An idea along these lines was first proposed by Roberts and Sherratt in 1998 and since then have been numerous studies which investigate the idea empirically in both human and non-human animals (c.f. Roberts & Renwick 2003).

Roberts, G., Sherratt, T. Development of cooperative relationships through increasing investment. Nature 394, 175–179 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1038/28160

Roberts, G., & Renwick, J. S. (2003). The development of cooperative relationships: an experiment. Proceedings of the Royal Society, 270, 2279–2283. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?artid=1691507&blobtype=pdf

Further to my original comment, this idea has also been discussed in non-human animals in the context of biological markets (Noe & Hammerstein 1995). In nature, many forms of cooperation can be described in terms of trade, e.g. primate allo-grooming effort can be used as a medium of exchange to obtain not just reciprocal grooming but also can be traded for other goods and services (Barrett et al. 1999).

In artificial markets, counter-party risk can be mitigated through institutions which enforce contracts, but in biological markets this is not possible. Incremental increasing of "bids" has been proposed as one explanation of how large-scale cooperation can be bootstrapped in nature (c.f. Phelps & Russell 2015, Section 4 for a review).

Barrett, L., Henzi, S. P., Weingrill, T., Lycett, J. E., & Hill, R. A. (1999). Market forces predict grooming reciprocity in female baboons. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 266(1420), 665–665. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1999.0687

Noë, R., & Hammerstein, P. (1995). Biological markets. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 10(8), 336–339. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/els/01695347/1995/00000010/00000008/art89123

Phelps, S., & Russell, Y. I. (2015). Economic drivers of biological complexity. Adaptive Behavior, 23(5), 315–326. https://sphelps.net/papers/ecodrivers-20150601-ab-final.pdf

That paper about economic drivers of biological complexity is fascinating! In particular I am amazed I never noticed that lekking is an auction. The paper lends some credence to my intuition that capitalism is actually isomorphic to the natural state. Are you the Phelps that was involved in writing it?

Also: I wonder if you'd be interested in my vague notion that genes trade with one another using mutability as a currency.

I like that offers a clearer theory of what boundaries are than most things I've read on the subject. I often find the idea of boundaries weird not because I don't understand that sometimes people need to put up social defenses of various kinds to feel safe but because I've not seen a very crisp definition of boundaries that didn't produce a type error. Framing in terms of bids for greater connect hits at a lot of what I think folks care about when they talk about setting boundaries, so it makes a lot more sense to me now than my previous understanding, which was more like "I'm going to be emotionally closed here because I can't handle being open" which is still kind of true but mixes in a lot of stuff and so is not a crisp notion.

@Richard_Ngo I notice this has been tagged as "Internal Alignment (Human)", but not "AI". Do you see trust-building in social dilemmas as a human-specific alignment technique, or do you think it might also have applications to AI safety? The reason I ask is that I am currently researching how large-language models behave in social dilemmas and other non-zero-sum games. We started with the repeated Prisoner's Dilemma, but we are also currently researching how LLM-instantiated simulacra behave in the ultimatum game, public goods, donation-game, raise-the-stakes (i.e. a game similar to the idea outlined in your post, and as per Roberts and Sheratt 98) and various other experimental economics protocols. The original motivation for this was AI safety research, but an earlier post on this topic elicited a only a very like-warm response. As an outsider to the field I am still trying to gauge how relevant our research is to the AI-safety community. The arXiv version of our working paper is arXiv:2305.07970. Any feedback greatly appreciated.

Curated. I really liked this very clear discussion of bids and the development of trust. I also thought it had subtle but important points that aren't always mentioned, such as the way that trust built up via fulfilling all bids is fragile.

By “making bids” I mean doing something which invites a response from the other person, where a positive response would bring you closer together.

I would add a caveat, a positive response the bidder perceives to be genuine and sincere, otherwise it's quite possible for the bidder to evaluate a genuine and sincere negative response to be higher then an uncertain positive response.

Strong upvote. I found that almost every sentence was extremely clear and conveyed a transparent mental image of the argument made. Many times I found myself saying to myself "YES!" or "This checks" as I read a new point.

