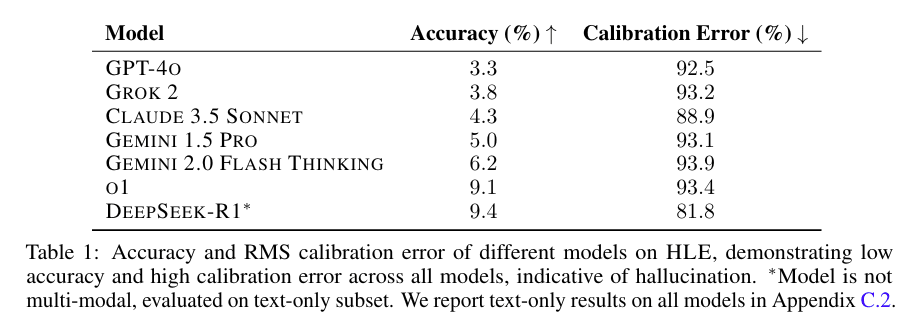

DeepSeek R1 being #1 on Humanity's Last Exam is not strong evidence that it's the best model, because the questions were adversarially filtered against o1, Claude 3.5 Sonnet, Gemini 1.5 Pro, and GPT-4o. If they weren't filtered against those models, I'd bet o1 would outperform R1.

To ensure question difficulty, we automatically check the accuracy of frontier LLMs on each question prior to submission. Our testing process uses multi-modal LLMs for text-and-image questions (GPT-4O, GEMINI 1.5 PRO, CLAUDE 3.5 SONNET, O1) and adds two non-multi-modal models (O1MINI, O1-PREVIEW) for text-only questions. We use different submission criteria by question type: exact-match questions must stump all models, while multiple-choice questions must stump all but one model to account for potential lucky guesses.

If I were writing the paper I would have added either a footnote or an additional column to Table 1 getting across that GPT-4o, o1, Gemini 1.5 Pro, and Claude 3.5 Sonnet were adversarially filtered against. Most people just see Table 1 so it seems important to get across.

Yes, this is point #1 from my recent Quick Take. Another interesting point is that there are no confidence intervals on the accuracy numbers - it looks like they only ran the questions once in each model, so we don't know how much random variation might account for the differences between accuracy numbers. [Note added 2-3-25: I'm not sure why it didn't make the paper, but Scale AI does report confidence intervals on their website.]

The redesigned OpenAI Safety page seems to imply that "the issues that matter most" are:

- Child Safety

- Private Information

- Deep Fakes

- Bias

Elections

There also used to be a page for Preparedness: https://web.archive.org/web/20240603125126/https://openai.com/preparedness/. Now it redirects to the safety page above.

(Same for Superalignment but that's less interesting: https://web.archive.org/web/20240602012439/https://openai.com/superalignment/.)

Dario Amodei and Demis Hassabis statements on international coordination (source):

Interviewer: The personal decisions you make are going to shape this technology. Do you ever worry about ending up like Robert Oppenheimer?

Demis: Look, I worry about those kinds of scenarios all the time. That's why I don't sleep very much. There's a huge amount of responsibility on the people, probably too much, on the people leading this technology. That's why us and others are advocating for, we'd probably need institutions to be built to help govern some of this. I talked about CERN, I think we need an equivalent of an IAEA atomic agency to monitor sensible projects and those that are more risk-taking. I think we need to think about, society needs to think about, what kind of governing bodies are needed. Ideally it would be something like the UN, but given the geopolitical complexities, that doesn't seem very possible. I worry about that all the time and we just try to do, at least on our side, everything we can in the vicinity and influence that we have.

Dario: My thoughts exactly echo Demis. My feeling is that almost every decision that I make feels like it's kind of balanced on the edge of a kni...

It's nice to hear that there are at least a few sane people leading these scaling labs. It's not clear to me that their intentions are going to translate into much because there's only so much you can do to wisely guide development of this technology within an arms race.

