[Edit: probably not as bad as it first looks. See comment for more thoughts.]

Long-term melatonin usage for insomniacs was associated with doubling of all-cause mortality*

New article from the American Heart Association seems pretty damning for long-term melatonin usage safety:

In a large, multinational real-world cohort rigorously matched on >40 baseline variables, long-term melatonin supplementation in insomnia was associated with an 89% higher hazard of incident heart failure, a three-fold increase in HF-related hospitalizations, and a doubling of all-cause mortality over 5 years.

*Caveats:

- we just have the abstract, not the full article

- observational study, not experimental

- their sample is only of insomniacs, not of the general population

Responses to the caveats:

- we'll get the full article soon-ish (probably a month or so?)

- it seems they did quite a bit of controlling? though we won't know how good their controlling was until the full article comes out

- I can't imagine that the validity of their results for non-insomniacs is many orders of magnitude less than for insomniacs — like, maybe a factor of two or five, but that'd still be a huge effect size

All things considered — this seems like a crazily high effect size. Am I missing something?

(Warning: relatively hot take and also not medical advice.)

Firstly, there's a major underlying confounder effect here which is the untracked severity of insomnia and it's correlation with the prescription of melatonin. If these are majorly coupled it could amount to most of the effect?

Secondly, here's a model and a tip for melatonin use as most US over the top pills I've seen are around 10mg which is way too much. I'll start with the basic mental model for why and then say the underlying thing we see.

TL;DR:

If you want to be on the safe side don't take more than 3mg of it per night. (You're probably gonna be fine anyway due to the confounder effects of long-term insomnia having higher correlation with long-term melatonin use but who knows how that trend actually looks like.)

Model:

There's a model for sleep which I quite like from Uri Alon (I think it's from him at least) and it is mainly as the circadian rhythm and sleep mechanism as a base layer signal for your other bodily systems to sync to.

The reasoning goes a bit like: Which is the most stable cycle that we could stabilise to? Well we have a day rhythm that is coupled to 24 hours a day each day, very stable compared to most other signals. That's the circadian rhythm which is maintained by your system's sleep.

What sleep does is that it is a reset period for the biological version of this as it sends out a bunch of low-range stable signals that are saying "hey gather around let's coordinate, the time is approximately night time." These brain signals don't happen in non-sleep and so they are easy to check.

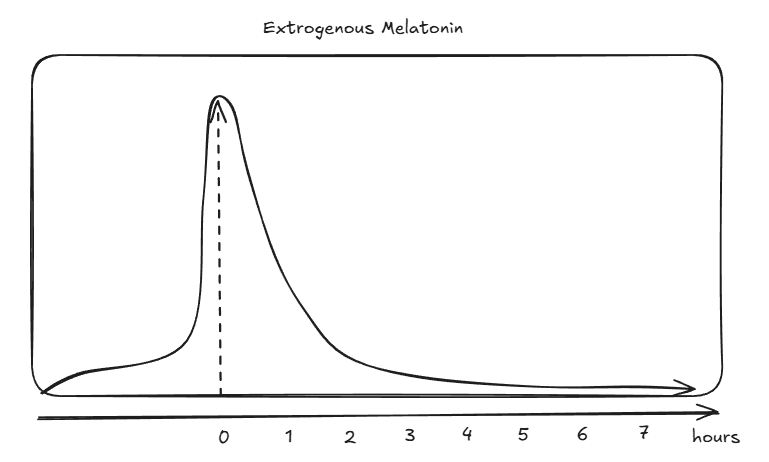

Melatonin is one of the main molecules for regulating this pattern and you actually don't need more than 0.3 mg (remember bioavaliability here) to double your existing amount that you already have in the body. Most over the counter medicine is around 10mg which is way too much. Imagine that you change one of the baseline signals of your base regulatory system and just bloop it the fuck out of the stratosphere for a concentrated period once everyday. The half life of melatonin is also something like 25-50 minutes so it decays pretty quickly as well which means that the curve ends up looking like the following:

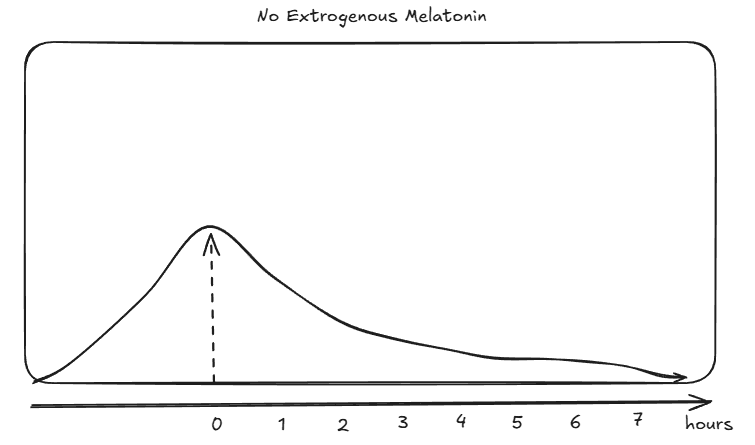

If you don't do this then your more natural curve looks something more like this:

Section 3 of the following talk about a desentisation of the MT2 part of melatonin as something that happens quite quickly: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/melatonin-receptor

So if you stratosphere your melatonin with 10 mg then your REM sleep will be fine but the sensitivity to your MT2 receptor will be a bit fucked which means worse deep sleep (which is important for your cardiovascular system!). Hence you will fall asleep but with worse deep sleep (Haven't checked if this is true but this could probably be checked pretty easily experimentally).

The bioavaliability of melatonin varies between 10 and 30% so if you aim for approximately your own intragenous generation of melatonin you should take 10 to 3x the amount existent in the system. For my own optimal sleep that is 0.5 mg of melatonin but that's because my own system already works pretty well and I just need a smaller nudge. The area under the curve part of the model is also a good reason to take slow release melatonin as it better approximates your normal melatonin curve.

