[This article was originally published on Dan Elton's blog, More is Different.]

Cerebrolysin is an unregulated medical product made from enzymatically digested pig brain tissue. Hundreds of scientific papers claim that it boosts BDNF, stimulates neurogenesis, and can help treat numerous neural diseases. It is widely used by doctors around the world, especially in Russia and China.

A recent video of Bryan Johnson injecting Cerebrolysin has over a million views on X and 570,000 views on YouTube. The drug, which is advertised as a “peptide combination”, can be purchased easily online and appears to be growing in popularity among biohackers, rationalists, and transhumanists. The subreddit r/Cerebrolysin has 3,100 members.

TL;DR

Unfortunately, our investigation indicates that the benefits attributed to Cerebrolysin are biologically implausible and unlikely to be real. Here’s what we found:

- Cerebrolysin has been used clinically since the 1950s, and has escaped regulatory oversight due to some combination of being a “natural product” and being grandfathered in.

- Basic information that would be required for any FDA approved drug is missing, including information on the drug’s synthesis, composition, and pharmacokinetics.

- Ever Pharma’s claim that it contains neurotrophic peptides in therapeutic quantities is likely false. HPLC and other evidence show Cerebrolysin is composed of amino acids, phosphates, and salt, along with some random protein fragments.

- Ever Pharma’s marketing materials for Cerebrolysin contain numerous scientific errors.

- Many scientific papers on Cerebrolysin appear to have ties to its manufacturer, Ever Pharma, and sometimes those ties are not reported.

- Ever Pharma’s explanation of how the putative peptides in Cerebrolyin cross the blood-brain barrier does not make sense and flies in the face of scientific research which shows that most peptides do not cross the blood-brain barrier (including neurotrophic peptides like BDNF, CDNF, and GDNF).

- Since neurotrophic factors are the proposed mechanism for Cerebrolysin’s action, it is reasonable to doubt claims of Cerebrolysin’s efficacy. Most scientific research is false. It may have a mild therapeutic effect in some contexts, but the research on this is shaky. It is likely safe to inject in small quantities, but is almost certainly a waste of money for anyone looking to improve their cognitive function.

Introduction

One of us (Dan) was recently exposed to Cerebrolysin at the Manifest conference in Berkeley, where a speaker spoke very highly about it and even passed around ampoules of it for the audience to inspect.

Dan then searched for Cerebrolysin on X and found a video by Bryan Johnson from May 23 that shows him injecting Cerebrolysin. Johnson describes it as a “new longevity therapy” that “fosters neuronal growth and repair which may improve memory.”

Dan sent the video to Greg Fitzgerald, who is a 6th year neuroscience Ph.D. student at SUNY Albany. Greg is well-versed on the use of neurotrophic peptides for treating CNS disorders and was immediately skeptical and surprised he had not heard of it before. After Greg researched it, he felt a professional responsibility to write up his findings. He sent his writeup to Dan, who then extensively edited and expanded it.

Our critique covers three major topics: (1) sketchy marketing practices, (2) shoddy evidence base, and (3) implausible biological claims. But first, it’s interesting to understand the history of this strange substance.

The long history of Cerebrolysin

To our knowledge, the “secret history” of Cerebrolysin has not been illuminated anywhere to date.

Cerebrolysin was invented by the Austrian psychiatrist and neurologist Gerhart Harrer (1917 - 2011), who started using it in his practice around 1951. Between 1954 and 1990 he published at least ten articles on it. In a 1954 article, he describes Cerebrolysin as an “amino acid mixture containing all biologically important amino acids, including glutamic acid.” He describes how the aqueous injection used in his studies contains about 1 g worth of amino acids that are created by lysing pig brain tissue. In a 1959 paper, Harrer describes a paper chromatographic analysis he conducted, which showed the presence of 18 amino acids. He says that when dried, the substance is 57% amino acids by weight, with the rest being phosphates and inorganic salts.

It seems Harrer believed that pure amino acids have considerable therapeutic potential when given intravenously, but that the relative proportions of those amino acids should be tuned to treat different tissues. Thus, to heal brain tissue he decided to derive amino acids from pig brain tissue. Pigs were a fortuitous choice due to the fact that they are especially resistant to prion disease.

Today we know this reasoning is flawed. Your cells precisely regulate the uptake of amino acids by regulating amino acid transporters. So as long as sufficient quantities of each amino acid are ingested, cells are smart enough to take in the quantities they need.

This picture of Cerebrolysin as an amino acid mixture is consistent with marketing materials from that time. For instance, in a 1959 issue of “American Professional Pharmacist” it was described as an “amino acid combination”:

