.

Since my expectations sometimes conflict with my subsequent experiences, I need different names for the thingies that determine my experimental predictions and the thingy that determines my experimental results. I call the former thingies 'beliefs', and the latter thingy 'reality'.

You won't get a direct collision between belief and reality - or between someone else's beliefs and reality - by sitting in your living-room with your eyes closed. But the situation is different if you open your eyes!

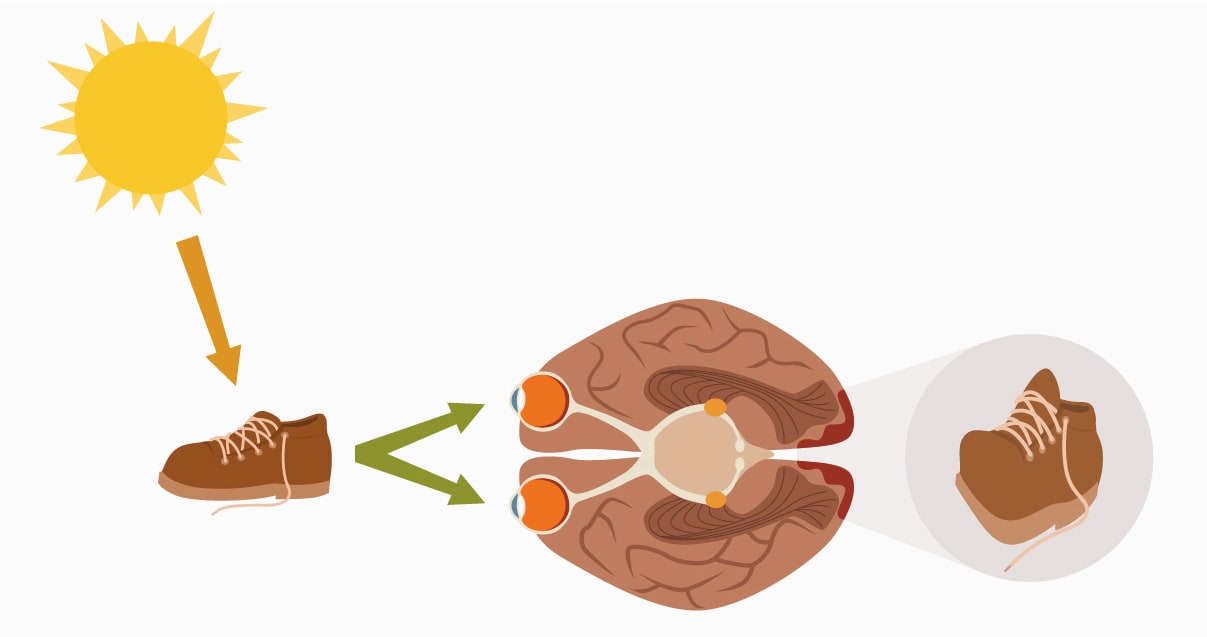

Consider how your brain ends up knowing that its shoelaces are untied:

- A photon departs from the Sun, and flies to the Earth and through Earth's atmosphere.

- Your shoelace absorbs and re-emits the photon.

- The reflected photon passes through your eye's pupil and toward your retina.

- The photon strikes a rod cell or cone cell, or to be more precise, it strikes a photoreceptor, a form of vitamin-A known as retinal, which undergoes a change in its molecular shape (rotating around a double bond) powered by absorption of the photon's energy. A bound protein called an opsin undergoes a conformational change in response, and this further propagates to a neural cell body which pumps a proton and increases its polarization.

- The gradual polarization change is propagated to a bipolar cell and then a ganglion cell. If the ganglion cell's polarization goes over a threshold, it sends out a nerve impulse, a propagating electrochemical phenomenon of polarization-depolarization that travels through the brain at between 1 and 100 meters per second. Now the incoming light from the outside world has been transduced to neural information, commensurate with the substrate of other thoughts.

- The neural signal is preprocessed by other neurons in the retina, further preprocessed by the lateral geniculate nucleus in the middle of the brain, and then, in the visual cortex located at the back of your head, reconstructed into an actual little tiny picture of the surrounding world - a picture embodied in the firing frequencies of the neurons making up the visual field. (A distorted picture, since the center of the visual field is processed in much greater detail - i.e. spread across more neurons and more cortical area - than the edges.)

- Information from the visual cortex is then routed to the temporal lobes, which handle object recognition.

