Followup to: Timeless Physics

Julian Barbour believes that each configuration, each individual point in configuration space, corresponds individually to an experienced Now—that each instantaneous time-slice of a brain is the carrier of a subjective experience.

On this point, I take it upon myself to disagree with Barbour.

There is a timeless formulation of causality, known to Bayesians, which may glue configurations together even in a timeless universe. Barbour may not have studied this; it is not widely studied.

Such causal links could be required for "computation" and "consciousness"—whatever those are. If so, we would not be forced to conclude that a single configuration, encoding a brain frozen in time, can be the bearer of an instantaneous experience. We could throw out time, and keep the concept of causal computation.

There is an old saying: "Correlation does not imply causation." I don't know if this is my own thought, or something I remember hearing, but on seeing this saying, a phrase ran through my mind: If correlation does not imply causation, what does?

Suppose I'm at the top of a canyon, near a pile of heavy rocks. I throw a rock over the side, and a few seconds later, I hear a crash. I do this again and again, and it seems that the rock-throw, and the crash, tend to correlate; to occur in the presence of each other. Perhaps the sound of the crash is causing me to throw a rock off the cliff? But no, this seems unlikely, for then an effect would have to precede its cause. It seems more likely that throwing the rock off the cliff is causing the crash. If, on the other hand, someone observed me on the cliff, and saw a flash of light, and then immediately afterward saw me throw a rock off the cliff, they would suspect that flashes of light caused me to throw rocks.

Perhaps correlation, plus time, can suggest a direction of causality?

But we just threw out time.

You see the problem here.

Once, sophisticated statisticians believed this problem was unsolvable. Many thought it was unsolvable even with time. Time-symmetrical laws of physics didn't seem to leave room for asymmetrical causality. And in statistics, nobody thought there was any way to define causality. They could measure correlation, and that was enough. Causality was declared dead, and the famous statistician R. A. Fisher testified that it was impossible to prove that smoking cigarettes actually caused cancer.

Anyway...

Let's say we have a data series, generated by taking snapshots over time of two variables 1 and 2. We have a large amount of data from the series, laid out on a track, but we don't know the direction of time on the track. On each round, the past values of 1 and 2 probabilistically generate the future value of 1, and then separately probabilistically generate the future value of 2. We know this, but we don't know the actual laws. We can try to infer the laws by gathering statistics about which values of 1 and 2 are adjacent to which other values of 1 and 2. But we don't know the global direction of time, yet, so we don't know if our statistic relates the effect to the cause, or the cause to the effect.

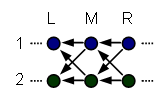

When we look at an arbitrary value-pair and its neighborhood, let's call the three slices L, M, and R for Left, Middle, and Right.

We are considering two hypotheses. First, that causality could be flowing from L to M to R:

Second, that causality could be flowing from R to M to L:

As good Bayesians, we realize that to distinguish these two hypotheses, we must find some kind of observation that is more likely in one case than in the other. But what might such an observation be?

We can try to look at various slices M, and try to find correlations between the values of M, and the values of L and R. For example, we could find that when M1 is in the + state, that R2 is often also in the + state. But is this because R2 causes M1 to be +, or because M1 causes R2 to be +?

If throwing a rock causes the sound of a crash, then the throw and the crash will tend to occur in each other's presence. But this is also true if the sound of the crash causes me to throw a rock. So observing these correlations does not tell us the direction of causality, unless we already know the direction of time.

From looking at this undirected diagram, we can guess that M1 will correlate to L1, M2 will correlate to R1, R2 will correlate to M2, and so on; and all this will be true because there are lines between the two nodes, regardless of which end of the line we try to draw the arrow upon. You can see the problem with trying to derive causality from correlation!

Could we find that when M1 is +, R2 is always +, but that when R2 is +, M1 is not always +, and say, "M1 must be causing R2"? But this does not follow. We said at the beginning that past values of 1 and 2 were generating future values of 1 and 2 in a probabilistic way; it was nowhere said that we would give preference to laws that made the future deterministic given the past, rather than vice versa. So there is nothing to make us prefer the hypothesis, "A + at M1 always causes R2 to be +" to the hypothesis, "M1 can only be + in cases where its parent R2 is +".

