Back in December, I asked how hard it would be to make a vaccine for oneself. Several people pointed to radvac. It was a best-case scenario: an open-source vaccine design, made for self-experimenters, dead simple to make with readily-available materials, well-explained reasoning about the design, and with the name of one of the world’s more competent biologists (who I already knew of beforehand) stamped on the whitepaper. My girlfriend and I made a batch a week ago and took our first booster yesterday.

This post talks a bit about the process, a bit about our plan, and a bit about motivations. Bear in mind that we may have made mistakes - if something seems off, leave a comment.

The Process

All of the materials and equipment to make the vaccine cost us about $1000. We did not need any special licenses or anything like that. I do have a little wetlab experience from my undergrad days, but the skills required were pretty minimal.

The large majority of the cost (about $850) was the peptides. These are the main active ingredients of the vaccine: short segments of proteins from the COVID virus. They’re all <25 amino acids, so far too small to have any likely function as proteins (for comparison, COVID’s spike protein has 1273 amino acids). They’re just meant to be recognized by the immune system: the immune system learns to recognize these sequences, and that’s what provides immunity.

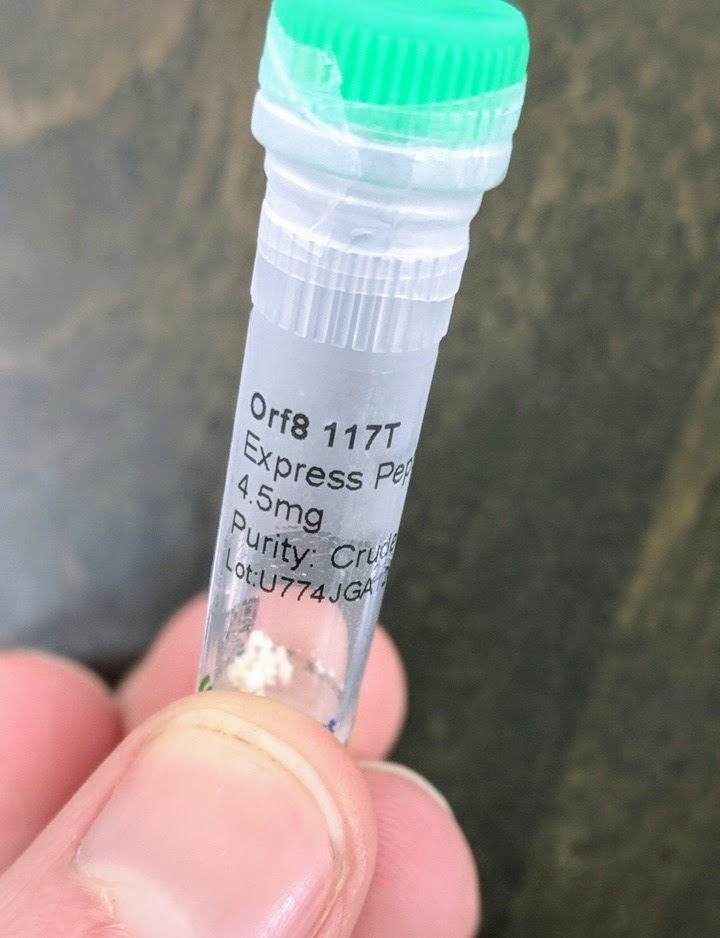

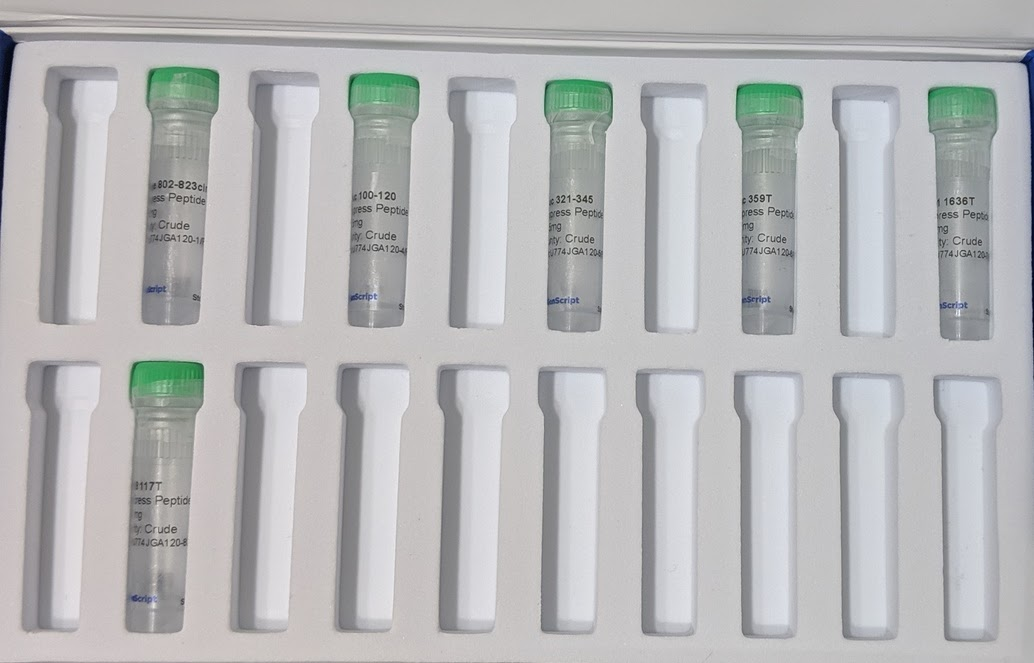