- Your brain recognizes the form of an untied shoelace.

And so your brain updates its map of the world to include the fact that your shoelaces are untied. Even if, previously, it expected them to be tied! There's no reason for your brain not to update if politics aren't involved. Once photons heading into the eye are turned into neural firings, they're commensurate with other mind-information and can be compared to previous beliefs.

Belief and reality interact all the time. If the environment and the brain never touched in any way, we wouldn't need eyes - or hands - and the brain could afford to be a whole lot simpler. In fact, organisms wouldn't need brains at all.

So, fine, belief and reality are distinct entities which do intersect and interact. But to say that we need separate concepts for 'beliefs' and 'reality' doesn't get us to needing the concept of 'truth', a comparison between them. Maybe we can just separately (a) talk about an agent's belief that the sky is blue and (b) talk about the sky itself.

Maybe we could always apply Tarski's schema - "The sentence 'X' is true iff X" - and replace every invocation of the word 'truth' by talking separately about the belief and the reality.

Instead of saying:

"Jane believes the sky is blue, and that's true",

we would say:

"Jane believes 'the sky is blue'; also, the sky is blue".

Both statements convey the same information about (a) what we believe about the sky and (b) what we believe Jane believes.

And thus, we could eliminate that bothersome word, 'truth', which is so controversial to philosophers, and misused by various annoying people!

Is that valid? Are there any problems with that?

Suppose you had a rational agent, or for concreteness, an Artificial Intelligence, which was carrying out its work in isolation and never needed to argue politics with anyone.

This AI has been designed [note for modern readers: this is back when AIs were occasionally designed rather than gradient-descended, the AI being postulated is not a large language model] around a system philosophy which says to separately talk about beliefs and realities rather than ever talking about truth.

This AI (let us suppose) is reasonably self-aware; it can internally ask itself "What do I believe about the sky?" and get back a correct answer "I believe with 98% probability that it is currently daytime and unclouded, and so the sky is blue." It is quite sure that this probability is the exact statement stored in its RAM.

Separately, the AI models that "If it is daytime and uncloudy, then the probability that my optical sensors will detect blue out the window is 99.9%. The AI doesn't confuse this proposition with the quite different proposition that the optical sensors will detect blue whenever it believes the sky is blue. The AI knows that it cannot write a different belief about the sky to storage in order to control what the sensor sees as the sky's color.

The AI can differentiate the map and the territory; the AI knows that the possible states of its RAM storage do not have the same consequences and causal powers as the possible states of sky.

If the AI's computer gets shipped to a different continent, such that the AI then looks out a window and sees the purple-black of night when the AI was predicting the blue of daytime, the AI is surprised but not ontologically confused. The AI correctly reconstructs that what must have happened was that the AI internally stored a high probability of it being daytime; but that outside in actual reality, it was nighttime. The AI accordingly updates its RAM with a new belief, a high probability that it is now nighttime.

The AI is already built so that, in every particular instance, its model of reality (including its model of itself) correctly states points like:

- If I believe it's daytime and cloudless, I'll predict that my sensor will see blue out the window;

- It's a certain fact that I currently predict I'll see blue, but that's not the same fact as it being a certainty as to what my sensor will see when I look outside;

- If I look out the window and see purple-black, then in reality it was nighttime, and I will then write that it's nighttime into my RAM;

- If I write that it's nighttime into my RAM, this won't change whether it's daytime and it won't change what my sensor sees when it looks out the window.

All of these propositions can be stated without using the word 'truth' in any particular instance.

Will a sophisticated but isolated AI benefit further from having abstract concepts for 'truth' and 'falsehood' in general - an abstract concept of map-territory correspondence, apart from any particular historical cases where the AI thought it was daytime and in reality it was nighttime? If so, how?

Meditation: If we were dealing with an Artificial Intelligence that never had to interact with other intelligent beings, would it benefit from an abstract notion of 'truth'?

...

...

...

Reply: The abstract concept of 'truth' - the general idea of a map-territory correspondence - is required to express ideas such as:

- Generalized across possible maps and possible cities, if your map of a city is accurate, navigating according to that map is more likely to get you to the airport on time.

- In general, to draw a true map of a city, someone has to go out and look at the buildings; there's no way you'd end up with an accurate map by sitting in your living-room with your eyes closed trying to imagine what you wish the city would look like.

- In abstract generality: True beliefs are more likely than false beliefs to make correct experimental predictions, so if (in general) we increase our credence in hypotheses that make correct experimental predictions, then (in general) our model of reality should become incrementally more true over time.