Ordinarily, at this point, I would say: "Now I am about to tell you the answer; so if you want to try to work out the problem on your own, you should do so now." But in this case, some of the greatest statisticians in history did not get it on their own, so if you do not already know the answer, I am not really expecting you to work it out. Maybe if you remember half a hint, but not the whole answer, you could try it on your own. Or if you suspect that your era will support you, you could try it on your own; I have given you a tremendous amount of help by asking exactly the correct question, and telling you that an answer is possible.

...

So! Instead of thinking in terms of observations we could find, and then trying to figure out if they might distinguish asymmetrically between the hypotheses, let us examine a single causal hypothesis and see if it implies any asymmetrical observations.

Say the flow of causality is from left to right:

Suppose that we do know L1 and L2, but we do not know R1 and R2. Will learning M1 tell us anything about M2?

That is, will we observe the conditional dependence

P(M2|L1,L2) ≠ P(M2|M1,L1,L2)

to hold? The answer, on the assumption that causality flows to the right, and on the other assumptions previously given, is no. "On each round, the past values of 1 and 2 probabilistically generate the future value of 1, and then separately probabilistically generate the future value of 2." So once we have L1 and L2, they generate M1 independently of how they generate M2.

But if we did know R1 or R2, then, on the assumptions, learning M1 would give us information about M2. Suppose that there are siblings Alpha and Betty, cute little vandals, who throw rocks when their parents are out of town. If the parents are out of town, then either Alpha or Betty might each, independently, decide to throw a rock through my window. If I don't know whether a rock has been thrown through my window, and I know that Alpha didn't throw a rock through my window, that doesn't affect my probability estimate that Betty threw a rock through my window—they decide independently. But if I know my window is broken, and I know Alpha didn't do it, then I can guess Betty is the culprit. So even though Alpha and Betty throw rocks independently of each other, knowing the effect can epistemically entangle my beliefs about the causes.

Similarly, if we didn't know L1 or L2, then M1 should give us information about M2, because from the effect M1 we can infer the state of its causes L1 and L2, and thence the effect of L1/L2 on M2. If I know that Alpha threw a rock, then I can guess that Alpha and Betty's parents are out of town, and that makes it more likely that Betty will throw a rock too.

Which all goes to say that, if causality is flowing from L to M to R, we may indeed expect the conditional dependence

P(M2|R1,R2) ≠ P(M2|M1,R1,R2)

to hold.

So if we observe, statistically, over many time slices:

P(M2|L1,L2) = P(M2|M1,L1,L2)

P(M2|R1,R2) ≠ P(M2|M1,R1,R2)

Then we know causality is flowing from left to right; and conversely if we see:

P(M2|L1,L2) ≠ P(M2|M1,L1,L2)

P(M2|R1,R2) = P(M2|M1,R1,R2)

Then we can guess causality is flowing from right to left.

This trick used the assumption of probabilistic generators. We couldn't have done it if the series had been generated by bijective mappings, i.e., if the future was deterministic given the past and only one possible past was compatible with each future.

So this trick does not directly apply to reading causality off of Barbour's Platonia (which is the name Barbour gives to the timeless mathematical object that is our universe).

However, think about the situation if humanity sent off colonization probes to distant superclusters, and then the accelerating expansion of the universe put the colonies over the cosmological horizon from us. There would then be distant human colonies that could not speak to us again: Correlations in a case where light, going forward, could not reach one colony from another, or reach any common ground.

On the other hand, we would be very surprised to reach a distant supercluster billions of light-years away, and find a spaceship just arriving from the other side of the universe, sent from another independently evolved Earth, which had developed genetically compatible indistinguishable humans who speak English. (A la way too much horrible sci-fi television.) We would not expect such extraordinary similarity of events, in a historical region where a ray of light could not yet have reached there from our Earth, nor a ray of light reached our Earth from there, nor could a ray of light reached both Earths from any mutual region between. On the assumption, that is, that rays of light travel in the direction we call "forward".