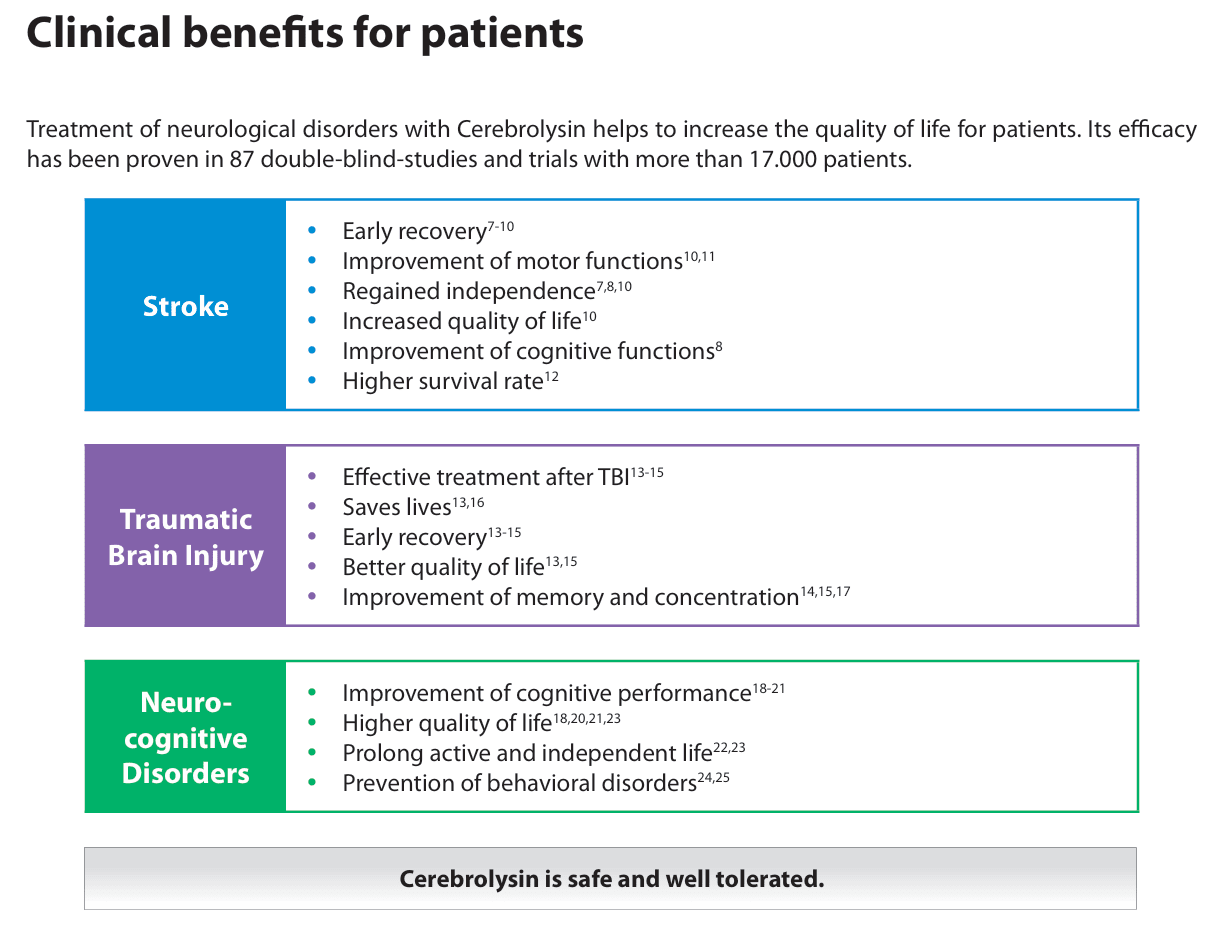

From what we can tell, the drug has been used for ischemic stroke patients since the 1970s. Hundreds of scientific papers on Cerebrolysin were published between 1990 and the present day. Papers can be found arguing that Cerebrolysin is helpful for treating traumatic brain injury, stroke, diabetes, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, dementia, seizures, diabetic neuropathy, PTSD, delirium, subarachnoid hemorrhage, closed head injury, nerve injury, facial paralysis, depression, multiple sclerosis, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

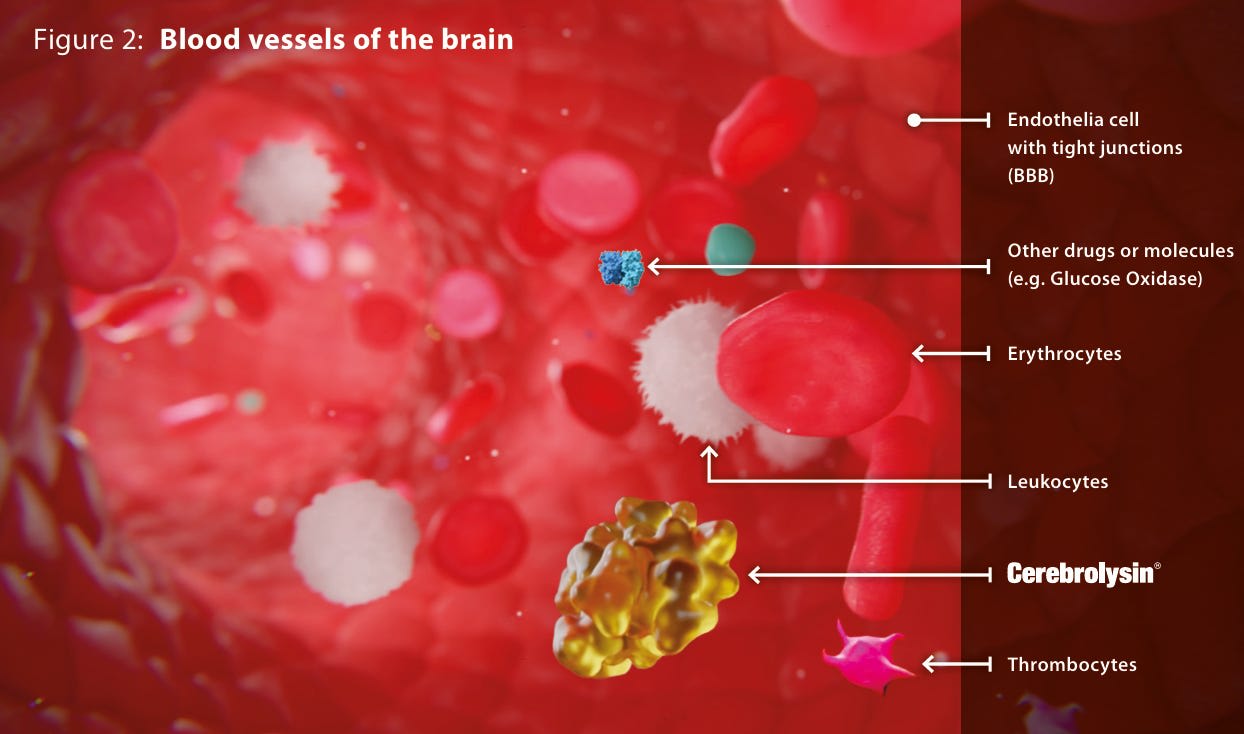

For some reason, interest in Cerebrolysin increased dramatically after 2014. This may be due to an advertising campaign by Ever Pharma, including the creation of cerebrolysin.com in 2017.

Today, Ever Pharma has business operations in thirteen countries[1] and claims that Cerebrolysin is used in over 50 countries. While this may be true, it is primarily used in Russia, China, and several post-Soviet countries.

As we mentioned, Cerebrolysin is now widely used “off-label” by biohackers and longevity enthusiasts.