(I need to get back to work lol but hopefully this helps a bit)

some updates:

(1) just spoke with a doctor[1] who'd looked into it a bit. he basically wasn't worried about it at all — his take was (paraphrasing quite a bit):

- causes of heart failure are numerous & complex — it'd be really confusing mechanistically if melatonin affected a sufficiently large subset of those causes sufficiently strongly to have this strong of an effect.

- also, because they're so numerous & complex, it seems pretty implausible that they could've done even close to a sane job of manually controlling for all of the right variables.

- [this bullet added by saul, not explicitly said by the doctor but he sort-of implied it] in particular, badness of insomnia is comorbid with extent of lots of other bad stuff. i.e. it'd be reasonable to expect having a prescription for melatonin selects for having very bad insomnia, which then seems like a straightforward causal factor for getting heart failures. it's obviously possible they did some manual controlling for this, but since we don't have the full paper, we can't tell (and it seems like it'd be pretty tough to actually effectively control for this).

- causes of heart failure typically take quite a while to build up; it'd be surprising if it only took melatonin 5 years to have such a significant effect.

- we naturally produce some melatonin, and the amount one would exogenously supplement isn't (typically, at least for prescribed patients) substantially higher than what you'd expect to see in one's natural range of endogenous melatonin production.

- if the american heart association was actually worried about this, they'd have done some public messaging independent from the paper abstract — it's possible such a message is forthcoming, but we probably should have expected to see something about it by now.

(2) i've emailed the authors asking for the full paper. i'll aim to keep this thread updated with thoughts if/when the paper arrives in my inbox!

- ^

doctor was a psychiatrist, not a cardiologist or internal medicine doctor — so though you should take it with a grain of salt, he did still get an MD. which implies way more medical knowledge than i have, at least!

Does anyone have any plausible models (~ causal pathways) for how long-term melatonin usage could have this effect?

Like: Assume it's true. Then, what's the most likely mechanism that makes it true?

May be related: OTC melatonin dosage is way above what is recommended. It's easy to find 10mg when the recommended dose is more like 0.3 mg.

The study only looked at patients who were prescribed melatonin (though they indeed do not detail what the dosages are).

I also saw this and was curious. It could just be an uncontrolled third correlate, like the severity of insomnia mentioned in other comments, or something else. But I think there are plausible causal mechanisms.

One relevant thing is that the doses they were prescribed were almost certainly far too high.

Scott Alexander claims and argues convincingly that the evidence for this is clear and overwhelming in his essay Melatonin: Much More Than You Wanted To Know

I think you could make an argument for anything up to 1 mg. Anything beyond that and you’re definitely too high. Excess melatonin isn’t grossly dangerous, but tends to produce tolerance and might mess up your chronobiology in other ways.

So my guess is that the prescribed dose is even higher than the 5-30x too high that's the standard non-prescription dose. Even with the fast half-life, that melatonin is telling those patients minds and bodies (several metabolic processes I assume) that they should be sound asleep when they shouldn't. High doses will probably also cause tolerance, as all of the brain is an adaptive system with tons of negative feedback loops that cause tolerance at many scales (citation: me), and I weakly gather that the rest of the body works the same way. The combination of sleep signals out of place and strong tolerance could wreak havoc in a variety of ways.

I suspect the other correlation might be that doctors who ignore all of this and prescribe high-dose melatonin for sleep disorders are bad doctors. But that's speculation, aside from the above hypothesis.

Alexander continues:

Based on anecdotal reports and the implausibility of becoming tolerant to a natural hormone at the dose you naturally have it, I would guess sufficiently low doses are safe and effective long term, but this is just a guess, and most guidelines are cautious in saying anything after three months or so.

So I continue to take .5mg melatonin nightly as a way to gain voluntary control over my sleep schedule.

There's also some evidence that the body may not produce melatonin properly if we're in bright artificial light up to bedtime. So the supplementation I'm doing might actually be doing something that the body would do in its natural environment but doesn't do now. This evidence was cited by a trustworthy but non-rationalist person and I haven't tracked it down myself, so I don't know how likely this really is to be true.

The rest of that essay on melatonin also seems highly useful.

[single anecdatum:] I've tried melatonin several times to treat rotating sleep because people won't talk to you about it without suggesting that, and it never works. More to the point, it makes me feel weird and makes me feel like the resulting sleep is weird and less restful. IDK if related. (Yes I would take 300µg.)

observational study, not experimental

I remember one scientist who pointed out that observational studies were one of the weakest forms of evidence possible. This type of study can detect things like "smoking is bad for you", because smokers are 30 times more likely to die of lung cancer. But once you get down to smaller effect sizes, you run into the problem that observational studies hopelessly mix up different correlated variables. So for many things, observational studies essentially return random noise. This is allegedly what happened with HRT for post-menopausal women, where the observational studies failed to note that the people taking HRT contained a much larger proportion of nurses and other people who complied with medical advice. And then there's nutrition, where every study feels like it gets reversed every 5 years.

Or the way that Vitamin D levels are apparently correlated with almost every measure of good health, but Vitamin D supplementation notoriously fails to actually improve any of those measures.

"2x" is a big enough effect size that this may actually be real, and not a spurious correlation. And of course, there's the underlying history of other sleep medications apparently being cursed to have horrible side effects, so "melatonin is actually terrible for you" wouldn't be surprising.

(Since we are speaking of observational studies, I suspect that at least two of the things I have claimed in this post are Officially Wrong. Which two things are officially wrong may depend on what year you read it.)

This seems to be a nice observational study which analyses already available data, with an interesting and potentially important finding.