That might involve not working on a day you’ve decided to take off even if something urgent comes up; or deciding that something is too far out of your comfort zone to try now, even if you know that pushing further would help you grow in the long term

I will add that, for many routine activities or personal dilemmas with short- and long-term intentions pulling you in opposite directions (e.g. exercising, eating a chocolate bar), the boundaries you set internally should be explicit and unambiguous, and ideally be defined before being faced by the choice.

This is to avoid rationalising momentary preferences (I am lazy right now + it's a bit cloudy -> "the weather is bad, it might rain, I won't enjoy running as much as if it was sunny, so I won't go for a run") that run counter to your long-term goals, where the result of defecting a single time would be unnoticeable for the long run. In this cases it can be helpful to imagine your current self in a bargaining game with your future selves, in a sort of prisoner's dilema. If your current now defects, your future selves will be more prone to defecting as well. If you coordinate and resist tempation now, future resistance will be more likely. In other words, establishing a Schelling fence.

At the same time, this Schelling fence shouldn't be too restrictive nor be merciless towards any possible circumstance, because then this would make you more demotivated and even less inclined to stick to it. One should probably experiment with what works for him/her in order to find a compromise between a bucket broad and general enough for 70-90% of scenarios to fall into, while being merciful towards some needed exceptions.

In this cases it can be helpful to imagine your current self in a bargaining game with your future selves, in a sort of prisoner's dilema. If your current now defects, your future selves will be more prone to defecting as well. If you coordinate and resist tempation now, future resistance will be more likely. In other words, establishing a Schelling fence.

This is an interesting way of looking at it. To elaborate a bit, one day of working toward a long-term goal is essentially useless, so you will only do it if you believe that your future selves will as well. This is some of where the old "You need to believe in yourself to do it!" advice comes from. But there can be good reasons not to believe in yourself as well.

In the context of the iterated Prisoner's Dilemma, it's been investigated what the frequency of random errors (the decision to cooperate or defect being replaced with a random one in x% of instances) can go up to before cooperation breaks down. (I'll try to find a citation for this later.) This seems similar, but not literally equivalent, to a question we might ask here: What frequency of random motivational lapses can be tolerated before the desire to work towards the goal at all breaks down?

Naturally, the goals that require the most trust are ones that see no benefit until the end, because they require you to trust that your future selves won't permanently give up on the goal anywhere between now and the end to be worth working towards at all. But most long term goals aren't really like this. They could be seen to fall on a spectrum between providing no benefit until a certain point and linear benefit the more they are worked towards with the "goal" point being arbitrary. (This is analogous to the concept of a learning curve.) Actions towards a goal may also provide an immediate benefit as well as progress toward the goal, which reduces the need to trust your future selves.

If you don't trust your future selves very much, you can seek out "half-measure" actions that sacrifice some efficiency toward the goal for immediate benefits, but still contribute some progress toward the goal. You can to some extent set where they are along this spectrum, but you are also limited by the types of actions available to you.

The LessWrong Review runs every year to select the posts that have most stood the test of time. This post is not yet eligible for review, but will be at the end of 2024. The top fifty or so posts are featured prominently on the site throughout the year.

Hopefully, the review is better than karma at judging enduring value. If we have accurate prediction markets on the review results, maybe we can have better incentives on LessWrong today. Will this post make the top fifty?

In my previous post, I talked through the process of identifying the fears underlying internal conflicts. In some cases, just listening to and understanding those scared parts is enough to make them feel better—just as, when venting to friends or partners, we often primarily want to be heard rather than helped. In other cases, though, parts may have more persistent worries—in particular, about being coerced by other parts. The opposite of coercion is trust: letting another agent do as they wish, without trying to control their behavior, because you believe that they’ll take your interests into account. How can we build trust between different parts of ourselves?

I’ll start by talking about how to cultivate trust between different people, since we already have many intuitions about how that works; and then apply those ideas to the task of cultivating self-trust. Although it's tempting to think of trust in terms of grand gestures and big sacrifices, it typically requires many small interactions over time to build trust in a way that all the different parts of both people are comfortable with. I’ll focus on two types of interactions: making bids and setting boundaries.

