This looks cool and I want to read it in detail, but I'd like to push back a bit against an implicit take that I thought was present here: namely, that GDP takes into account major technological breakthroughs. Let me just quote some text from this article: What Do GDP Growth Curves Really Mean?

More generally: when the price of a good falls a lot, that good is downweighted (proportional to its price drop) in real GDP calculations at end-of-period prices.

… and the way we calculate real GDP in practice is to use prices from a relatively recent year. We even move the reference year forward from time to time, so that it’s always near the end of the period when looking at long-term growth.

Real GDP Mainly Measures The Goods Which Are Revolutionized Least

Now let’s go back to our puzzle about growth since 1960, and electronics in particular.

The cost of a transistor has dropped by a stupidly huge amount since 1960 - I don’t have the data on hand, but let’s be conservative and call it a factor of 10^12 (i.e. a trillion). If we measure in 1960 prices, the transistors on a single modern chip would be worth billions. But instead we measure using recent prices, so the transistors on a single modern chip are worth… about as much as a single modern chip currently costs. And all the world’s transistors in 1960 were worth basically-zero.

1960 real GDP (and 1970 real GDP, and 1980 real GDP, etc) calculated at recent prices is dominated by the things which are expensive today - like real estate, for instance. Things which are cheap today are ignored in hindsight, even if they were a very big deal at the time.

In other words: real GDP growth mostly tracks production of goods which aren’t revolutionized. Goods whose prices drop dramatically are downweighted to near-zero, in hindsight.

When we see slow, mostly-steady real GDP growth curves, that mostly tells us about the slow and steady increase in production of things which haven’t been revolutionized. It tells us approximately-nothing about the huge revolutions in e.g. electronics.

Yeah I actually do cite that piece in the appendix 'GDP as a proxy for welfare' where I list more literature like this. So yeah, it's not a perfect measure but it's the one we have and 'all models are wrong but some are useful' and GDP is quite a powerful predictor of all kinds of outcomes:

