Frankly, I think the biggest cause of the "stagnation" you're seeing is unwillingness to burn resources as the world population climbs toward 8 billion. We could build the 1970s idea of a flying car right now; it just wouldn't be permitted to fly because (a) it would (noisily) waste so much fuel and (b) it turns out that most people really aren't up to being pilots, especially if you have as many little aircraft flying around from random point A to random point B as you have cars. A lot of those old SciFi ideas simply weren't practical to begin with.

... and I think that the other cause is that of course it's easier to pick low hanging fruit.

It may not be possible to build a space elevator with any material, ever, period, especially if it has to actually stay in service under real environmental conditions. You're not seeing radically new engine types because it's very likely that we've already explored all the broad types of engines that are physically possible. The laws of physics aren't under any obligation to support infinite expansion, or to let anybody realize every pipe dream.

In fact, the trick of getting rapid improvement seems to be finding a new direction in which to expand...

In 1970, you might not have included "information"... because wasn't so prominent in people's minds until a bunch of new stuff showed up to give it salience.

I disagree. Any self-respecting history of technology includes invention of writing and printing press. Those two are like among the most important technology ever invented. You'd have "information" category just to include writing and printing press.

Also the phonograph, telegraph, telephone, radio, and television! If “information” wasn't a category before the late 1800s, it was by then.

Manufacturing

- Production per hour labor has increased in the USA and elsewhere.

- I have 3D printer in my living room.

Transportation

Home delivery is way cheaper than it used to be. Mail order has been a thing for a long time, but good mail-order products are new. It's not impractical to buy everything you need without going to a store.

Manufacturing + Transportation

When you combine the developments of manufacturing plus transportation you get brand new phenomena, like being able to start a consumer hardware startup out of your living room. This doesn't affect everyone's living room, but my living room is full of shipping supplies and my basement has a small factory in it.

War

The B-2 stealth bomber reached initial operational capability in 1997. GPS and satellite mapping are ubiquitous. Guided missiles, real-time satellite surveillance and Predator drones are more capable today than in 1980s science fiction. Laser defenses, Gauss cannons and exoskeletons are on the way.

We also do nuclear tests with computer simulations instead of physical atom bombs. This particular example illustrates how physical technologies can turn into digital technologies. Physical technologies turning into digital technologies can create the illusion that physical technology is stagnating.

The fact that some advances exist is entirely consistent with the thesis that the overall rate of advance has slowed down, as the original article points out.

While I don't agree with everything, this is a top-quality comment deserving to be its own post, consider posting it as top-level?

(Epistemic status: lame pun)

I don't believe 1970 had significant deployment of ... EDM, or probably a bunch of other process I'm forgetting about

It was called “disco” in the 70s

Gordon, however, points out that GDP has never captured consumer surplus, and there has been plenty of surplus in the past. So if you want to argue that unmeasured surplus is the cause of an apparent (but not a real) decline in growth rates, then you have to argue that GDP has been systematically increasingly mismeasured over time.

So far, I’ve only heard one only argument that even hints in this direction: the shift from manufacturing to services. If services are more mismeasured than manufactured products, then in logic at least this could account for an illusory slowdown. But I’ve never seen this argument fully developed.

The argument which jumps to my mind is that value-of-bits is more systematically mismeasured than value-of-atoms. Information is generally cheap to copy. Marginal cost of copying the information is close to zero, therefore its price will be close to zero. That is exactly the condition under which GDP would be an especially poor measure, so we'd expect GDP to be increasingly poor as a larger percentage of growth shifts into information goods.

I still think the overall stagnation case you put forward is strong, though.

Something missing from the top-level post: why stagnation.