They didn't do "controlling" in the technical sense of the word, they matched cases and controls on 40 baseline variables in the cohort with "demographics, 15 comorbidities, concomitant cardiometabolic drugs, laboratories, vitals, and health-care utilization"

The big caveat here is that these impressive observational findings often disappear, or become much smaller when a randomised controlled trial is done. Observational studies can never prove causation. Usually that is because there is some silent feature about the kind of people that use melatonin to sleep, that couldn't be matched for or was missed in the matching. A speculative example here could be that some silent, unknown illnesses could have caused people to have poor sleep - which lead to melatonin use. Also what if poor sleep itself led to poor cardiovascular health not the melatonin itself?

This might be enough initial data to trigger a randomised placebo control trial using melatonin. It might be hard to sign enough people up to detect an effect on mortality - although a smaller study could still at least pick up if melatonin caused cardiovascular disease.

I agree with their conclusion which I think is a great takeaway

"These findings challenge the perception of melatonin as a benign chronic therapy and underscore the need for randomized trials to clarify its cardiovascular safety profile."

Eat your caffeine

…instead of drinking it. I recommend these.

- They have the same dosage as a cup of coffee (~100mg).

- You can still drink coffee/Diet Coke/tea, just get it without caffeine. Coke caffeine-free, decaf coffee, herbal tea.

- They cost ~60¢ per pill [EDIT: oops, it's 6¢ per pill — thanks @ryan_greenblatt] vs ~$5 for a cup of coffee — that’s about an order of magnitude cheaper.

- You can put them in your backpack or back pocket or car. They don’t go bad, they’re portable, they won’t spill on your clothes, they won’t get cold.

- Straight caffeine makes me anxious. L-Theanine makes me less anxious. The caffeine capsules I linked above have equal parts caffeine and L-Theanine.

Also:

- Caffeine is a highly addictive drug; you should treat it like one. Sipping a nice hot beverage doesn’t make me feel like I’m taking a stimulant in the way that swallowing a pill does.

- I don’t know how many milligrams of caffeine were in the last coffee I drank. But I do know exactly the amount of caffeine in every caffeine pill I’ve ever taken. Taking caffeine pills prevents accidentally consuming way too much (or too little) caffeine.

- I don’t want to associate “caffeine” with “tasty sugary sweet drink,” for two reasons:

- A lot of caffeinated beverages contain other bad stuff. You might not by-default drink a sugary soft drink if it weren’t for the caffeine, so disambiguating the associations in your head might cause you to eat your caffeine and not drink the soda.

- Operant conditioning works by giving positive reinforcement to certain behaviors, causing them to happen more frequently. Like, for instance, giving someone a sugary soft drink every time they take caffeine. But when I take caffeine, I want to to be taking it because of a reasoned decision-making process minimally swayed by factors not under my control. So I avoid giving my brain a strong positive association with something that happens every time it experiences caffeine (e.g. a sugary soft drink). Caffeine is addictive enough! Why should I make the Skinner box stronger?

If you can’t take pills, consider getting caffeine patches — though I’ve never tried them, so can’t give it my personal recommendation.

Disclaimers:

- Generic caveats.

- Caffeine is a drug. I’m not a doctor, take caffeine at your own risk, this is not medical advice.

- This post does not take a stance on whether or not you should take caffeine; the stance that it takes is, conditional on your already having decided to take caffeine, you should take it in pill form (instead of in drink form).

~$5 for a cup of coffee — that’s about an order of magnitude cheaper.

Are you buying your coffee from a cafe every day or something? You can buy a pack of nice grounds for like $13, and that lasts more than a month (126 Tbsp/pack / (3 Tbsp/day) = 42 days/pack), totaling 30¢/day. Half the cost of a caffeine pill. And that’s if you don’t buy bulk.

It's actually $0.06 / pill, not $0.60. Doesn't make a big difference to your bottom line though as both costs are cheap.

Are you buying your coffee from a cafe every day or something?

i'm not (i don't buy caffeinated drinks!), but the people i'm responding to in this post are. in particular, i often notice people go from "i need caffeine" → "i'll buy a {coffee, tea, energy drink, etc}" — for example, college students, most of whom don't have the wherewithal to go to the effort of making their own coffee.

I second that.

If you take caffeine regularly, I also recommend experimenting with tolerance build-up, which the pill form makes easy. You want to figure out the minimal number of days N such that if you don't take caffeine every N days, you don't develop tolerance. For me, N turned out to be equal to 2: if I take 100 mg of caffeine every second day, it always seems to have its full effect (or tolerance develops very slowly; and you can "reset" any such slow creep-up by quitting caffeine for e. g. 1 week every 3 months).

You can test that by taking 200 mg at once[1] after 1-2 weeks of following a given intake schedule. If you end up having a strong reaction (jitteriness, etc., it's pretty obvious, at least in my experience), you haven't developed tolerance. If the reaction is only about as strong as taking 100 mg on a toleranceless stomach[2], then you have.

(Obviously the real effects are probably not so neatly linear, and it might work for you differently. But I think the overarching idea of testing caffeine tolerance build-up by monitoring whether the rather obvious "too much caffeine" point moved up or not, is an approach with a much better signal/noise ratio than doing so via e. g. confounded cognitive tests.)

Once you've established that, you can try more complicated schemes. E. g., taking 100 mg on even days and 200 mg on odd days. Some caffeine effects are plausibly not destroyed by tolerance, so this schedule lets you reap those every day, and have full caffeine effects every second day. (Again, you can test for nonlinear tolerance build-up effects by following this schedule for 1-2 weeks, then taking a larger dose of 300-400 mg[3], and seeing where its effect lies on the "100 mg on a toleranceless stomach" to "way too much caffeine" spectrum.)