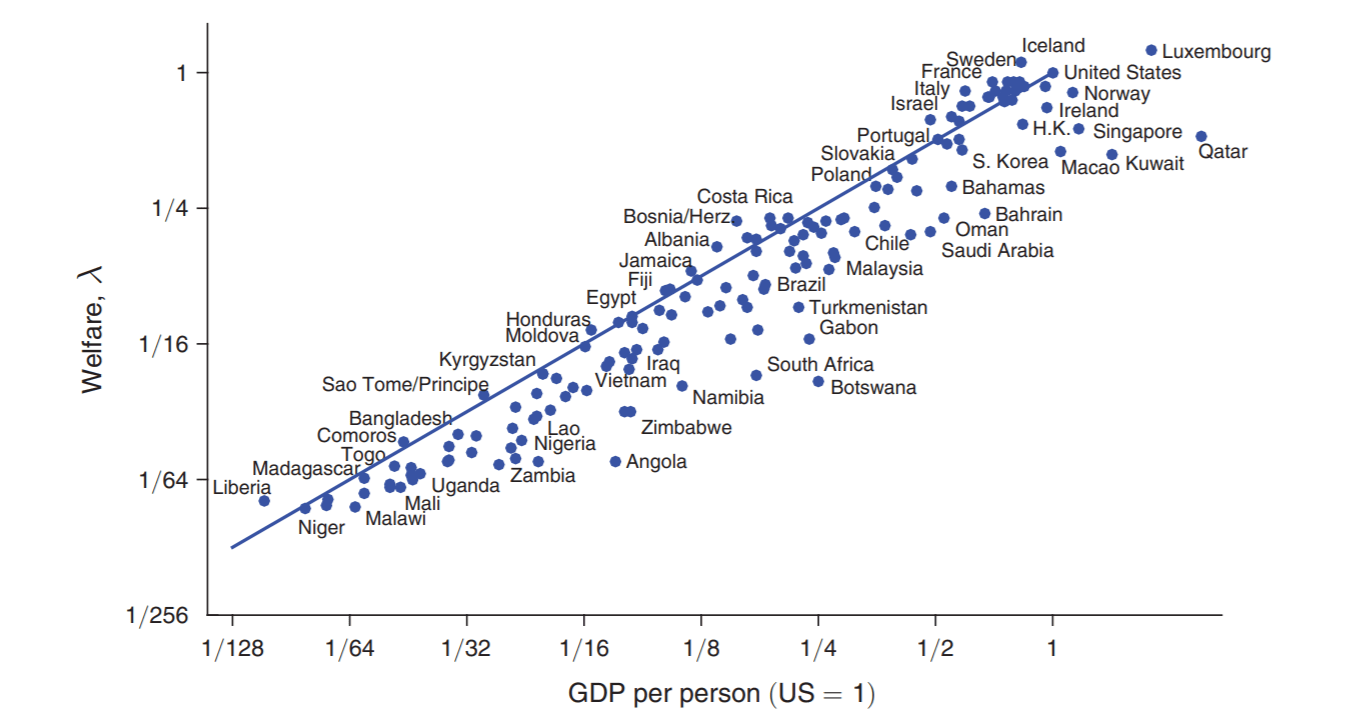

In a 2016 paper, Jones and Klenow used measures of consumption, leisure, inequality, and mortality, to create a consumption-equivalent welfare measure that allows comparisons across time for a given country, as well as across countries.[6]

This measure of human welfare suggests that the true level of welfare of some countries differs markedly from the level that might be suggested by their GDP per capita. For example, France’s GDP per capita is around 60% of US GDP per capita.[7] However, France has lower inequality, lower mortality, and more leisure time than the US. Thus, on the Jones and Klenow measure of welfare, France’s welfare per person is 92% of US welfare per person.[8]

Although GDP per capita is distinct from this expanded welfare metric, the correlation between GDP per capita and this expanded welfare metric is very strong at 0.96, though there is substantial variation across countries, and welfare is more dispersed (standard deviation of 1.51 in logs) than is income (standard deviation of 1.27 in logs).[9]

GDP per capita is also very strongly correlated with the Human Development Index, another expanded welfare metric.[10] If measures such as these are accurate, this shows that income per head explains most of the observed cross-national variation in welfare. It is a distinct question whether economic growth explains most of the observed variation across individuals in welfare. It is, however, clear that it explains a substantial fraction of the variation across individuals.

Although GDP per capita is distinct from this expanded welfare metric, the correlation between GDP per capita and this expanded welfare metric is very strong at 0.96, though there is substantial variation across countries, and welfare is more dispersed (standard deviation of 1.51 in logs) than is income (standard deviation of 1.27 in logs).[9]

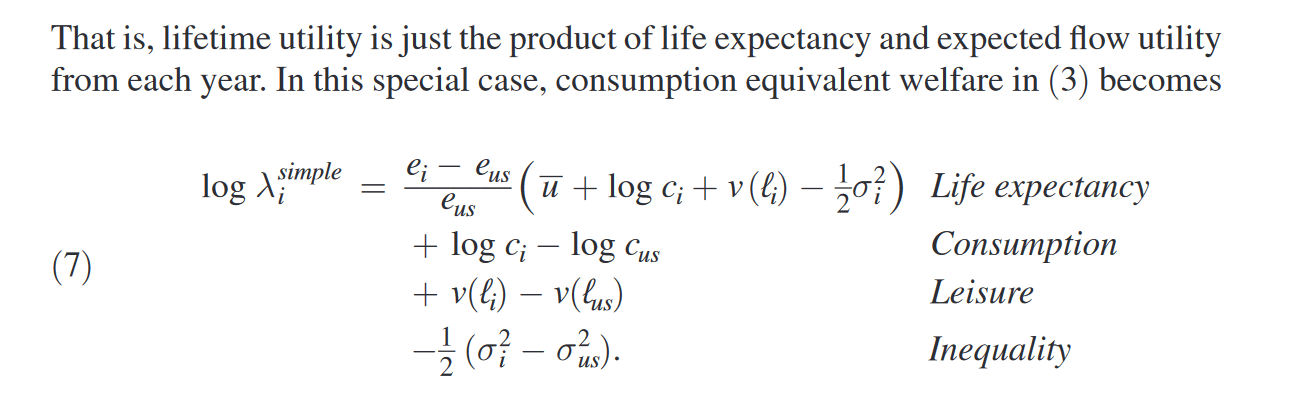

I checked the paper and it looks like they're comparing welfare by "how much more would person X from the US have to consume to move to another country i?" Which results in equations like this:

which says what the factor , should be in terms of differences in life expectancy, consumption, lessure and inequality. So I suppose it isn't suprising that it's quite correlated with GDP, given the individual correlations at play here, but I am suprised that it is so strongly correlated since I'd expect e.g. life expectancy vs gdp to correlate at maybe 0.8[1]. Which is a fair bit weaker than a 0.96 correlation!

Good point. I grabbed the dataset of gdp per capita vs life expectancy for almost all nations from OurWorldInData, log transformed GDP per capita and got a correlation of 0.85.

I think there's a good chance the degree to which the world of 2050 looks different to the average person might have very little to do with GDP.

On the one hand, a large chunk of the GDP growth I expect will come from changes in how we produce, distribute, and use energy and chemicals and water and food and steel and concrete etc. But for most people what will mostly feel the same is that their home is warm in winter and cool in summer, and they can get from place to place reasonably easily, and they have machines that do their basic household chores.

On the other hand, something like self-driving cars, or augmented or virtual reality, or 3D printed organs, could be hugely tranaformative for society without necessarily impacting GDP growth much at all.

Survival vs self-expression: Survival values prioritize security over liberty. Those with survival values tend to be more homophobic, uninterested in political action, distrustful of outsiders, and less happy. As people transition from industrial to knowledge societies, their sense of agency increases and they move towards self-expression values.

To me, the empiric status of that claim feels quite unclear. Is that your personal opinion? Is it a general pattern for which there's existing data?

Yes, good catch, this is based on research from the World Value Survey - I've added a citation.

Abstract

Here, I present GDP (per capita) forecasts of major economies until 2050. Since GDP per capita is the best generalized predictor of many important variables, such as welfare, GDP forecasts can give us a more concrete picture of what the world might look like in just 27 years. The key claim here is: even if AI does not cause transformative growth, our business-as-usual near-future is still surprisingly different from today.

Latest Draft as PDF

Results

In recent history, we've seen unprecedented economic growth and rises in living standards.

Consider this graph:[1]

How will living standards improve as GDP per capita (GDP/cap) rises? Here, I show data that projects GDP/cap until 2050. Forecasting GDP per capita is a crucial undertaking as it strongly correlates with welfare indicators like consumption, leisure, inequality, and mortality. These forecasts make the future more concrete and give us a better sense of what the world will look like soon. Abstract thoughts about utopia generate little emotional energy; I find these forecasts more plastic and informative, because GDP/cap is highly predictive of welfare.[2] GDP/cap's generalized predictive power helps us paint a more vivid picture of what the world will look like soon. The business-as-usual near future suggested by the data below could be seen as a soft lower bound on how much the world will change. And yet, this world still seems radically different from today.

Since the figures below are adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP), you can compare the GDP/cap of a poorer country in 2050 with the GDP/cap of a richer country in 2020. For instance, between now and 2050, China's GDP/cap will go from $19k to $43k, which is similar to France's today. And so, by 2050, 1.3B Chinese people might enjoy a lifestyle not dissimilar to that of a typical French person today.

These GDP/cap are ~3x[3] higher than the median (i.e. typical) income, due to income inequality. Instead of downward adjusting them in our head we can also read them as an approximation of the typical combined consumption three person household.[4] And so, we can still look at these figures and imagine the median household income in Japan today and in China in 2050 to be ~$40k.

2020

2024

2030

2040

2050

Pop.

GDP

GDP/ cap

GDP/ cap

Pop.

GDP/ cap

GDP

Pop.

GDP/ cap

GDP

Pop.