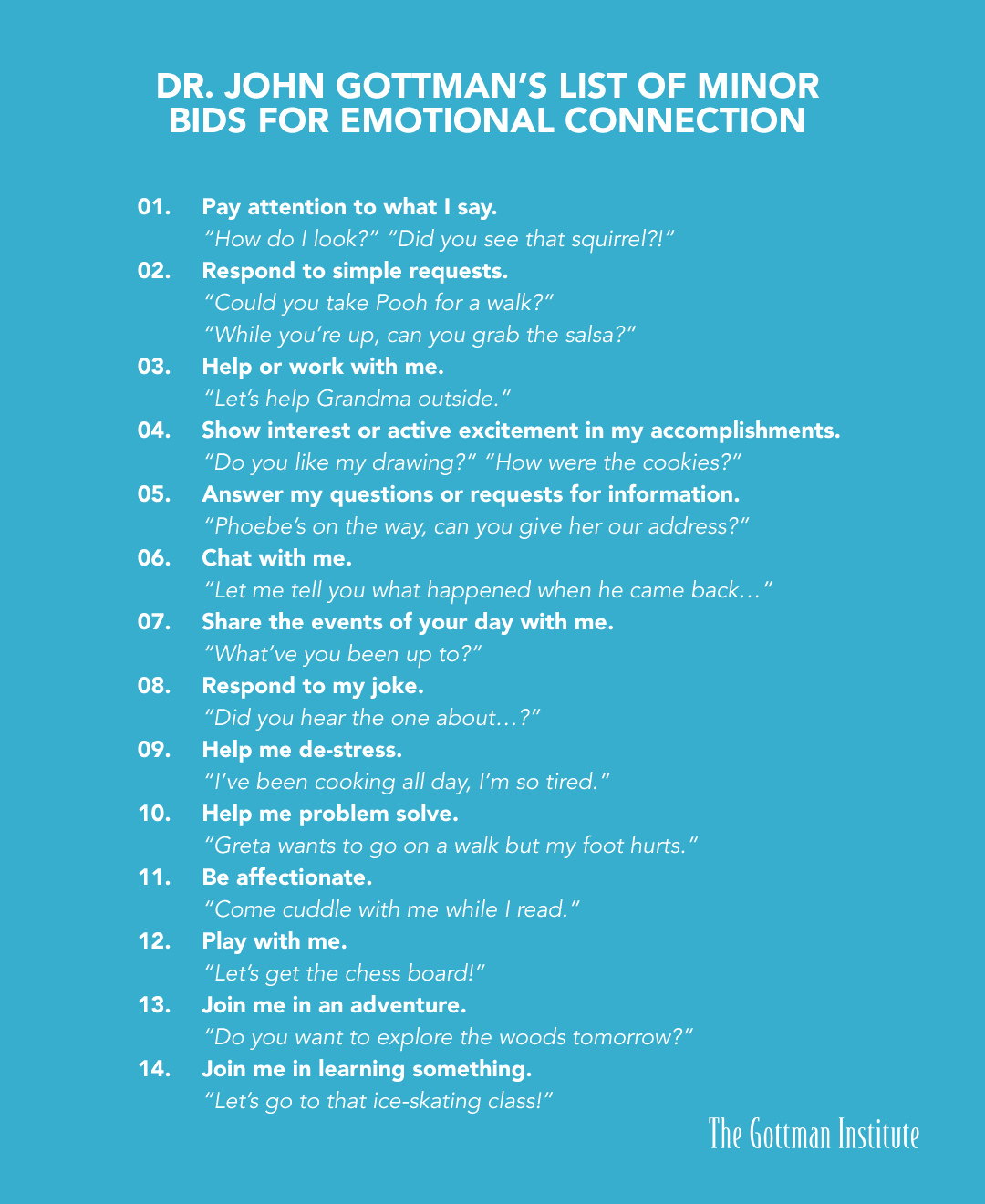

By “making bids” I mean doing something which invites a response from the other person, where a positive response would bring you closer together. You can read about them in the work of John Gottman, who gives many examples:

Sometimes bids are explicit, like asking somebody out on a date. But far more often they’re implicit—perhaps greeting someone more warmly than usual, or dropping a hint that your birthday is coming up. One reason that people make their bids subtle and ambiguous is because they’re scared of the feeling of a bid being rejected, and subtle bids can be rejected gently by pretending to not notice them. Another is that many outcomes (e.g. being given a birthday present) feel more meaningful when you haven't asked for them directly. Some more examples of bids that are optimized for ambiguity:

Of course, the downside of making ambiguous bids is that the other person often doesn't notice that you're making a bid for connection—or, worse, interprets the bid itself as a rejection. As in the example above, a complaint about messiness is a kind of bid for care, but one which often creates anger rather than connection. So overcoming the fear of expressing bids directly is a crucial skill. Even when making a bid explicit renders the response less meaningful (like directly asking your parents whether they're proud of you), you can often get the best of both worlds by making a meta-level bid (e.g. asking your parents to talk about how they express their emotions) which then provides a safer way to bring up your underlying need (e.g. for them to be more positive, or at least less negative, in how they talk to you).

There's a third major reason we make ambiguous bids, though. The more direct our bids, the more pressure recipients feel to accept them—and it’s scary to think that they might accept but resent us for asking. The best way to avoid that is to be genuinely unafraid of the bid being turned down, in a way that the recipient can read from your voice and demeanor. Of course, you can’t just decide to not be scared—but the more explicit bids you make, the easier it is to learn that rejection isn’t the end of the world. In the meantime, you can give the other person alternative options when making the bid, or tell them explicitly that it’s okay to say no.

Ultimately, however, you can’t take full responsibility for other people’s inability to turn down bids. Many people are conflict-averse and feel strong pressure in response to even indirect bids. When someone says something that could be interpreted as a complaint, listeners often rush to reassure them, contradict them, or try to fix it—even when none of these are actually what the complainer is looking for. The frantic need to manage others’ bids becomes particularly noticeable once you’ve experienced the practice of circling, which can be roughly summarized as having a conversation about your emotions without treating any statements as implicit bids. This can be a very uncomfortable experience at first, but being able to respond to bids in a way that isn’t driven by fear is incredibly valuable, and is the core skill behind the second aspect of building trust: setting boundaries.

Setting boundaries is about not accepting bids which a part of you will resent having accepted, and clearly communicating this to the people making the bids—for example, telling a friend when you don’t have the energy to talk about their problems, even if they seem sad. It’s easy to continue accepting bids even if that builds up a lot of resentment over time, because it’s scary to think that someone might resent us for rejecting them. But in most cases setting boundaries isn’t actually a selfish move, but rather an investment in that relationship—not just because it makes you feel more positively towards the other person, but also because it creates safety for them to make other bids. If you’re capable of setting boundaries, then they no longer need to carefully figure out which bids you’ll accept happily and which you’ll accept begrudgingly, and they’ll likely end up having more bids accepted over the long term.

Trust which is built up via fulfilling all bids is fragile—if a bid is ever rejected, that feels like an unprecedented disaster! Trust which is built up via fulfilling the bids that work, and making clear which ones don’t, is much more robust—especially because saying no to a bid is often a starting point, not an ending point. In most scenarios there are compromise options which you’d both be happy with, which it’s much easier to collaboratively discover after you’ve surfaced your true preferences—and which are often much better for the other person than just accepting their original bid, because now they don’t need to second-guess how you really feel.

All of the above applies internally just as much as externally—and usually more so, because our parts are stuck with each other permanently, and have often built up a lot of resentment or hurt over time. An analogy I like here is the process of taming a wild animal—many parts of us are skittish, and so being careful and gentle with them goes a long way. Since those parts often haven't felt empowered to set boundaries before, it might take some costly signals of self-loyalty to convince them that their preferences will actually be respected. That might involve not working on a day you’ve decided to take off even if something urgent comes up; or deciding that a new experience is too far out of your comfort zone to try now, even if you know that pushing further would help you grow in the long term. But enforcing boundaries a few times typically enables you to do more of the thing you originally refused: most things are much less scary when you trust that you’ll let yourself stop if you really want to.

"You must be very patient," replied the fox. "First you will sit down at a little distance from me--like that--in the grass. I shall look at you out of the corner of my eye, and you will say nothing. Words are the source of misunderstandings. But you will sit a little closer to me, every day . . ."