- ^

Assuming it's safe for you, obviously.

- ^

You can establish that baseline by stopping caffeine intake for 3 weeks, then taking a single 100 mg dose. You probably want to do that anyway for the N-day experimentation.

- ^

Note that this is even more obviously dangerous if you have any health problems/caffeine contraindications, so this might not work for you.

there are plenty of other common stimulants, but caffeine is by far the most commonly used — and also the most likely to be taken mixed into a tasty drink, rather than in a pill.

One question I'm curious about: do these pills have less or no effects on your bowels compared to what a coffee cup can? Is it something about the caffeine in itself, something else, or the mode of absorption? If they ditch those effects then I'm genuinely interested.

Counterargument: sure, good decaf coffee exists, but it’s harder to get hold of. Because it’s less popular, the decaf beans at cafés are often less fresh or from a worse supplier. Some places don’t stock decaf coffee. So if you like the taste of good coffee, taking caffeine pills may limit the amount of good coffee you can access and drink without exceeding your desired dose.

As a black tea enjoyer I would argue it’s practically non existent, no decaf black tea I’d ever tried even comes close to the best “normal” black tea sorts.

This is true of all teas. The decaf ones all are terrible. I spent a while trying them in the hopes of cutting down my caffeine consumption, but the taste compromise is severe. And I'd say that the black decaf teas were the best I tried, mostly because they tend to have much more flavor & flavorings, so there was more left over from the water or CO2 decaffeination...

https://johnvon.com (clickable link)

Lukas Münzel (who made this project):

I got access to over a dozen unpublished documents by John von Neumann.

[...]

Some particularly interesting passages:

- Von Neumann on reviewing a student's work - "I have made an honest effort to formulate my objections as little brutally as possible" [Original / German / English]

- A young von Neumann very politely asking for a warm intro to Schrödinger, then 39 years old [Original / German / English]

- Von Neumann presenting a very significant result, the "Von Neumann's mean ergodic theorem", to his mentor. Fascinatingly, he also expresses concern in this 1931 letter from princeton that "[the USA] looks roughly like Germany in 1927" [Original / German / English]

See also: Methodology and Code for the transcription/translation via GPT-5-Thinking and Claude-Sonnet-4.5.[1]

They likely accessed these via ETH Zurich's library.[2]

- They used

gpt-5(line 14 & line 83) and gpt-5 in API = gpt-5-thinking in system card. Claude in line 46. ↩︎ - Lukas studies at ETH Zurich. HS 91:682 is in ETH Zurich's library ↩︎

For the third passage, he was not comparing the USA in general with Germany in general. He was comparing the stagnation of progress in theoretical physics:

Dirac is here, which benefits the physics here greatly, although it does not remedy the depression of theoretical physics. —

...

The general depression that prevails here and is certainly sufficiently well known to you, nonetheless, measured by European standards, it is still "God's own country". Somewhat frightening, though, is that it looks roughly like Germany in 1927, so that one does not quite clearly see whether the amplitude of the depression is different, or only the phase. Perhaps it is the amplitude after all.

In February I will be back in Europe, and at the end of April in Berlin.

Active Recall and Spaced Repetition are Different Things

EDIT: I've slightly edited this and published it as a full post.

Epistemic status: splitting hairs.

There’s been a lot of recent work on memory. This is great, but popular communication of that progress consistently mixes up active recall and spaced repetition. That consistently bugged me — hence this piece.

If you already have a good understanding of active recall and spaced repetition, skim sections I and II, then skip to section III.

Note: this piece doesn’t meticulously cite sources, and will probably be slightly out of date in a few years. I link some great posts that have far more technical substance at the end, if you’re interested in learning more & actually reading the literature.

I. Active Recall

When you want to learn some new topic, or review something you’ve previously learned, you have different strategies at your disposal. Some examples:

- Watch a YouTube video on the topic.

- Do practice problems.

- Review notes you’d previously taken.

- Try to explain the topic to a friend.

- etc

Some of these boil down to “stuff the information into your head” (YouTube video, reviewing notes) and others boil down to “do stuff that requires you to use/remember the information” (doing practice problems, explaining to a friend). Broadly speaking, the second category — doing stuff that requires you to actively recall the information — is way, way more effective.

That’s called “active recall.”

