I'm a programmer who's into startups. For my first startup, a site that provided student super in depth student reviews of colleges, I remember asking what people thought. I'd get all of these really encouraging responses. "Oh, that's so cool! I wish that existed when I was applying! That's gonna be so helpful to prospective students!"

Then for my second startup, I had similar experiences. I built an app that helps people study poker and received lots of great feedback. But for both startups, when it actually came time to sign up: crickets. When it actually came time to fork over some money: crickets.

The lesson? Talk is cheap. Actions speak louder than words. It's all about the Benjamins. That sort of stuff.

Now I work as a programmer in a large organization. Things are very different.

My team builds a tool that is used by many other teams in the organization. We don't, in my opinion, do a very good job of, before building a feature, checking to see if it truly addresses a pain point, and if so, how large that pain point is.

As an entrepreneur, if you do a poor job of this, you fail. You don't make money. You don't eat. Survival of the fittest. But in a large organization? It doesn't really matter. You still get your paycheck at the end of the day. There's no feedback mechanism. Well, I guess there is some feedback mechanism, but it's not nearly as strong as the feedback mechanism of having users voluntarily open up their own wallets and handing you money for the thing you're providing to them.

It reminds me of socialism. In socialism, from what I understand, there is a centrally planned economy. Some pointy-haired bosses decide that this group of people will produce this widget, and that group of people will produce that widget. If you do a clearly horrible job of producing the widget, you'll get fired. If you do a clearly incredible job, and respect the chain of command, you'll get promoted. But almost always, you'll just walk away with your paycheck. It doesn't matter too much how good of a job you do.

Well, sometimes it does. Sometimes there's more elasticity with who gets fired and who gets promoted. But even in those scenarios, it's highly based on KPIs that are legible.

I've been watching The Wire recently, and the show revolves around this a lot. Teachers having their students memorize things for the test. Police officers prioritizing quantity over quality in their arrests. Lawyers not taking cases that'd hurt their win percentage. Politicians wanting to do big and flashy things like building stadiums that look good to voters. But, of course, things that are legible are often not a very good proxy for things that matter.

I'm just babbling here. These aren't refined thoughts. I'm not someone who knows much about management, organizations, politics or socialism. But I wonder: is this a useful frame? Is it one that people already look at things through? How common is it? Does it point towards any solutions? What if large organizations had some sort of token economy where teams had a limited budget of tokens and used them to get access to various internal tools? What if they just used real money?

