DeepMind: The Podcast - Excerpts on AGI

DeepMind: The Podcast - Season 2 was released over the last ~1-2 months. The two episodes most relevant to AGI are: * The road to AGI - DeepMind: The Podcast (S2, Ep5) and * The promise of AI with Demis Hassabis - DeepMind: The Podcast (S2, Ep9) I found a few quotes noteworthy and thought I'd share them here for anyone who didn't want to listen to the full episodes: The road to AGI (S2, Ep5) (Published February 15, 2022) Shane Legg's AI Timeline Shane Legg (4:03): > If you go back 10-12 years ago the whole notion of AGI was lunatic fringe. People [in the field] would literally just roll their eyes and just walk away. [...] [I had that happen] multiple times. I have met quite a few of them since. There have even been cases where some of these people have applied for jobs at DeepMind years later. But yeah, it was a field where you know there were little bits of progress happening here and there, but powerful AGI and rapid progress seemed like it was very, very far away. [...] Every year [the number of people who roll their eyes at the notion of AGI] becomes less. Hannah Fry (5:02): > For over 20 years, Shane has been quietly making predictions of when he expects to see AGI. Shane Legg (5:09): > I always felt that somewhere around 2030-ish it was about a 50-50 chance. I still feel that seems reasonable. If you look at the amazing progress in the last 10 years and you imagine in the next 10 years we have something comparable, maybe there's some chance that we will have an AGI in a decade. And if not in a decade, well I don't know, say three decades or so. Hannah Fry (5:33): > And what do you think [AGI] will look like? [Shane answers at length.] David Silver on it being okay to have AGIs with different goals (??) Hannah Fry (16:45): > Last year David co-authored a provocatively titled paper called Reward is Enough. He believes reinforcement learning alone could lead all the way to artificial general intelligence. > > [...] (21:37) > > But not everyo

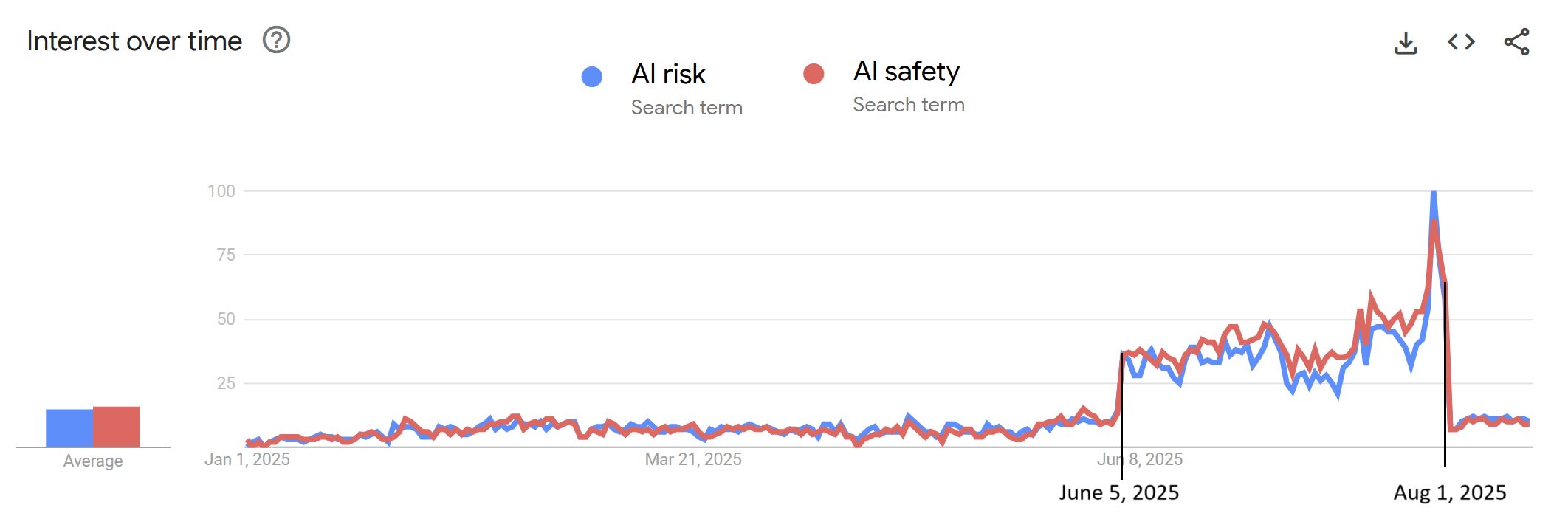

Joe tweet from Nov 5th: