... i.e., it doesn't spend enough time arguing about object-level things.

The way I'm using it in this post, "object-level" might include these kinds of things:

- While serving as Secretary of State, did Hillary Clinton send classified information to an insecure email server? How large was the risk that attackers might get the information, and how much harm might that cause?

- What are the costs and benefits of various communications protocols (e.g., the legal one during Clinton's tenure, the de facto one Clinton followed, or other possibilities), and how should we weight those costs and benefits?

- How can we best forecast people's reliability on security issues? Are once-off mistakes like this predictive of future sloppiness? Are there better ways of predicting this?

"Meta" might include things like:

- How much do voters care about Clinton's use of her email server?

- How much will reporters cover this story, and how much is their coverage likely to influence voters?

- What do various people (with no special information or expertise) believe about Clinton's email server, and how might these beliefs change their behavior?

I'll also consider discussions of abstract authority, principle, or symbolism more "meta" than concrete policy proposals and questions of fact.

This is too meta:

Meta stuff is real. Elections are real, and matter. Popularity, status, controversy, and Overton windows have real physical effects.

But it's possible to focus too much on one part of reality and neglect another. If you're driving a car while talking on the phone, the phone and your eyes are both perfectly good information channels; but if you allocate too little attention to the road, you still die.

When speaking the demon's name creates the demon

I claim:

There are many good ideas that start out discussed by blogs and journal articles for a long time, then get adopted by policymakers.

In many of these cases, you could delay adoption by many years by adding more sentences to the blog posts noting the political infeasibility or controversialness of the proposal. Or you could hasten adoption by making the posts just focus on analyzing the effects of the policy, without taking a moment to nervously look over their shoulder, without ritually bowing to the Overton window as though it were an authority on immigration law.

I also claim that this obeys the same basic causal dynamics as:

My friend Azzie posts something that I find cringe. So I decide to loudly and publicly (!) warn Azzie "hey, the thing you're doing is cringe!". Because, y'know, I want to help.

Regardless of how "cringe" the average reader would have considered the post, saying it out loud can only help strengthen the perceived level of cringe.

Or, suppose Bel overhears me and it doesn't cause her to see the post as more cringe. Still, it might make Bel worry that Cathy and other third parties think that the post is cringe. Which is a sufficient worry on its own to greatly change how Bel interacts with the post. Wouldn't want the cringe monster to come after you next!

This can result in:

Non-well-founded gaffes: statements that are controversial/offensive/impolitic largely or solely because some people think they sound like the kind of thing that would offend, alienate, or be disputed by a hypothetical third party.

Or, worse:

Even-less-than-non-well-founded gaffes: statements that are controversial/offensive/impolitic largely or solely because some people are worried that a hypothetical third party might think that a hypothetical fourth party might be offended, alienated, or unconvinced by the statement.

See: Common Knowledge and Miasma.

See: mimesis, herding, bystander effect, conformity instincts, coalitional instincts, and The World Forager Elite.

Regardless of how politically unfeasible the policy proposal would have been, saying that it's unfeasible will tend to make it more unfeasible. Others will pick up on the social cue and be more cautious about promoting the idea; which causes others to imitate them and be more cautious, and will cause the idea to spread less. Which makes people nervously look around for proof that this is a mainstream-enough idea when they first hear about it.

This strikes me as one of the main ways that groups can end up stupider than their members, and civilizations can end up neglecting low-hanging fruit.

Brainstorming and trying things

Objection: "Political feasibility matters. There may be traps and self-fulfilling prophecies here; but if we forbid ourselves from talking about it altogether, we'll be ignoring a real and important part of the world, which doesn't sound like the right way to optimize."

My reply: I agree with this.

But:

- I think mainstream political discourse is focusing on this way too much, as of 2021.

- I think people should be more cautious about when and how they bring in political feasibility, especially in the early stages of evaluating and discussing ideas.

- I think the blog posts discussing "would this be a good policy if implemented?" should mostly be separate from the ones discussing "how politically hard would it be to get this implemented?".