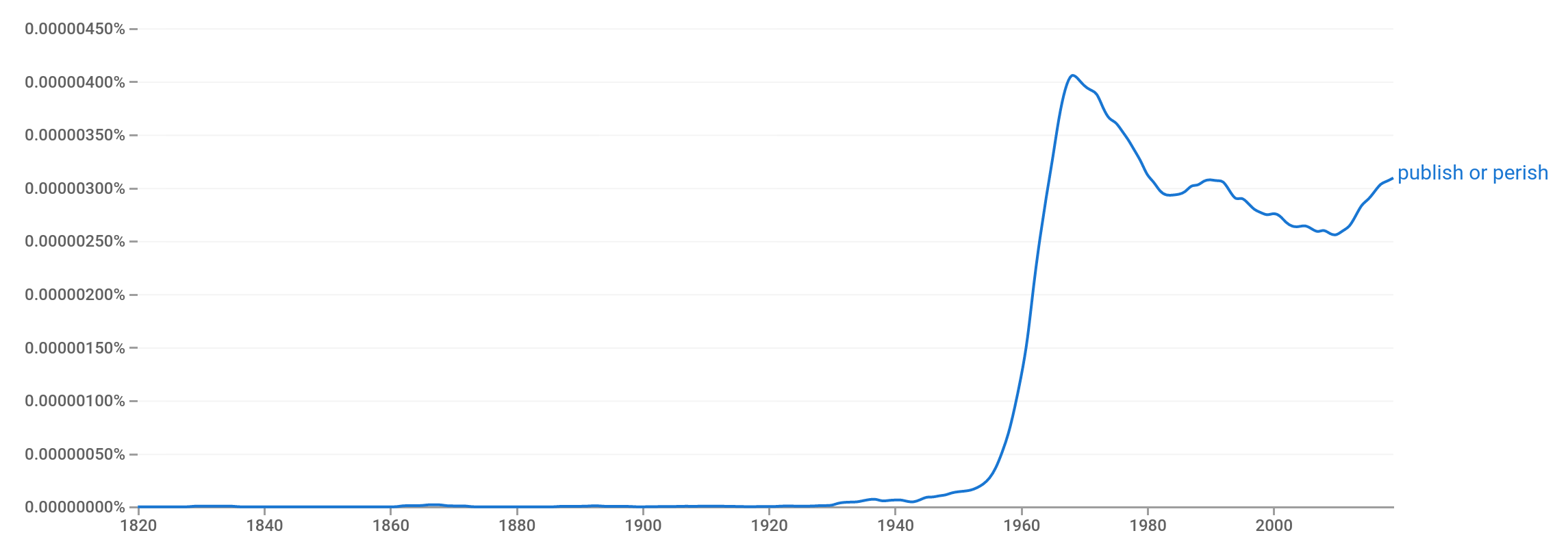

I'll just put out that one of the tiny things that most gave me a sense of "fuck" in relation to stagnation was reading an essay written in 1972 that was lamenting the "publish or perish" phenomenon. I had previously assumed that that term was way more recent, and that people were trying to fix it but it would just take a few years. To realize it was 50 years old was kinda crushing honestly.

Here's google ngrams showing how common the phrase "publish or perish" was in books through the last 200 years. It was coined in the 30s and took off in the 60s, peaking in 1968. Interesting & relevant timing!

I think there's a case for two different sources: one external, the simple lack of any further low hanging fruit to exploit, and one internal, which is exactly this - the increasing inadequacy of our institutions to create the conditions for innovation, often caused paradoxically by the excessive focus on promoting innovation. "If scientists gave us all this cool stuff by working on their own, imagine how good they will be if we hire a lot more of them and pit them into a competition for funding with each other!" was a catastrophically stupid idea, assuming humans can be made to produce highly creative work on command and like clockwork. It led to short-termism, creating a humongous confusing, amorphous mass of tiny innovations, many of which non replicable or straight up bogus, and efficiently killing off any incentive to actually work on long term, solid, sweeping discoveries.

While reviewing two other progress studies posts for the LW 2019 Review (Concrete and Artificial Fertilizer) I found myself thinking "these seem neat, but I don't feel like I can directly apply the knowledge here very much. What I really wish Jason Crawford would write (someday) are posts that take a birds eye view of progress, taking advantage of the gestalt of all the different object level "how did we invent X?" research and then deriving insights about the bigger picture.

So, I am quite delighted by this post, which I feel like does exactly that.

