I am conditionally in favor of human genetic augmentation. In particular, I think embryo selection for intelligence, health, happiness and other positive traits is desirable. When I bring this up with people, one of the most frequent questions is "Isn't that eugenics?"

I never know how to respond. The term "eugenics" has absorbed so much baggage over the last century that it somehow refers both to swiping right on Tinder when you see an attractive person and to the holocaust.

These are not similar concepts. The fact that we use a single word to refer to both is crazy. I cannot count the number of debates I've heard about human genetic engineering where the disagreement boils down to people misunderstanding what the other is advocating for. One person will talk about the benefits of improving the genes of future generations, and the other person will attack the idea because they mentally associate it with "eugenics", and to them that means "the holocaust" and "state sponsored sterilization of people with disabilities".

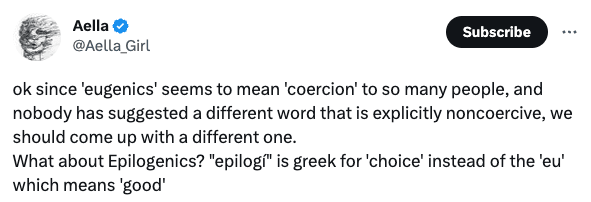

The fault lies with the term itself. It means so many different things to so many people that its use actively hinders understanding. For this reason, I think we should start using a new term to talk about non-coercive means of improving human genetics.

Epilogenics: non-coercive means of changing genetics

This term originated with Aella on Twitter, and I think it perfectly fits the purpose I have in mind.

Examples of epilogenics

- Selecting an embryo for lower disease risk, higher intelligence, or some other trait good for both the individual and society

- Gene editing for the purposes listed above

- Choosing an attractive spouse

Examples of things that are not epilogenics

- State-sponsored sterilization of people deemed “unfit”

- Rules against marriage of family members such a siblings and cousins

- Things people think of as eugenics even though they are often bad for genes (i.e. genocide)

I would encourage the use of this term to clarify the difference between genocide and screening one's embryos for desirable traits.

I do not see how that follows? The hypothetical, feared thing has actually happened, and they find it to be a lot less awful than they thought - they actually find that once they get the support and information they need and process the information, they are very happy. There always seems to be an initial shock, fear and overwhelm, but it appears that that tends to pass relatively quickly.

We could imagine a pressure to pretend to love your kid, as that is common, leading to an underreporting of regret.

But in that case, we could compare reports from parents of kids with Down syndrome being regretful with parents of kids without the syndrome being regretful.

In this context, the study "Regretting motherhood" comes to mind.

Can't find a version without a paywall, and it is qualitative research (I assume because lies are so expected), so we have no straightforward numbers to compare (unless she details the recruitment process?), but the summary of her interviews suggests that regret was not correlated with the health and personality of the children, but with whether the woman herself wanted children in general. If the woman did not want to become a mother, the child being healthy and lovely did not change that. But if she did want to become a mother, a child with Down syndrome still brought happiness.

Another thing one could look into is kids given up for adoption. This is certainly more common with Down syndrome in countries where the parents are poor, and receive no support with medical problems, and experience a lot of discrimination. Which is how these kids end up adopted out to families in countries with a decent security net and less discrimination.

There are also adoptions within the US; people whose kids have Down syndrome wanting to adopt them out, others wanting to adopt them, and parents who considered adopting them out, but kept them. Reading the reports, a recurring theme is that the parents are initially extremely fearful and aversive, but upon spending time with kids who have the condition and their parents, their opinion often changes.

Here is a report of a mother who got the diagnosis and freaked out, wanting to adopt out, but changed her mind after interacting with kids with the syndrome, and is glad she did: https://www.ndsan.org/adoption-stories/i-decided-to-parent/story-1/

Here is one of a woman who adopted out - the text makes it clear she grew very fond of the child after birth, but didn't think her life situation would make it possible for her to support a special needs child (she had only just met the father, they didn't want a long term relationship, etc.) Again, decent social support seems to make a difference; the concern isn't that they won't love the child, but that they won't manage to give it the support it needs https://www.ndsan.org/adoption-stories/i-made-an-adoption-plan/story-2/

And as for those who adopted - the process is a lengthy, complicated nightmare, they clearly really, really, really want those kids and are over the moon when they get them https://www.lovewhatmatters.com/we-found-our-phones-with-several-missed-calls-texts-congratulations-youve-been-matched-with-a-baby-boy-adoption-special-needs-family/ Again, a core theme is that they actually know people with the syndrome; the adoptive mother here had a cool uncle with down syndrome who was influential in her choice to want one.

No matter how you turn it - there seems to be a significant discrepancy between the number of parents who would chose against a child with down syndrome immediately and without any first hand experience, and those who have them and tend to actually be glad.