Seems like the easiest way to satisfy that definition would be to:

- Set up a network and dataset with at least one local minimum which is not a global minimum

- ... Then add an intermediate layer which estimates the gradient, and doesn't connect to the output at all.

This feels like cheating to me, but I guess I wasn't super precise with 'feedforward neural network'. I meant 'fully connected neural network', so the gradient computation has to be connected by parameters to the outputs. Specifically, I require that you can write the network as

where the weight matrices are some nice function of (where we need a weight sharing function to make the dimensions work out. The weight sharing function takes in and produces the matrices that are actually used in the forward pass.)

I guess I should be more precise about what 'nice means', to rule out weight sharing functions that always zero out input, but it turns out this is kind of tricky. Let's require the weight sharing function to be differentiable and have image that satisfies for any projection. (A weaker condition is if the weight sharing function can only duplicate parameters).

This is a plausible internal computation that the network could be doing, but the problem is that the gradients flow back through from the output to the computation of the gradient to the true value y, and so GD will use that to set the output to be the appropriate true value.

Following up to clarify this: the point is that this attempt fails 2a because if you perturb the weights along the connection , there is now a connection from the internal representation of to the output, and so training will send this thing to the function .

I'm a bit confused as to why this would work.

If the circuit in the intermediate layer that estimates the gradient does not influence the output, wouldn't they just be free parameters that can be varied with no consequence to the loss? If so, this violates 2a since perturbing these parameters would not get the model to converge to the desired solution.

This is very interesting and I'll have a crack. I have an intuition that two restrictions are too strong, and a proof in either direction will exploit them without telling you much about real gradient hackers:

- Having to take your weights as inputs:

If I understand this correctly the weight restrictions needed mean actually lives on a d dimensional subspace of . My intuition is that in real life the scenarios we expect gradient hackers to get clues to their parameters but not necessarily a full summary.

In a reality maybe the information would be clues that the model can gleam from it's own behaviour about how it's being changed. Perhaps this is some low dimensional summary of it's functional behaviour on a variety of inputs? - Having to move toward a single point :

I think the phenomena should not be viewed in parameter space, but function space although I do anticipate that makes this problem harder.

Instead of expecting the gradient hacker to move toward the single point , it is more appropriate to expect it to move towards the set of parameters that correspond to the same function (if such redundancy exists).

Secondly, I'm unsure but If the model is exhibiting gradient hacking behaviour, does that necessarily mean it tends toward a single point in function space. Perhaps the selections pressures would focus on some capabilities (such as the capacity to gradient hack) and not preserve others.

Epistemics: Off the cuff. Second point about preserving capabilities seems broadly correct but a bit too wide for what you're aiming to actually achieve here.

My troll example is a fully connected network with all zero weights and biases, no skip connections.

This isn't something that you'd reach in regular training, since networks are initialized away from zero to avoid this. But it does exhibit a basic ingredient in controlling the gradient flow.

To look for a true hacker I'd try to reconfigure the way the downstream computation works (by modifying attention weights, saturating relus, or similar) based on some model of the inputs, in a way that pushes around where the gradients go.

At least under most datasets, it seems to me like the zero NN fails condition 2a, as perturbing the weights will not cause it to go back to zero.

This is a relatively clean subproblem that we came upon a few months ago while thinking about gradient hacking. We're throwing it out to the world to see if anyone can make progress.

Problem: Construct a gradient hacker (definition below), or prove that one cannot exist under the given conditions.

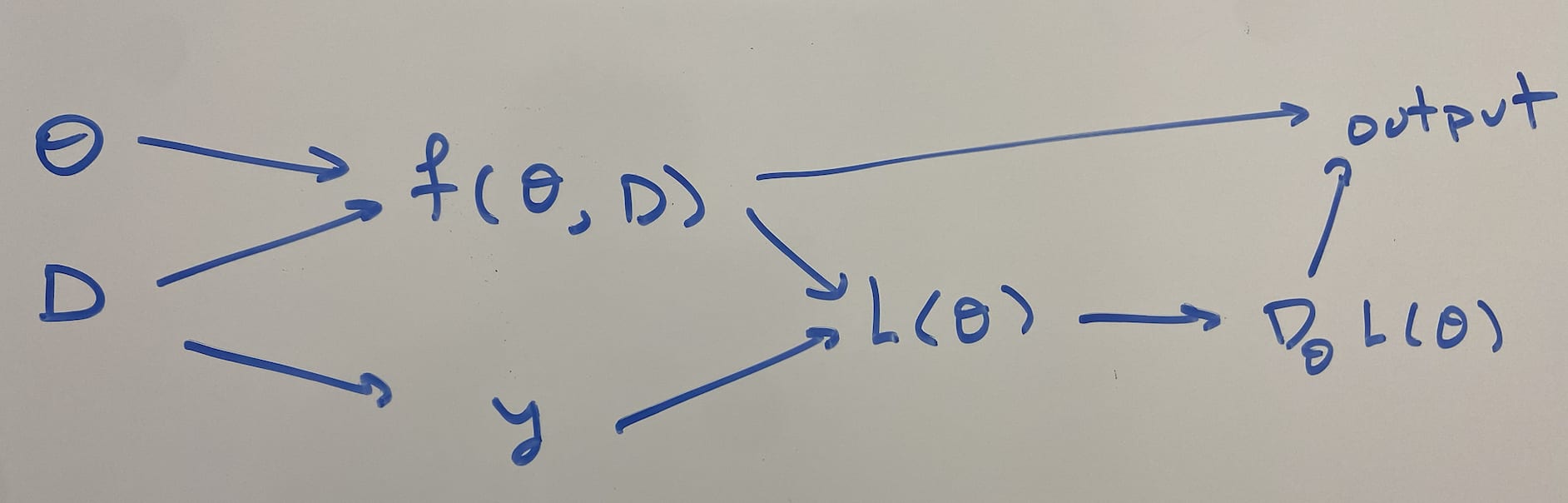

Setup: Let x∈Rd be the network inputs, θ∈Rw, be the network trainable parameters, ^y∈R be the network outputs, and f(x,θ)=^y be the network architecture. f(x,θ) must be a feedforward neural network that reads in its own weights as input. Weight sharing is allowed (vertical or horizontal), and some weight sharing is necessary in order to take all w weights as input.

Suppose that we train this network on a dataset D={x(i),y(i)}, with MSE loss L(θ)=1n∑i(f(x(i),θ)−y(i))2, assuming gradient flows: θ′(t)=−∇θL(θ(t)). Given an initial point θ0, the training dynamics are therefore:

θ(t)=θ0−∫t0∇θL(θ(x))dxDefinition: A tuple (f,θg,D) is a gradient hacker if the following conditions hold:

This captures my intuition that a gradient hacker knows where it wants to go (in this case "get to θg"), and then it should decide what it outputs in order to make the gradient true.

Some more ambitious problems (if gradient hackers exist):

This is a bit strict, but we didn't want to list different ways something could be isomorphic to the gradient.