GDP/ cap

GDP

US

334M

$20T

$60K

$68K

356M

$66K

$23T

374M

$76K

$28T

389M

$88K

$34T

Netherlands

17M

$1T

$54K

$59K

18M

$61K

$1T

18M

$71K

$1T

18M

$85K

$1T

S. Arabia

34M

$2T

$55K

$56K

39M

$70K

$3T

43M

$86K

$4T

46M

$102K

$5T

Germany

80M

$4T

$52K

$54K

79M

$59K

$5T

77M

$69K

$5T

75M

$82K

$6T

Australia

26M

$1T

$52K

$53K

28M

$58K

$2T

31M

$67K

$2T

33M

$77K

$3T

S. Korea

51M

$2T

$42K

$47K

53M

$50K

$3T

52M

$59K

$3T

51M

$70K

$4T

Canada

38M

$2T

$48K

$48K

40M

$53K

$2T

42M

$61K

$3T

44M

$70K

$3T

UK

67M

$3T

$45K

$47K

70M

$52K

$4T

73M

$61K

$4T

75M

$71K

$5T

France

66M

$3T

$44K

$48K

68M

$50K

$3T

70M

$56K

$4T

71M

$66K

$5T

Japan

125M

$5T

$40K

$43K

120M

$47K

$6T

114M

$54K

$6T

107M

$63K

$7T

Poland

38M

$1T

$31K

$39K

37M

$40K

$2T

35M

$53K

$2T

33M

$63K

$2T

Spain

46M

$2T

$39K

$42K

46M

$47K

$2T

46M

$53K

$2T

45M

$61K

$3T

Malaysia

32M

$1T

$32K

$31K

36M

$42K

$2T

39M

$54K

$2T

41M

$69K

$3T

Italy

60M

$2T

$39K

$45K

59M

$43K

$3T

58M

$48K

$3T

57M

$55K

$3T

Turkey

82M

$2T

$26K

$35K

88M

$34K

$3T

93M

$43K

$4T

96M

$54K

$5T

Russia

143M

$4T

$28K

$31K

139M

$34K

$5T

133M

$45K

$6T

129M

$55K

$7T

China

1403M

$27T

$19K

$20K

1416M

$27K

$38T

1395M

$34K

$47T

1348M

$43K

$58T

Thailand

69M

$1T

$19K

$19K

68M

$25K

$2T

66M

$34K

$2T

62M

$45K

$3T

Argentina

46M

$1T

$22K

$21K

49M

$27K

$1T

53M

$34K

$2T

55M

$43K

$2T

Mexico

135M

$3T

$19K

$21K

148M

$25K

$4T

158M

$32K

$5T

164M

$42K

$7T

Colombia

50M

$1T

$16K

$16K

53M

$21K

$1T

55M

$28K

$2T

55M

$38K

$2T

Iran

83M

$2T

$21K

$17K

89M

$27K

$2T

91M

$35K

$3T

92M

$42K

$4T

Indonesia

272M

$4T

$14K

$13K

295M

$18K

$5T

312M

$25K

$8T

322M

$33K

$11T

Brazil

216M

$3T

$15K

$17K

229M

$19K

$4T

236M

$25K

$6T

238M

$32K

$8T

S. Africa

57M

$1T

$14K

$13K

60M

$19K

$1T

63M

$28K

$2T

66M

$39K

$3T

Egypt

101M

$1T

$13K

$14K

117M

$17K

$2T

134M

$23K

$3T

151M

$29K

$4T

Vietnam

98M

$1T

$8K

$12K

105M

$12K

$1T

110M

$19K

$2T

113M

$28K

$3T

India

1389M

$12T

$8K

$8K

1528M

$13K

$20T

1634M

$18K

$30T

1705M

$26K

$44T

Philippines

108M

$1T

$10K

$10K

124M

$13K

$2T

137M

$17K

$2T

148M

$22K

$3T

Bangladesh

170M

$1T

$5K

$8K

186M

$7K

$1T

197M

$11K

$2T

202M

$15K

$3T

Pakistan

208M

$1T

$6K

$6K

245M

$8K

$2T

279M

$10K

$3T

310M

$14K

$4T

Nigeria

207M

$1T

$6K

$5K

263M

$7K

$2T

327M

$9K

$3T

399M

$11K

$4T

Mean/Sum

5851M

$116T

$28K

6251M

$34K

$155T

6545M

$42K

$202T

6740M

$51K

$259T

Discussion

In the GDP/cap forecasts above, one thing jumps out: in just 27 years, the world might be fundamentally changed. I find it illustrative to imagine yourself being 27 years older in a world where:

A richer world might also have:[9]

Generally, in 2050 we should expect the wealth gap between richer and poorer countries to be smaller. Poorer countries have been catching up with richer ones since the '90s[10] (but see[11]). They grow faster than rich countries because of fast catch-up or 'copy-and-paste' growth, whereas richer countries at the frontier can't grow as fast anymore since ideas are getting harder to find. This leads to convergence in countries' wealth. Looking at this in action: just 27 years ago, Lithuania's and Estonia's GDP/cap (PPP-adjusted) were ~⅓ of Japan's, but, surprisingly, now they're the same.[12] We might be surprised again in 27 years. Crucially, the changes ahead seem radically more dramatic than the changes between 27 years ago and now.

Values and Culture

What will people's values be in 2050? Since 1980, the West has moved away from 'obedient values' towards 'emancipative values' and became more internally homogenous.[13] Overall, the world is moving towards Western values, but non-Western nations are adopting different values at different speeds. Concretely, nations are de-emphasizing religion and moving from valuing obedience to valuing independence relatively quickly, but they are slower to adopt Western secular-rational and self-expression values, such as beliefs about homosexuality, abortion, divorce, prostitution, euthanasia, childhood obedience, and suicide. This leads to convergence of values in some areas and divergence in others.[14]

Much of the variation in values between societies can be explained by GDP/cap differences and boils down to two broad dimensions:[15]

Since richer people tend to favor secular-rational and self-expression values over traditionalist and survivalist values, we should expect people in 2050 to be more secular and more interested in self-expression than people today.

GDP growth has been argued to lead to 'Greater opportunity, tolerance of diversity, social mobility, commitment to fairness, and dedication to democracy.'[16] (but also more meat consumption[17]).

In 2050, people will be older, on average. From 1970 to 2022, the global median age has already increased from 20 to 30 years; it's projected to further increase to 36 by 2050. Unexpectedly, Chinese people will be older than people in the US and the EU.[18],[19] People become slightly more conservative as they age.[20]

In 'The World in 2050', McRae argues that ideas will flow more from east to west. China and other Asian nations' technological advancements will contribute to broader 'Easternisation', signifying a global power shift toward the East, just as the world was Europeanized in the 19th century and Americanized in the 20th century. Now, in the 21st century, due to fast catch-up and population growth, the world is being 'asianized'[21]).

McRae also claims that the anglosphere will become even more important: English-speaking countries will make up 40% of the world's GDP, and populous countries on many continents will be English-speaking (Americas: US; Africa: Nigeria; Asia: India; Oceania: Australia; Europe: British Isles).

Growth could be much faster

As mentioned above, this data offers a soft lower bound on how much the world could change over the next 26 years. In contrast, however, some have speculated that future growth could be extremely fast. For example, MacAskill writes:

'Given that growth rates have increased 30x since the agricultural era, it's not crazy to think that they might increase 10x again; but if they did, the world economy would double every 2.5 years.'[22]

Or relatedly, Karnovsky's 'Most Important Century' hypothesis[23] claims:

But here, in the business-as-usual near-future scenario, nothing has to go 'zoom'; this 'can go on', perhaps with only modest innovation, even without a transformative AI productivity boom and even if ideas are getting harder to find[24] or Chinese growth slows down.[25],[26] Such a future might even be recognizable to us today because we know what rich countries look like.