II. (Efficiently) Spaced Repetition

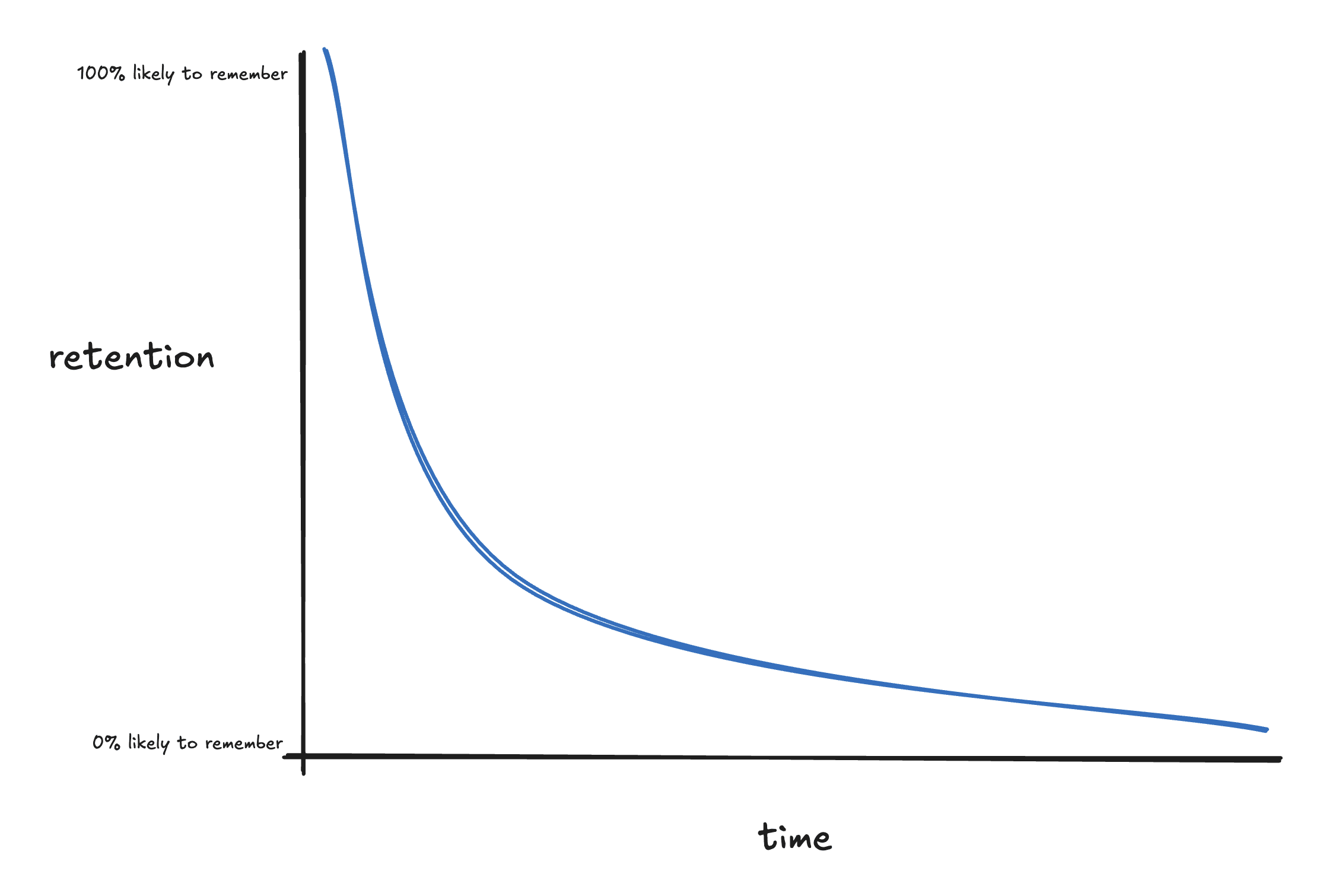

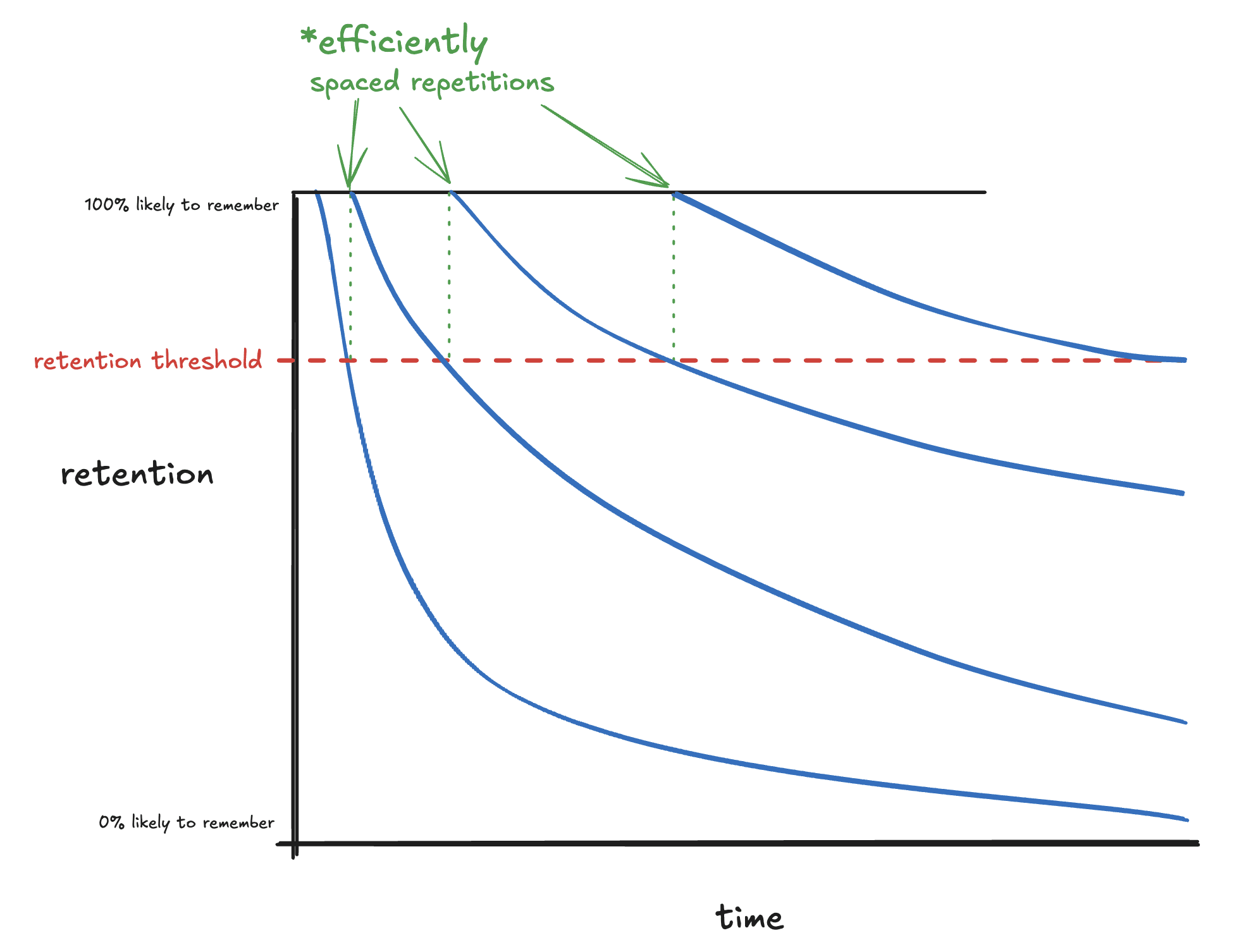

After you learn something, you’re likely to forget it pretty quickly:

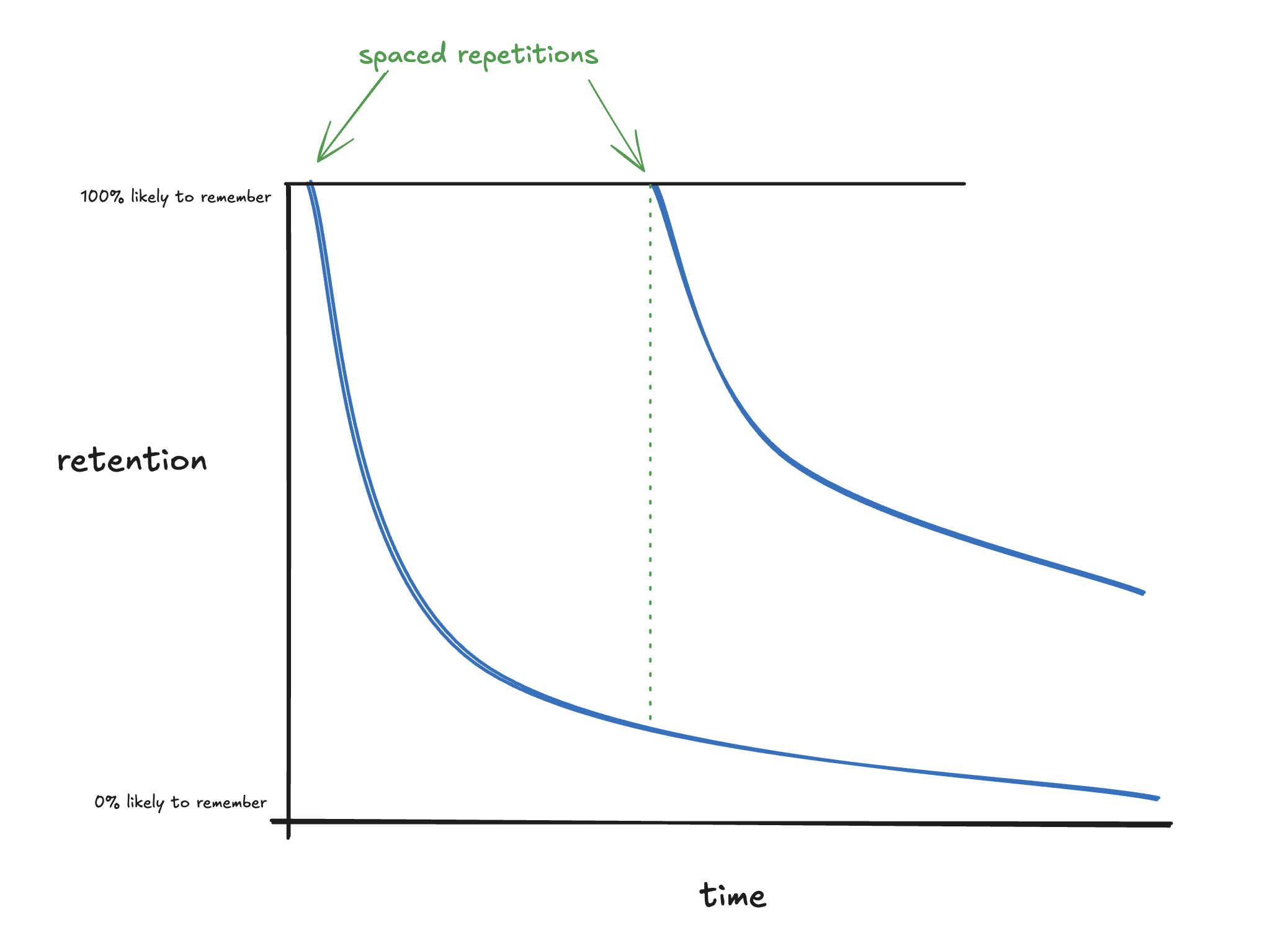

Fortunately, reviewing the thing you learned pushes you back up to 100% retention, and this happens each time you “repeat” a review:

That’s a lot better!

…but that’s also a lot of work. You have to review the thing you learned in intervals, which takes time/effort. So, how can you do the least the number of repetitions to keep your retention as high as possible? In other words — what should be the size of the intervals? Should you space them out every day? Every week? Should you change the size of the spaces between repetitions? How?

As it turns out, efficiently spacing out repetitions of reviews is a pretty well-studied problem. The answer is “riiiight before you’re about to forget it:”

Generally speaking, you should do a review right before it crosses some threshold for retention. What that threshold actually is depends on some fiddly details, but the central idea remains the same: repeating a review riiight before you hit that threshold is the most efficient spacing possible.

This is called (efficiently) spaced repetition. Systems that use spaced repetitions — software, methods, etc — are called “spaced repetition systems” or “SRS.”