Cerebrolysin.com is full of scientific errors

At first glance, the Cerebrolysin website appears very professional, with many polished diagrams showing how Cerebrolysin works. A closer look however shows scientific sloppiness that is far from professional. For example, consider this figure:

We noticed a few odd things about this figure alone. First, glucose oxidase is an intracellular protein that would never be in the bloodstream under normal circumstances. It is misleading to show Cerebrolysin as larger than glucose oxidase, since the putative peptides in Cerebrolysin are described as being around 10 kDa while glucose oxidase is 180 kDa. Closer inspection shows this is a 3D graphic where the Cerebrolysin molecule is meant to be closer to the viewer. As such, the relative size of each molecule is impossible to judge. This sort of 3D graphic is deliberately avoided in scientific papers.

Of course, many FDA-approved drugs also have deceptive marketing. There are examples of drug companies persuading doctors to prescribe off-label, drug commercials that exaggerate expected benefits, and drug companies manipulating the FDA approval process. Similarly, the FDA is sometimes too hesitant to authorize the sale of experimental drugs out of a misplaced concern about patients being exploited. Despite all these problems with our medical system in the US, the level of deception used by Ever Pharma in marketing Cerebrolysin is worse than anything we’ve seen for an FDA-approved drug.

The Cerebrolysin website should be contrasted with the website of any FDA-approved drug. As an example, let's look at the website for the recently approved Alzheimer's drug, Aduhelm (aducanumab). The process of navigating pertinent information is pretty straightforward. With three clicks one can navigate to the clinical trial results that led to the drug's approval. One can find preclinical results about BBB permeability, detailed rationales for the doses chosen for the final product, and a complete description of the aducanumab molecule and the other constituents of the drug. With a little extra searching, you can even find some details about the quality assurance that goes into ensuring that every batch of drug is uniform.

Medicine websites are always partly marketing, but we feel Cerebrolysin.com is pure marketing. Regardless of how you feel about the FDA, it is good that there are laws preventing drug companies from directly advertising their products with specious claims.

To show what we mean about specious claims, let’s take a look at this chart:

These are wild claims. You will not find any FDA-approved drug with so many claims, for the simple reason that it would be near-impossible to substantiate all of them.

We encourage readers to dig into the references provided to Ever Pharma to see if they actually substantiate the claims in question — in our opinion they largely do not (we will give some examples in the next section).

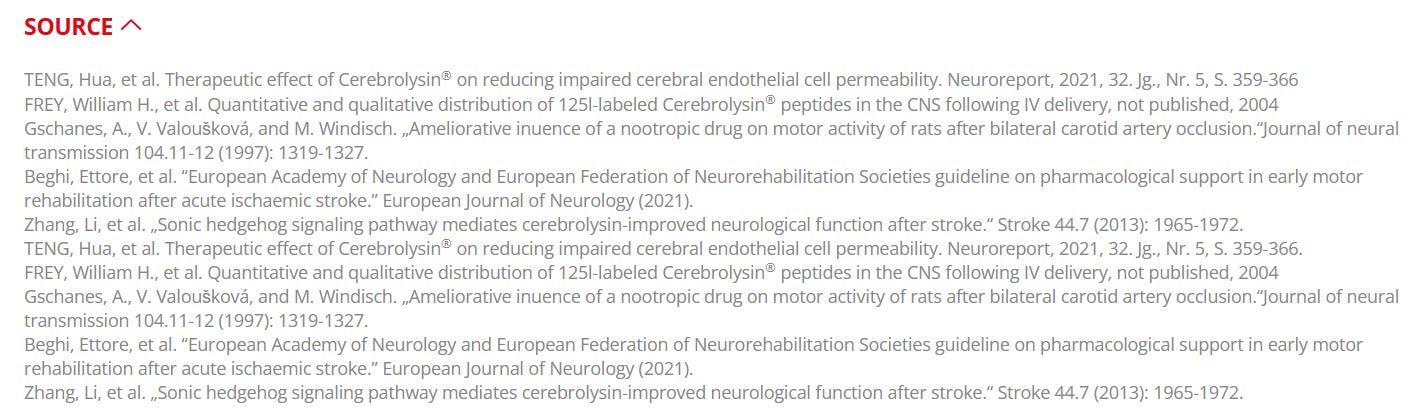

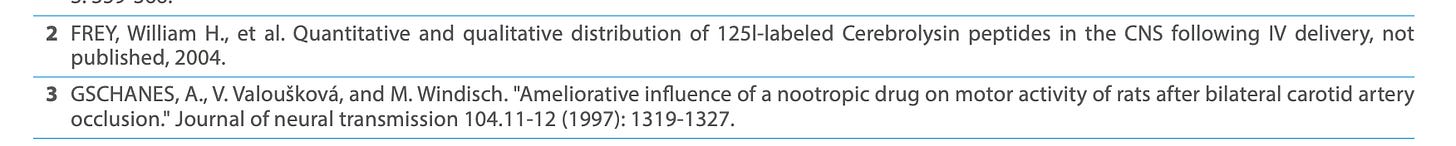

An example of Ever Pharma’s sloppy citation practices can be seen in the "Mode of Action" page:

What appears to be eight citations is actually just four citations, duplicated. The citations aren't in a uniform style, suggesting they've been copied-and-pasted from other places. One of the key citations, (Frey, 2004), was never published, and isn't available anywhere online (nor could we obtain it from Dr. Frey or Ever Pharma). Furthermore, these citations are not attached to specific claims in the text. We are asked to believe that the dozens of claims made in the text are substantiated by just these four sources.

If one were to be maximally charitable, one might say that all the webpages fall under the auspices of 'marketing', and to judge them as we would a journal article amounts to a category error.

However, the Cerebrolysin website acts as if it is a repository of scientific knowledge. For instance, it contains a "monograph”, which is presented as a technical resource, and shorter documents that are said to summarize the findings of “rigorous clinical trials”.

