When transit gets better the land around it becomes more valuable: many people would like to live next to a subway station. This means that there are a lot of public transit expansions that would make us better off, building space for people to live and work. And yet, at least in the US, we don't do very much of this. Part of it is that the benefits mostly go to whoever happens to own the land around the stations.

A different model, which you see with historical subway construction or Hong Kong's MTR, uses the increase in land value to fund transit construction. The idea is, the public transit company buys property, makes it much more valuable by building service to it, and then sells it.

While I would be pretty positive on US public transit systems adopting this model, I have trouble imagining them taking it on. Instead, consider something simpler and more distributed: private developers paying to expand public transit.

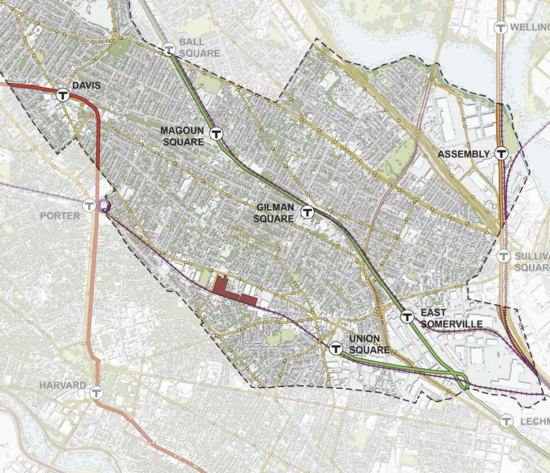

Consider the proposed Somernova Redevelopment, in Somerville MA:

This is a proposed $3.3B 1.9M-sqft development, adjacent to the Fitchburg Line. A train station right next to it would make a ton of sense, and could be done within the existing right of way without any tunneling. Somernova briefly mentions this idea on p283, where they say:

Introducing a new train station on campus could dramatically reduce commute times, making all of Somernova within a five minute walk from the station. We look forward to ongoing dialog about these transit possibilities with the community and advocates, ensuring we continue to explore all options for enhanced connectivity longterm.

This is pretty vague compared to the rest of the plan, which has a ton of estimates, but we can make our own. The MBTA recently completed a long and expensive project to extend the Green Line along this right of way, which stops at Union Square. Extending it to Dane Street would require another 0.9km of track and another station. The overall Green Line extension cost $2.2B for 7.6km, or $290M/km, though this included a bunch of over-designed work that needed to be thrown away and it should have been far less. This portion is relatively simple compared to the other work, with no maintenance facility or elevated sections, though it does include three bridges and moving a substation. Accepting the $290M/km figure, though, we could estimate $260M.

A $260M extension would raise Somernova's construction costs by under 8%, less if you include the costs of the land, and I expect would raise the value of the completed project by well more than that—rents right next to subway stations are generally a lot higher than farther away. So even though Somernova would not capture all of the benefits of the new station they would capture enough to come out ahead.

This isn't a new idea: in 2011 the Assembly Row developers made a deal with the MBTA to fund an infill station for their development. Because this was just a station it was cheaper: $15M from the developer and $16M from the federal government.

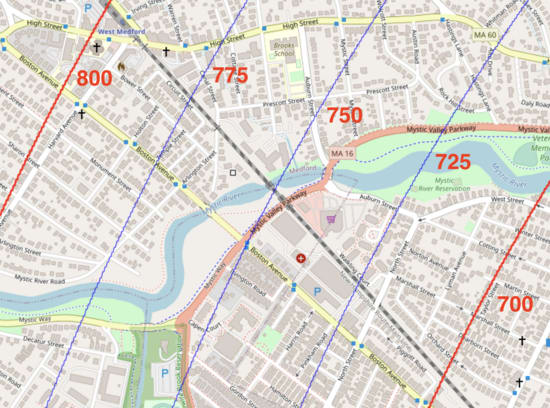

Another place where something like this could make sense is building housing at Route 16. The other branch of the Green Line Extension, along the Lowell Line, could be extended 1.4km to Route 16. Figuring the same $290M/km this would be $400M, though as a straight-forward project in an existing right of way it should be possble to do it for about half that. Next to the site is a liquor store and supermarket, about 150k sqft:

Let's say you build ground-floor retail (with more than enough room for the current tenants) and many stories of housing above it. It's not currently zoned for this, but zoning is often dependent on transit access and this is something the city could fix (ex: Assembly Square got special zoning). A hard limit on height is Logan Airport airspace but that's high enough you wouldn't come close:

The airspace rules would allow a ~65 story building, but lets say you pattern this off Assembly and go for 23 stories: 22 housing, one retail. With 75% average lot coverage (courtyards) this would be ~2.6M sqft. Building this might cost $600/sqft (but I'd love better numbers), giving ~$1.6B.

There's also a UHaul lot next door, at around 110k sqft which could be included:

Building it out the same way would give you another ~1.9M sqft at a cost of ~$1.1M, for a total of 4.5M sqft for $2.7B. Add in the subway extension and it's $3.1B.

Even with the cost of the extension this would be quite profitable: new construction right next to a subway station. Factoring in 20% for affordable housing, you break even at around $850/sqft, and extrapolating from the listings I see for Assembly you should be able to get about $1,000/sqft.

I'm not sure why we don't see more of this. Are transit agencies not very open to it? Are the costs too unpredictable? Are private developers too car-focused? Am I wrong about how much more valuable transit access makes places? Are cities unwilling to agree to high density for newly transit-served locations?

Ok, let's stick to this notion of expected value because it plays both for the land owner and for the transit system builder.

To get back to your post, the plan was to buy an area, build a transit system in the middle of it, then sell the rest at a higher price. If you fail to buy all the land you need (or at least enough of it), you may give up on the project, in which case the value of the land does not increase. So indeed, as the transit system builder, the viability of your project (and the profit attached to it) is linked to the probability that you indeed acquire the land you need (both the land to physically build the transit system and the land around to sell later at a higher price), as well as the price at which you will be able to buy the land first, and re-sell it after completion.

Now, if the land owner are correctly calibrated, and they correctly anticipate the odds of your project being a success, your expected profit on the sale of the land must be zero.

If, on the flip side, you expect to make a profit because the land owners will underestimate your ability to succeed, will not see you coming, not understand what you are trying to do, or something along those lines, then your strategy relies on the market not being efficient. If this is the case, I think this is a crux.