The peptides were custom synthesized. There are companies which synthesize any (short) peptide sequence you want - you can find dozens of them online. The cheapest options suffice for the vaccine - the peptides don’t need to be “purified” (this just means removing partial sequences), they don’t need any special modifications, and very small amounts suffice. The minimum order size from the company we used would have been sufficient for around 250 doses. We bought twice that much (9 mg of each peptide), because it only cost ~$50 extra to get 2x the peptides and extras are nice in case of mistakes.

The only unusual hiccup was an email about customs restrictions on COVID-related peptides. Apparently the company was not allowed to send us 9 mg in one vial, but could send us two vials of 4.5 mg each for each peptide. This didn’t require any effort on my part, other than saying “yes, two vials is fine, thankyou”. Kudos to their customer service for handling it.

Besides the peptides, all the other materials and equipment were on amazon, food grade, in quantities far larger than we are ever likely to use. Peptide synthesis and delivery was the slowest; everything else showed up within ~3 days of ordering (it’s amazon, after all).

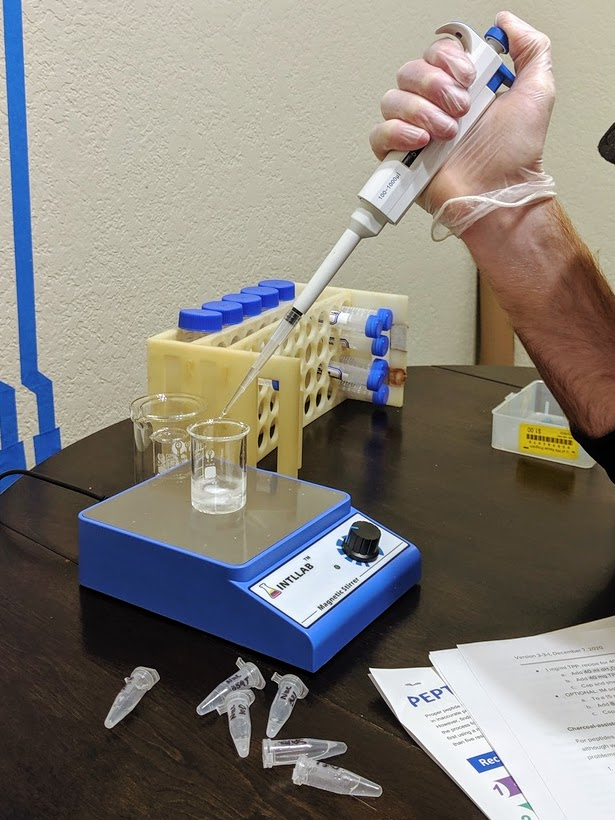

The actual preparation process involves three main high-level steps:

- Prepare solutions of each component - basically dissolve everything separately, then stick it in the freezer until it’s needed.