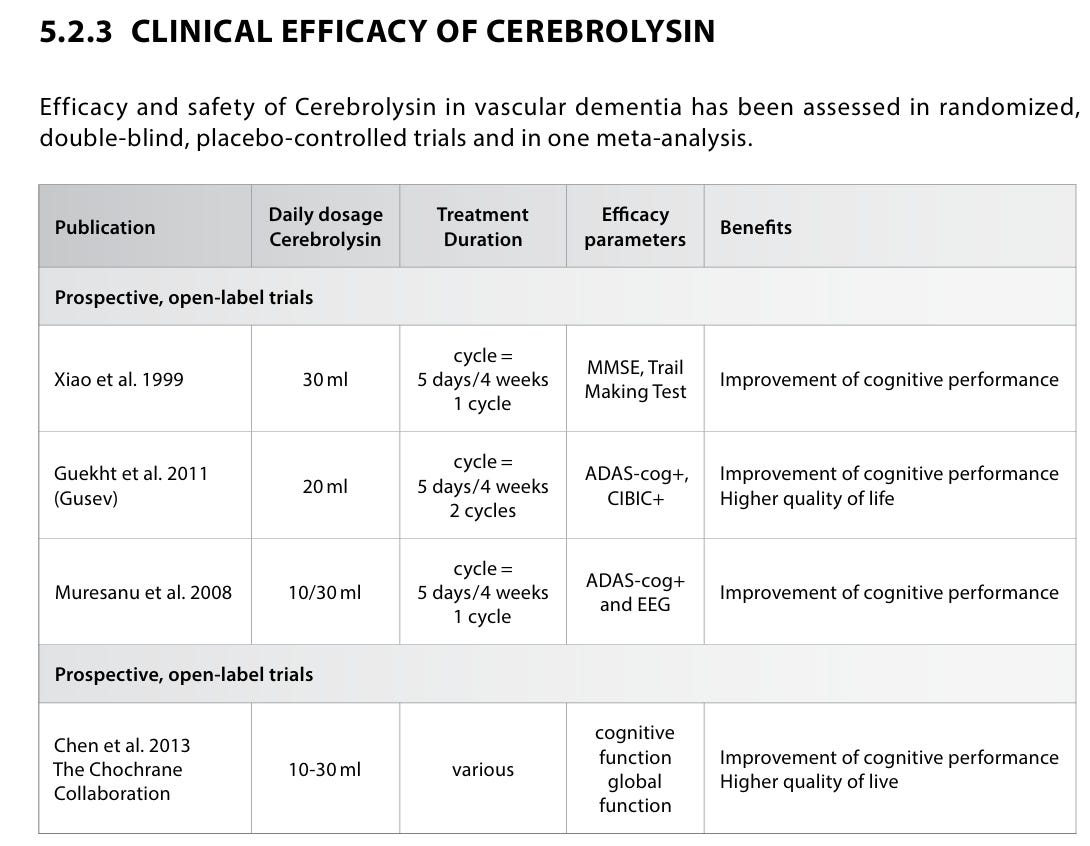

We found that the “monograph” is little better than the other materials on the website. For instance, consider this table:

Above the chart there is a claim about "double-blind, placebo-controlled trials", but within the chart, none of the cited studies meet this description. Nor is this problem limited to this one chart -- similar false claims about trials can be found throughout this document.

This same chart contains another deception: the study in the lowest row of the chart is actually a systematic review, not a meta-analysis as the chart description claims. The chart summarizes that article as providing evidence of "improvement of cognitive performance. Higher quality of live [sic]." Now let's compare that to the actual text of the article:

“Authors' conclusions: Cerebrolysin may have positive effects on cognitive function and global function in elderly patients with vascular dementia of mild to moderate severity, but there is still insufficient evidence to recommend Cerebrolysin as a routine treatment for vascular dementia due to the limited number of included trials, wide variety of treatment durations and short‐term follow‐up in most of the trials.”

If the writers of the Cerebrolysin monograph are so willing to blatantly misrepresent the sources they're using as evidence, it ought to make us highly skeptical of everything they have to say.

The evidence base for Cerebrolysin contains conflicts of interest and a statistically improbable rate of success

Perhaps you have read all this and say, “who cares about these issues with the website and monograph?” On some level, the contents of the website have no relation to the actual efficacy of Cerebrolysin, which Ever Pharma claims "has been proven in 87 double-blind-studies and trials with more than 17,000 patients."

Since hundreds of articles have been published on Cerebrolysin, I (Greg) decided to look at the top 10 most-cited articles on Google Scholar that contained the terms "Cerebrolysin" + "double-blind". Presumably, these 10 articles are representative of all the double-blind studies of Cerebrolysin. If anything, their quality may be better than average since they earned more citations and a higher search ranking.

The most apparent problem with these articles is the conflicts of interest. Nine of the top ten articles on the first page of results have authors who are affiliated with Ever Pharma (or its former name, EBEWE Pharma), and therefore have a financial stake in Cerebrolysin being shown to be effective.[2]

In one of these articles, we are provided with the following comment:

Co-authors HM and ED are employees of EBEWE Pharma. Both have no ownership in the company, and their compensation is not linked to the outcome of research projects. (Alvarez et al, 2011)

This isn’t very reassuring — working for the company that manufactures Cerebrolysin certainly seems to give them a stake in the outcome of any research project they might be involved in.

I (Greg) went through the next several pages of Google Scholar results in an attempt to find a single publication that tested Cerebrolysin that found a null result. There were none. This degree of uniform success is statistically implausible, especially given the comparatively small sample sizes used in all of those studies. If you look up clinical trials of Alzheimer's disease drugs like donepezil and galantamine, you will find some trials that failed to observe any benefit. Given random sampling and small effect sizes, the absence of any trials with null results is very suspicious.

Another concerning feature of the evidence base for Cerebrolysin is the absence of pre-registration. For those unfamiliar, when you do a federally-funded clinical trial in the US you are required to preregister on clinicaltrials.gov. You need to specify your methods, your method of recruiting patients, and other relevant information. The EU has a similar system for pre-registering clinical trials.

Despite hundreds of papers on Cerebrolysin, a search for Cerebrolysin on the EU Clinical Trials Register returns only five results.