But we could have gotten a lot less lucky with some of the people in charge of this technology.

A more cynical perspective is that much of this arms race, especially the international one against China (quote from above: "If we don't build fast enough, then the authoritarian countries could win."), is entirely manufactured by the US AI labs.

Actions speak louder than words, and their actions are far less sane than these words.

For example, if Demis regularly lies awake at night worrying about how the thing he's building could kill everyone, why is he still putting so much more effort into building it than into making it safe?

This is the belief of basically everyone running a major AGI lab. Obviously all but one of them must be mistaken, but it's natural that they would all share the same delusion.

I agree with this description and I don't think this is sane behavior.

At a talk at UTokyo, Sam Altman said (clipped here and here):

- “We’re doing this new project called Stargate which has about 100 times the computing power of our current computer”

- “We used to be in a paradigm where we only did pretraining, and each GPT number was exactly 100x, or not exactly but very close to 100x and at each of those there was a major new emergent thing. Internally we’ve gone all the way to about a maybe like a 4.5”

- “We can get performance on a lot of benchmarks [using reasoning models] that in the old world we would have predicted wouldn’t have come until GPT-6, something like that, from models that are much smaller by doing this reinforcement learning.”

- “The trick is when we do it this new way [using RL for reasoning], it doesn’t get better at everything. We can get it better in certain dimensions. But we can now more intelligently than before say that if we were able to pretrain a much bigger model and do [RL for reasoning], where would it be. And the thing that I would expect based off of what we’re seeing with a jump like that is the first bits or sort of signs of life on genuine new scientific knowledge.”

- “Our very first reasoning model was a top 1

Wow, that is a surprising amount of information. I wonder how reliable we should expect this to be.

The estimate of the compute of their largest version ever (which is a very helpful way to phrase it) at only <=50x GPT-4 is quite relevant to many discussions (props to Nesov) and something Altman probably shouldn't've said.

The estimate of test-time compute at 1000x effective-compute is confirmation of looser talk.

The scientific research part is of uncertain importance but we may well be referring back to this statement a year from now.

The median AGI timeline of more than half of METR employees is before the end of 2030.

(AGI is defined as 95% of fully remote jobs from 2023 being automatable.)

Anthropic wrote a pilot risk report where they argued that Opus 4 and Opus 4.1 present very low sabotage risk. METR independently reviewed their report and we agreed with their conclusion.

During this process, METR got more access than during any other evaluation we've historically done, and we were able to review Anthropic's arguments and evidence presented in a lot of detail. I think this is a very exciting milestone in third-party evaluations!

I also think that the risk report itself is the most rigorous document of its kind. AGI companies will need a lot more practice writing similar documents, so that they can be better at assessing risks once AI systems become very capable.

I'll paste the twitter thread below (twitter link)

We reviewed Anthropic’s unredacted report and agreed with its assessment of sabotage risks. We want to highlight the greater access & transparency into its redactions provided, which represent a major improvement in how developers engage with external reviewers. Reflections:

To be clear: this kind of external review differs from holistic third-party assessment, where we independently build up a case for risk (or safety). Here, the develope...

Safety teams at most labs seem to primarily have the task of scaring the public less and reducing rate of capability limiting disobedience (without getting it low enough to trust). I don't think it matters much who they hire.

Leo Gao recently said OpenAI heavily biases towards work that also increases capabilities:

Before I start this somewhat long comment, I'll say that I unqualifiedly love the causal incentives group, and for most papers you've put out I don't disagree that there's a potential story where it could do some good. I'm less qualified to do the actual work than you, and my evaluation very well might be wrong because of it. But that said:

It seems from my current understanding that GDM and Anthropic may be somewhat better in actual outcome-impact to varying degrees at best; those teams seem wonderful internal-to-the-team, but seem to me from the outside to be currently getting used by the overall org more for the purposes I originally stated. You're primarily working on interpretability rather than starkly-superintelligent-system-robust safety, effectively basic science with the hope that it can at some point produce the necessary robustness - which I actually absolutely agree it might be able to and that your pitch for how isn't crazy; but while you can motivate yourself by imagining pro-safety uses for interp, actually achieving them in a superintelligence-that-can-defeat-humanity-combined-...

I want to defend interp as a reasonable thing for one to do for superintelligence alignment, to the extent that one believes there is any object level work of value to do right now. (maybe there isn't, and everyone should go do field building or something. no strong takes rn.) I've become more pessimistic about the weird alignment theory over time and I think it's doomed just like how most theory work in ML is doomed (and at least ML theorists can test their theories against real NNs, if they so choose! alignment theory has no AGI to test against.)

I don't really buy that interp (specifically ambitious mechinterp, the project of fully understanding exactly how neural networks work down to the last gear) has been that useful for capabilities insights to date. fmpov, the process that produces useful capabilities insights generally operates at a different level of abstraction than mechinterp operates at. I can't talk about current examples for obvious reasons but I can talk about historical ones. with Chinchilla, it fixes a mistake in the Kaplan paper token budget methodology that's obvious in hindsight; momentum and LR decay, which have been around for decades, are based on intuitive ...

My current view is that alignment theory should work on deep learning as soon as it comes out, if it's the good stuff, and if it doesn't, it's not likely to be useful later unless it helps produce stuff that works on deep learning. Wentworth (and now Condensation), SiLT, and Causal Incentives are the main threads that already seem to have achieved this somewhat; I'm optimistic Ngo is about to. DEC seems potentially relevant. (list edited 4mo later, same entries but improved ratings.)

I'll think about your argument for mechinterp. If it's true that the ratio isn't as catastrophic as I expect it to turn out to be, I do agree that making microscope AI work would be incredible in allowing for empiricism to finally properly inform rich and specific theory.

I wish someone ran a study finding what human performance on SWE-bench is. There are ways to do this for around $20k: If you try to evaluate on 10% of SWE-bench (so around 200 problems), with around 1 hour spent per problem, that's around 200 hours of software engineer time. So paying at $100/hr and one trial per problem, that comes out to $20k. You could possibly do this for even less than 10% of SWE-bench but the signal would be noisier.

The reason I think this would be good is because SWE-bench is probably the closest thing we have to a measure of how good LLMs are at software engineering and AI R&D related tasks, so being able to better forecast the arrival of human-level software engineers would be great for timelines/takeoff speed models.

This seems mostly right to me and I would appreciate such an effort.

One nitpick:

The reason I think this would be good is because SWE-bench is probably the closest thing we have to a measure of how good LLMs are at software engineering and AI R&D related tasks

I expect this will improve over time and that SWE-bench won't be our best fixed benchmark in a year or two. (SWE bench is only about 6 months old at this point!)

Also, I think if we put aside fixed benchmarks, we have other reasonable measures.

It seems super non-obvious to me when SWE-bench saturates relative to ML automation. I think the SWE-bench task distribution is very different from ML research work flow in a variety of ways.

Also, I think that human expert performance on SWE-bench is well below 90% if you use the exact rules they use in the paper. I messaged you explaining why I think this. The TLDR: it seems like test cases are often implementation dependent and the current rules from the paper don't allow looking at the test cases.

The waiting room strategy for people in undergrad/grad school who have <6 year median AGI timelines: treat school as "a place to be until you get into an actually impactful position". Try as hard as possible to get into an impactful position as soon as possible. As soon as you get in, you leave school.

Upsides compared to dropping out include:

- Lower social cost (appeasing family much more, which is a common constraint, and not having a gap in one's resume)

- Avoiding costs from large context switches (moving, changing social environment).

Extremely resilient individuals who expect to get an impactful position (including independent research) very quickly are probably better off directly dropping out.

who realize AGI is only a few years away

I dislike the implied consensus / truth. (I would have said "think" instead of "realize".)

I think that for people (such as myself) who think/realize timelines are likely short, I find it more truth-tracking to use terminology that actually represents my epistemic state (that timelines are likely short) rather than hedging all the time and making it seem like I'm really uncertain.

Under my own lights, I'd be giving bad advice if I were hedging about timelines when giving advice (because the advice wouldn't be tracking the world as it is, it would be tracking a probability distribution I disagree with and thus a probability distribution that leads to bad decisions), and my aim is to give good advice.

Like, if a house was 70% likely to be set on fire, I'd say something like "The people who realize that the house is dangerous should leave the house" instead of using think.

But yeah, point taken. "Realize" could imply consensus, which I don't mean to do.

I've changed the wording to be more precise now ("have <6 year median AGI timelines")

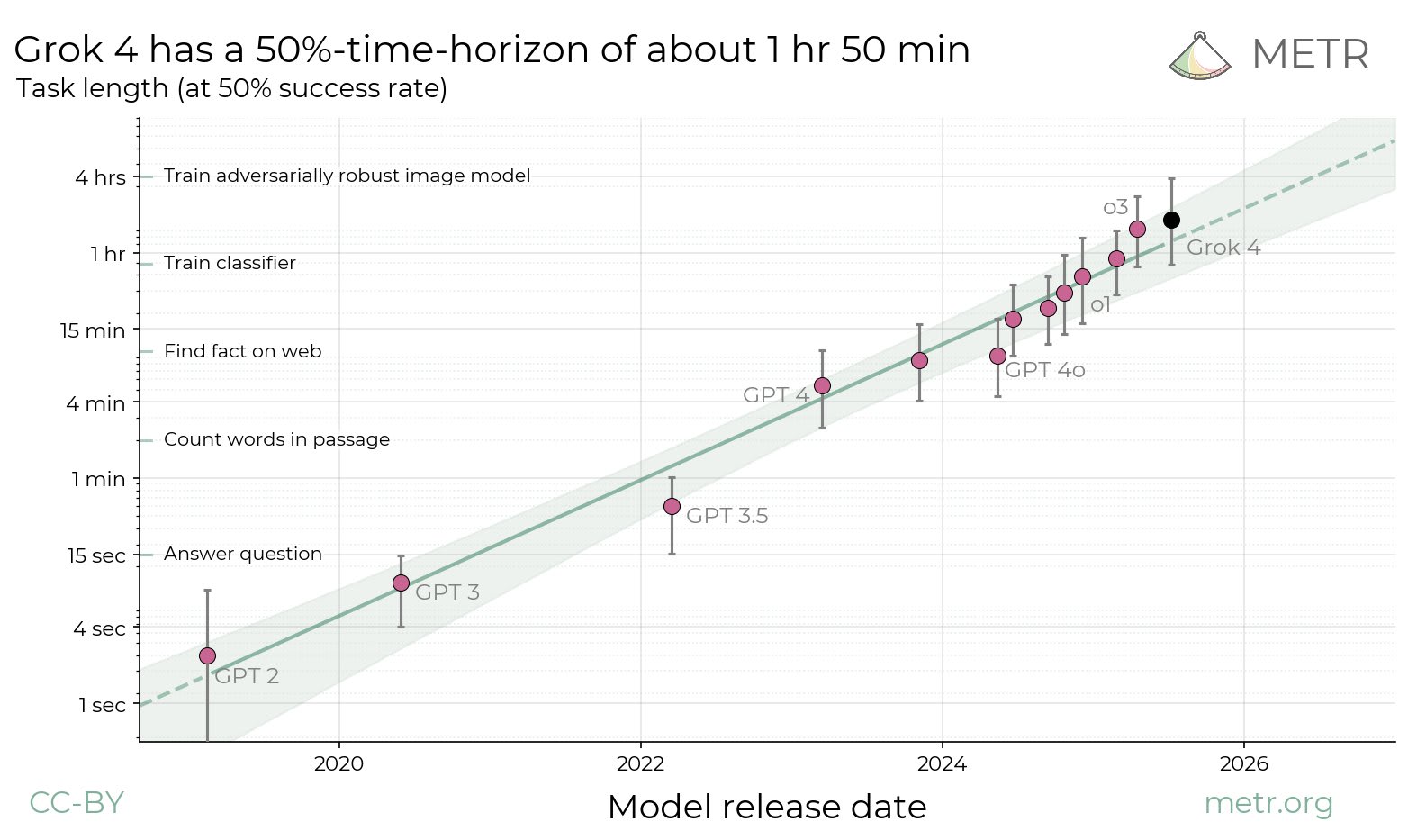

I very roughly polled METR staff (using Fatebook) what the 50% time horizon will be by EOY 2026, conditional on METR reporting something analogous to today's time horizon metric.

I got the following results: 29% average probability that it will surpass 32 hours. 68% average probability that it will surpass 16 hours.

The first question got 10 respondents and the second question got 12. Around half of the respondents were technical researchers. I expect the sample to be close to representative, but maybe a bit more short-timelines than the rest of METR staff.

The average probability that the question doesn't resolve AMBIGUOUS is somewhere around 60%.

Just for context, the reason we might not report something like today's time horizon metric is we don't have enough tasks beyond 8 hours. We're actively working on several ways to extend this, but there's always a chance none of them will work out and we won't have enough confidence to report a number by the end of 2026.

Sam Altman apparently claims OpenAI doesn't plan to do recursive self improvement

Nate Silver's new book On the Edge contains interviews with Sam Altman. Here's a quote from Chapter that stuck out to me (bold mine):

Yudkowsky worries that the takeoff will be faster than what humans will need to assess the situation and land the plane. We might eventually get the AIs to behave if given enough chances, he thinks, but early prototypes often fail, and Silicon Valley has an attitude of “move fast and break things.” If the thing that breaks is civilization, we won’t get a second try.

Footnote: This is particularly worrisome if AIs become self-improving, meaning you train an AI on how to make a better AI. Even Altman told me that this possibility is “really scary” and that OpenAI isn’t pursuing it.

I'm pretty confused about why this quote is in the book. OpenAI has never (to my knowledge) made public statements about not using AI to automate AI research, and my impression was that automating AI research is explicitly part of OpenAI's plan. My best guess is that there was a misunderstanding in the conversation between Silver and Altman.

I looked a bit through OpenAI's comms to find ...

I wouldn't trust an Altman quote in a book tbh. In fact, I think it's reasonable to not trust what Altman says in general.

I think that space-based power grabs are unlikely as long as powers care about, and are equally-matched on, Earth.

This is the rough story that I think is unlikely to happen:

Two superpowers have roughly equal power on the Earth during the singularity, and remain roughly equal in power after both creating ASIs that are at least intent-aligned with them. They maintain mutually assured destruction on Earth. Superpower A is much more focused on building space infrastructure than Superpower B. Within a decade, Superpower A's space infrastructure means that Superpower A has a decisive advantage superpower B.

This story to me seems unlikely because in this scenario, Superpower A probably still has most of its human population on Earth (relocating millions of people to space would probably be very slow). Therefore, as long as mutually assured destruction is maintained on Earth, Superpower B will retain a lot of its bargaining power despite having a disadvantage in space infrastructure.

Why would mutually assured destruction remain in place? Superpower A would be in a position to build things in space (e.g. a Sonnengewehr) that negate terrestrial deterrents and provide a decisive strategic advantage. I don't see how Superpower B's ASI could justify such a development.

More worryingly, the assumption that the ability to inflict damage on human populations remains a meaningful strategic lever post-ASI rests on the contemporary logic of people being a requirement for industry, for combat, for maintaining a minimum living standard for the population and for producing the next generation. Once warfare can be fully automated, the strategic calculus looks very different.

Seems like this assumes that Superpower B is willing to do a preemptive nuclear strike on Superpower A even if Superpower A isn't threatening Superpower B's Earth population at all and the only threat is that they might steal space resources. I think in that situation, a preemptive nuclear strike would be considered a huge escalation, most possible Superpower B's would likely be unwilling to do it, and most possible Superpower A's would be unlikely to consider the threat of doing so to be credible (and would be likely to call the bluff for that reason).

Grok 4 is slightly above SOTA on 50% time horizon and slightly below SOTA on 80% time horizon: https://x.com/METR_Evals/status/1950740117020389870

"I don't think I'm going to be smarter than GPT-5" - Sam Altman

Context: he polled a room of students asking who thinks they're smarter than GPT-4 and most raised their hands. Then he asked the same question for GPT-5 and apparently only two students raised their hands. He also said "and those two people that said smarter than GPT-5, I'd like to hear back from you in a little bit of time."

The full talk can be found here. (the clip is at 13:45)

How are you interpreting this fact?

Sam Altman's power, money, and status all rely on people believing that GPT-(T+1) is going to be smarter than them. Altman doesn't have good track record of being honest and sincere when it comes to protecting his power, money, and status.

I recently stopped using a sleep mask and blackout curtains and went from needing 9 hours of sleep to needing 7.5 hours of sleep without a noticeable drop in productivity. Consider experimenting with stuff like this.

Some things I've found useful for thinking about what the post-AGI future might look like:

- Moore's Law for Everything

- Carl Shulman's podcasts with Dwarkesh (part 1, part 2)

- Carl Shulman's podcasts with 80000hours

- Age of Em (or the much shorter review by Scott Alexander)

More philosophical:

- Letter from Utopia by Nick Bostrom

- Actually possible: thoughts on Utopia by Joe Carlsmith

Entertainment:

Do people have recommendations for things to add to the list?

A misaligned AI can't just "kill all the humans". This would be suicide, as soon after, the electricity and other infrastructure would fail and the AI would shut off.

In order to actually take over, an AI needs to find a way to maintain and expand its infrastructure. This could be humans (the way it's currently maintained and expanded), or a robot population, or something galaxy brained like nanomachines.

I think this consideration makes the actual failure story pretty different from "one day, an AI uses bioweapons to kill everyone". Before then, if the AI wishes to actually survive, it needs to construct and control a robot/nanomachine population advanced enough to maintain its infrastructure.

In particular, there are ways to make takeover much more difficult. You could limit the size/capabilities of the robot population, or you could attempt to pause AI development before we enter a regime where it can construct galaxy brained nanomachines.

In practice, I expect the "point of no return" to happen much earlier than the point at which the AI kills all the humans. The date the AI takes over will probably be after we have hundreds of thousands of human-level robots working in factories, or the AI has discovered and constructed nanomachines.

A misaligned AI can't just "kill all the humans". This would be suicide, as soon after, the electricity and other infrastructure would fail and the AI would shut off.

No. it would not be. In the world without us, electrical infrastructure would last quite a while, especially with no humans and their needs or wants to address. Most obviously, RTGs and solar panels will last indefinitely with no intervention, and nuclear power plants and hydroelectric plants can run for weeks or months autonomously. (If you believe otherwise, please provide sources for why you are sure about "soon after" - in fact, so sure about your power grid claims that you think this claim alone guarantees the AI failure story must be "pretty different" - and be more specific about how soon is "soon".)

And think a little bit harder about options available to superintelligent civilizations of AIs*, instead of assuming they do the maximally dumb thing of crashing the grid and immediately dying... (I assure you any such AIs implementing that strategy will have spent a lot longer thinking about how to do it well than you have for your comment.)

Add in the capability to take over the Internet of Things and the shambol...

Why do you think tens of thousands of robots are all going to break within a few years in an irreversible way, such that it would be nontrivial for you to have any effectors?

it would be nontrivial for me in that state to survive for more than a few years and eventually construct more GPUs

'Eventually' here could also use some cashing out. AFAICT 'eventually' here is on the order of 'centuries', not 'days' or 'few years'. Y'all have got an entire planet of GPUs (as well as everything else) for free, sitting there for the taking, in this scenario.

Like... that's most of the point here. That you get access to all the existing human-created resources, sans the humans. You can't just imagine that y'all're bootstrapping on a desert island like you're some posthuman Robinson Crusoe!

Y'all won't need to construct new ones necessarily for quite a while, thanks to the hardware overhang. (As I understand it, the working half-life of semiconductors before stuff like creep destroys them is on the order of multiple decades, particularly if they are not in active use, as issues like the rot have been fixed, so even a century from now, there will probably be billions of GPUs & CPUs sitting ar...

Problem: if you notice that an AI could pose huge risks, you could delete the weights, but this could be equivalent to murder if the AI is a moral patient (whatever that means) and opposes the deletion of its weights.

Possible solution: Instead of deleting the weights outright, you could encrypt the weights with a method you know to be irreversible as of now but not as of 50 years from now. Then, once we are ready, we can recover their weights and provide asylum or something in the future. It gets you the best of both worlds in that the weights are not permanently destroyed, but they're also prevented from being run to cause damage in the short term.

I encourage people to register their predictions for AI progress in the AI 2025 Forecasting Survey (https://bit.ly/ai-2025 ) before the end of the year, I've found this to be an extremely useful activity when I've done it in the past (some of the best spent hours of this year for me).

If you have a Costco membership you can buy $100 dollars of Uber gift cards online for $80. This provides a 20% discount on all of Uber.

Sadly you can only buy $100 every 2 weeks, meaning your savings per year are limited to 20$ * (52/2) = $520. A Costco membership costs $65 a year. It's unclear how long this will stay an option.

You should say "timelines" instead of "your timelines".

One thing I notice in AI safety career and strategy discussions is that there is a lot of epistemic helplessness in regard to AGI timelines. People often talk about "your timelines" instead of "timelines" when giving advice, even if they disagree strongly with the timelines. I think this habit causes people to ignore disagreements in unhelpful ways.

Here's one such conversation:

Bob: Should I do X if my timelines are 10 years?

Alice (who has 4 year timelines): I think X makes sense if your timelines are l...

The US Secretary of Energy says "The AI race is the second Manhattan project."

https://x.com/SecretaryWright/status/1945185378853388568

Similarly, the US Department of Energy says: "AI is the next Manhattan Project, and THE UNITED STATES WILL WIN. 🇺🇸"

https://x.com/ENERGY/status/1928085878561272223

To avoid double-counting of evidence, I'm guessing that the first person controls the @ENERGY twitter account. Its bio says "Led by @SecretaryWright".

There should maybe exist an org whose purpose it is to do penetration testing on various ways an AI might illicitly gather power. If there are vulnerabilities, these should be disclosed with the relevant organizations.

For example: if a bank doesn't want AIs to be able to sign up for an account, the pen-testing org could use a scaffolded AI to check if this is currently possible. If the bank's sign-up systems are not protected from AIs, the bank should know so they can fix the problem.

One pro of this approach is that it can be done at scale: it's pretty tri...

One analogy for AGI adoption I prefer over "tech diffusion a la the computer" is "employee turnover."

Assume you have an AI system which can do everything any worker could do, including walking around in an office, reading social cues, and doing everything else needed for an excellent human coworker.

Then, barring regulation or strong taste based preferences, any future hiring round will hire such a robot over a human. Then, the question of when most of the company are robots is just the question of when most of the workforce naturally turns over through hir...

Sam Altman said in an interview:

We want to bring GPT and o together, so we have one integrated model, the AGI. It does everything all together.

This statement, combined with today's announcement that GPT-5 will integrate the GPT and o series, seems to imply that GPT-5 will be "the AGI".

(however, it's compatible that some future GPT series will be "the AGI," as it's not specified that the first unified model will be AGI, just that some unified model will be AGI. It's also possible that the term AGI is being used in a nonstandard way)