- Circularize two of the peptides. Concretely, this means adding a few grains of activated charcoal to the tube and gently shaking it for three hours. Then, back in the freezer.

- When it’s time for a batch, take everything out of the freezer and mix it together.

Prepping a batch mostly just involves pipetting things into a beaker on a stir plate, sometimes drop-by-drop.

Finally, a dose goes into a microcentrifuge tube. We stick the intake tube of a sprayer into the tube, and inhale.

That’s the process, at a high level. Multiple boosters are strongly recommended, so there’s a few iterations of this, though only the “take stuff out of the freezer and mix it together” step needs to be repeated. See the whitepaper for the full protocol details, as well more information about each of the peptides and what the other ingredients do (summary: chitosan nanoparticles).

The Plan

The key problem is how to check that the vaccine worked. If it were injected, that would be easy: just get a standard COVID antibody test. Inhaling makes it a lot harder to hurt yourself, but also complicates testing.

The whitepaper goes into more detail and half-a-dozen different types of immune response, but the basic issue is that immunity response in the mucus lining (i.e. nose, lung, airway surfaces) can occur independently of response in the bloodstream. Commercial COVID antibody tests generally check a blood draw. In principle one can run a similar antibody test on a mucus sample, but <reasons>, so the commercial tests check blood.

(Side note: in many ways immunity in the mucus lining is better than in the blood, since it blocks infection at the point where it’s introduced. This is an advantage of inhaled vaccines over injected. So why do most commercial vaccines inject? Turns out logistics are a major constraint on commercial vaccine design, and injections are surprisingly easier logistically. One of the major relative advantages of radvac is that it’s intended to be prepared on-site shortly before administration, so it can use techniques which work better but don’t scale as well. That largely balances out the constraints of readily-available materials and simple preparation. As usual, the whitepaper goes into much more detail on this, including several other logistics-related relative advantages - multiple boosters, custom peptides, frequent design updates, etc.)

The whitepaper claims that “over a hundred” researchers have self-administered the vaccine so far, but I have not been able to find any data on test results from any of them. The paper says that inhaled vaccine can induce immunity in the blood, but I don’t have a quantitative feel for how likely that is, other than the usual assumption that more dakka makes it more likely. Meanwhile, I don’t have a convenient way to test for immune response other than the commercial tests.

So, the current plan is to search under the streetlamp. We’ll just use the commercial tests. Both of us got an antibody test before starting the project, and both came back negative.

My current model is:

- If the vaccine induces an immune response in the blood, then it almost certainly induces one in the mucus lining, but the reverse does not hold. So a positive blood antibody test means it definitely works, a negative antibody test is a weak update against.

- There’s some chance that a few doses are more than enough to induce a blood response.

- There’s some chance that more dakka will induce a blood response, even if the first few doses aren’t enough.

So, we’ll do (up to) two more blood tests. The first will be two weeks after our third (weekly) dose; that one is the “optimistic” test, in case three doses is more-than-enough already. That one is optimistic for another reason as well: synthesis/delivery of three of the nine peptides was delayed, so our first three doses will only use six of them. If the optimistic test comes back positive, great, we’re done.

If that test comes back negative, then the next test will be the “more dakka” test. We’ll add the other three peptides, take another few weeks of boosters, maybe adjust frequency and/or dosage - we’ll consider exactly what changes to make if and when the optimistic test comes back negative. Risks are very minimal (again, see the paper), so throwing more dakka at it makes sense.

Consider this a pre-registration. I intend to share my test results here.

Motivations

Why am I doing this?