In most published clinical trials on Cerebrolysin, basic questions like "what country were these trials conducted in?" are not addressed. It appears that a large number were done at Russian State Medical University. In the Russian clinical trial database there are only two reported trials for Cerebrolysin — in 2013 (completed) and 2015 (suspended).

Another disturbing pattern we noticed is that most of the review articles about Cerebrolysin have the same set of authors, with their accompanying conflicts of interest. One of the most-cited reviews, Plosker & Gauthier (2009) fails to disclose an important relationship between one of their authors and Ever Pharma. An article from the same year makes clear that “Gauthier is a member of the EVER scientific advisory board.”

We could find only a few articles written on Cerebrolysin that are completely independent from Ever Phara. Three of those are Cochrane reviews, from 2019, 2020, and 2023. Those reviews found there is insufficient evidence to conclude that Cerebrolysin is effective in treating either ischemic stroke or vascular dementia. Somewhat disturbingly, the 2020 review notes a higher rate of severe side effects among the patients given Cerebrolysin across several trials, although there was no difference when it came to mortality or mild side effects.

So WTH is Cerebrolysin?

Greg had a lot of questions when looking at Ever Pharma’s materials. What species of pig are used? How old are those pigs? How are the pigs sourced? How are they killed? What parts of the brain do they grind up? What are the active ingredients in Cerebrolysin? What assays have been done to measure the concentration and bioactivity of the active ingredients? Is there batch-to-batch variation? How were the recommended doses chosen for Cerebrolysin? Why is it recommended that Cerebrolysin is cycled for some diseases but not others? What ingredients penetrate the blood-brain barrier?

Across several sources, Cerebrolysin is said to be "standardized". However we could not find any description of this “standardized” procedure.

Here’s what we could find:

One source says that Cerebrolysin contains "young pig brain". We could find no information on how the pig brain matter is obtained. The most economical option would be pigs slaughtered for meat. However, proteins begin deteriorating immediately upon death, so the freshness of the samples is an important issue.

The pig brain matter is ground up and hydrolyzed with enzymes. In biochemistry, hydrolysis is a type of reaction that cleaves organic molecules into smaller components. For instance, a protein is hydrolyzed into multiple, smaller polypeptide fragments. If you allow the hydrolysis to run long enough, those polypeptides will be hydrolyzed into individual amino acids.

The enzymes used are likely peptidases, because Cerebrolysin's label mentions sodium hydroxide among its inactive ingredients. The only reason sodium hydroxide would be in the drug is as a means of halting enzymatic degradation. Peptidases only function in acidic environments, so adding a strong base like sodium hydroxide is a common way to halt the degradation procedure.

After being hydrolyzed the resulting “lysate” is centrifuged to remove all insoluble components.

According to the marketing materials, Cerbrolysin contains “neurotrophic factors”. However, as we discussed earlier, between 1950 - ~1990 Cerebrolysin was described as a mixture of amino acids with some residual peptide fragments. It’s been described a bit differently over the years:

- Trojanova et al. (1976) describe Cerebrolysin as amino acids, “aligopeptides” [sic] and nucleotides.

- Kofler et al. (1990) describe Cerebrolysin as a “hydrolysate containing free amino acids (about 85%) as well as low-molecular protein-free amino acid sequences (about 15%)."

- Hartbauer et al. (2001) describe Cerebrolysin as “approximately 25% low molecular weight peptides (10 kDA) and a mixture of approximately 75% free amino acids, based on the total nitrogen content.”[3]

Taken together, these descriptions indicate that the Cerebrolysin is ~75% amino acids, with the other ~25% being short polypeptide sequences that are the remnants of once-intact proteins that have been enzymatically degraded. Kofler et al. (1990) and Hartbauer et al. (2001) don’t provide any explanation for their ratios but their similarity and specificity are noteworthy. We suspect that these ratios were provided by Ever Pharma.

Based on our research, there seems to have been a transition in Cerebrolysin’s marketing from “amino acids” to “neurotrophic peptides” that occured in the 1980s. Yet, we could find nothing to suggest that the company updated their tissue preparation procedures in that time period.

While an enzymatic degradation procedure is compatible with the goal of producing amino acids or small peptide fragments, it is incompatible with the goal of producing neurotrophic proteins. This is because any peptide fragments would not retain their neurotrophic properties.[4]

Now, there are well-established techniques for measuring the concentration of neurotrophic factors in biological samples. There are even services that will perform the assays for you if you send them your samples. The fact there is no succinct summary of all the neurotrophic factors in Cerebrolysin and their concentrations is mind-bending.

It’s also worth taking a step back to ask if it’s reasonable to begin with that a lysate of pig brain tissue would contain an appreciable amount of neurotrophic factors. Neurotrophic proteins account for a miniscule proportion of total brain proteins, and Cerebrolysin is further diluted in water. Nowhere is any enrichment step described, and no such enrichment techniques existed when Cerebrolysin was invented in the mid 1950s.

All of our skepticism about the constituents of Cerebrolysin could all be immediately resolved if the manufacturers just performed an ELISA assay on their product, and posted the result.

Let’s drill down on Hartbauer et al.’s claim that Cerebrolysin contains 25% “~10 kDa” peptides, because it widely cited, and is cited in Ever Pharma’s marketing materials. Here are the sizes of several neurotrophic factors: NGF, 26.5 kDa; BDNF: 27.8 KDa; PDGF: 32 kDa. This would imply that whatever neurotrophic factors existed in the pig brain tissue have been reduced to fragments about half the size. In general, proteins do not retain their signaling potential after so much of their structure has been removed, although some have suggested this is the case with Cerebrolysin.