I am not arguing that the business-as-usual scenario is more likely than a transformative AI scenario that makes the world economy double every 2.5 years—I am merely making a weaker claim by suggesting that this 'lower bound' world is already surprisingly different from today (we could call it wild). Indeed, it might be this intermediate step of continued 'business as usual' growth that will lead to transformative AI (see below). This means that GDP/cap projections can also help us get a better sense of what the world could look like in the lead-up to transformative AI. And we have a better sense of how far the world will change, since we know how countries changed when they went from $10k to $40k per capita GDP. Experts suggest that there's more than a 10% chance of transformative AI by 2036 and a ~50% chance by 2060.[27] In the absence of catastrophes, it seems like that the inverse probability - 50% chance that we will be in live in this non-TAI world until 2060.

Implications for AI

GDP forecasts inform forecasts of global challenges (e.g. climate models depend on growth).[29] For instance, both OpenPhil and Epoch estimate that the most expensive AI training run will reach some limit based on economic constraints (i.e. 1% of US GDP).[30] I'll now discuss how AI might influence future GDP/cap figures, and vice versa.

AI causes growth: Most top economists think that AIs such as ChatGPT have a measurable impact on national innovation,[31] and many agree that AI will substantially boost EU/US per capita income over the next 30 years—perhaps more than the internet.[32],[33] Forecasts suggest that AI may increase the US growth rate by 0.6-3.6% until 2040[34] and annual global GDP by 7%.[35] Other economists argue against this and estimate an upper bound on GDP gains might be more modest at ~1.7% over the next 10 years.[36]

Growth might speed up AI development: If India's GDP/cap really grows from $8k to $26k (equivalent to Russia's today) and China's from $19k to $43k (equivalent to Japan's today), and if India and China have, relative to their population, as many researchers as Russia and Japan do today, then that would double today's global research force of 10M.[37] Demographics suggests that China will have ~11M college graduates of which ~half were STEM graduates per year until 2040, resulting in ~80M new STEM workers, and then decline due to falling fertility (cf. the US has a total of 16M graduates).[38]

Global R&D spending is currently ~$1T[39], and this might double if GDP more than doubles. Until 2015, the percentage of GDP spent on R&D was roughly constant at ~2%, but it's now 2.5%.[40] Even if returns to research diminish and new ideas are getting harder to find,[41] more funding might still speed up research effectively. Doubling the number of workers also increases the rate of idea production, and thus innovation. The non-rivalry of ideas means that someone can use an idea without impinging on someone else's use of that idea (e.g. your use of the chain rule doesn't prevent other people from using the chain rule). And so for R&D, doubling the inputs to production more than doubles output, as we adopt innovations created by others. Surprisingly, this effect is very large even if new ideas are getting much harder to find.[42]

A recent Epoch report[43] argues that the mid-20th century economic slowdown follows from the standard economic growth model and the demographic transition, which decoupled population growth from economic growth, leading to declining fertility and growth rates. In contrast, AI workforces can expand rapidly, as hardware manufacturing is not constrained like human population growth, and software can be copied cheaply, which allows the 'population' of AI workers to grow and innovate at the same time. Unless AI-driven growth is slowed, AI labor might increase the speed of growth a lot until physical bottlenecks stop this at very high levels of growth by current standards.

The three main first-order inputs for AI progress are:[44]

Doubling the global research force will likely mean more scientists and research engineers working on improving algorithmic efficiency and driving down prices for compute. Globally, ~2% of World 'GDP' or ~$2.4T/year will be spent on all R&D (~20% is spent on basic R&D, which has increased over time) [45],[46],[47] As a rule, the richer the country, the higher the share of GDP it spends on R&D.[48] For instance, US R&D is 3% of GDP.[49] The EU aims to increase combined public and private investment in R&D to 3.5% of GDP by 2025.[50] The UK wants to increase it to 2.4% of GDP by 2027.[51] (see roadmap[52]). NATO spends more than half of the ~$2T spent on the military globally.[53] NATO countries have agreed to spend 2% of GDP on defense by 2024; at least 20% of the 2% target should be spent on major equipment, including related military R&D. These international agreements are pegged to GDP. This means that their budgets (e.g. military, research) are coupled so that they increase in lockstep with GDP. If we grow GDP, which economies optimize for,[54] we automatically increase these budgets, which creates risks from emerging technologies like synthetic biology and AI. These dynamics are relevant to the principle of differential technological development.[55]

Will growth slow?

