tech trees

There's a series of strategy games called Civilization. In those games, the player controls a country which grows and develops over thousands of years, and science is one of the main types of progress. It involves building facilities to generate research points, sometimes represented by Science Beakers filled with Science Fluid, and using those points to buy tech nodes on a tree.

I'm reminded of the above game mechanic when I see certain comments on blogs or Twitter/X. I'll use supersonic aircraft as an example.

supersonic aircraft

Several times, I've seen comments online similar to: "Look at this graph of aircraft speeds going up and then stopping. People should be forced to deal with sonic booms so we can have supersonic aircraft and get back to progress. It will be unpopular but this is more important than democracy."

In their mind, society has a "tech node" called "supersonic flight" and you need to finish the node before you can move to the next node. If opponents cause society to not finish the node, then you're stuck. But that's not how tech progress works. How much further would we be from supersonic transports today if the Concorde had never flown? The answer is 0.

There's a lot of underlying progress required for something like, say, a high-performance gas turbine. The abstract progress is more general, and each practical application involves different specifics. Understanding principles of metallurgy and how to examine metals leads to specific high-temperature alloys, which are what actually get used. Funding for gas turbine development can lead to single-crystal casting or turbine blade film cooling being developed, but the actual production of a new gas turbine model has no effect on whether that's developed.

The tech tree of a game like Civilization would be more accurate if it had a 3rd dimension, with height representing the abstract and general vs the practical and specific. Something like the Concorde would be on a vertical offshoot off the tree. But game systems representing something complex are simplified in ways that appeal to players.

Similarly, Boom Technology Inc working on a prototype for a supersonic plane does zero to bring the world closer to economically practical supersonic transport, because the underlying technology for that isn't there and they're not working on it. The best-case scenario for something like Boom Technology isn't "cheap supersonic flight", it's "a new resource-consuming luxury for rich people to spend money on that also makes the lives of most people a bit worse", or perhaps "a supersonic military UAV".

Similarly, I've seen people make charts of progress on humanoid robots that go like:

early robot 🡲 ASIMO 🡲 Atlas from Boston Dynamics 🡲 new thing

But ASIMO had no impact on later development of humanoid robots, and Boston Dynamics didn't invent the actuators used in their new robots or contribute to the modern neural network designs now used for computer vision. What was important was development of the underlying technologies: lightweight electric motors, power electronics, batteries, high-torque actuators, processors, and machine learning algorithms. To the extent that there's a "tech tree" involved, it's a fractal tree where the "nodes" are arcane things like semiconductor processing steps.

Trying to implement something when the underlying tech to make it practical isn't there yet can sometimes actually delay usage of it. To investors, "hasn't been tried" sounds a lot better than "was tried already and failed".

civics trees

Japan was the future but it's stuck in the past.

— the BBC

In Civilization 6, there are 2 separate tech trees, 1 for science and 1 for cultural development.

Sometimes you see people who want to ban all cars in all cities. It's not "I want to live in a city where I don't have to drive", it's "We need to change all cities so cars aren't used for transporting people, because that's The Future." Like they want to finish the "post-car cities" civic node.

To someone mainly concerned with tech progress, every regulation obstructing finishing the next tech node has to be torn down. But to someone mainly concerned with social technology, saying "regulations are bad because they don't let tech people do what they want" is like saying "pipes are bad because they don't let fluids do what they want".

If tech trees can only go forwards, then every change is progress. If change can only happen along tech trees, then the only options are "return to the previous node" and "advance to the next node". This is the fundamental similarity between the "tech tree" and "civics tree" people.

Sometimes you get people whose ideas of progress are linear and contradictory at some point, and then they have to fight endlessly over progress towards the "nuclear abolition civic" node vs progress towards the "advanced nuclear power tech" node. And then if you say something like "nuclear plants can be safe but the fans of them don't take safety seriously enough" or "nuclear waste is manageable but nuclear power is currently too expensive for reasons other than unnecessary regulations" then it only makes you enemies on both sides, because even if you partly agree with them you're still in the way of what they want to do.

Science Beakers

The other aspect of research in Civilization games I wanted to talk about was the "research points". A lot of people really do have this idea that professors and grad students basically fill up Science Beakers with Science Fluid and then the Scientific Process converts the Science Beakers into Progress.

People can think of research that way while understanding there's randomness, that perhaps only a fraction of research ultimately matters, but they think of that like gambling, like trying to pull "New medicine developed!" in a gacha game. That's not my experience. More experiments can collect more data, but if there's already enough data, then getting more data doesn't help you put the right data together into a concept. And research trying to prove the Amyloid Hypothesis of Alzheimer's doesn't help you understand what's actually going on.

You also can't feed your Science Beakers to The Scientific Process, because there is no Scientific Process that every scientist uses. There are just cultures of scientific fields, and there's some crossover and convergent evolution, but different fields do things differently. Every "key aspect of science" in popular culture isn't actually necessary:

- Peer review? Some fields progress mainly from arXiv and blog posts on github. (What does the "peer" in "peer review" mean, anyway? If my blog posts get reviewed by my peers before posting, are they peer-reviewed?)