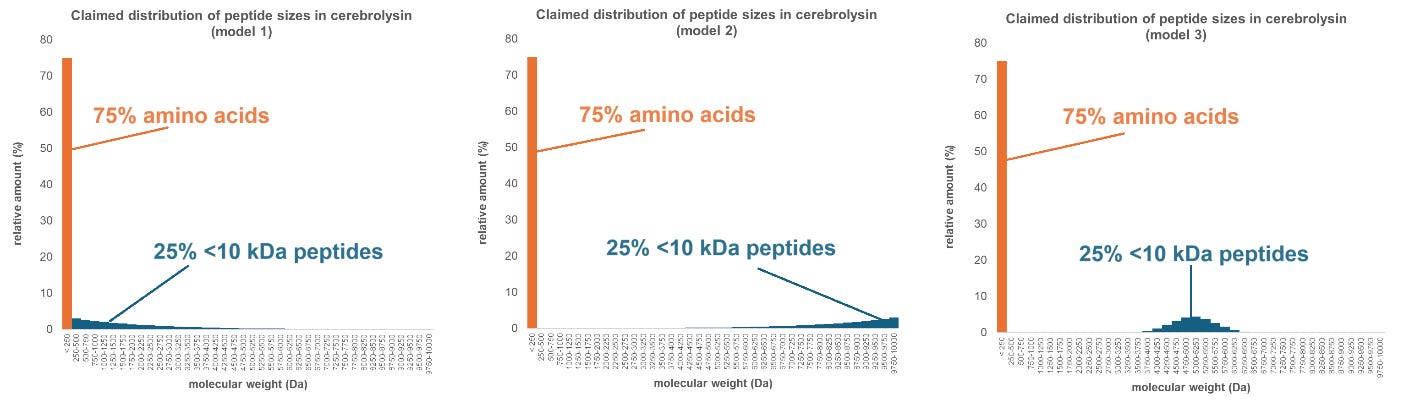

Now, we contend that there is no lysing method that would produce a solution of 75% amino acids and 25% ~10 kDa peptide fragments. Haurtbauer et al. likely meant to say “25% < 10 kDa peptides” not “25% ~ 10kDa peptides”. In fact, this is how a different paper quotes them.

Consider three distributions consisting of amino acids and < 10 kDa peptides:

Of these models, only Model 1 is consistent with lysing. Model 3 is only plausible if one mixed two different solutions, each of which underwent a different synthesis procedure.[5]

This discussion about the likely distribution of peptide sizes in Cerebrolysin is obviously significant, since if most peptide fragments are way smaller than 10 kDa, then the claim about it having neurotrophic properties is very unlikely.

We only found one study giving evidence of neurotrophic factors in Cerebrolysin, and it’s kinda sus

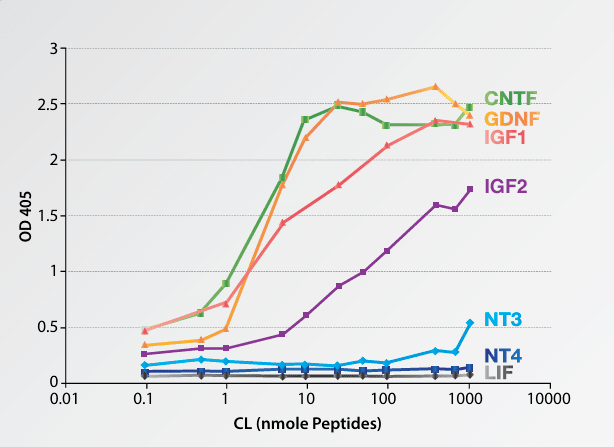

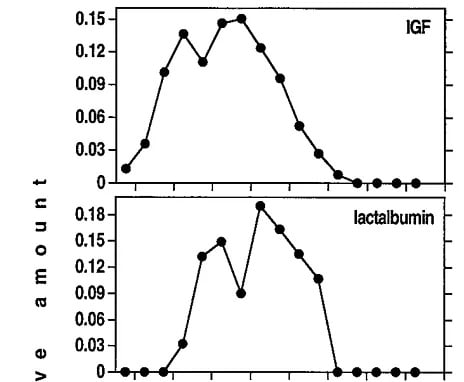

This figure from Chen et al (2007) is the only direct evidence we could find of neurotrophic factors in Cerebrolysin.

Of course, this figure is displayed prominently in Ever Pharma’s materials. The figure shows the outcome of an ELISA immunoreactivity assay for seven neurotrophic factors. We wonder why the authors did not include the two best-known neurotrophic factors, BDNF and NGF.

The y-axis (OD 405) refers to the optical density at 405 nm, and it is a proxy for concentration. The x-axis shows different dilutions of Cerebrolysin (CL), from 0.1 to 1040 nmol/µL, where the authors say that “1040 corresponds to the undiluted drug.”

At the end of the day, all this assay shows is that something in Cerebrolysin has immunoreactivity with the antibodies in the assay. This is not slam-dunk evidence that those proteins are actually present in Cerebrolysin, much less at a therapeutic concentrations.

We are both perplexed by the metric “nmol peptides” used to quantify the x-axis. Since Cerebrolysin is a mixture of many peptides, using molarity as a measurement is meaningless, unless you know the precise breakdown of the constituents. (For those who don't know, in order to measure how many moles something is, you need to know its molecular weight.) In the figure caption, the authors write: "[Cerebrolysin] was diluted from 1040 (undiluted) to 0.1 nmol peptides/50 µL." Neither of us can figure out where out where the number 1040 comes from.

HPLC-mass spectroscopy of Cerebrolysin fails to show any neurotrophic peptides

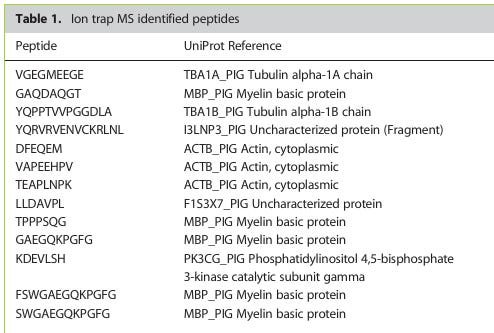

We are giving Gevaert et al. (2015) its own section. It’s an extremely important work because it’s the only paper that does HPLC-mass spectroscopy to characterize all the constituents of Cerebrolysin. It’s a true tour-de-force. Their methods are far more sophisticated than typical HPLC-mass spectroscopy study, allowing for separation of small peptide fragments. This allowed them to sequence these fragments and detect any matches with known proteins (e.g. neurotrophic factors). Regarding the observed size of the peptides:

The peptide length ranges from 6 to 15 amino acids, with an average length of 9.2 amino acids; the peptide mass ranges from 682.34 Da to 1889.05 Da, with an average mass of 1015.89 Da.