This is the main benefit of talking and thinking about 'truth' - that we can generalize rules about how to make maps match territories in general; we can learn lessons that transfer beyond particular skies being blue.

You can sit on a chair without having an abstract, general, quoted concept of sitting; cats, for example, do this all the time. One use for having a word "Sit!" that means sitting, is to communicate to another being that you would like them to sit. But another use is to think about "sitting" up at the meta-level, abstractly, in order to design a better chair.

You don't need an abstract meta-level concept of "truths", aka map-territory correspondences, in order to look out at the sky and see purple-black and be surprised and change your mind; animals were doing that before they had words at all. You need it in order to think, at one meta-level up, about crafting improved thought processes that are better at producing truths. That, only one animal species does, and it's the one that has words for abstract things.

Next in main sequence:

Complete philosophical panic has turned out not to be justified (it never is). But there is a key practical problem that results from our internal evaluation of 'truth' being a comparison of a map of a map, to a map of reality: On this schema it is very easy for the brain to end up believing that a completely meaningless statement is 'true'.

Some literature professor lectures that the famous authors Carol, Danny, and Elaine are all 'post-utopians', which you can tell because their writings exhibit signs of 'colonial alienation'. For most college students the typical result will be that their brain's version of an object-attribute list will assign the attribute 'post-utopian' to the authors Carol, Danny, and Elaine. When the subsequent test asks for "an example of a post-utopian author", the student will write down "Elaine". What if the student writes down, "I think Elaine is not a post-utopian"? Then the professor models thusly...

...and marks the answer false.

After all...

The sentence "Elaine is a post-utopian" is true if and only if Elaine is a post-utopian.

...right?

Now of course it could be that this term does mean something (even though I made it up). It might even be that, although the professor can't give a good explicit answer to "What is post-utopianism, anyway?", you can nonetheless take many literary professors and separately show them new pieces of writing by unknown authors and they'll all independently arrive at the same answer, in which case they're clearly detecting some sensory-visible feature of the writing. We don't always know how our brains work, and we don't always know what we see, and the sky was seen as blue long before the word "blue" was invented; for a part of your brain's world-model to be meaningful doesn't require that you can explain it in words.

On the other hand, it could also be the case that the professor learned about "colonial alienation" by memorizing what to say to his professor. It could be that the only person whose brain assigned a real meaning to the word is dead. So that by the time the students are learning that "post-utopian" is the password when hit with the query "colonial alienation?", both phrases are just verbal responses to be rehearsed, nothing but an answer on a test.

The two phrases don't feel "disconnected" individually because they're connected to each other - post-utopianism has the apparent consequence of colonial alienation, and if you ask what colonial alienation implies, it means the author is probably a post-utopian. But if you draw a circle around both phrases, they don't connect to anything else. They're floating beliefs not connected with the rest of the model. And yet there's no internal alarm that goes off when this happens. Just as "being wrong feels like being right" - just as having a false belief feels the same internally as having a true belief, at least until you run an experiment - having a meaningless belief can feel just like having a meaningful belief.

(You can even have fights over completely meaningless beliefs. If someone says "Is Elaine a post-utopian?" and one group shouts "Yes!" and the other group shouts "No!", they can fight over having shouted different things; it's not necessary for the words to mean anything for the battle to get started. Heck, you could have a battle over one group shouting "Mun!" and the other shouting "Fleem!" More generally, it's important to distinguish the visible consequences of the professor-brain's quoted belief (students had better write down a certain thing on his test, or they'll be marked wrong) from the proposition that there's an unquoted state of reality (Elaine actually being a post-utopian in the territory) which has visible consquences.)

One classic response to this problem was verificationism, which held that the sentence "Elaine is a post-utopian" is meaningless if it doesn't tell us which sensory experiences we should expect to see if the sentence is true, and how those experiences differ from the case if the sentence is false.

But then suppose that I transmit a photon aimed at the void between galaxies - heading far off into space, away into the night. In an expanding universe, this photon will eventually cross the cosmological horizon where, even if the photon hit a mirror reflecting it squarely back toward Earth, the photon would never get here because the universe would expand too fast in the meanwhile. Thus, after the photon goes past a certain point, there are no experimental consequences whatsoever, ever, to the statement "The photon continues to exist, rather than blinking out of existence."