Objection: "But if I mention feasibility in my initial blog post on UBI, it will show that I'm a reasonable and practical sort of person, not a crackpot who's fallen in love with pie-in-the-sky ideas."

My reply: I can't deny that this is a strategy that can be helpful.

But there are other ways to demonstrate reasonableness that have smaller costs. Even just saying "I'm not going to talk about political feasibility in this post" can send an adequate signal: "Yes, I recognize this is a constraint at all. I'm treating this topic as out-of-scope, not as unimportant." Though even saying that much, I worry, can cause readers' thoughts to drift too much away from the road.

Policies' popularity (frequently) matters. But often the correct response to seeing a good idea that looks plausibly-unfeasible is to go "oh, this is a good idea", help bring a huge wave of energy and enthusiasm to bear on the idea, and try your best to get it discussed and implemented, to find out how feasible it is.

We're currently in a world where most good ideas fail. But... failing is mostly fine? See On Doing the Improbable and Anxious Underconfidence.

Newer, weirder, and/or more ambitious ideas in particular can often seem too "out there" to ever get traction. Then a few years later, everyone's talking about UBI. That feeling of anxious uncertainty is not actually a crystal ball; better to try things and see what happens.

Ungrounded social realities are fragile

From Inadequate Equilibria:

[...] The still greater force locking bad political systems into place is an equilibrium of silence about policies that aren’t “serious.”

A journalist thinks that a candidate who talks about ending the War on Drugs isn’t a “serious candidate.” And the newspaper won’t cover that candidate because the newspaper itself wants to look serious… or they think voters won’t be interested because everyone knows that candidate can’t win, or something? Maybe in a US-style system, only contrarians and other people who lack the social skill of getting along with the System are voting for Carol, so Carol is uncool the same way Velcro is uncool and so are all her policies and ideas? I’m not sure exactly what the journalists are thinking subjectively, since I’m not a journalist. But if an existing politician talks about a policy outside of what journalists think is appealing to voters, the journalists think the politician has committed a gaffe, and they write about this sports blunder by the politician, and the actual voters take their cues from that. So no politician talks about things that a journalist believes it would be a blunder for a politician to talk about. The space of what it isn’t a “blunder” for a politician to talk about is conventionally termed the “Overton window.”

[...] To name a recent example from the United States, [this] explains how, one year, gay marriage is this taboo topic, and then all of a sudden there’s a huge upswing in everyone being allowed to talk about it for the first time and shortly afterwards it’s a done deal.

[... W]e can say, “An increasing number of people over time thought that gay marriage was pretty much okay. But while that group didn’t have a majority, journalists modeled a gay marriage endorsement as a ‘gaffe’ or ‘unelectable’, something they’d write about in the sports-coverage overtone of a blunder by the other team—”

[...] The support level went over a threshold where somebody tested the waters and got away with it, and journalists began to suspect it wasn’t a political blunder to support gay marriage, which let more politicians speak and get away with it, and then the change of belief about what was inside the Overton window snowballed.

And:

What broke the silence about artificial general intelligence (AGI) in 2014 wasn’t Stephen Hawking writing a careful, well-considered essay about how this was a real issue. The silence only broke when Elon Musk tweeted about Nick Bostrom’s Superintelligence, and then made an off-the-cuff remark about how AGI was “summoning the demon.”

Why did that heave a rock through the Overton window, when Stephen Hawking couldn’t? Because Stephen Hawking sounded like he was trying hard to appear sober and serious, which signals that this is a subject you have to be careful not to gaffe about. And then Elon Musk was like, “Whoa, look at that apocalypse over there!!” After which there was the equivalent of journalists trying to pile on, shouting, “A gaffe! A gaffe! A… gaffe?” and finding out that, in light of recent news stories about AI and in light of Elon Musk’s good reputation, people weren’t backing them up on that gaffe thing.