I think there is a partial explanation that comes from Goodhart's law and human desire for superstimulation, and the ease with which that type of superstimulation is now available.

Capitalism is effective at fulfilling human desires, which are measured on the level of personal tradeoffs, taken on a very short time scale. The measure is not about human progress write large, but until people's basic needs are satisfied, the two are very well correlated; enough food, labor saving devices, etc. If we are trying to advance "human progress" than at a certain point, the individual-level, short term motive no longer suffices.

If you want longevity, you need people to be willing to pay for it now - but they aren't. If you want space travel, you need the beneficiaries to exist now, not in a few generations. But this got worse, because we've found a much faster feedback loop for desires than physical progress - screens. They are dopamine devices, and they absorb almost unlimited capacity for desire. That means we're wireheading, and any longer term goals will be ignored.

I'd be really happy to hear ideas for how this can be routed around, as short of a global pandemic to convince people to actually care about some specific technological advance like a vaccine, I don't know what motivates society enough to overcome this.

Curated.

As noted in a previous comment: I appreciate this post because I think it's fairly hard to make sense of all the stuff going on in the technological-innovation-space, if you're just looking at individual "trees" rather than the collective "forest." I know Jason Crawford has been thinking a lot about this space over a long time, getting to look at a lot of individual trees enough to take stock of how the collective forest is doing.

So, getting to see how he changed his mind about things, and how that exploration fed into updates on the stagnation hypothesis, was useful to me.

I can't point to the episode(s) or post(s), but I believe both on his blog and on his podcast Conversations with Tyler, Tyler has expressed the idea that we may be currently coming out of the stagnation of stuff in the Real World driven by stuff like SpaceX, CRISPR, mRNA, etc.

...Since then, the “third Industrial Revolution”, starting in the mid-1900s, has mostly seen fundamental advances in a single area: electronic computing and communications. If you date it from 1970, there has really been nothing comparable in manufacturing, agriculture, energy, transportation, or medicine—again, not that these areas have seen zero progress, simply that they’ve seen less-than-revolutionary progress. Computers have completely transformed all of information processing and communications, while there have been no new types of materials, vehicles,

effective debate notes: I've read main points of every first-level comment in this thread and the author's clarification.

epistemic status: This argument is mostly about values. I hope we can all agree with the facts I mentioned here, but can also consider this alternative framework which I believe is a "better map of reality".

I disagree with your conclusion because I disagree with your model of classification of tech frontiers. In the body of this article and most comments, people seem to agree with your division of technology into 6 parts. Here's why I th...

When it comes to medicine I think the key thing we notice stagnation is in lifespans. Focusing on individual diseases is misleading. Curing cancer is commonly seen as being worth three years in life-span. Health in Hong-Kong is two times curing cancer better then health in the US if you use lifespan as your measuring stick.

Looking at the history it seems interesting that the change in progress in lifespan was more in the early 1960s then in the 1970s. The Kefauver Harris Amendment in 1962 might be one of the key drivers.

In the last decades we had con...

“Go into a room and subtract off all of the screens. How do you know you’re not in 1973, but for issues of design?”

At least if you’re in an average grocery store, you can tell it’s the 2000s from the greatly improved food selection

I speculate that there may be anthropic reasons for some of the stagnation.

In particular, I suspect the slowdown in growth of energy production may be what we would expect to see because in worlds where energy production grew faster we would have also had more abundant and more powerful weapons that would have been more likely to kill more humans, thus making it less likely to find oneself living in a world where such growth didn't decrease.

As for transportation, I would say the average time to get to a place have dropped considerably in past 50 years, not because of any specific invention, but because airplanes has become less toys for the rich and more of buses with wings available to everyone. Similarly, densification of the motorway system made it faster to go places by car.

It's not clear, of course, whether that kind of thing counts as technological progress. But if not so, what kind of progress is it?

There was far more progress in aviation from 1920–1970 than from 1970–2020. In 1920, planes were still mostly made of wood and fabric. By 1970 most planes had jet engines and flew at ~600mph. Today planes actually fly a bit slower than they did in 1970. Yes, there has been progress in safety and cost, but it doesn't compare to the previous 50-year period.