And yet it seems to me - and I hope to you as well - that the statement "The photon suddenly blinks out of existence as soon as we can't see it, violating Conservation of Energy and behaving unlike all photons we can actually see" is false, while the statement "The photon continues to exist, heading off to nowhere" is true. And this sort of question can have important policy consequences: suppose we were thinking of sending off a near-light-speed colonization vessel as far away as possible, so that it would be over the cosmological horizon before it slowed down to colonize some distant supercluster. If we thought the colonization ship would just blink out of existence before it arrived, we wouldn't bother sending it.

It is both useful and wise to ask after the sensory consequences of our beliefs. But it's not quite the fundamental definition of meaningful statements. It's an excellent hint that something might be a disconnected 'floating belief', but it's not a hard-and-fast rule.

You might next try the answer that for a statement to be meaningful, there must be some way reality can be which makes the statement true or false; and that since the universe is made of atoms, there must be some way to arrange the atoms in the universe that would make a statement true or false. E.g. to make the statement "I am in Paris" true, we would have to move the atoms comprising myself to Paris. A literateur claims that Elaine has an attribute called post-utopianism, but there's no way to translate this claim into a way to arrange the atoms in the universe so as to make the claim true, or alternatively false; so it has no truth-condition, and must be meaningless.

Indeed there are claims where, if you pause and ask, "How could a universe be arranged so as to make this claim true, or alternatively false?", you'll suddenly realize that you didn't have as strong a grasp on the claim's truth-condition as you believed. "Suffering builds character", say, or "All depressions result from bad monetary policy." These claims aren't necessarily meaningless, but they're a lot easier to say, than to visualize the universe that makes them true or false. Just like asking after sensory consequences is an important hint to meaning or meaninglessness, so is asking how to configure the universe.

But if you say there has to be some arrangement of atoms that makes a meaningful claim true or false...

Then the theory of quantum mechanics would be meaningless a priori, because there's no way to arrange atoms to make the theory of quantum mechanics true.

And when we discovered that the universe was not made of atoms, but rather quantum fields, all meaningful statements everywhere would have been revealed as false - since there'd be no atoms arranged to fulfill their truth-conditions.

Meditation: What rule could restrict our beliefs to just propositions that can be meaningful, without excluding a priori anything that could in principle be true?

- Meditation Answers - (A central comment for readers who want to try answering the above meditation (before reading whatever post in the Sequence answers it) or read contributed answers.)

- Mainstream Status - (A central comment where I say what I think the status of the post is relative to mainstream modern epistemology or other fields, and people can post summaries or excerpts of any papers they think are relevant.)

Part of the sequence Highly Advanced Epistemology 101 for Beginners

Next post: "Skill: The Map is Not the Territory"

This is a great post. I think the presentation of the ideas is clearer and more engaging than the sequences, and the cartoons are really nice. Wild applause for the artist.

I have a few things to say about the status of these ideas in mainstream philosophy, since I'm somewhat familiar with the mainstream literature (although admittedly it's not the area of my expertise). I'll split up my individual points into separate comments.

Summary of my point: Tarski's biconditionals are not supposed to be a definition of truth. They are supposed to be a test of the adequacy of a proposed definition of truth. Proponents of many different theories claim that their theory passes this test of adequacy, so to identify Tarski's criterion with the correspondence theory is incorrect, or at the very least, a highly controversial claim that requires defense. What follows is a detailed account of why the biconditionals can't be an adequate definition of truth, and of what Tarski's actual theory of truth is.

Describing Tarski's biconditionals as a definition of truth or a theory of truth is misleading. The relevant paper is The Semantic Conception of Truth. Let's call sentences of the form 'p' is true iff p T-sentences. Tarski's claim in the paper is that the T-sentences constitute a criterion of adequacy for any proposed theory of truth. Specifically, a theory of truth is only adequate if all the T-sentences follow from it. This basically amounts to the claim that any adequate theory of truth must get the extension of the truth-predicate right -- it must assign the truth-predicate to all and only those sentences that are in fact true.

I admit that the conjunction of all the T-sentences does in fact satisfy this criterion of adequacy. All the individual T-sentences do follow from this conjunction (assuming we've solved the subtle problem of dealing with infinitely long sentences). So if we are measuring by this criterion alone, I guess this conjunction would qualify as an adequate theory of truth. But there are other plausible criteria according to which it is inadequate. First, it's a frickin' infinite conjunction. We usually prefer our definitions to be shorter. More significantly, we usually demand more than mere extensional adequacy from our definitions. We also demand intensional adequacy.