Similarly, to heave a rock through the Overton window on the War on Drugs, what you need is not state propositions (although those do help) or articles in The Economist. What you need is for some “serious” politician to say, “This is dumb,” and for the journalists to pile on shouting, “A gaffe! A gaffe… a gaffe?” But it’s a grave personal risk for a politician to test whether the public atmosphere has changed enough, and even if it worked, they’d capture very little of the human benefit for themselves.

The public health response to COVID-19 has with surprising consistency been a loop of:

- Someone like Marc Lipsitch or Alex Tabarrok gives a good argument for X (e.g., "the expected value of having everyone wear masks is quite high").

- Lots of people spring up to object, but the objections seem all-over-the-place and none of them seem to make sense.

- Time passes, and eventually a prestigious institution endorses X.

- Everyone who objected to X now starts confabulating arguments in support of X instead.

I think this is a pretty socially normal process. But usually it's a slow process. Seeing the Overton window and "social reality" change with such blinding speed has helped me better grok this dynamic.

Additionally, something about this process seems to favor faux certainty and faux obliviousness over expected-value-style thinking.

Zvi Mowshowitz discusses a hypothetical where Biden does something politically risky, and suffers so much fallout that it cripples his ability to govern. Then Zvi adds:

Or at least, that’s The Fear.

The Fear does a lot of the work.

It’s not that such things would actually definitely happen. It’s that there’s some chance they might happen, and thus no one dares find out.

[... W]hen you’re considering changing from policy X to policy Y, you’re being judged against the standard of policy X, so any change is blameworthy. How irresponsible to propose First Doses First.

But…

A good test is to ask, when right things are done on the margin, what happens? When we move in the direction of good policies or correct statements, how does the media react? How does the public react?

This does eventually happen on almost every issue.

The answer is almost universally that the change is accepted. The few who track such things praise it, and everyone else decides to memory hole that we ever claimed or advocated anything different. We were always at war with Eastasia. Whatever the official policy is becomes the null action, so it becomes the Very Serious Person line, which also means that anyone challenging that is blameworthy for any losses and doesn’t get credit for any improvements.

This is a pure ‘they’ll like us when we win.’ Everyone’s defending the current actions of the powerful in deference to power. Change what power is doing, and they’ll change what they defend. We see it time and again. Social distancing. Xenophobia. Shutdowns. Masks. Better masks. Airborne transmission. Tests. Vaccines. Various prioritization schemes. First Doses First. Schools shutting down. Schools staying open. New strains. The list goes on.

There are two strategies. We can do what we’re doing now, and change elite or popular opinion to change policy. Or we can change policy, and in so doing change opinion leaders and opinion.

This is not to say that attempts to shift (or route around) the Overton window will necessarily have a high success rate.

But it is to say:

- Some of the factors influencing this success rate have the character of a self-fulfilling prophecy. And such prophecies can be surprisingly fragile.

- The Overton window distorts thinking in ways that can make it harder to estimate success rates. The current political consensus just feels like 'what's normal', 'what's reasonable', 'what's acceptable', and the fact that this is in many ways a passing fad is hard to appreciate in one's viscera. (At least, it's hard for me; it might be easy for you.)

(I also happen to suspect that some very recent shifts in politics and culture have begun to make Overton windows easier to break and made "PR culture" less adaptive to the new climate. But this is a separate empirical claim that would probably need its own post-length treatment.)

Steering requires looking at the road

I claim that politics is too meta.

(I would also say that, e.g., effective altruist discourse spends too much time on meta. And a lot of other discourses besides.)

Going overboard on meta is bad because:

- It can create or perpetuate harmful social realities that aren't based in any external reality.

- It can create (or focus attention on) social realities that actively encourage false beliefs (including false beliefs that make it harder to break the spell).

- It's unnecessary. Often the idea that we need to spend a lot of time on meta is itself a self-perpetuating myth, and we can solve problems more effectively by just trying to solve the problem.

- It makes it harder to innovate.

- It makes it harder to experiment and make high-EV bets.

