Relatedly, I've found that if I don't keep representation and traversal cleanly in my model as separable layers they can get confabulated with one another and assumptions about the representation automagically get assigned to the traversal and vice versa.

Even more generally, training a little classifier that is sensitive to the energy signature of type errors has dissolved most philosophical confusions.

Even more generally, training a little classifier that is sensitive to the energy signature of type errors has dissolved most philosophical confusions.

Could you explain that? maybe even, like, attempt the explanation five times with really high human-brain "repetition penalty"? This sounds interesting but I expect to find it difficult to be sure I understood. I also expect a significant chance I already agree but don't know what you mean, maybe bid 20%.

The ideal version of this would be 'the little book of type errors', a training manual similar to Polya's How to Solve It but for philosophy instead of math. The example Adam opens the post with is a good example, outlining a seemingly reasonable chain of thoughts and then pointing out the type error. Though, yes, in an ideal world it would be five examples before pointing it out so that the person has the opportunity to pattern complete on their own first (much more powerful than just having it explained right away).

In the Sorites paradox, the problem specification confabulates between the different practical and conceptual uses of language to create an intuition mismatch, similar to the Ship of Theseus. A kind of essentialist confusion that something could 'really be' a heap. The trick here is to carefully go through the problem formulation at the sentence level and identify when a referent-reference relation has changed without comment. More generally, our day-to-day use of language elides the practical domain of the match between the word and expectation of future physical states of the world. 'That's my water bottle'->a genie has come along and subatomically separated the water bottle, combined it with another one and then reconsituted two water bottles that superficially resemble your old one, which one is yours? 'Yeah, um, my notion of ownership wasn't built to handle that kind of nonsense, you sure have pulled a clever trick, doesn't a being who can do that have better things to do with their time?'

Even more upstream, our drive towards this sort of error seems a spandrel of compression. It would be convenient to be able to say X is Y, or X=Y and therefore simplify our model by reducing the number of required entities by one. This is often successful and helpful for transfer learning, but we're also prone to handwave lossy compression as lossless.

Is it really a deontological spin? Seems like the rationale is that we value long-term calibration, coherence, and winning on meaningful and important problems, and we don’t want to sacrifice that for short-term calibration/coherence/winning on less meaningful or important problems. Still seems consequentialist to me.

To nitpick your example, staring with a simple model in order to get to a simple theory seems to be quite a decent approach. At least to get a grasp on the problem. Of course you want to keep that it mind - the usefulness of spherical cows is quite limited.

Would you say that perfect being the enemy of good enough intersects with this?

And it feels like becoming a winner means consistently winning.

Reminds me strongly of the difficulty of accepting commitment strategies in decision theories as in Parfit's Hitchhiker: one gets the impression that a rational agent win-oriented should win in all situations (being greedy); but in reality, this is not always what winning looks like (optimal policy rather than optimal actions).

For it conjures obstacles that were never there.

Let's try apply this to a more confused topic. Risky. Recently I've slighty updated away from the mesa paradigm, reading the following in Reward is not the optimization target:

Stop worrying about finding “outer objectives” which are safe to maximize.[9] I think that you’re not going to get an outer-objective-maximizer (i.e. an agent which maximizes the explicitly specified reward function).

- Instead, focus on building good cognition within the agent.

- In my ontology, there's only one question: How do we grow good cognition inside of the trained agent?

How does this relate to the goal/path confusion? Alignment paths strategies:

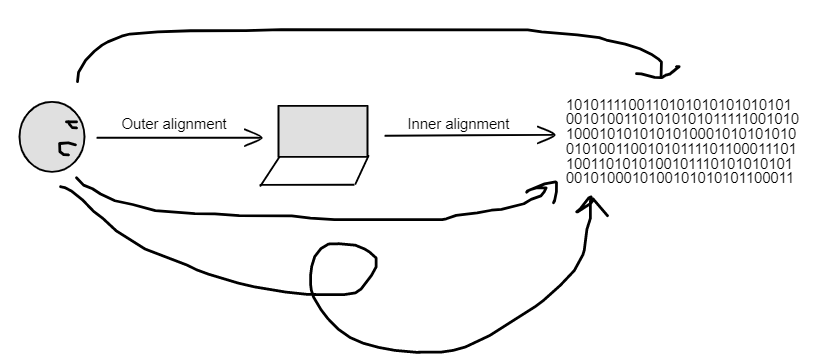

Outer + Inner alignment aims to be an alignment strategy, but only the straight path one. Any homotopic alignment path could be safe as well, our only real concern.

Say you are working on formulating a new scientific theory. You’re not there yet, but you broadly know what you want: a simple theory that powerfully compresses the core phenomenon, and suggests a myriad of new insights.

If you’re anything like me, at least part of you now pushes for focusing on simplicity from the get go. Let’s aim for the simplest description that comes easily, and iterate from that.

Did you catch the jump?

I started with a constraint on the goal — a simple theory — and automatically transmuted it into a constraint on the path — simple intermediary steps.

I confused “Finding a simple theory” with “Finding a simple theory simply”.

After first uncovering this in my own reasoning, I now see this pattern crop everywhere:

In the language of moral philosophy, this pattern amounts to adding a deontological spin on a consequentialist value. Even though it can prove valuable (in AI alignment for example), doing this unconsciously and automatically leads to problems after problems.

For it conjures obstacles that were never there.

This post is part of the work done at Conjecture.

Thanks to Clem for giving me the words to express this adequately.