- Universities? Is research at Max Planck Institutes not real science?

- Degrees? Was Michael Faraday not a real scientist?

Back in 1920 a NYT editorial said rockets were logically impossible, and I've seen that referenced by people saying "nobody really knows what will work, so you just have to experiment randomly". But engineers actually did understand Newton's laws of motion in 1920; that's just an example of the NYT having no competence in science or engineering.

concept overbundling

People bundle concepts together to simplify thinking. That's inevitable, but when someone cares greatly about a complex issue, they should put some effort into understanding its components.

When people don't do this, it's tempting to call it "lack of curiosity" or "stupidity", but consider the sources people read. People look to experts for how and when they should break down concepts. If you look at, say, bike enthusiasts, they often have strong opinions about details of gear reducers or drive systems or tire styles. Meanwhile, "nutrition enthusiasts" are often focused on one particular thing that doesn't even matter that much, despite (I hope I'm not offending the bike people) nutrition being more complex than bicycles. I think this is a result of the content of information sources about bikes vs nutrition, which in turn is a result of incentives and network effects.

my view

gradient descent

I don't think of science or culture as progressing through a tree of nodes. Rather, I think of the evolution of them over time as being like unstable gradient descent on a high-dimensional energy landscape, which is similar enough to training of a large neural network to have some similar properties. I've made that analogy previously.

tech selection

My view is that potential technology is neutral on average, but developed and implemented technology tends to be somewhat good on average. That is, I think tech is only good because of the choices made about it.

Researchers, regulators, companies, and individuals all have different information and incentives regarding new technology. In that kind of situation, I think everyone should do a little bit. Meaning, a bit of researchers choosing their topics, a bit of regulation, and a bit of individuals choosing how to use the things developed.

Different people will advocate for more or less influence of particular levels, and there's an equilibrium, a balance of power between people with tendencies towards different views. Some people strongly want researchers and regulators to be less selective, but I don't think even libertarian techno-optimists would be happy about me blogging about bioweapon design.

Wirth's Law

You work three jobs? Uniquely American, isn't it? I mean, that is fantastic that you're doing that.

— President Bush in 2005, speaking to a divorced mother of three

It's been widely said that software expands to consume the available resources. Computers get faster, and software gets slower...up to the point where it starts actually causing problems. Large companies release video games or use websites that have performance slow enough to cause major problems. The existence of such failure is the force pushing institutions towards competence, and without that, they get worse over time until failure starts happening.

A century ago, it was predicted that by now, people would be working under 20 hours a week. Apologist economists will sometimes say things like, "But now you want a computer and Netflix" but you can have both for $30 a month. What about the rest of those extra work hours? Better-quality housing? People living in 60-year-old houses aren't paying dramatically less rent.

It's true that productivity at farms and factories has improved massively. Computers should theoretically be a comparable improvement to office work. Where has that extra productivity gone? It's gone to time spent in meetings and classes and bullshit jobs that are, from a global perspective, useless. (Also, to luxuries for the ultra-wealthy, and supporting the people providing those luxuries.) I could post more things than I do, but...what's the point of more technology if it just gives institutions more room to be corrupt?

DDT

I love DDT, it’s so good.

Quite the title on that article there. More competition is fine and all, but "American Vulcan"? Big words for making a company with designs worse than Northrop's and DFM worse than China's. Kratos Defense seems more competent, but somehow Anduril has a much higher valuation; I guess that's the power of influential VCs.

DDT is bad, actually

I didn't expect, in the year 2024, to have a need to argue about DDT. But here I am. I guess I can talk about some heuristics for molecular toxicology.

When you have aromatics with halogens on them, they're relatively likely to be endocrine disruptors. And indeed, the problem DDT is best known for is it being an endocrine disruptor. PBDEs are bad for the same reason.

When you have aromatics without any hydrophilic groups on them, they might be oxidized to epoxides by p450 oxidases. That's why benzene is toxic: it's oxidized to benzene oxide in an interesting reaction. And indeed, DDT is metabolized by p450s to products including epoxides. So, we should expect DDT to be bad in similar ways to benzene - that is, genotoxic and carcinogenic.

Compounds designed to kill a certain kind of organism are more likely to harm similar organisms. DDT was designed to kill mosquitos, so it might be bad for other insects. And indeed, it kills bees pretty effectively, as do many insecticides.

When you have a molecule like DDT without any of the functional groups that make enzymatic processing easier, it tends to be metabolized slowly. When you have a slowly-metabolized molecule that's hydrophobic with moderate aprotic polarity, it tends to build up in fats, and then biomagnification happens as predators eat prey. And indeed, DDT has biomagnification, and levels got high enough in birds and larger fish to be a real problem.