It's also bad because it's distracting.

Distraction is a lot more awful than it sounds. If you go from spending 0% of your time worrying about the hippopotamus in your bathtub to spending 80% of your time worrying about it, your other life-priorities will probably suffer quite a bit even if the hippo doesn’t end up doing any direct damage.

And it would be quite bad if 15% of the cognition in the world were diverted to hippos.

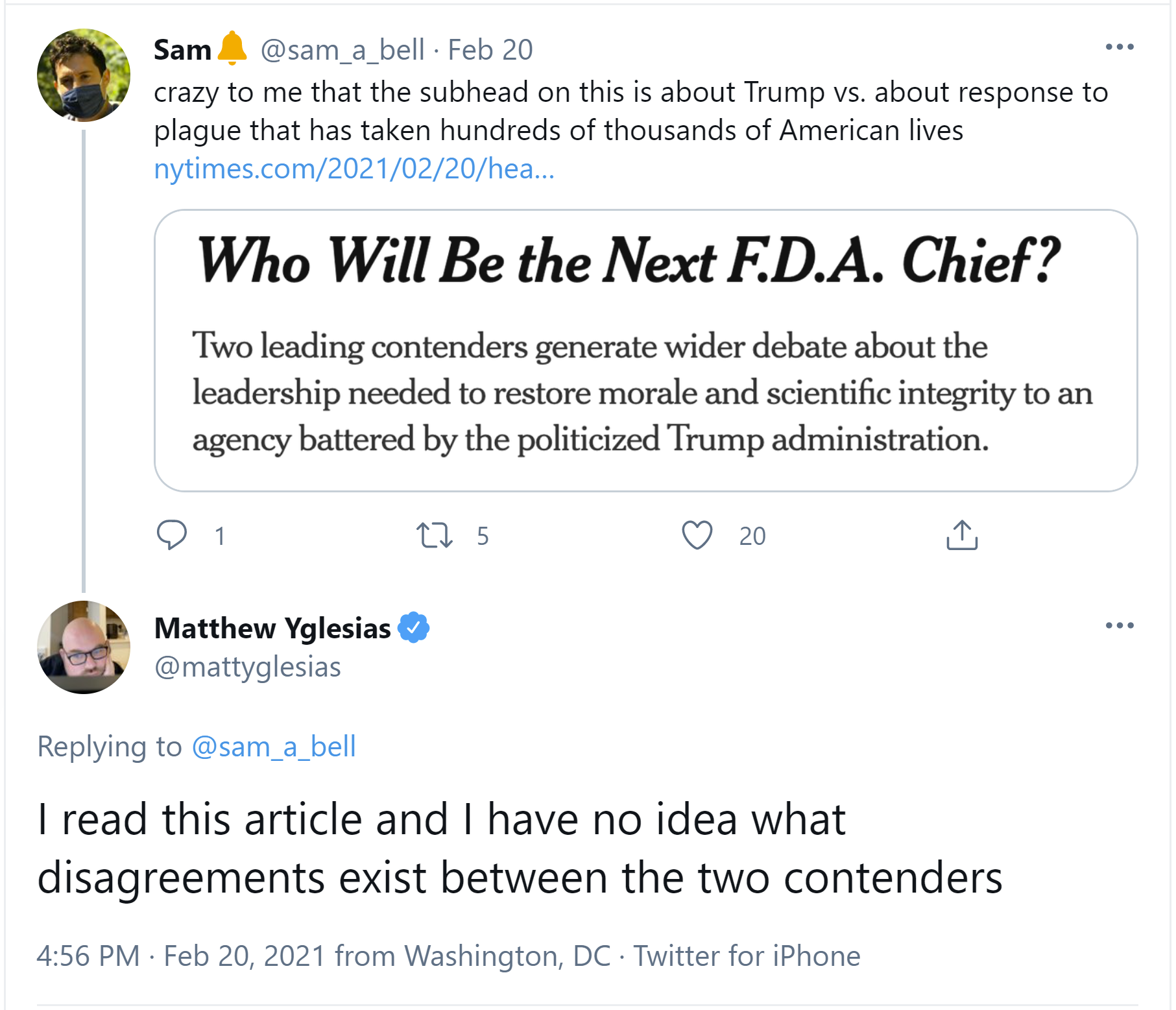

Note the headlines' framings. The New York Times is creating a social reality by picking which stories to put on its front page, but all the reporting is also about social realities: "How will this information (that we are here reporting on) change what's controversial, what's popular, what's believed, etc., and thereby affect the election?"