I imagine, a year or two from now, looking back and grading my COVID response. When I imagine an A+ response, it’s something like “make my own fast tests, and my own vaccine, test that they actually work, and do all that in spring 2020”. We’ve all been complaining about how “we” (i.e. society) should do these things, yet to a large extent they’re things which we can do for ourselves unilaterally. Doing it for ourselves doesn’t capture all the benefits - lots of fun stuff is still closed/cancelled - but it’s enough to go out, socialize, and generally enjoy life without worrying about COVID.

I’ve written a blog post about Benjamin Jesty, the dairy farmer who successfully immunized his wife and kids against smallpox the same year that King Louis XV of France died of the disease. I explicitly use this as an example of what Rationalism should strive to consistently achieve. Yet when a near-perfect real world equivalent came along, on super-easy mode with most of the work already done by somebody else, it still took me until December to notice. The radvac vaccine showed up in my newsfeed back in July, and I apparently failed to double-click. That level of performance is embarrassing, and I doubt that I will grade my COVID response any higher than a D.

So I’m doing this, in part, to condition the mental motions. To build the habit of Doing This Sort Of Thing, so next time I hopefully do better than a D.

Of course, the concrete benefits are nice too. But at this point it’s only ~4 months until I’d get a vaccine anyway, so the price tag is only arguably worthwhile. It’s still a fun project in its own right, and it gets dramatically cheaper with more people (remember, $1000 bought enough supplies for ~500 doses). Concretely, the largest benefits are in risk reduction. If there’s big hiccups in commercial vaccine deployment, this becomes much more worthwhile. If the South Africa strain turns out to evade commercial vaccines, this becomes much more worthwhile - the radvac design is frequently updated based on the latest COVID research, so we hopefully wouldn’t need to wait around for approval of a new commercial vaccine.

Finally, I'm curious whether it will work - or whether we'll be able to tell that it works. It's a data point as to just how often large bills are left sitting on sidewalks just a little ways off the beaten path.

The solution in the paper you link is literally the solution Eliezer described trying, and not working:

(Note that the "little lightbox" in question was very likely one of these, which you may notice have mostly ratings of 10,000 lux rather than the 2,500 cited in the paper. So, significantly brighter, and despite that, didn't work.)

It does sound like you misunderstood, in other words. Knowing that light exposure is an effective treatment for SAD is indeed a known solution; this is why Eliezer tried light boxes to begin with. The point of that excerpt is that this "known solution" did not work for his wife, and the obvious next step of scaling up the amount of light used was not investigated in any of the clinical literature.

This is simply a (slightly) disguised variation of your original argument. Absent strong reasons to expect to see efficiency, you should not expect to see efficiency. The "entire world desperately looking for a way to stop COVID" led to bungled vaccine distribution, delayed production, supply shortages, the list goes on and on. Empirically, we do not observe anything close to efficiency in this market, and this should be obvious even without the aid of Dentin's list of bullet points (though naturally those bullet points are very helpful).

(Question: did seeing those bullet points cause you to update at all in the direction of this working, or are you sticking with your 1-2% prior? The latter seems fairly indefensible from an epistemic standpoint, I think.)

Not only is the argument above flawed, it's also special pleading with respect to COVID. Here is the analogue of your argument with respect to SAD:

SAD is not an uncommon disorder. In terms of QALYs lost, it's... probably not directly comparable with COVID, but it's at the very least in the same ballpark--certainly to the point where "people want to stop COVID, but they don't care about SAD" is clearly false.

And yet, in point of fact, there are no papers describing the unspeakably obvious intervention of "if your lights don't seem to be working, use more lights", nor are there any companies predicated on this idea. If Eliezer had followed your reasoning to its end conclusion, he might not have bothered testing more light... except that his background assumptions did not imply the (again, fairly indefensible, in my view) heuristic that "if no one else is doing it, the only possible explanation is that it must not work, else people are forgoing free money". And as a result, he did try the intervention, and it worked, and (we can assume) his wife's quality of life was improved significantly as a result.

If there's an argument that (a) applies in full generality to anything other people haven't done before, and (b) if applied, would regularly lead people to forgo testing out their ideas (and not due to any object-level concerns, either, e.g. maybe it's a risky idea to test), then I assert that that argument is bad and harmful, and that you should stop reasoning in this manner.