Similar pattern for automobiles and even highways.

I mostly agree with your thesis, but I noticed that you didn't mention agriculture in the last section, so I looked up some numbers.

The easiest stat I can find to track long-term is the hours of labor required to produce 100 bushels of wheat [1].

1830: 250 - 300 hours

1890: 40 - 50 hours

1930: 15 - 20 hours

1955: 6 - 12 hours

1965: 5 hours

1975: 3.75 hours

1987: 3 hours

That source stops in the 1980s, but I found another source that says the equivalent number today is 2 hours [2]. That roughly matches the more recent data on total agricultural productivity f...

Edit to shorten (more focus on arguments, less rhetorics), and include the top comment by jbash as a response / second part. The topic is important, but the article seems to have a bottom line already written.

I wonder about the question of catch-up growth.

There's a point raised in Is Scientific Progress Slowing Down by Tyler Cowen and Ben Southwood about problems relating to using TFP as an estimate of the value of progress, which is that it is hard to categorize ideas which are adopted late. Duplicating one of the quotes in the comments there:

...To consider a simple example, imagine that an American company is inefficient, and then a management consultant comes along and teaches that company better personnel management practices, thereby boosting productivity. Do

Note that this can be modeled pretty simply.

Evolution is slow and for the sake of argument, assume human intelligence has not changed over the time period you have mapped. If humans haven't gotten any smarter, and the next incremental step in the technology areas you have mentioned requires increasingly sophisticated solutions and thought, then you would expect progress to slow. Fairly obvious case of diminishing returns.

Second, computers do act to augment human intelligence, and more educated humans alive increase the available brainpower, but...

Another argument in favor of the slow down is that you don't hear people arguing that innovation is speeding up. It's either slowing down or the same as before.

I’m not sure you are talking about technology advancement but rather the gifts of different hydrocarbon ages. Your IR1 to me is better described as everything we could do with coal. IR2 is everything we could do with oil. IR3 seems different to me, if humanity invented true AI -will we be literally gods?

Also there is the issue of order of magnitude improvements only being noticeable when they pass the human scale and seeming irrelevant either side. Commuting to work in a flying car might be fun, but flying my desk home at the speed of light is far faster a...

Great article, small (but maybe significant) nitpick. I don't think there's great evidence that innovation-by-bureaucracy is bad, and I actually think it's pretty good. The sheer quantity of innovation produced by the two world wars and space program is spectacular, as is the record of DARPA post WW2. Even the Soviet Union could do could innovation by bureaucracy. At the company level, it's true that lots of big innovations come from small new companies, but at the same time Bell Labs, Intel, Sony were monsters. I actually think that the retreat of government is a big part of problem.

Maybe it's wishful thinking but I think the stagnation is temporary. I think there is reason to believe that progress can come in waves. Scientific advancements of the early 1900s led to much of the technological advancements of pre and post war era. So to, I think it reasonable that computation advancements of the last 30 or so years will lead to a number of interesting advancements:

I think it is reasonable to assume that many of the items from the list below will happen in the next 10 to 20 years.

- Self driving cars

- 2.5x batteries

- electric cars

- el

Maybe it's because we're now using the fiat system. The fiat system was introduced in 1971, and everything has been going downhill from there. It could be correlation or causation. But it's definitely something. This makes it more vivid:

https://wtfhappenedin1971.com/

And what’s the matter with bits, anyway? Are they less important than atoms?

Arguably, yes, because they are less fundamental. A revolution in our understanding of the fundamental laws of physics begets more secondary revolutions down the line; quantum mechanics alone gave us lasers, nuclear power and those very bits - to name but a few. So from a revolution in our understanding of the world comes the promise of more revolutions once that reaches the application stage. Understanding quantum gravity might lead to warp drives. But no matter how great ou...

Seems to me that solving the problem of the safe mass-production, storage and transport of gaseous and liquid hydrogen would be the game-changer, for terrestrial needs as well as space travel. It can be gotten from water or even air. If the danger of handling could be reduced, it would surpass petrol as the primary fuel and then off we go. Solves the carbon problem and the energy resource problem.

