(Cross-posted from my website. Podcast version here, or search "Joe Carlsmith Audio" on your podcast app.)

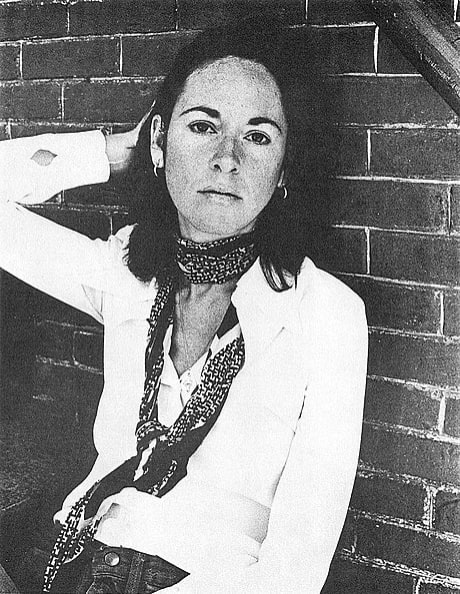

Louise Glück, one of my favorite poets, died yesterday.

I took a writing workshop with her back in 2009. I remember the force and precision of her words as she spoke, slowly, in class. There was a feeling like stones falling, one by one, into place. Like something large was being built, steadily, in simple movements, and you could see it forming.

I remember, too, a meeting in her office. It was early in the semester, and she hadn’t liked my poem. She wanted me to write from some place closer to where dreams come from – something deeper and more inchoate, some raw edge. She wanted what she had called, in my memory, a “real poem.”

I read various of her poems in that class, but the book of hers that has most stayed with me, and mattered most to me, came out later, in 2014: “Faithful and Virtuous Night.” I associate this book, in particular, with the dream-like quality of many of the poems — the way they shift underneath you as you read, full of quiet mystery and surprise. Here’s one of my favorites:

A Foreshortened Journey

I found the stairs somewhat more difficult than I had expected and so I sat down, so to speak, in the middle of the journey. Because there was a large window opposite the railing, I was able to entertain myself with the little dramas and comedies of the street outside, though no one I knew passed by, no one, certainly, who could have assisted me. Nor were the stairs themselves in use, as far as I could see. You must get up, my lad, I told myself. Since this seemed suddenly impossible, I did the next best thing: I prepared to sleep, my head and arm on the stair above, my body crouched below. Sometime after this, a little girl appeared on the top of the staircase, holding the hand of an elderly woman. Grandmother, cried the little girl, there is a dead man on the staircase! We must let him sleep, said the grandmother. We must walk quietly by. He is at that point in life at which neither returning to the beginning nor advancing to the end seem bearable; therefore, he has decided to stop, here, in the midst of things, though this makes him an obstacle to others, such as ourselves. But we must not give up hope; in my own life, she continued, there was such a time, though that was long ago. And here, she let her granddaughter walk in front of her so they could pass me without disturbing me.

I would have liked to hear the whole of her story, since she seemed, as she passed by, a vigorous woman, ready to take pleasure in life, and at the same time forthright, without illusions. But soon their voices faded into whispers, or they were far away. Will we see him when we return, the child murmured. He will be long gone by then, said her grandmother, he will have finished climbing up or down, as the case may be. Then I will say goodbye now, said the little girl. And she knelt below me, chanting a prayer I recognized as the Hebrew prayer for the dead. Sir, she whispered, my grandmother tells me you are not dead, but I thought perhaps this would soothe you in your terrors, and I will not be here to sing it at the right time.

When you hear this again, she said, perhaps the words will be less intimidating, if you remember how you first heard them, in the voice of a little girl.

Why do I love this poem? I wish I could say more directly. It feels like its touching, in me, that raw edge. Something about the journey, the unexplained staircase, preparing to sleep, the grandmother’s understanding. “In my own life, she continued, there was such a time.” And the little girl’s simple depth. “Then I will say goodbye now.”