Of course, that only covers half the argument about DDT. Advocates for it say, "DDT isn't bad, but even if it is, it still saves lives, so bans on it mean more deaths". But that's wrong too.

There is no global ban on DDT; a few countries are still using it, notably India. The biggest use of DDT was for agriculture, and even if malaria is the only thing you care about, you shouldn't want DDT used on crops. Insects can and have evolved resistance to DDT, and reduced use of it on crops delayed resistance to it in mosquitoes.

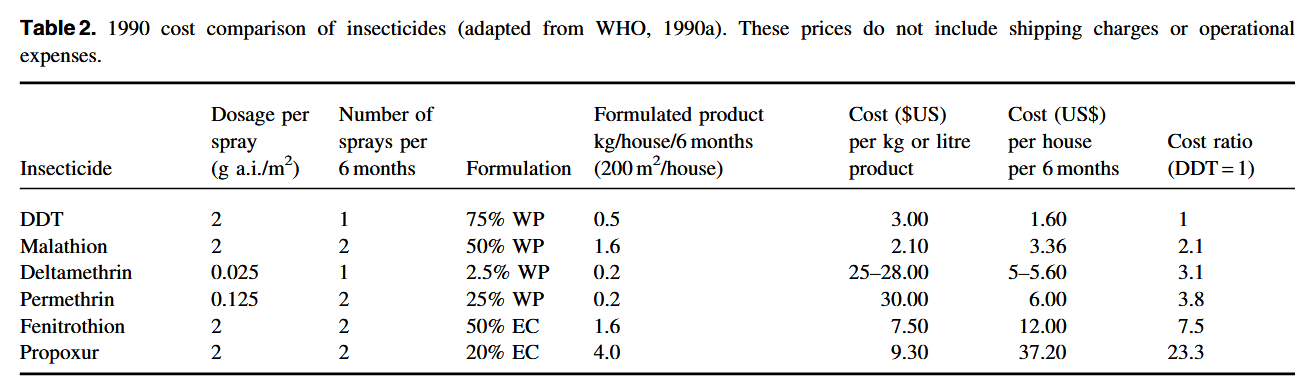

People decided DDT isn't worthwhile largely because pyrethroids are a better option; they basically do the same thing to insects but with more specificity. The only advantage DDT has over those is lower production cost, but the environmental harms per kg of DDT are greater than the production cost savings, so using it is just never a good tradeoff.

Well, the above is just a half-assed side-note of this post covering what I already knew; I could certainly be more thorough. Since Palmer is still so proud of his debate-club arguments for DDT, I'd be happy to provide another chance to show them off by publicly debating him.

circular reasoning

When someone like Palmer does something like advocate for DDT, what's the mindset involved? I think it's basically circular logic:

- DDT is good because the only people arguing against it are environmentalists, and environmentalists are dumb

- if someone is arguing against something good like DDT they must be an environmentalist

- environmentalists are dumb because they argue against good things like DDT

Even when each point is correct (which they aren't here) you're obviously supposed to compensate for that kind of looping feedback, but some people don't.

anti-democratic tendencies

For the sake of progress, some people want to force everyone to deal with sonic booms, and Palmer wants to force those silly environmentalists to put up with some chemicals they dislike. "Progress", in the mind of Palmer Luckey, being a return to mass production of a particularly toxic chemical that was replaced decades ago by more-complex but superior alternatives. Sigh. I'm talking about a billionaire here yet I feel like I'm shooting fish in a barrel; I guess that's what happens when I'm used to fans of LoGH or Planetes and I'm talking about a fan of Yugioh and SAO.

Government regulations and agencies have a lot of problems and poor decisions. I'm sympathetic to calls for changing them, but I've lost track of how many times I've seen an article by some pundit or economist or CEO saying "This government agency is flawed...and that's why we need to override it to do [something extremely stupid]." I've seen people extremely mad about things such as:

- the FDA not approving Ivermectin for COVID

- the FDA not banning aluminum cookware

- the FTC prosecuting actual monopolies

- the FDA banning BPA in drink containers

- the NRC not allowing TerraPower's unsafe design

- people trying to ban leaded aviation gasoline

As bad as things are in government regulatory agencies these days, on average, the suggestions for changes I've seen in magazine/newspaper articles have generally been worse. But some people take it to the next level by saying that their favorite stupid idea not being implemented means democracy is a failure. To them I'd say, "If democracy is failing, it's because of people like you."

learn some humility

Harm comes to those who know only victory and do not know defeat.

— Tokugawa Ieyasu

I like that quote, but many powerful people don't seem to understand its meaning. Some people succeed because of luck or their family, and the conclusion they make is that they're always right. Some people believe in X, then X happens to be true for their case, and the conclusion they make is that X is always true.

And this prediction was basically correct, but missed the fact that it's more efficient to work 30-40 hours per week while working and then take weeks or decades off when not working.

The extra time has gone to more leisure, less child labor, more schooling, and earlier retirement (plus support for people who can't work at all).