When two regions of spacetime are timelike separated, we cannot deduce any direction of causality from similarities between them; they could be similar because one is cause and one is effect, or vice versa. But when two regions of spacetime are spacelike separated, and far enough apart that they have no common causal ancestry assuming one direction of physical causality, but would have common causal ancestry assuming a different direction of physical causality, then similarity between them... is at least highly suggestive.

I am not skilled enough in causality to translate probabilistic theorems into bijective deterministic ones. And by calling certain similarities "surprising" I have secretly imported a probabilistic view; I have made myself uncertain so that I can be surprised.

But Judea Pearl himself believes that the arrows of his graphs are more fundamental than the statistical correlations they produce; he has said so in an essay entitled "Why I Am Only A Half-Bayesian". Pearl thinks that his arrows reflect reality, and hence, that there is more to inference than just raw probability distributions. If Pearl is right, then there is no reason why you could not have directedness in bijective deterministic mappings as well, which would manifest in the same sort of similarity/dissimilarity rules I have just described.

This does not bring back time. There is no t coordinate, and no global now sweeping across the universe. Events do not happen in the past or the present or the future, they just are. But there may be a certain... asymmetric locality of relatedness... that preserves "cause" and "effect", and with it, "therefore". A point in configuration space would never be "past" or "present" or "future", nor would it have a "time" coordinate, but it might be "cause" or "effect" to another point in configuration space.

I am aware of the standard argument that anything resembling an "arrow of time" should be made to stem strictly from the second law of thermodynamics and the low-entropy initial condition. But if you throw out causality along with time, it is hard to see how a low-entropy terminal condition and high-entropy initial condition could produce the same pattern of similar and dissimilar regions. Look at in another way: To compute a consistent universe with a low-entropy terminal condition and high-entropy initial condition, you have to simulate lots and lots of universes, then throw away all but a tiny fraction of them that end up with low entropy at the end. With a low-entropy initial condition, you can compute it out locally, without any global checks. So I am not yet ready to throw out the arrowheads on my arrows.

And, if we have "therefore" back, if we have "cause" and "effect" back—and science would be somewhat forlorn without them—then we can hope to retrieve the concept of "computation". We are not forced to grind up reality into disconnected configurations; there can be glue between them. We can require the amplitude relations between connected volumes of configuration space, to carry out some kind of timeless computation, before we decide that it contains the timeless Now of a conscious mind. We are not forced to associate experience with an isolated point in configuration space—which is a good thing from my perspective, because it doesn't seem to me that a frozen brain with all the particles in fixed positions ought to be having experiences. I would sooner associate experience with the arrows than the nodes, if I had to pick one or the other! I would sooner associate consciousness with the change in a brain than with the brain itself, if I had to pick one or the other.

This also lets me keep, for at least a little while longer, the concept of a conscious mind being connected to its future Nows, and anticipating some future experiences rather than others. Perhaps I will have to throw out this idea eventually, because I cannot seem to formulate it consistently; but for now, at least, I still cannot do without the notion of a "conditional probability". It still seems to me that there is some actual connection that makes it more likely for me to wake up tomorrow as Eliezer Yudkowsky, than as Britney Spears. If I am in the arrows even more than the nodes, that gives me a direction, a timeless flow. This may possibly be naive, but I am sticking with it until I can jump to an alternative that is less confusing than my present confused state of mind.

Don't think that any of this preserves time, though, or distinguishes the past from the future. I am just holding onto cause and effect and computation and even anticipation for a little while longer.

Part of The Quantum Physics Sequence

Next post: "Timeless Identity"

Previous post: "Timeless Beauty"

No, because there are no causal relationships, or relationships at all, within the randomly generated memory. If all you know is the prior distribution, not that the large-scale structure is in fact meaningful, there's no mutual information between any of the bits; and even once you know all the bits, since they're independent and random you can't say "this bit is 1 because this bit is 0."

This all smells of Mind Projection Fallacy, now that I think about it.