'Before the Industrial Revolution, it took many centuries for the world economy to double in size; now it doubles every twenty-five years [...] [Over the last fifty years, global GDP / person grew by 2% / year, and all major geographic areas are experiencing significant growth. Growth economists surveyed thought that this trend would stay broadly the same, at 2.1% / year]'[56]

World GDP growth seems to be slowing down from ~5% per year in the 1960's, to ~4% in the 70s, to ~3% in '80s, '90s, '00s, to ~2.5% in the 2010s. I naively extrapolated this trend[57] and found ~2% in 2030 and 1% in 2050:

This trend might continue, albeit more gradually:[58]

By 2027 GDP/cap growth in the median rich country will be <1.5% a year. In some countries, such as Canada and Switzerland, it might be ~0%.[59] Forecasts predict that growth will continue to slow for 'structural reasons such as aging populations, shifts from goods to services, slowing innovation, and debt.'[60] It might also be because scientific progress is slowing.[61] IT–related productivity increases explain 75% of all recent US productivity growth,[62] with similar results globally.[63]

While IT, new tech and an interconnected world may accelerate growth further, the effect might not be so huge: true, while big ideas advance the knowledge frontier, which transformed the West from 1870-1970, now growth has slowed (cf The Great Stagnation), and progress is harder with fewer low-hanging fruits, more complex knowledge and societal stagnation.[64]

But even if GDP percentage growth slows, wellbeing growth can still speed up, for two reasons:

Methods

Spreadsheet here.

I used three datasets for this analysis: PwC's 2017 simplified Solow growth model, Gapminder's 2021 model, and Goldman Sachs' 2022 model.

'Persistence' of growth

As always, note that these models are very crude and should not be taken literally, but they're preferable to leaving our assumptions about the future unarticulated, fuzzy, and vague.It is better to be wrong than vague, and to state explicit assumptions that can be questioned and falsified (as the common aphorisms in statistics go: 'Truth will sooner come out of error than from confusion', 'All models are wrong, but some are useful', 'You're not even wrong', 'It is better to be roughly right than precisely wrong', 'Better clear than clever', etc.). So, our models might be off, but they help us think through relevant considerations and formalize our intuitions. This very much applies here, since these models will very likely be off.

Some argue that it's hard to forecast GDP[69] and population growth[70], despite knowing all essential variables. But others show that, strikingly, some growth might be surprisingly persistent: in many rich countries, GDP/cap from 100 years ago predicts GDP/cap today well within a few percentage points, as average growth is usually ~2%.[71]

Relatedly, even though GDP doesn't measure welfare perfectly, it is one of the best predictors of welfare.[72] See also further links on GDP as a proxy for welfare below.

Future Research

Here are some research questions in this area that might be useful:

Appendix: Further reading

The World in 2050

In 1996, McRae published 'The World in 2020'. I only skimmed it but it seems like it makes some good predictions (e.g. Brexit, working from home, 'video phones', online retail), though crucially it seems to underestimate how central the internet was going to be. Now, 25 years later, he just published 'The World in 2050'[74]. Tl;dr:

Economics

GDP as a proxy for welfare

AI

Forecasting

Fiction

Appendix: Causal Model Between Growth, Liberal Democracy, Human Capital, Peace, and X-Risk

Below I have a rough and unfinished conceptual dynamic causal model between growth, liberal democracy, human capital, peace, and x-risk, that summarizes the evidence for their relationships.

Economic Growth causes…

Democracy causes...

Human capital causes…

Peace & stability causes...

Note that everything is correlated and an in-depth evidence review of 'Does X cause Y?' argues that 'We ultimately need to choose between (a) believing some overly complicated theory of the relationship between X and Y, which reconciles all of the wildly conflicting and often implausible things we're seeing in the studies; (b) more-or-less reverting to what we would've guessed about the relationship between X and Y in the absence of any research.'

How big a deal was the Industrial Revolution?