This observation is closest to Model 1 from the previous section. Of the peptide fragments that were long enough to match with an existing sequence, "no fragments of known nootropic proteins were identified".

Not surprisingly, the fragments they found come from the most abundant proteins found in the brain, such as cytoskeletal proteins (actin, tubulin) and myelin basic protein:

This is what one would predict to see from a random sampling of brain proteins. Neurotrophic factors account for only a miniscule fraction of all brain proteins, and there’s no reason to suppose they’d be especially resistant to enzymatic degradation.

Storage instructions are incongruent with peptides and there is no immune response

The storage instructions for Cerebrolysin are unrealistic for a product that is alleged to actually contain neurotrophic peptides. We are instructed to store Cerebrolysin at "room temperature not exceeding 25°C."

Greg has worked with brain lysates and dissolved preparations of neurotrophic factors in a lab. Until shown otherwise, the background assumption for peptides in aqueous solution is that they will degrade in a few days. Refrigeration can extend this to a few weeks at most. Moreover, carrier proteins are often required to prevent peptides from sticking to the glass or plastic container in which it's been stored. There is no indication that any such carrier proteins are added to Cerebrolysin.

Considering all the steps taken in biology labs to preserve the peptides in their samples, the burden is on Ever Pharma to justify their claims about having found a method to ensure the stability of dissolved peptides at room temperature.

Another piece of indirect evidence that Cerebrolysin probably contains only trace amounts of any intact proteins is the fact that injecting it doesn't provoke an immune response. Ordinarily, if you inject proteins from another species into your blood, your immune system will attack those proteins and you'll experience a systemic immune reaction. Since Cerebrolysin doesn't cause this kind of reaction, it's likely because it contains very few intact proteins. Gusev & Skvortsova (2003) discuss this, noting

Brain-specific peptides are the active fraction of the drug. Their low molecular weight avoids the possibility of anaphylaxis.

However, this explanation doesn't make sense, since the immune system is perfectly able to recognize and react to ~10 kDa proteins. Back when pig insulin (5.8 kDa) was used to treat Type 1 diabetes, a systemic immune response was a common side effect:

As they were not of human origin, bovine and porcine insulins elicited immune responses that either made their administration unpredictable or in some cases led to hypersensitivity reactions.

The putative active ingredients are unlikely to cross the blood-brain barrier

It is well-established that exogenous BDNF and CDNF cannot penetrate the blood-brain barrier. Here’s what Ever Pharma says:

“Brain-specific peptides are the active fraction of the drug. Their low molecular weight ... allows easy permeation of peptides through the BBB and their active involvement in the metabolism of brain neurons [138, 263]. (Gusev & Skvortsova 2003)”

The website cites two articles to substantiate the claim that Cerebrolysin crosses the blood-brain barrier:

Gschanes et al. (1997) doesn't come close to substantiating this claim. It is an inappropriate inference based on an observed biological effect in a rat model of ischemic stroke. There are alternative mechanisms for improved stroke recovery that don't involve blood-to-brain transport of Cerebrolysin. Somewhat disturbingly, the rats in the study who received Cerebrolysin but didn't have the experimentally-induced strokes had worse cognitive performance than the rats who received the placebo treatment.[6]

As far as Frey et al. (2004), we emailed both Ever Pharma and Dr. Frey yet failed to secure a copy. Dr. Frey told us that he does recall working with Ever Pharma (EBEWE) around that time, and he described how they may have done some work separating out the amino acids from the other components, however he said he was not directly working in the lab at that time.

Amusingly, Dr. Frey has argued elsewhere that blood-to-brain transport is not a feasible approach to delivering neurotrophic peptides to the brain. Here is a quote from a 2010 article co-authored by Frey:

Part of the problem is that these large neurotrophic protein molecules to the CNS do not efficiently cross the blood–barrier into the CNS (Poduslo & Curran, 1996; Thorne & Frey, 2001). Clinical trials have demonstrated that systemic delivery at doses that are sufficiently high to result in therapeutic levels within the CNS parenchyma also result in significant systemic side-effects (Thoenen & Sendtner, 2002). These studies suggest the need for alternative methods of drug delivery to realize the clinical promise of these neuroprotective factors.

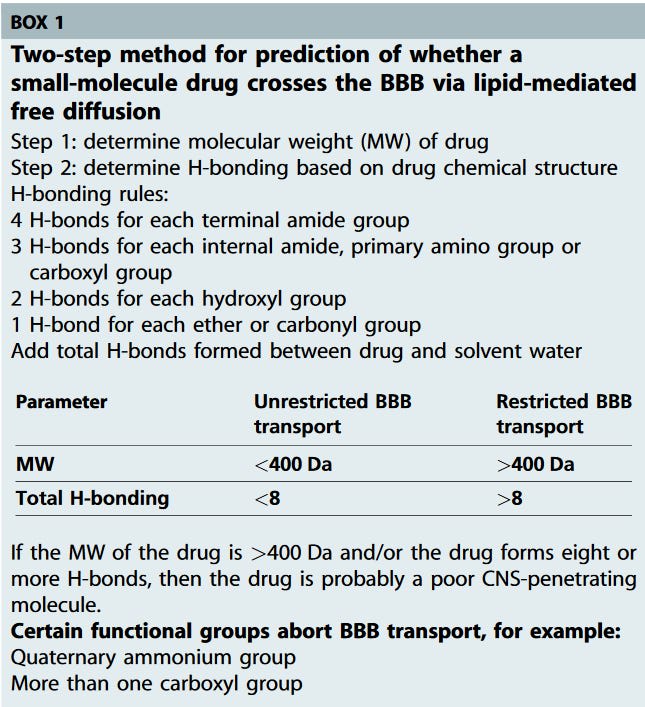

Here is a representative opinion about the role of the BBB in restricting drug delivery to the brain:

The most important factor limiting the development of new drugs for the central nervous system (CNS) is the blood–brain barrier (BBB). The BBB limits the brain penetration of most CNS drug candidates.... Radiolabeled histamine, a small molecule of just 111 Da, was injected intravenously into an adult mouse, and the animal was killed 30 mins later for whole-body autoradiography [1]. The study shows that the small molecule readily penetrates into the post-vascular space of all organs of the body, except for the brain and spinal cord. The limited penetration of drugs into the brain is the rule, not the exception. Essentially, 100% of large-molecule pharmaceutics, including peptides, recombinant proteins, monoclonal antibodies, RNA interference (RNAi)-based drugs and gene therapies, do not cross the BBB.