(image by

(image by

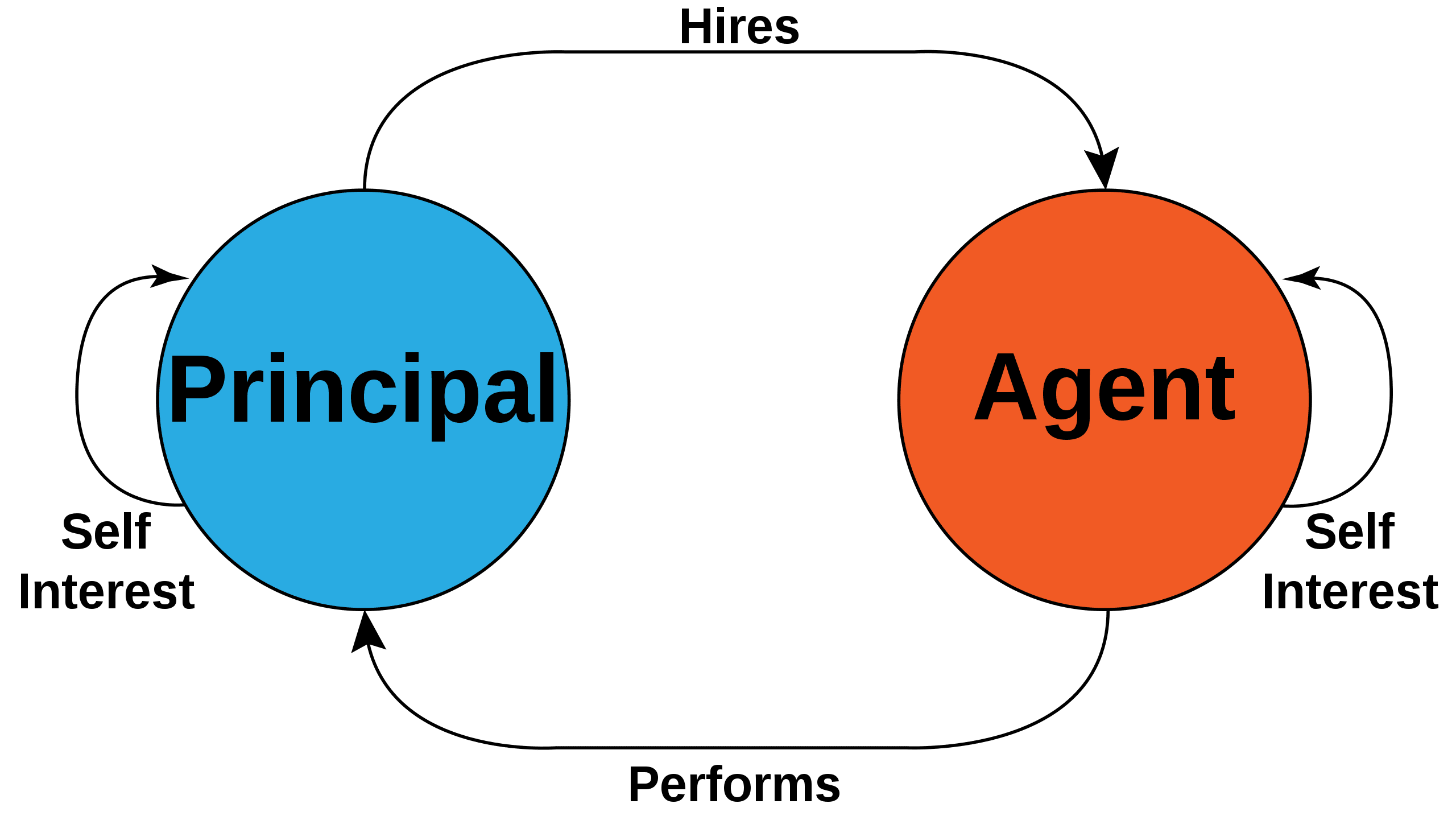

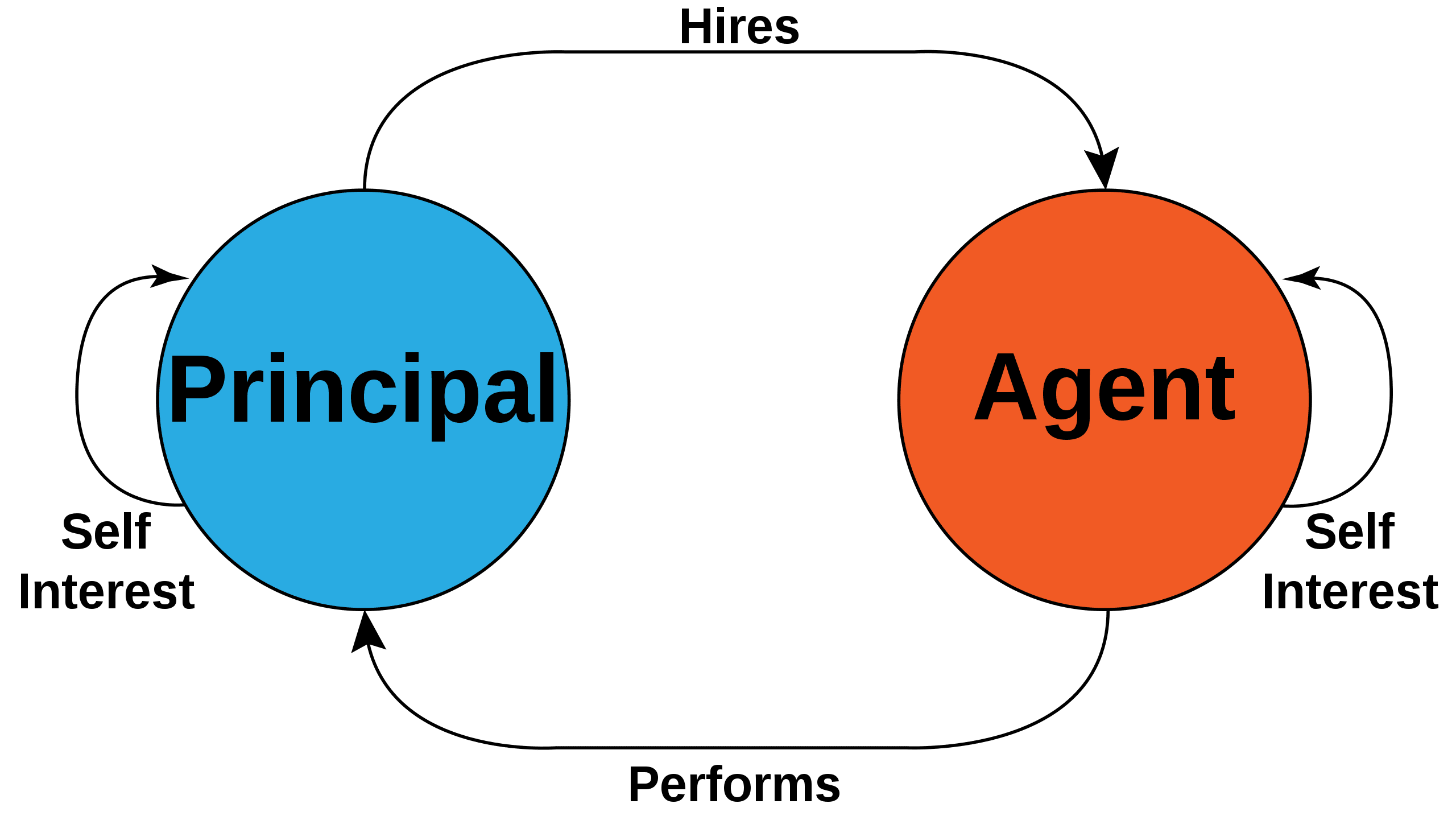

This problem has been studied extensively by economists within the field of organizational economics, and is called the principal-agent problem (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). In a principal-agent problem a principal (e.g. firm) hires an agent to perform some task. Both the principal and the agent are assumed to be rational expected utility maximisers, but the utility function of the agent and that of the principal are not necessarily aligned, and there is an asymmetry in the information available to each party. This situation can lead the agent into taking actions that are not in the principal's interests.

(image by Zirguezi)

(image by Zirguezi)

As the OP suggests, incentive schemes, such as performance-conditional payments, can be used to bring the interests of the principal and the agent into alignment, as can reducing information asymmetry by introducing regulations enforcing transparency.

The principal-agent problem has also been discussed in the context of AI alignment. I have recently written a working-paper on principal-agent problems that occur with AI agents instantiated using large-language models; see arXiv:2307.11137.

References

Jensen and W. H. Meckling, “Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership

structure,” Journal of Financial Economics 3 no. 4, (1976) 305–360

S. Phelps and R. Ranson, "Of Models and Tin Men - a behavioural economics study of principal-agent problems in AI alignment using large-language models", arXiv:2307.11137, 2023.

The main problems are the number of contracts and the relationship management problem. Once upon a time drawing up and enforcing the required number of contracts would have been prohibitevly expensive in terms of fees for lawyers. In the modern era Web 3.0 promised smart contracts to solve this kind of problem. But smart contracts don't solve the problem of incomplete contracts https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Incomplete_contracts, and this in itself can be seen as a transaction cost in the form of a risk premium. and so we are stuck with companies. In ... (read more)