The little girl, especially, has stayed with me, as have a few other similarly dream-like figures – the conductor in “Aboriginal Landscape,” the old woman in “A Sharply Worded Silence,” the concierge in “The Denial of Death.” The backdrop of these poems is often ethereal and unstable. It seems one way, then smoothly un-seems. “Right now you are a child holding hands with a fortune-teller,” Glück writes in “Theory of Memory.” “All the rest is hypothesis and dream.”

See, in “Aboriginal Landscape,” the way the speaker’s relationship to the cemetery evolves.

The cemetery was silent. Wind blew through the trees;

I could hear, very faintly, sounds of weeping several rows away,

and beyond that, a dog wailing.

At length these sounds abated. It crossed my mind

I had no memory of being driven here,

to what now seemed a cemetery, though it could have been

a cemetery in my mind only; perhaps it was a park, or if not a park,

a garden or bower, perfumed, I now realized, with the scent of roses —

douceur de vivre filling the air, the sweetness of living,

as the saying goes. At some point,

it occurred to me I was alone.

Where had the others gone,

my cousins and sister, Caitlin and Abigail?

By now the light was fading. Where was the car

waiting to take us home?

And yet the figures the speaker encounters have some kind of elusive understanding, like the grandmother’s on the staircase. Here, for example, is the conductor:

Finally, in the distance, I made out a small train,

stopped, it seemed, behind some foliage, the conductor

lingering against a doorframe, smoking a cigarette.

Do not forget me, I cried, running now

over many plots, many mothers and fathers —

Do not forget me, I cried, when at last I reached him.

Madam, he said, pointing to the tracks,

surely you realize this is the end, the tracks do not go further.

His words were harsh, and yet his eyes were kind;

this encouraged me to press my case harder.

But they go back, I said, and I remarked

their sturdiness, as though they had many such returns ahead of them.

You know, he said, our work is difficult: we confront

much sorrow and disappointment.

He gazed at me with increasing frankness.

I was like you once, he added, in love with turbulence.

Now I spoke as to an old friend:

What of you, I said, since he was free to leave,

have you no wish to go home,

to see the city again?

This is my home, he said.

The city — the city is where I disappear.

And here’s the old woman in “A Sharply Worded Silence”:

When I was young, she said, I liked walking the garden path at twilight

and if the path was long enough I would see the moon rise.

That was for me the great pleasure: not sex, not food, not worldly amusement.

I preferred the moon’s rising, and sometimes I would hear,

at the same moment, the sublime notes of the final ensemble

of The Marriage of Figaro. Where did the music come from?

I never knew.

Because it is the nature of garden paths

to be circular, each night, after my wanderings,

I would find myself at my front door, staring at it,

barely able to make out, in darkness, the glittering knob.

It was, she said, a great discovery, albeit my real life.

“My real life.” How do you discover your real life? How do you write a real poem? Part of it, for Glück, is gazing, and speaking, with frankness. Forthright, and without illusions.

People call her poetry “austere” and “terse.” She has, one senses, no time for bullshit. From “October”:

It is true there is not enough beauty in the world.

It is also true that I am not competent to restore it.

Neither is there candor, and here I may be of some use.

But what she strips away in pursuit of candor leaves something luminous. She is direct, but not dry. Indeed, in her hands, simple words take on strange power. “I want you.” “You are all that is wrong with my life and I need you and I claim you.” “It’s not the earth I’ll miss, it’s you I’ll miss.”

Here’s another of my favorites:

The Wild Iris

At the end of my suffering

there was a door.

Hear me out: that which you call death

I remember.

Overhead, noises, branches of the pine shifting.

Then nothing. The weak sun

flickered over the dry surface.

It is terrible to survive

as consciousness

buried in the dark earth.

Then it was over: that which you fear, being

a soul and unable

to speak, ending abruptly, the stiff earth

bending a little. And what I took to be

birds darting in low shrubs.