Then if someone figured out how to better harness the sun's energy... Of the energy that reaches earth, what do we capture and put to use now, like .001%? Or hydroelectricity from the tides? Lot more reliable than winds. All the current problems/roadblocks seems to be energy-related.

There is one aspect which you almost completely ignore in your post and which I believe is vital: WHY is stagnation bad? WHY is progress good? You make it sound as though you just want fancy gadgets for the sake of having fancy gadgets.

You have a "quantitative" section, but what exactly are you trying to quantify? Why is economic growth good?

You should spend more time pondering: What (quantifiable) factors are valuable in and of themselves? And have these factors improved or stagnated?

For example, I believe there is less famine and fewer people living in e...

“We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters,” says Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund, expressing a sort of jaded disappointment with technological progress. (The fact that the 140 characters have become 280, a 100% increase, does not seem to have impressed him.)

Thiel, along with economists such as Tyler Cowen (The Great Stagnation) and Robert Gordon (The Rise and Fall of American Growth), promotes a “stagnation hypothesis”: that there has been a significant slowdown in scientific, technological, and economic progress in recent decades—say, for a round number, since about 1970, or the last ~50 years.

When I first heard the stagnation hypothesis, I was skeptical. The arguments weren’t convincing to me. But as I studied the history of progress (and looked at the numbers), I slowly came around, and now I’m fairly convinced. So convinced, in fact, that I now seem to be more pessimistic about ending stagnation than some of its original proponents.

In this essay I’ll try to capture both why I was originally skeptical, and also why I changed my mind. If you have heard some of the same arguments that I did, and are skeptical for the same reasons, maybe my framing of the issue will help.

Stagnation is relative

To get one misconception out of the way first: “stagnation” does not mean zero progress. No one is claiming that. There wasn’t zero progress even before the Industrial Revolution (or the civilizations of Europe and Asia would have looked no different in 1700 than they did in the days of nomadic hunter-gatherers, tens of thousands of years ago).

Stagnation just means slower progress. And not even slower than that pre-industrial era, but slower than, roughly, the late 1800s to mid-1900s, when growth rates are said to have peaked.

Because of this, we can’t resolve the issue by pointing to isolated advances. The microwave, the air conditioner, the electronic pacemaker, a new cancer drug—these are great, but they don’t disprove stagnation.

Stagnation is relative, and so to evaluate the hypothesis we must find some way to compare magnitudes. This is difficult.

Only 140 characters?

“We wanted flying cars, instead we got a supercomputer in everyone’s pocket and a global communications network to connect everyone on the planet to each other and to the whole of the world’s knowledge, art, philosophy and culture.” When you put it that way, it doesn’t sound so bad.

Indeed, the digital revolution has been absolutely amazing. It’s up there with electricity, the internal combustion engine, or mass manufacturing: one of the great, fundamental, transformative technologies of the industrial age. (Although admittedly it’s hard to see the effect of computers in the productivity statistics, and I don’t know why.)

But we don’t need to downplay the magnitude of the digital revolution to see stagnation; conversely, proving its importance will not defeat the stagnation hypothesis. Again, stagnation is relative, and we must find some way to compare the current period to those that came before.

Argumentum ad living room

Eric Weinstein proposes a test: “Go into a room and subtract off all of the screens. How do you know you’re not in 1973, but for issues of design?”

This too I found unconvincing. It felt like a weak thought experiment that relied too much on intuition, revealing one’s own priors more than anything else. And why should we necessarily expect progress to be visible directly from the home or office? Maybe it is happening in specialized environments that the layman wouldn’t have much intuition about: in the factory, the power plant, the agricultural field, the hospital, the oil rig, the cargo ship, the research lab.

No progress except for all the progress

There’s also that sleight of hand: “subtract the screens”. A starker form of this argument is: “except for computers and the Internet, our economy has been relatively stagnant.” Well, sure: if you carve out all the progress, what remains is stagnation.