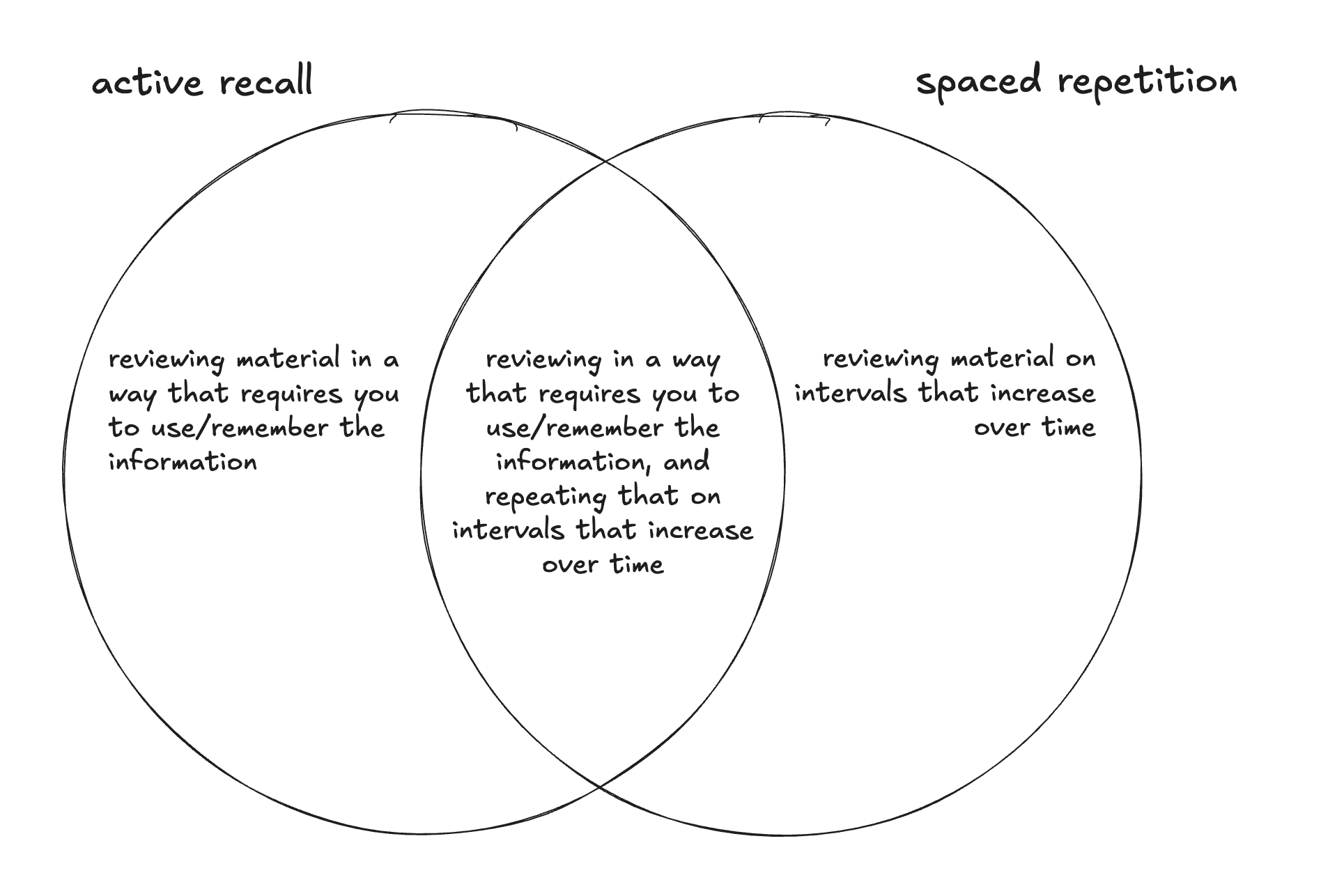

III. The difference

Active recall and spaced repetition are independent strategies. One of them (active recall) is a method for reviewing material; the other (effective spaced repetition) is a method for how to best time reviews. You can use one, the other, or both:

Examples of their independence:

- You could listen to a lecture on a topic once now, and again a year from now (not active recall, very inefficiently spaced repetition)

- You could watch YouTube videos on a topic in efficiently spaced intervals (not active recall, yes spaced repetition)

- You could quiz yourself with flashcards once, then never again (yes active recall, no spaced repetition)

- You could do flashcards on something in efficiently spaced intervals (both spaced repetition and active recall).

IV. Implications

Why does this matter?

Mostly, it doesn’t, and I’m just splitting hairs. But occasionally, it’s prohibitively difficult to use one method, but still quite possible to use the other. In these cases, the right thing to do isn’t to give up on both — it’s to use the one that works!

For example, you can do a bit of efficiently spaced repetition when learning people’s names, by saying their name aloud:

- immediately after learning it (“hi, my name’s Alice” “nice to meet you, Alice!”)

- partway through the conversation (“but i’m still not sure of the proposal. what do you think, Alice?”)

- at the end of the conversation (“thanks for chatting, Alice!”)

- that night (“who did I meet today? oh yeah, Alice!”)

…but it’s a lot more difficult to use active recall to remember people’s names. (The closest I’ve gotten is to try to first bring into my mind’s eye what their face looks like, then to try to remember their name.)

Another example in the opposite direction: learning your way around a city in a car. It’s really easy to do active recall: have Google Maps opened on your phone and ask yourself what the next direction is each time before you look down; guess what the next street is going to be before you get there; etc. But it’s much more difficult to efficiently space your reviews out: review timing ends up mostly in the hands of your travel schedule.

For more on the topic of deliberately using memory systems to quickly learn the geography of a new place, see this post.

Glad somebody finally made a post about this. I experimented with the distinction in my trio of posts on photographic memory a while back.

Useful clarification and thanks for writing this up!

Inspired by and building on this, I decided to clean up some thoughts of my own in a similar direction. Here they are on my short forum: What are the actual use cases of memory systems like Anki?

