Race Along Rashomon Ridge

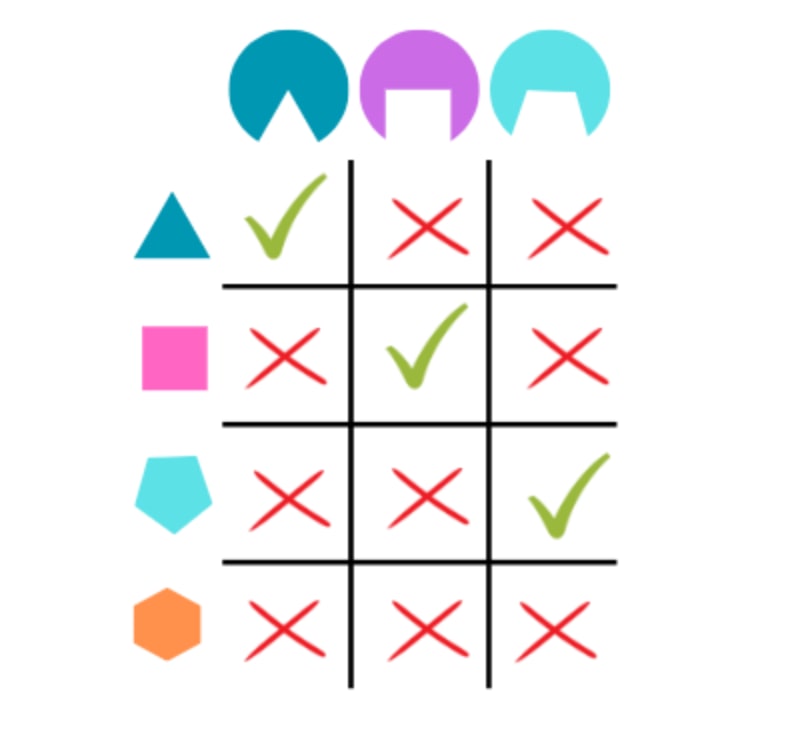

Produced As Part Of The SERI ML Alignment Theory Scholars Program 2022 Research Sprint Under John Wentworth Two Deep Neural Networks with wildly different parameters can produce equally good results. Not only can a tweak to parameters leave performance unchanged, but in many cases, two neural networks with completely different weights and biases produce identical outputs for any input. The motivating question: Given two optimal models in a neural network's weight space, is it possible to find a path between them comprised entirely of other optimal models? In other words, can we find a continuous path of tweaks from the first optimal model to the second without reducing performance at any point in the process? Ultimately, we hope that the study of equivalently optimal models would lead to advances in interpretability: for example, by producing models that are simultaneously optimal and interpretable. Introduction Your friend has invited you to go hiking in the Swiss Alps. Despite extensive planning, you completely failed to clarify which mountain you were supposed to climb. So now you're both currently standing on different mountaintops Communicating via yodels, your friend requests that you hike over to the mountain he's already on; after all, he was the one who organised the trip. How should you reach your friend? A straight line path would certainly work, but it's such a hassle. Hiking all the way back down and then up another mountain? Madness. Looking at your map, you notice there's a long ridge that leaves your mountain at roughly the same height. Does this ridge lead to reach your friend's mountain and is it possible to follow this ridge to reach your friend? Similarly, we can envision two optimal models in a neural net's weight space that share a "ridge" in the loss landscape. There is a natural intuition that we should be able to "walk" between these two points without leaving the ridge. Does this intuition hold up? And what of two neural net

I'd previously worked through a dozen or so chapters of the same Woit textbook you've linked as context for Representation Theory.

Given some group G, a (limear) "representation" is a homomorphism from G into the GL(V) the general linear group of some vector space.

That is, a map π:G→GL(V) is a representation iff for all elements g,h∈G,π(gh)=π(g)π(h).

Does "preferences between deals dependant on unknown world states" have a group structure? If not it cannot be a representation in the sense meant by Woit.