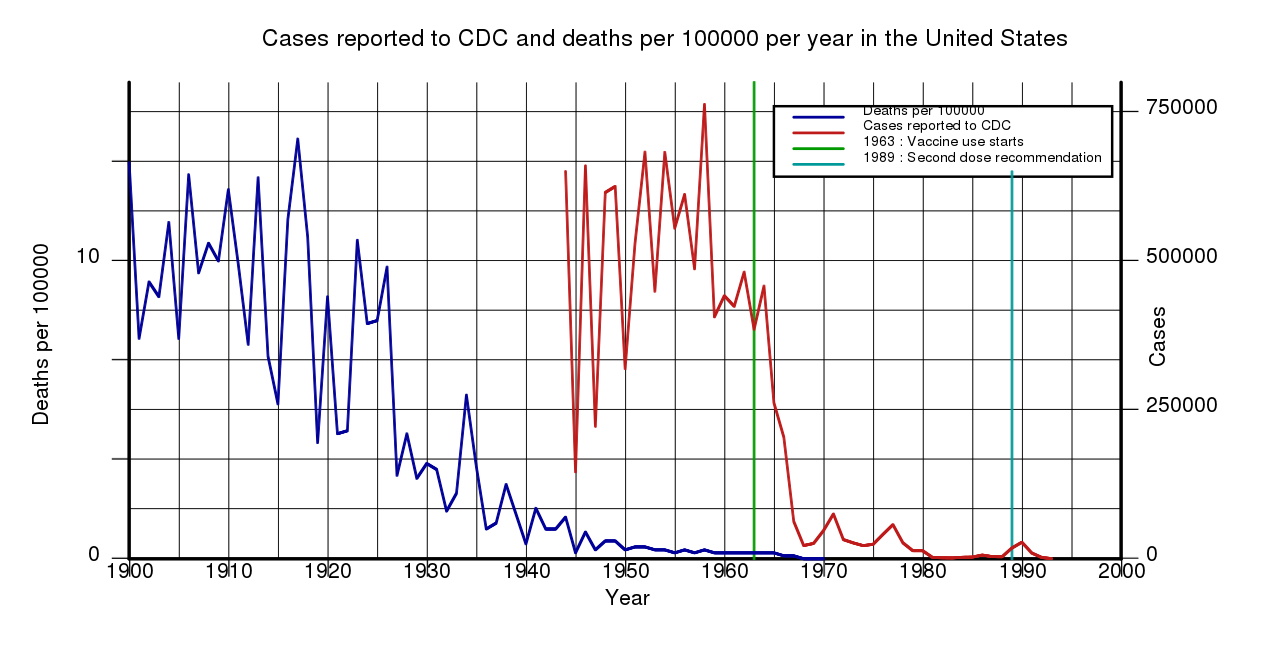

I believe that a much stronger statement is true. For almost every viral disease with a vaccine, there was a 90% reduction in mortality before the advent of the vaccine. The only graph I have on hand is measles:

Of course, if A causes a 90% reduction in mortality and B causes a 90% reduction in mortality, and they are independent, in a causal sense they are equal and you shouldn't judge their effects based on which one is deployed first. But once one is deployed, the marginal value of adding the other is only 10% as much. Even if B causes a 100% reduction, its marginal value beyond A is only 10% of the initial value of A.

(There is also a theory that measles resets your immune system and wipes out acquired immunity, so avoiding measles saves even more lives. So then a vaccine would be much more valuable than surviving measles.)

I've done more research since I wrote this. I'm not sure if this is true “for almost every viral disease with a vaccine”, but it might be true for many or most of them.

The big ones I know of where it's not true are smallpox and polio. Smallpox we don't have great data on because its vaccine was invented so early (1700s), but there's no reason to believe that its mortality rate was dropping significantly; in general big mortality rate drops didn't occur until later.

Polio we do have good data on, and it's clear that the epidemics continued, and indeed got worse, until the introduction of the vaccine in 1955. Polio is something of a special case in that it was not improved by sanitation.

Other diseases seem to have been ameliorated through sanitation, hygiene, and perhaps nutrition. I go into more detail on this in “Draining the swamp: How sanitation fought disease long before vaccines or antibiotics”.

TL:DR;

A vaccine skeptic on twitter believes "10% of the decline in infectious disease mortality in the 20th century in the US was due to vaccines."

I don't know, that's what some random anti-vaxxer on Twitter claimed. I'm still doing the quantitative investigation. My point is, even if that's true, it's misleading in isolation, and arguably cherry-picked

(Indirect) Attributions added.

10% still seems like a big deal to me, especially over a century. (What's the other 90% from, adopting a policy of washing hands?)

