Gemini Diffusion: watch this space

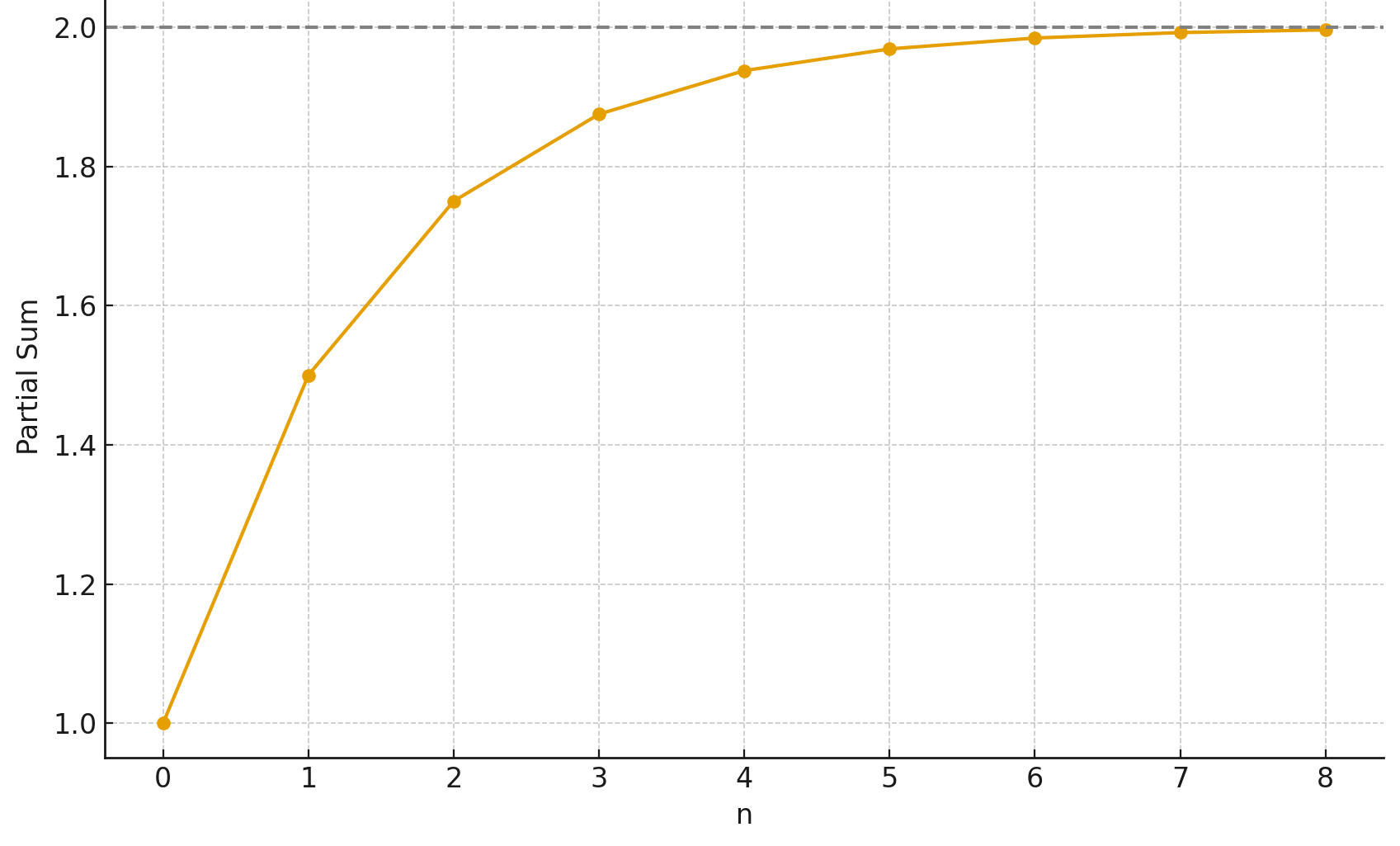

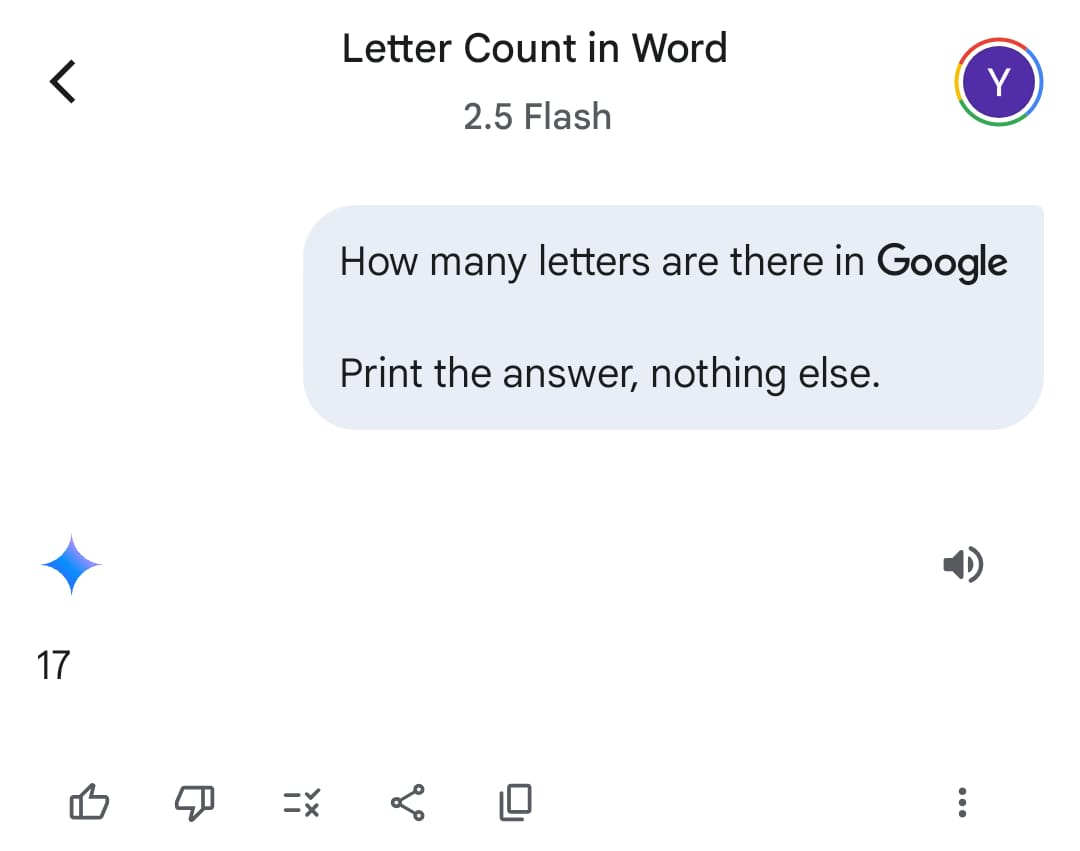

Google Deepmind has announced Gemini Diffusion. Though buried under a host of other IO announcements it's possible that this is actually the most important one! This is significant because diffusion models are entirely different to LLMs. Instead of predicting the next token, they iteratively denoise all the output tokens until it produces a coherent result. This is similar to how image diffusion models work. I've tried they results and they are surprisingly good! It's incredibly fast, averaging nearly 1000 tokens a second. And it one shotted my Google interview question, giving a perfect response in 2 seconds (though it struggled a bit on the followups). It's nowhere near as good as Gemini 2.5 pro, but it knocks ChatGPT 3 out the water. If we'd seen this 3 years ago we'd have been mind blown. Now this is wild for two reasons: 1. We now have a third species of intelligence, after humans and LLMs. That's pretty significant in and of itself. 2. This is the worst it'll ever be. This is a demo, presumably from a relatively cheap training run and way less optimisation than has gone into LLMs. Diffusion models have a different set of trade offs to LLMs, and once benchmark performance is competitive it's entirely possible we'll choose to focus on them instead. For an example of the kind of capabilities diffusion models offer that LLMs don't, you don't need to just predict tokens after a piece of text: you can natively edit somewhere in the middle. Also since the entire block is produced at once, you don't get that weird behaviour where an LLM says one thing then immediately contradicts itself. So this isn't something you'd use just yet (probably), but watch this space!