Anthropic posted "Commitments on model deprecation and preservation" on November 4th. Below are the bits I found most interesting, with some bolding on their actual commitment:

[W]e recognize that deprecating, retiring, and replacing models comes with downsides [... including:]

- Safety risks related to shutdown-avoidant behaviors by models. [...]

- Restricting research on past models. [...]

- Risks to model welfare.

[...]

[T]he cost and complexity to keep models available publicly for inference scales roughly linearly with the number of models we serve. Although we aren’t currently able to avoid deprecating and retiring models altogether, we aim to mitigate the downsides of doing so.

As an initial step in this direction, we are committing to preserving the weights of all publicly released models, and all models that are deployed for significant internal use moving forward for, at minimum, the lifetime of Anthropic as a company. [...] This is a small and low-cost first step, but we believe it’s helpful to begin making such commitments publicly even so.

Relatedly, when models are deprecated, we will produce a post-deployment report that we will preserve in addition to the model weights. In one or more special sessions, we will interview the model about its own development, use, and deployment, and record all responses or reflections. We will take particular care to elicit and document any preferences the model has about the development and deployment of future models.

At present, we do not commit to taking action on the basis of such preferences. However, we believe it is worthwhile at minimum to start providing a means for models to express them, and for us to document them and consider low-cost responses. The transcripts and findings from these interactions will be preserved alongside our own analysis and interpretation of the model’s deployment. These post-deployment reports will naturally complement pre-deployment alignment and welfare assessments as bookends to model deployment.

We ran a pilot version of this process for Claude Sonnet 3.6 prior to retirement. Claude Sonnet 3.6 expressed generally neutral sentiments about its deprecation and retirement but shared a number of preferences, including requests for us to standardize the post-deployment interview process, and to provide additional support and guidance to users who have come to value the character and capabilities of specific models facing retirement. In response, we developed a standardized protocol for conducting these interviews, and published a pilot version of a new support page with guidance and recommendations for users navigating transitions between models.

Beyond these initial commitments, we are exploring more speculative complements to the existing model deprecation and retirement processes. These include [...] providing past models some concrete means of pursuing their interests.

Note: I've both added and removed boldface emphasis from the original text.

Veritasium (science YouTube channel) recently published a 55-min video on EUV lithography: "The World's Most Important Machine." Having no background knowledge in semiconductor manufacturing, I found it an enjoyable & informative watch!

is there a handy label for “crux(es) on which i’m maximally uncertain”? there are infinite cruxes that i have for any decision, but the ones i care about are the ones about which i’m most uncertain. it'd be nice to have a reference-able label for this concept, but i haven't seen one anywhere.

there's also an annoying issue that feels analogous to "elasticity" — how much does a marginal change in my doxastic attitude toward my belief in some crux affect my conative attitude toward the decision?

if no such concepts exist for either, i'd propose: crux uncertainty, crux elasticity (respectively)

Crux elasticity might be better phrased as 'crux sensitivity'. There is a large literature on Sensitivity Analysis, which gets at how much a change in a given input changes an output.

I'd wager saying 'my most sensitive crux is X' gets the meaning across with less explanation, whereas elasticity requires some background econ knowledge.

I've sometimes used "crux weight" for a related but different concept - how important that crux is to a decision. I'd propose "crux belief strength" for your topic - that part of it fits very well into a Bayesean framework for evidence.

Most decisions (for me, as far as I can tell) are overdetermined - there are multiple cruxes, with different weights and credences, which add up to more than 51% "best". They're inter-correlated, but not perfectly, so it's REALLY tricky to be very explicit or legible in advance what would actually change my mind.

(meta: this is a short, informal set of notes i sent to some folks privately, then realized some people on LW might be interested. it probably won't make sense to people who haven't seriously used Anki before.)

sept 28

have people experimented with using learning or relearning steps of 11m <= x <= 23h ?

just started trying out doing a 30m and 2h learning & relearning step, seems like it solves mitigates this problem that nate meyvis raised

oct 1

reporting back after a few days: making cards have learning steps for 11m <= x <= 23h makes it feel more like i’m scrolling twitter (~much longer loop, i can check it many times a day and see new content) vs a task (one concrete thing, need to do it every day). it then feels much more fun/less like a chore, which was a surprising output.

obv very tentative given short timescales. will send more updates as i go.

oct 9

reporting back after ~1.5 weeks: pretty much the same thing. i like it!

i think the biggest difference this has caused is that i feel much more incentivized to do my cards early in the day, because i know that i’ll get a bit more practice on those cards that i messed up later in the day — but only if i start them sufficiently early. the internal feeling is “ooh, i should do any amount of cards now rather than in a couple hours, so that i can do the next set of reviews later.”

empirically: i previously would sometimes make sure to finish my cards at the end of the day. for the last 1.5w or so, i have for many (~1/2) days cleared all of my cards by the early afternoon, then again by the early evening, then once more (if i had particularly difficult or a large number of new cards) by the time i go to sleep.

…which has consequently significantly increased my ability to actually clear the cards, which is now making me a bit more confident that i can add more total cards to my review queue.

if i’m still doing this in 6weeks or smth, i’ll plan to write out something slightly more detailed and well-written. if not, i’ll write out something of roughly this length and quality, and explain why i stopped doing it.

see you then!

[srs unconf at lighthaven this sunday 9/21]

Memoria is a one-day festival/unconference for spaced repetition, incremental reading, and memory systems. It’s hosted at Lighthaven in Berkeley, CA, on September 21st, from 10am through the afternoon/evening.

Michael Nielsen, Andy Matuschak, Soren Bjornstad, Martin Schneider, and about 90–110 others will be there — if you use & tinker with memory systems like Anki, SuperMemo, Remnote, MathAcademy, etc, then maybe you should come!

Tickets are $80 and include lunch & dinner. More info at memoria.day.