One of the things that makes Michael Vassar an interesting person to be around is that he has an opinion about everything. If you locked him up in an empty room with grey walls, it would probably take the man about thirty seconds before he'd start analyzing the historical influence of the Enlightenment on the tradition of locking people up in empty rooms with grey walls.

Likewise, in the recent LW meetup, I noticed that I was naturally drawn to the people who most easily ended up talking about interesting things. I spent a while just listening to HughRistik's theories on the differences between men and women, for instance. There were a few occasions when I engaged in some small talk with new people, but not all of them took very long, as I failed to lead the conversation into territory where one of us would have plenty of opinions.

I have two major deficiencies in trying to mimic this behavior. One, I'm by nature more of a listener than speaker. I usually prefer to let other people talk so that I can just soak up the information being offered. Second, my native way of thought is closer to text than speech. At best, I can generate thoughts as fast as I can type. But in speech, I often have difficulty formulating my thoughts into coherent sentences fast enough and frequently hesitate.

Both of these problems are solvable by having a sufficiently well built-up storage of cached thoughts that I don't need to generate everything in real time. On the occasions when a conversations happens to drift into a topic I'm sufficiently familiar with, I'm often able to overcome the limitations and contribute meaningfully to the discussion. This implies two things. First, that I need to generate cached thoughts in more subjects than I currently have. Seconds, that I need an ability to more reliably steer conversation into subjects that I actually do have cached thoughts about.

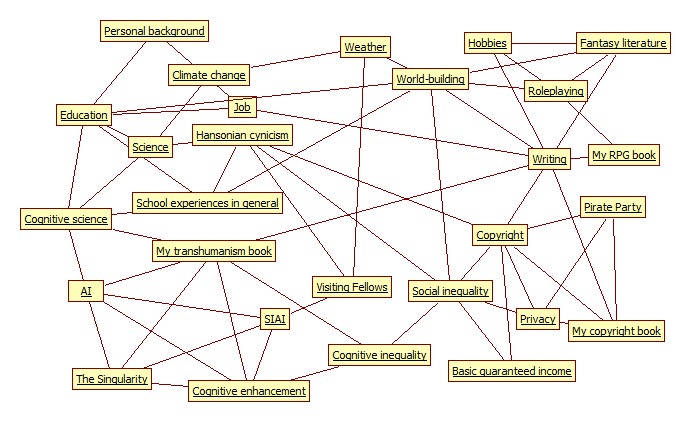

Below is a preliminary "conversational map" I generated as an exercise. The top three subjects - the weather, the other person's background (job and education), people's hobbies - are classical small talk subjects. Below them are a bunch of subjects that I feel like I can spend at least a while talking about, and possible paths leading from one subject to another. My goal in generating the map is to create a huge web of interesting subjects, so that I can use the small talk openings to bootstrap the conversation into basically anything I happen to be interested in.

This map is still pretty small, but it can be expanded to an arbitrary degree. (This is also one of the times when I wish my netbook had a bigger screen.) I thought that I didn't have very many things that I could easily talk with people about, but once I started explicitly brainstorming for them, I realized that there were a lot of those.

My intention is to spend a while generating conversational charts like this and then spend some time fleshing out the actual transitions between subjects. The benefit from this process should be two-fold. Practice in creating transitions between subjects will make it easier to generate such transitions in real time conversations. And if I can't actually come up with anything in real time, I can fall back to the cache of transitions and subjects that I've built up.

Naturally, the process needs to be guided by what the other person shows an interest in. If they show no interest in some subject I mention, it's time to move the topic to another cluster. Many of the subjects in this chart are also pretty inflammable: there are environments where pretty much everything in the politics cluster should probably be kept off-limits, for instance. Exercise your common sense when building and using your own conversational charts.

(Thanks to Justin Shovelain for mentioning that Michael Vassar seems to have a big huge conversational web that all his discussions take place in. That notion was one of the original sources for this idea.)

You can't create a procedure that maps out every branch in a conversation tree, no. But I think you are underestimating the ritualization and standardization of social activity. There really are patterns in how people do things. There are considerable norms, rules, and constraints. People who are intuitively social (whether they became that way earlier or later in life) may have trouble articulating these patterns.

Within these constraints, there are infinite ways to behave, and you can be as spontaneous as you want. Intuitively social people experience social interaction to be natural and spontaneous because their intuitions keep them within those constraints.

Conversation is "procedureless" in the same sense that musical improvisation is "procedureless." You can't map out the rules for improvisation in advance. But there are some chords that work well (or badly) after others that you can know in advance. You can know whether you are in a major or minor key, and if you have the concept of major/minor mode and key, then it will funnel your spontaneity in a direction that will create a harmonious result.

In contrast, a socially unskilled person is like someone improvising with concepts such as "mode" and "key." Their results are practically guaranteed to violate the constraints of what we consider to be good music. This of what happens when an untrained person plinks away at a piano.

While both conversation and musical improvisation are procedureless, there are procedures for learning those things. Musicians practice scales and etudes. Applying the same kind of process to learning social interaction is looked on as strange, because of the false expectation that people should be able to learn it naturally (even if the reason they haven't is because they were locked out of social interaction for years due to bullying and exclusion that was no fault of their own).

Actually, introversation is a component of temperament that does seem to have a biological basis.

I agree that for most people with low social skills probably aren't biologically determined to be quite so bad at socializing. Even though people have different levels of potential due to biology, most people probably don't come anywhere near meeting their potential. But the problem isn't really their will; it's their social development and the associations that they have developed with social interaction.

Someone's present-day social skills are due to an interaction of biological and environmental factors. Temperament on its own generally doesn't determine social skills; instead, their temperament influences social experiences, which determine what level of social skills are learned. In the case of people with low social skills and different temperaments (e.g. introversion), these people generally got that way because their temperament made them "get off on the wrong foot" with their peers socially, often resulting in bullying, exclusion, or abuse. In another peer environment, even an introverted individual could develop social skills just fine.

Actually, there are pretty large individual differences in susceptibility to anxiety. People with lower "anxiety threshold" (i.e. it takes less to make them anxious) really do have things harder. I managed to conquer anxiety at the level of social phobia, but to do I had to recognize certain challenges (and advantages) that my temperament gave me, and learned to cope with them.

This works for some people once they have certain prerequisites for learning from their attempts at socializing. The trick is to get them to those prerequisites.

Certainly there are patterns in social interaction.

However, I think that if you go into social interaction aware of these patterns and meaning to act on them, then this very awareness will in fact ruin your social interaction, because one of the rules of genuine social interaction is that it's free flowing and natural-feeling. If you treat it like a formula, you'll break it.