My take on Leopold Aschenbrenner's new report: I think Leopold gets it right on a bunch of important counts.

Three that I especially care about:

- Full AGI and ASI soon. (I think his arguments for this have a lot of holes, but he gets the basic point that superintelligence looks 5 or 15 years off rather than 50+.)

- This technology is an overwhelmingly huge deal, and if we play our cards wrong we're all dead.

- Current developers are indeed fundamentally unserious about the core risks, and need to make IP security and closure a top priority.

I especially appreciate that the report seems to get it when it comes to our basic strategic situation: it gets that we may only be a few years away from a truly world-threatening technology, and it speaks very candidly about the implications of this, rather than soft-pedaling it to the degree that public writings on this topic almost always do. I think that's a valuable contribution all on its own.

Crucially, however, I think Leopold gets the wrong answer on the question "is alignment tractable?". That is: OK, we're on track to build vastly smarter-than-human AI systems in the next decade or two. How realistic is it to think that we can control such systems?

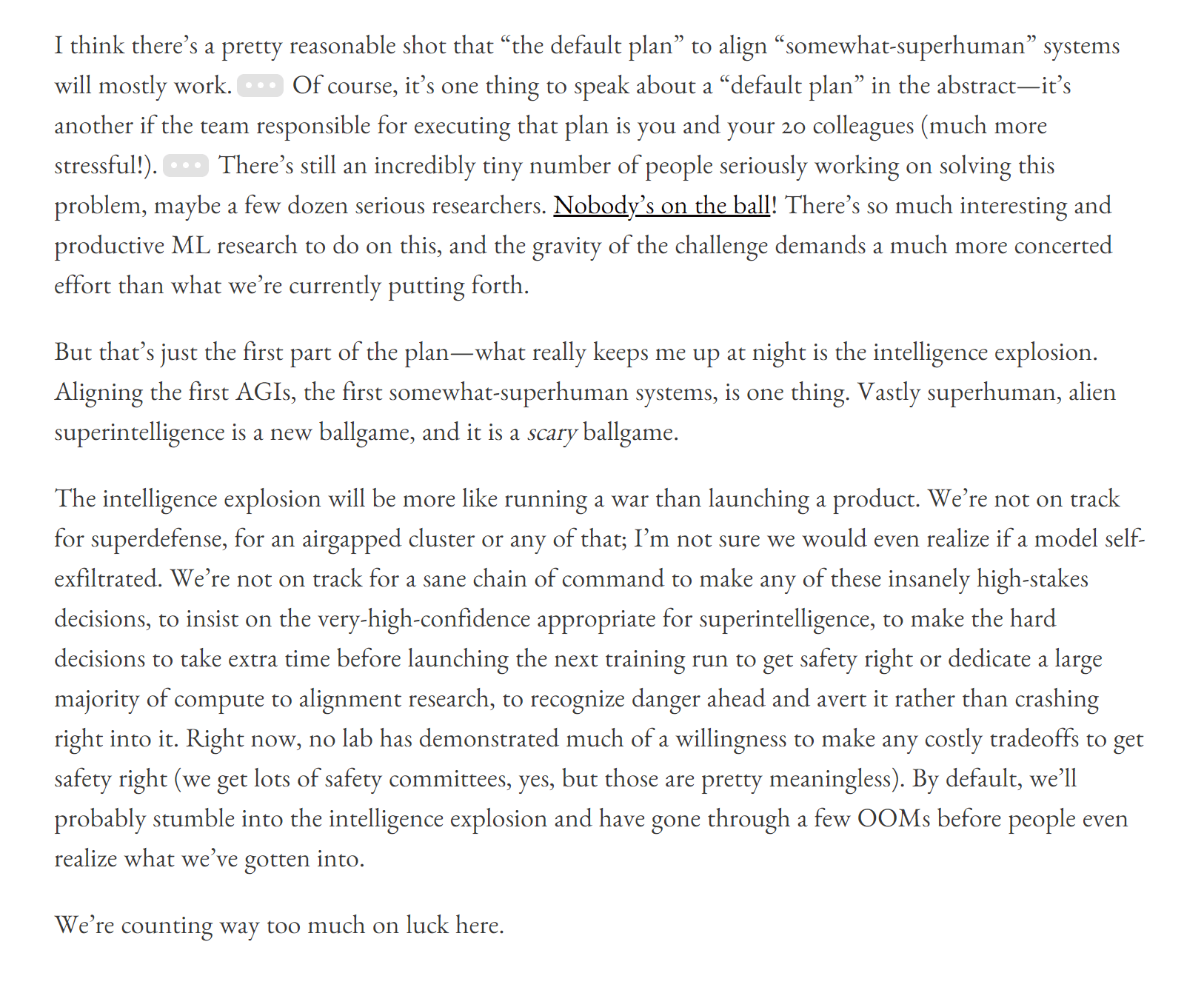

Leopold acknowledges that we currently only have guesswork and half-baked ideas on the technical side, that this field is extremely young, that many aspects of the problem look impossibly difficult (see attached image), and that there's a strong chance of this research operation getting us all killed. "To be clear, given the stakes, I think 'muddling through' is in some sense a terrible plan. But it might be all we’ve got." Controllable superintelligent AI is a far more speculative idea at this point than superintelligent AI itself.