Would we even expect progress to be evenly distributed across all domains? Any one technology follows an S-curve: a slow start, followed by rapid expansion, then a leveling off in maturity. It’s not a sign of stagnation that after the world became electrified, electrical power technology wasn’t a high-growth area like it had been in the early 1900s. That’s not how progress works. Instead, we are constantly turning our attention to new frontiers. If that’s the case, you can’t carve out the frontiers and then say, “well, except for the frontiers, we’re stagnating”.

Bit bigotry?

In an interview with Cowen, Thiel says stagnation is “in the world of atoms, not bits”:

But again, why should we expect it to be different? Maybe bits are just the current frontier. And what’s the matter with bits, anyway? Are they less important than atoms? Progress in any field is still progress.

The quantitative case

So, we need more than isolated anecdotes, or appeals to intuition. A more rigorous case for stagnation can be made quantitatively. A paper by Cowen and Ben Southwood quotes Gordon: “U.S. economic growth slowed by more than half from 3.2 percent per year during 1970-2006 to only 1.4 percent during 2006-2016.” Or look at this chart from the same paper:

Gordon’s own book points out that growth in output per hour has slowed from an average annual rate of 2.82% in the period 1920-1970, to 1.62% in 1970-2014. He also analyzes TFP (total factor productivity, a residual calculated by subtracting out increases in capital and labor from GDP growth; what remains is assumed to represent productivity growth from technology). Annual TFP growth was 1.89% from 1920-1970, but less than 1% in every decade since. (More detail in my review of Gordon’s book.)

Analyzing growth quantitatively is hard, and these conclusions are disputed. GDP is problematic (and these authors acknowledge this). In particular, it does not capture consumer surplus: since you don’t pay for articles on Wikipedia, searches on Google, or entertainment on YouTube, a shift to these services away from paid ones actually shrinks GDP, but it represents progress and consumer benefit.

Gordon, however, points out that GDP has never captured consumer surplus, and there has been plenty of surplus in the past. So if you want to argue that unmeasured surplus is the cause of an apparent (but not a real) decline in growth rates, then you have to argue that GDP has been systematically increasingly mismeasured over time.

So far, I’ve only heard one only argument that even hints in this direction: the shift from manufacturing to services. If services are more mismeasured than manufactured products, then in logic at least this could account for an illusory slowdown. But I’ve never seen this argument fully developed.

In any case, the quantitative argument is not what convinced me of the stagnation hypothesis nearly as much as the qualitative one.

Sustaining multiple fronts

I remember the first time I thought there might really be something to the stagnation hypothesis: it was when I started mapping out a timeline of major inventions in each main area of industry.

At a high level, I think of technology/industry in six major categories:

Almost every significant advance or technology can be classified in one of these buckets (with a few exceptions, such as finance and perhaps retail).

The first phase of the industrial era, sometimes called “the first Industrial Revolution”, from the 1700s through the mid-1800s, consisted mainly of two fundamental advances: mechanization, and the steam engine. The factory system evolved in part out of the former, and the locomotive was based on the latter. Together, these revolutionized manufacturing, energy, and transportation, and began to transform agriculture as well.

The “second Industrial Revolution”, from the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s, is characterized by a greater influence of science: mainly chemistry, electromagnetism, and microbiology. Applied chemistry gave us better materials, from Bessemer steel to plastic, and synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. It also gave us processes to refine petroleum, enabling the oil boom; this led to the internal combustion engine, and the vehicles based on it—cars, planes, and oil-burning ships—that still dominate transportation today. Physics gave us the electrical industry, including generators, motors, and the light bulb; and electronic communications, from the telegraph and telephone through radio and television. And biology gave us the germ theory, which dramatically reduced infectious disease mortality rates through improvements in sanitation, new vaccines, and towards the end of this period, antibiotics. So every single one of the six major categories was completely transformed.

