The standard view of the fall of the Roman Empire is horrifying and deeply troubling. A long time ago, there was a prosperous empire. They created advanced technology and complex philosophy. After existing for many centuries, violent barbarians invaded, ending the prosperity and ushering in The Dark Ages. Knowledge and technology was lost and civilization disappeared. After a thousand years of depressing mud hovels and Viking raids, the Renaissance happened - the rebirth of the classical world and the start of our modern era.

It's frightening, because it demonstrates that progress isn't inevitable. We are not guaranteed to continously get more wealthy, more peaceful and more civilized. Setbacks do happen, and they doom many millions of human beings to live horrible lives that could have been avoided.

As someone who did have a strong believe in 'Progress', this unsettled me. I had all kinds of questions. How do you lose knowledge and technology? How do you "uninvent" things? How did a bunch of unorganized, primitive barbarians defeat a civilization that was way more advanced than them? For many years, I studied the subject, spoke with leading experts and got access to the most recent data. Things merely became more confusing.

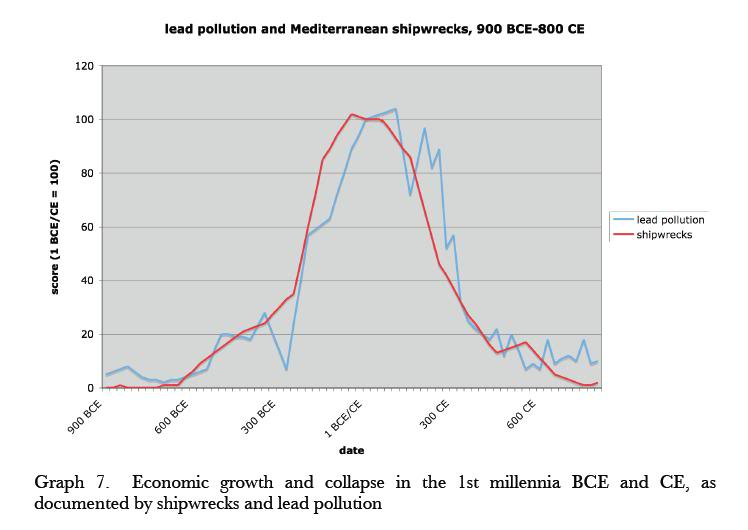

Lots of historians and archaeologists have made graphs presenting their findings from the Roman era. The same curve returns over and over again. Here it is:

It's extraordinary. Things start out at very low levels, nearly zero, and in the centuries before 1AD, they suddenly rise dramatically. They peak somewhere in or around the first century AD, and then decline again with the same pace. In 476, when the last Western Roman Emperor is deposed by a Germanic chieftain, little had been left of the former Roman economic activity. Europe becomes quiet once again.

It does make sense. Although classical Rome lasted from 753BC to 476AD, all the things it's famous for concentrate in the area around the peak in the graph. The Colosseum was completed in 80AD; the Pantheon was built between 113 and 125AD; Julius Ceasar died in 44BC; Pliny the Elder died in 79AD; the Pont du Gard was constructed between 40 and 60AD.

In my opinion, the standard narrative surrounding the rise and fall of ancient Rome has not properly integrated these new datasets. It barely explains the wealth of Rome, seeing it as relatively stable and the result of centuries of progress (and progress doesn't have to be explained; it just happens, like it does today). It explains the fall of Rome with the spread of some diseases, pressure by barbarians and 'corruption and decadence'.

For me, it's not convincing. It completely ignores the "shape of the curve", the sudden explosion of wealth and the equally quick decline afterwards. It assumes a prosperous Rome defeated by barbarians in the fifth century - not a hugely declined Rome that was merely a shell of its former self.

So, when the advanced Roman Empire came under pressure from plague and barbarians, it collapsed, and led to a thousand years of stagnation.

When medieval Europe came under pressure from the Black Death and Genghis Khan - ...it prospered? Explanations about how a decline in the population led to increased wages leading to progress abound.

Ian Morris is a historian and archeologist who is an expert in the ancient Mediterranean world and wrote a book analyzing all of world history. He measured/estimated the most advanced Western and Eastern civilizations in four aspects:

- Energy Capture

- City Size

- War-Making Capacity

- Information Technology

When you combine the scores for all these civilizations in one graph, you get this image:

As you can see, there has been a steady progress through the millenia, with a sudden exponential explosion at the end. That might be surprising to many, but I did not find it very strange. What I did find strange was the fact that there was only one serious, long-term decline: the Fall of Rome, followed by the Medieval Period.

The more I learned, the more confused I became.

- Why did the Roman economy suddenly explode and why did it decline just as rapidly?

- Why do 'barbarians' and diseases boost progress in the Medieval Period (just as WWII is seen as a period of rapid technological progress) while the same things are seen as valid causes for a thousand years of stagnation in the Roman era?

- Why is steady, long-term progress so stable in almost all eras, except the Post-Roman one?

After mulling it over, I think I found some very useful theories that answer these questions. I've investigated them further and all the answers I found fit my predictions. I want to explain my findings, and would love to hear your feedback. I intent to continue this story in the next post.