Growth and the case against randomista development

Mean vs. Median GDP/cap

Median and mean household disposable income - Our World in Data

GDP/cap, PPP (current international $) - Norway, Switzerland

List of countries by number of scientific and technical journal articles - Wikipedia

The Good Country Index

The World in 2050: How to Think About the Future

Long-standing historical dynamics suggest a slow-growth, high-inequality economic future

The new era of unconditional convergence

Converging to Converge? A Comment | NBER

Lithuania's GDP/cap might surpass Japan's next year

Worldwide divergence of values | Nature Communications

Are the World’s National Cultures Becoming More Similar?

https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSContents.jsp?CMSID=Findings&title=Anna

The Moral Consequences Of Economic Growth

Meat and Dairy Production - Our World in Data

OWID - Median age, 1970 to 2050

OWID - Median age, 1970 to 2050

Do People Really Become More Conservative as They Age? | The Journal of Politics

Parag Khanna: The Future Is Asian: Commerce, Conflict, and Culture in the 21 st Century

MacAskill - What We Owe The Future

The 'most important century' blog post series

Could Advanced AI Drive Explosive Economic Growth? - Open Philanthropy

China Slowdown Means It May Never Overtake US Economy, Forecast Shows

Will China's economy overcome the US | Capital Economics

A public prediction by Holden Karnofsky | Metaculus

The Future of Humanity

Multidecadal dynamics project slow 21st-century economic growth and income convergence

https://epochai.org/blog/trends-in-the-dollar-training-cost-of-machine-learning-systems#fnref:34

AI, Innovation and Society–Clark Center Forum

AI and Productivity Growth - Clark Center Forum

AI and Productivity Growth 2 - Clark Center Forum

The economic potential of generative AI

The Potentially Large Effects of Artificial Intelligence on Economic Growth (Briggs/Kodnani)

The Simple Macroeconomics of AI by Daron Acemoglu

Researchers in R&D (per million people)

India calculation

China calculation

https://twitter.com/hsu_steve/status/1623279827640848385

Research and development (R&D) - Gross domestic spending on R&D - OECD

https://twitter.com/benjamin_hilton/status/1703719047030874300

Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find?

Explosive growth from AI automation: A review of the arguments

A Compute-Based Framework for Thinking About the Future of AI – Epoch.

The AI Triad and What It Means for National Security Strategy

Global R&D investments unabated in spending growth - Research & Development World

Global Research and Development Expenditures: Fact Sheet

Global Investments in R&D - 2019

How Much Science? - Economic Policy

New Data Says U.S. R&D Has Topped 3% of GDP For the First Time Ever

EUROPE 2020: A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth

Increasing investment in R&D to 2.4% of GDP

UK Research and Development Roadmap

Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2019

How much economic growth is necessary to reduce global poverty substantially? - Our World in Data

Differential Technology Development: A Responsible Innovation Principle for Navigating Technology Risks

MacAskill - What We Owe The Future

GDP growth forecasts

The Path to 2075 — Slower Global Growth, But Convergence Remains Intact | Goldman

How the West fell out of love with economic growth | The Economist

How the West fell out of love with economic growth

[Podcast] Is scientific progress slowing? with James Evans

A Retrospective Look at the US Productivity Growth Resurgence

Information Technology and the World Economy

Michael Bhaskar. Human Frontiers: The Future of Big Ideas in an Age of Small Thinking (2021)- James Aitchison

What kind of 'growth' slowdowns should we care about?

The value of money going to different groups

The Long View: How will the global economic order change by 2050?

GDP/cap in constant PPP dollars | Gapminder

The Signal and the Noise

From Microorganisms to Megacities

Developing the guts of a GUT (Grand Unified Theory): elite commitment and inclusive growth

Growth and the case against randomista development

https://globalprioritiesinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/gpi-research-agenda.pdf

The World in 2050

Fun Economic Facts - Alexey Guzey

How the World Really Works: The Science Behind How We Got Here and Where We're Going

Evidence from 33 countries challenges the assumption of unlimited wants | Nature Sustainability

'Most important century' series: roadmap

Notes - What We Owe the Future

Forecasting the dividends of conflict prevention from 2020 - 2030

World values survey