Fair enough. Again, I don't know if it's 10%—could be more or even less.

The rest, I think, is mostly from antibiotics, and maybe general hygiene.

The history and causation here is nuanced and difficult. E.g., tuberculosis was basically solved by antibiotics—*but*, it was also declining for many decades *before* that. And I'm not sure if anyone really knows why. Hand-washing? Better diet? Less spitting in the streets? (I'm not kidding, there were actually campaigns to get people to spit less, although I'm not sure if they worked.)

Anyway I'm still researching all this.

10% is a big deal but there are many different ways to persue better health outcomes and if we overrate particular approaches and underfund others that can be a problem.

At the moment we have 35 vaccine candiates in clinical evaluation for COVID-19 while on the other hand we have trouble spending 20 million to have decent studies on whether the top 8 most promissing antivirals helps with COVID-19.

I heard a vaccine skeptic claim that “90% of the decline in infectious disease mortality in the 20th century in the US was due to factors other than vaccines.” I wondered, is that right?

My guess is yes—but at the same time, I think this is very misleading. That statistic makes it sounds like vaccines just aren’t very important to health—sort of a sideshow in the fight against infectious disease. But here’s what the stat leaves out, and why vaccines still matter:

First, the greatest victory of vaccines was over smallpox. Smallpox vaccination was invented in 1796, and other immunization techniques were in use in England and America as early as 1721, so by 1900, immunization had already been fighting smallpox for well over 100 years. Smallpox is also the only disease we have ever completely eradicated—wiped off the face of the earth—and it was only possible because of vaccines. But by the 20th century, most of what remained to be done here was outside the US. So starting the clock in 1900, and restricting to the US, carves out most of the progress against smallpox.

Second, if we look just at the US in the 20th century, one of the greatest victories of vaccines was over polio. But the devastation of polio wasn’t just death—it was paralysis. Ten to twenty times more people were paralyzed by polio than died from it (especially after the “iron lung”). Unlike some other diseases, we weren’t able to fight polio with better sanitation or hygiene—in fact, it is believed that improved cleanliness caused the polio epidemics of the late 1800s and early 1900s. (Basically, before good sanitation, most people were exposed to polio in infancy, when they still had leftover immunity from their mothers, and when the disease is less likely to cause paralysis. Cleaner water led to a first exposure later in life, which led to a much worse disease.) So a vaccine was really our only weapon.

Third, in general, pharmaceuticals have been a bit ahead of vaccines. For some diseases, such as diphtheria and tuberculosis, an antitoxin or antibiotic was available before a vaccine was. This is also basically the story with influenza/pneumonia. Influenza is a viral disease that often results in an opportunistic infection of bacterial pneumonia. The pneumonia is what kills you. So antibiotics for pneumonia could reduce mortality ultimately caused by influenza. But just because these diseases could be treated with antibiotics (or antitoxins) doesn’t mean vaccines weren’t useful or valuable. Do you really want to wait to get a disease, and then treat it? Isn’t prevention better than cure? Are you totally fine with risking a potentially fatal infection just because drugs exist? What about resistant strains? And what would happen to antibiotic resistance, if we didn’t have vaccines and had to treat a much larger number of patients?

Fourth, looking only at mortality also simply ignores a variety of less common and/or less deadly diseases that are still important, such as chickenpox, hepatitis, mumps, rubella, and tetanus. True, these don’t add up to pneumonia or TB. But should we then just write them off?

Coming back to the original claim: Good data on these questions is non-trivial to come by and to analyze. But in the US in 1900, the top killers among infectious diseases were pneumonia, tuberculosis, various forms of gastrointestinal infections, and (distant fourth) diphtheria. The “90% not due to vaccines” claim is plausible to me because, for a variety of reasons, vaccines may not have been the first thing to drastically reduce mortality from these specific causes:

You could look at all those facts and say that vaccines are overrated. And perhaps antibiotics deserve the highest honors in the fight against infectious disease. But it would be a mistake to discount or dismiss vaccines, for the following reasons:

The vaccines the CDC recommends for routine immunization do not include diseases that have been successfully reduced by sanitation or pest control, such as yellow fever, typhoid fever, and cholera; or by eradication (smallpox); or those that are otherwise rare (anthrax). They basically only recommend vaccines that are highly effective or are for highly contagious diseases; in most cases both. The flu shot, which is only partially effective, and tetanus, which is not highly contagious, are both common enough in the US to be warranted.

Bottom line: the 90% claim is probably true, but:

I’m working on a better quantitative analysis to answer: which diseases were the worst, and which methods to fight them deserve most credit? I’ll post here when I have more info. In the meantime, if you have any pointers to good papers or data sources on this, let me know.