Just for amusement, here are the radioactivity levels observed in a mouse that had been injected with radiolabeled histamine:

Cross-section of a mouse administered radiolabeled histamine. Black indicates the presence of histamine. The brain and spinal cord lack any radiolabeled histamine because it is excluded by the BBB. (From Pardridge, 2007)

Considering that the putative peptides comprising Cerebrolysin are ~100 times larger than histamine, the assumption ought to be that none of the components of Cerebrolysin other than free amino acids enter the brain.

The two main criteria for a molecule to cross the BBB are size and hydrophobicity, as described in this box:

The neurotrophic peptides and peptide fragments that are supposedly in Cerebrolysin fail both criteria.

Being small and hydrophobic should be considered a near-necessary condition for a molecule to cross the BBB, but is still not at all sufficient. For the vendors of Cerebrolysin to simply assert that their product contains peptides that cross the BBB reveals either profound ignorance or a willingness to lie to their customers.

While there are endogenous mechanisms for blood-to-brain transport of proteins, this only occurs for specific proteins that have a dedicated transport mechanism. For example, insulin and IGF-1 have well-characterized BBB transport mechanisms. IGF-1 (and likely IGF-2) are the only neurotrophic factors with such mechanisms, and they are likely unique in this respect.

Concluding metascience thoughts

The burden of proof is on the proponents of Cerebrolysin to demonstrate that Cerebrolysin contains neurotrophic peptides and that they cross the blood-brain barrier.

What are we to make of the hundreds of publications that show effects from Cerebrolysin in rats and humans? Well, they are likely wrong.

The replication crisis and work of Ionnidis and other metascientists leads us to believe that most scientific research is false, especially in biomedicine, and especially in lower-tier biomedical journals, where all the primary source papers on Cerebrolysin appear.

The literature on Cerebrolysin, while very extensive and impressive-looking, is plagued with problems which are widespread in science:

- Conflicts of interest biasing research, and conflicts not being reported (one study suggests that around 15% of biomedical review articles do not properly report conflict of interests).

- Publication bias (we could find zero articles reporting 100% null results).

- Shoddy techniques (using diagnostic instruments that have not been rigorously validated, using jerry-rigged home-grown lab equipment).

- No pre-registration, improper study design, small sample sizes, p-hacking, the file drawer effect.

Clearly, we’ve got a lot of work to do to clean up science.

- ^

Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Czech Republic, Kazakhstan, Mexico, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Vietnam

- ^

The top 10 articles:

1. Heiss, et al (2012): “This study was funded by EVER Neuro Pharma GmbH, Oberburgau 3, Austria…. The authors received an honorarium related to this work from the sponsor and support for travel.”

2. Muresanu et al (2015): “Herbert Moessler, PhD: Department of Clinical Research, EVER Neuro Pharma GmbH, Unterach.”

3. Bae et al (2015): “This research was funded by the Keunhwa Pharm. Co. Ltd., Seoul, Korea, and Ebewe Pharmaceuticals Ltd.”

4. Novak et al (2011): “Supported by EBEWE Neuro Pharma GmbH”

5. Alvarez et al (2016): “Herbert Moessler is an employee of EBEWE Pharma, Research Department” … “The study has been funded by a grant from EBEWE Pharma”

6. Windisch et al (2011): “One of the authors, Moessler, is an employee of EBEWE Arzneimittel GmbH”.

7. Panisset et al (2002): “Herbert Moessler is an employee of EBEWE Pharma.”

8. Chen et al (2013): The only one with no apparent conflict of interest! Note: this is a different Chen et al (2013) citation than the Cochrane review mentioned elsewhere.

9. Poon 2020: “This study was funded by Ever Neuro Pharma GmbH.”

10. Alvarez 2011: “This study was sponsored by EBEWE Pharma.”

- ^

Using nitrogen content is an older method for measuring protein in a biological sample. It works well because virtually all the nitrogen in a biological sample is located in proteins.

- ^

Some might respond with examples of cleaved protein fragments that retain signaling properties (e.g. the C-peptide that is produced during insulin synthesis) or peptide analogs of endogenous proteins that are much smaller while producing the same signaling as the endogenous peptide. The first example is not a valid comparison because this kind of cleavage event is highly specific, producing the same cleavage each time. It is more common for a peptidase to irreversibly inactivate a protein by cleaving it just once. A protein breakdown that occurs postmortem, in a tissue lysate like blended pig brain, is nonspecific and unlikely to produce functional fragments.

- ^

We found a paper that measured the distribution of the lengths of peptide fragments for multiple proteins after common enzymatic degradation procedures. From Kisselev et al (1998)

The distribution of fragments was invariant across different proteins. The most common length of a peptide was ~1000 Da. Since the average size of an amino acid is 110 Da, this means the most common length of a peptide fragment was 9 amino acids. This suggests that you would need to do a very aggressive enzymatic digestion procedure --analogous to what occurs in your stomach --to yield a solution that is 75% amino acids. Anyway, Kisselev et al (1998) still supports our assertion that it would be impossible to produce a hydrolysate where 25% was ~10 kDa, and 75% ~110 Da (i.e. single amino acids).

- ^

In general, a drug being efficacious in treating neurological issues (e.g. stroke) does not imply that the same drug will benefit an otherwise healthy person. In fact, it may do harm. The Algernon principle applies — drugs are unlikely to increase intelligence since evolution would have likely discovered that already. Ever Pharma’s marketing makes it seem like Cerebrolysin will be helpful to anyone, and this claim is widely touted online.

Claude is fine if you ask him to cite his sources since you won’t be directly relying on Claude. It’s still prudent to check the sources.