Since then, the “third Industrial Revolution”, starting in the mid-1900s, has mostly seen fundamental advances in a single area: electronic computing and communications. If you date it from 1970, there has really been nothing comparable in manufacturing, agriculture, energy, transportation, or medicine—again, not that these areas have seen zero progress, simply that they’ve seen less-than-revolutionary progress. Computers have completely transformed all of information processing and communications, while there have been no new types of materials, vehicles, fuels, engines, etc. The closest candidates I can see are containerization in shipping, which revolutionized cargo but did nothing for passenger travel; and genetic engineering, which has given us a few big wins but hasn’t reached nearly its full potential yet.

The digital revolution has had echoes, derivative effects, in the other areas, of course: computers now help to control machines in all of those areas, and to plan and optimize processes. But those secondary effects existed in previous eras, too, along with primary effects. In the third Industrial Revolution we only have primary effects in one area.

So, making a very rough count of revolutionary technologies, there were:

It’s not that bits don’t matter, or that the computer revolution isn’t transformative. It’s that in previous eras we saw breakthroughs across the board. It’s that we went from five simultaneous technology revolutions to one.

The missing revolutions

The picture becomes starker when we look at the technologies that were promised, but never arrived or haven’t come to fruition yet; or those that were launched, but aborted or stunted. If manufacturing, agriculture, etc. weren’t transformed, then how could they have been?

Energy: The most obvious stunted technology is nuclear power. In the 1950s, everyone expected a nuclear future. Today, nuclear supplies less than 20% of US electricity and only about 8% of its total energy (and about half those figures in the world at large). Arguably, we should have had nuclear homes, cars and batteries by now.

Transportation: In 1969, Apollo 11 landed on the Moon and Concorde took its first supersonic test flight. But they were not followed by a thriving space transportation industry or broadly available supersonic passenger travel. The last Apollo mission flew in 1972, a mere three years later. Concorde was only ever available as a luxury for the elite, was never highly profitable, and was shut down in 2003, after less than thirty years in service. Meanwhile, passenger travel speeds are unchanged over 50 years (actually slightly reduced). And of course, flying cars are still the stuff of science fiction. Self-driving cars may be just around the corner, but haven’t arrived yet.

Medicine: Cancer and heart disease are still the top causes of death. Solving even one of these, the way we have mostly solved infectious disease and vitamin deficiencies, would have counted as a major breakthrough. Genetic engineering, again, has shown a few excellent early results, but hasn’t yet transformed medicine.

Manufacturing: In materials, carbon nanotubes and other nanomaterials are still mostly a research project, and we still have no material to build a space elevator or a space pier. As for processes, atomically precise manufacturing is even more science-fiction than flying cars.

If we had gotten even a few of the above, the last 50 years would seem a lot less stagnant.

One to zero

This year, the computer turns 75 years old, and the microprocessor turns 50. Digital technology is due to level off in its maturity phase.

So what comes next? The only thing worse than going from five simultaneous technological revolutions to one, is going from one to zero.

I am hopeful for genetic engineering. The ability to fully understand and control biology obviously has enormous potential. With it, we could cure disease, extend human lifespan, and augment strength and intelligence. We’ve made a good start with recombinant DNA technology, which gave us synthetic biologics such as insulin, and CRISPR is a major advance on top of that. The rapid success of two different mRNA-based covid vaccines is also a breakthrough, and a sign that a real genetic revolution might be just around the corner.

But genetic engineering is also subject to many of the forces of stagnation: research funding via a centralized bureaucracy, a hyper-cautious regulatory environment, and a cultural perception of something scary and dangerous. So it is not guaranteed to arrive. Without the right support and protection, we might be looking back on biotech from the year 2070 the way we look back on nuclear energy now, wondering why we never got a genetic cure for cancer and why life expectancy has plateaued.

Aiming higher

None of this is to downplay the importance or impact of any specific innovation, nor to discourage any inventor, present or future. Quite the opposite! It is to encourage us to set our sights still higher.

Now that I understand what was possible around the turn of the last century, I can’t settle for anything less. We need breadth in progress, as well as depth. We need revolutions on all fronts at once: not only biotech but manufacturing, energy and transportation as well. We need progress in bits, atoms, cells, and joules.