I think this report is drastically mischaracterizing the situation. ‘This is an awesome exciting technology, let's race to build it so we can reap the benefits and triumph over our enemies’ is an appealing narrative, but it requires the facts on the ground to shake out very differently than how the field's trajectory currently looks.

The more normal outcome, if the field continues as it has been, is: if anyone builds it, everyone dies.

This is not a national security issue of the form ‘exciting new tech that can give a country an economic or military advantage’; it's a national security issue of the form ‘we've found a way to build a doomsday device, and as soon as anyone starts building it the clock is ticking on how long before they make a fatal error and take themselves out, and take the rest of the world out with them’.

Someday superintelligence could indeed become more than a doomsday device, but that's the sort of thing that looks like a realistic prospect if ASI is 50 or 150 years away and we fundamentally know what we're doing on a technical level — not if it's more like 5 or 15 years away, as Leopold and I agree.

The field is not ready, and it's not going to suddenly become ready tomorrow. We need urgent and decisive action, but to indefinitely globally halt progress toward this technology that threatens our lives and our children's lives, not to accelerate ourselves straight off a cliff.

Concretely, the kinds of steps we need to see ASAP from the USG are:

- Spearhead an international alliance to prohibit the development of smarter-than-human AI until we’re in a radically different position. The three top-cited scientists in AI (Hinton, Bengio, and Sutskever) and the three leading labs (Anthropic, OpenAI, and DeepMind) have all publicly stated that this technology's trajectory poses a serious risk of causing human extinction (in the CAIS statement). It is absurd on its face to let any private company or nation unilaterally impose such a risk on the world; rather than twiddling our thumbs, we should act.

- Insofar as some key stakeholders aren’t convinced that we need to shut this down at the international level immediately, a sane first step would be to restrict frontier AI development to a limited number of compute clusters, and place those clusters under a uniform monitoring regime to forbid catastrophically dangerous uses. Offer symmetrical treatment to signatory countries, and do not permit exceptions for any governments. The idea here isn’t to centralize AGI development at the national or international level, but rather to make it possible at all to shut down development at the international level once enough stakeholders recognize that moving forward would result in self-destruction. In advance of a decision to shut down, it may be that anyone is able to rent H100s from one of the few central clusters, and then freely set up a local instance of a free model and fine-tune it; but we retain the ability to change course, rather than just resigning ourselves to death in any scenario where ASI alignment isn’t feasible.

Rapid action is called for, but it needs to be based on the realities of our situation, rather than trying to force AGI into the old playbook of far less dangerous technologies. The fact that we can build something doesn't mean that we ought to, nor does it mean that the international order is helpless to intervene.

I think most advocacy around international coordination (that I've seen, at least) has this sort of vibe to it. The claim is "unless we can make this work, everyone will die."

I think this is an important point to be raising– and in particular I think that efforts to raise awareness about misalignment + loss of control failure modes would be very useful. Many policymakers have only or primarily heard about misuse risks and CBRN threats, and the "policymaker prior" is usually to think "if there is a dangerous, tech the most important thing to do is to make the US gets it first."

But in addition to this, I'd like to see more "international coordination advocates" come up with concrete proposals for what international coordination would actually look like. If the USG "wakes up", I think we will very quickly see that a lot of policymakers + natsec folks will be willing to entertain ambitious proposals.

By default, I expect a lot of people will agree that international coordination in principle would be safer but they will fear that in practice it is not going to work. As a rough analogy, I don't think most serious natsec people were like "yes, of course the thing we should do is enter into an arms race with the Soviet Union. This is the safeest thing for humanity."

Rather, I think it was much more a vibe of "it would be ideal if we could all avoid an arms race, but there's no way we can trust the Soviets to follow-through on this." (In addition to stuff that's more vibesy and less rational than this, but I do think insofar as logic and explicit reasoning were influential, this was likely one of the core cruses.)

In my opinion, one of the most important products for "international coordination advocates" to produce is some sort of concrete plan for The International Project. And importantly, it would need to somehow find institutional designs and governance mechanisms that would appeal to both the US and China. Answering questions like "how do the international institutions work", "who runs them", "how are they financed", and "what happens if the US and China disagree" will be essential here.

The Baruch Plan and the Acheson-Lilienthal Report (see full report here) might be useful sources of inspiration.

P.S. I might personally spend some time on this and find others who might be interested. Feel free to reach out if you're interested and feel like you have the skillset for this kind of thing.

From a Realpolitique point of view, if the Chinese were working on a technology that has an ~X% chance of killing everyone, and ~99-X% chance of permanently locking in the rule of the CCP over all of humanity (even if X is debatable), and this is a technology which requires a very large O($1T) datacenter for months, then the obvious response from the rest of the world to China is "Stop, verifiably, before we blow up your datacenter".