You who do not remember

passage from the other world

I tell you I could speak again: whatever

returns from oblivion returns

to find a voice:

from the center of my life came

a great fountain, deep blue

shadows on azure seawater.

I’ve returned, especially, to that line in the last stanza: “from the center of my life came a great fountain.” And to that seawater. Is that the great discovery? The poem speaks of a door at the end of suffering. Was there, somewhere, a glittering knob?

The other Glück poem that has really stayed with me is this one, from a series where she sometimes speaks to God from her garden.

Vespers

In your extended absence, you permit me

use of earth, anticipating

some return on investment. I must report

failure in my assignment, principally

regarding the tomato plants.

I think I should not be encouraged to grow

tomatoes. Or, if I am, you should withhold

the heavy rains, the cold nights that come

so often here, while other regions get

twelve weeks of summer. All this

belongs to you: on the other hand,

I planted the seeds, I watched the first shoots

like wings tearing the soil, and it was my heart

broken by the blight, the black spot so quickly

multiplying in the rows. I doubt

you have a heart, in our understanding of

that term. You who do not discriminate

between the dead and the living, who are, in consequence,

immune to foreshadowing, you may not know

how much terror we bear, the spotted leaf,

the red leaves of the maple falling

even in August, in early darkness: I am responsible

for these vines.

It feels like there’s a building pain in this poem: the heavy rains, the cold night, and then that breaking blight, and the black spots spreading. And then that last line, that taking-it-on. “I am responsible for these vines.” She loves the earth, and it causes her such pain. See, also, her 2004 “October”:

Is it winter again, is it cold again,

didn’t Frank just slip on the ice,

didn’t he heal, weren’t the spring seeds planted…

didn’t we plant the seeds,

weren’t we necessary to the earth,

the vines, were they harvested?

And see, too, her warnings in “The Sensual World”:

I caution you as I was never cautioned:

you will never let go, you will never be satiated.

You will be damaged and scarred, you will continue to hunger.

Your body will age, you will continue to need.

You will want the earth, then more of the earth–

Sublime, indifferent, it is present, it will not respond.

It is encompassing, it will not minister.

Meaning, it will feed you, it will ravish you,

it will not keep you alive.

She knew well that she was going to die. “My body,” she writes in “Crossroads,” “now that we will not be traveling together much longer, I begin to feel a new tenderness toward you, very raw and unfamiliar, like what I remember of love when I was young…” And loss is everywhere in her poetry: See, e.g., in “Primavera”: “Alas, very soon everything will disappear: the birdcalls, the delicate blossoms. In the end, even the earth itself will follow the artist’s name into oblivion.”

The artist, in that poem, leaves no signature – just a drawing of the sun in the dirt, and a “mood of celebration.” And in her acceptance speech for the Nobel prize, recorded less than six months before her death from cancer, Glück seems attracted to a type of anonymity – or at least, to the intimacy of encountering her readers in private, rather than in the public sphere. (Perhaps: in a fortune-teller’s tent, holding hands, with all the rest as mere hypothesis.) She quotes Dickinson as an example of this intimacy: “I’m Nobody! Who are you? Are you – Nobody – too? Then there’s a pair of us! Don’t tell!” Glück admits to wanting readers. But she wants to reach them “singly, one by one.” “You hear this voice?” she writes in “October.” “This is my mind’s voice.”

Specifically, though, she wanted her readers to participate, somehow, in her poetry. When Eliot says “let us go then, you and I,” Glück thinks he is asking something of the reader. She is, too.

Asking what? Well: many things, presumably. And the individual poems are the best place to look. In general, though, I think she asks for candor – and more, for some sort of intensity and directness of spirit. Perhaps it is a stretch to say that Glück’s is “spiritual” poetry. But she appears, on the page, as fiercely alive and attuned, in a world simultaneously dreamlike and raw, mythical and mundane.

How do you honor someone who has lived the way Glück, in her poetry, appears to live? By meeting them where they seek to stand. By searching out the same real life they sought – that greatest discovery. Here’s to the fountain she found.