Presidential elections are a time when it's especially tempting to go meta, since we're all so curious about us, about how we'll vote. But they're also a time when it's an especially terrible idea to go meta, because our models and behavior are unusually important at this time and this is the exact time when we most need to be thinking about the object-level tradeoffs in order to make a higher-quality decision.

Imagine trying to steer a ship by polling the crew members, but then covering over all the ship's windows and doors with real-time polling data.

I don't think the reporters and editors here feel like they're doing the "loudly and publicly warn someone that they're being cringe" thing, or the "black out the ship's windows with polling data" thing. But that's what's happening, somehow.

If the emails are important in their own right, then great! The headlines and articles can be all about their object-level importance. Help voters make a maximally informed decision about the details of this person's security practices and how these translate into likely future behavior.

Headlines can focus on object-level details and expert attempts to model individuals' rule-following behavior. You can even do head-to-head comparisons of object-level differences about the people running for president!

But the front-page articles really shouldn't be about the controversy, the buzz, the second-order perceptions and spin and perceptions-of-spin. The buzz is built out of newspaper articles, and you want the resultant building to stand on some foundation; you don't want it to be a free-floating thing built on itself.

The articles shouldn't drool over the tantalizingly influenceable/predictable beliefs and attitudes of the people reading the articles. Internal decisions about the topic's importance (and the angle and focus of the coverage) shouldn't rest on hypothetical perceptions of the news coverage. "It's important because it will affect voters' beliefs because we're reporting that it's important because it will affect voters' b..."

This is an extreme example, but I'm mostly worried about the mild examples, because small daily hippos are worse than large rare hippos.

"A major win for Biden" here isn't just trying to give credit where credit's due; it's drawing attention to one of the big interesting things about this $1.9 trillion bill, which is its effect on Biden's future popularity (and thereby, maybe just maybe, the future balance of political power).

This is certainly one of the interesting things about bills, and I could imagine a college class that went through bill after bill and assessed it mainly through the frame of "who's winning, the Republicans or the Democrats?", which might teach some interesting things.

But "who's winning?" isn't the only topic you could teach in a college course by walking through a large number of historical bills.

So why has every major news outlet in the US settled on "who's winning" as the one true frame for public policy coverage? Is this what we'd pick if we were making a conscious effort to install good norms, or is it just a collective bad habit we've fallen into?

If you don't look at the road while you're driving, you get worse decision-making, and the polarization ratchet continues, and we all get dumber and more sports-fan-ish.

My political views have changed in a big way a few times over the years. In each case, the main things that caused me to update weren't people yelling their high-level principles at me more insistently. I was persuaded by being hit over the head repeatedly with specific object-level examples showing I was wrong about which factual claims tend to be true and which tend to be false.

If you want to produce good outcomes from nations, try arguing more about actual disagreements people have. Policy isn't built out of vibes or branding any more than a car engine is.

For me, this perfectly hits the nail on the head.

This is a somewhat weird question, but like, how do I do that?

I've noticed multiple communities fall into the meta-trap, and even when members notice it can be difficult to escape. While the solution is simply to "stop being meta", that is much harder said than done.

When I noticed this happening in a community I am central in organizing I pushed back by bringing my own focus to output instead of process hoping others would follow suit. This has worked somewhat and we're definitely on a better track. I wonder what dynamics lead to this 'death by meta' syndrome, and if there is a cure.