People who solve the problem, move on. People who can's solve the problem keep talking about it endlessly. Therefore the discussions about solving problems are dominated by people who have no clue what they are doing (because everyone else has already moved on).

The same applies to self-help groups. People who actually got their life together have no time for those.

Rational people do not comment on Less Wrong. (Unless it serves a specific purpose, e.g. advertising their product.)

EDIT:

The last paragraph was a half-joke, but the serious part is the following:

- for Eliezer, Less Wrong was a tool to get followers, collaborators, and funding

- for people who work in AI Safety, Less Wrong is a place to post about their research, get useful feedback, and maybe get more citations because it makes their research more visible

- for people who are new to Less Wrong, it is a place to learn a new way of thinking... but after a few months, it stops serving this purpose, so they either find a new purpose, or stay purposeless, or leave

- for people like me, Less Wrong is mostly a way to procrastinate -- but procrastination is not rational

See also this old Robin Hanson comment:

I have had this experience several times in my life; I come across clear enough evidence that settles for me an issue I had seen long disputed. At that point my choice is to either go back and try to persuade disputants, or to continue on to explore the new issues that this settlement raises. As Eliezer implicitly advises, after a short detour to tell a few disputants, I have usually chosen this second route. This is one explanation for the existence of settled but still disputed issues; people who learn the answer leave the conversation.

I feel like this post just slapped me in the face violently with a wet fish. I'm still reeling from the impact and trying to figure out how I feel about it.

There are a lot of solutions but they’re often too boring and not sensational enough for serious consideration. Solutions must be exciting and make the adopter look good, efficacy is secondary.

I broadly agree, but I think it's worth it to learn to distinguish scenarios where a simple solution is known from ones where it is not. We have, say, building design and construction down pat, but AGI alignment? A solid cure for many illnesses? The obesity crisis? No simple solution is currently known.

Yes, so long as one can tell the difference between a problem that is solved (construction, microprocessor design, etc.) and one that is not ("depressed? just stop being sad, it's easy")

Also, we might apply an unnamed razor: If a problem has a simple solution, everyone would already be doing it.

If a problem has a simple solution, everyone would already be doing it.

This is false, though.

Finding a simple solution can be very hard:

This is a special collection of problems that were given to select applicants during oral entrance exams to the math department of Moscow State University. These problems were designed to prevent Jews and other undesirables from getting a passing grade. Among problems that were used by the department to blackball unwanted candidate students, these problems are distinguished by having a simple solution that is difficult to find. Using problems with a simple solution protected the administration from extra complaints and appeals. This collection therefore has mathematical as well as historical value.

Likely true. The sorts of problems I was thinking about for the razor are ones that have had a simple solutions for a very long time - walking, talking, sending electrical current from one place to another, illuminating spaces, stuff like that.

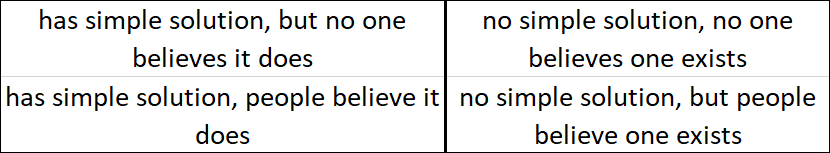

Perhaps a 2x2 grid would be helpful?

I feel like this post is standing against the top-left quadrant and would prefer everyone to move to the bottom-left quadrant, which I agree with. My concern is the people in the bottom-right quadrant, which I don't believe lukehmiles is in, but I fear they may use this post as fuel for their belief - i.e. "depression is easy, you attention-seeking loser! just stop being sad, it's a solved problem!"

This is a good post. I'm currently solving anthropic reasoning. And, oh boy, do I empathize with "all this shit is dumb, just do the obvious thing".

I think this post would've been even better if you didn't mix valid insights with humorous exaggerations.

You stop arguing about which of the equally baseless sampling assumptions is more or less ridiculous and just apply basic probability theory, instead, like with any other problem.

Except, you know, that's exactly what I do with Full Non-indexical Conditioning, but you don't like the answer.

Philosophy is full of issues where lots of people think they're just doing the "obvious thing", except these people come to different conclusions.

If you also felt "all this shit is dumb, just do the obvious thing" when you developed FNIC then I empathize with your feelings, while respectfully disagreeing with you on the objective level, regarding the question whether you are just applying basic probability theory or not.

Absolutely not fascinating answer. My brain is popping with "oh that makes sense ok". I have nothing to add and nothing to offer you. I will never think about this again. Unless I need to do some anthropic reasoning for some reason, in which case I will just apply basic probability theory and never thank you.

This reminds me of the observation that most things on the internet are written by insane people - empirically for most forms of media, including user-produced media, a few exceptional users contribute a supermajority of the output. And to be this exceptional you are likely to differ from the population in a lot of other ways as well.

The correct answer leaves nothing to be said. The wrong answer starts a conversation, a research program, an investigation, a journey, an institute, a paper, a book, a youtube channel, a lifestyle, a tribe.

Why is reading a textbook so boring? Very few people do it. It just has right answers and few great questions to ponder. Blogs arguing about nutrition are great reading though.

If you write a research paper saying "all that shit is dumb just do the obvious thing" then you'll probably have trouble getting it published. I tried once but my professor shut it down saying it's a bad strat basically.

"Clean energy" is great as a conversation piece or phrase in your mission statement but "just deregulate nuclear lmao why are you wasting your time" is definitely not in my experience.

It's fine if bad ideas are all we ever talk about but the trouble comes when it's time for someone to sit down and do their work. The doctor trying to cure a thing mostly heard about the RCTs on all the shitty methods that barely do anything, so they pick their favorite of those. The AI safety implementer mostly heard discussions about bad methods and probably tries to patch one of those. (And fixing the mistake in a bad method is a not a good way to make a good method.) The parents in the parent group of course mostly talk about their failed attempts to fix the problems they do have (and mostly forget about the problems they never had or quickly fixed) so the parents go home and try the mediocre ideas.

Have hope, you can combat wrong answer bias with these simple tricks.