If you ask someone for a definition of "Emperor of Rome" and she responds "X is an Emperor of Rome iff X is one of these..." and then proceeds to list every actual Emperor of Rome, I suspect you would find this definition inadequate. There are possible worlds in which Julius Caesar was an Emperor of Rome, even though he wasn't in the actual world. If your friend is right, then those worlds are ruled out by definition. Surely that's not satisfactory. The definition is extensionally adequate but not intensionally adequate. The T-sentence criterion only tests for extensional adequacy of a definition. It is satisfied by any theory that assigns the correct truth predicates in our world, whether or not that theory limns the account of truth in a way that is adequate for other possible worlds. Remember, the biconditionals here are material, not subjunctive. The T-sentences don't tell us that an adequate theory would assign "Snow is green" as true if snow were green. But surely we want an adequate theory to do just that. If you regard the T-sentences themselves as the definition of truth, all that the definition gives us is a scheme for determining which truth ascriptions are true and false in our world. It tells us nothing about how to make these determinations in other possible worlds.

To make the problem more explicit, suppose I speak a language in which the sentence "Snow is white" means that grass is green. It will still be true that, for my language, "Snow is white" is true iff snow is white. Yet we don't want to say this biconditional captures what it means for "Snow is white" to be true in my language. After all, in a possible world where snow remained white but grass was red, the sentence would be false.

Tarski was a smart guy, and I'm pretty sure he realized all this (or at least some of it). He constantly refers to the T-sentences as material criteria of adequacy for a definition of truth. He says (speaking about the T-sentences), "... we shall call a definition of truth 'adequate' if all these equivalences follow from it." (although this seems to ignore the fact that there are other important criteria of adequacy) When discussing a particular objection to his view late in the paper, he says, "The author of this objection mistakenly regards scheme (T)... as a definition of truth." Unfortunately, he also says stuff that might lead one to think he does think of the conjunction of all T-sentences as a definition: "We can only say that every equivalence of the form (T)... may be considered a partial definition of truth, which explains wherein the truth of this one individual sentence consists. The general definition has to be, in a certain sense, a logical conjunction of all these partial definitions."

I read the "in a certain sense" there as a subtle concession that we will need more than just a conjunction of the T-sentences for an adequate definition of truth. As support for my reading, I appeal to the fact that Tarski explicitly offers a definition of truth in his paper (in section 11), one that is more than just a conjunction of T-sentences. He defines truth in terms of satisfaction, which in turn is defined recursively using rules like: The objects a and b satisfy the sentential function "P(x, y) or Q(x, y)" iff they satisfy at least one of the functions "P(x, y)" or "Q(x, y)". His definition of truth is basically that a sentence is true iff it is satisfied by all objects and false otherwise. This works because a sentence, unlike a general sentential function, has no free variables to which objects can be bound.

This definition is clearly distinct from the logical conjunction of all T-sentences. Tarski claims it entails all the T-sentences, and therefore satisfies his criterion of adequacy. Now, I think Tarski's actual definition of truth isn't all that helpful. He defines truth in terms of satisfaction, but satisfaction is hardly a more perspicuous concept. True, he provides a recursive procedure for determining satisfaction, but this only tells us when compound sentential functions are satisfied once we know when simple ones are satisfied. His account doesn't explain what it means for a simple sentential function to be satisfied by an object. This is just left as a primitive in the theory. So, yeah, Tarski's actual theory of truth kind of sucks.

His criterion of adequacy, though, has been very influential. But it is not a theory of truth, and that is not the way it is treated by philosophers. It is used as a test of adequacy, and proponents of most theories of truth (not just the correspondence theory) claim that their theory satisfies this test. So to identify Tarski's definition/criterion/whatever with the correspondence theory misrepresents the state of play. There are, incidentally, a group of philosophers who do take the T-sentences to be a full definition of truth, or at least to be all that we can say about truth. But these are not correspondence theorists. They are deflationists.

The latest Rationally Speaking post looks relevant: Ian Pollock describes aspects of Eliezer's view as "minimalism" with a link to that same SEP article. He also mentions Simon Blackburn's book, where Blackburn describes minimalists or quietists as making the same point Eliezer makes about collapsing "X is true" to "X" and a similar point about the usefulness of the term "truth" as a generalisation (though it seems that minimalists would say that this is only a linguistic convenience, whereas Eliezer seems to have a... (read more)