it's surprising just how much of cutting edge research (at least in ML) is dealing with really annoying and stupid bottlenecks. pesky details that seem like they shouldn't need attention. tools that in a good and just world would simply not break all the time.

i used to assume this was merely because i was inexperienced, and that surely eventually you learn to fix all the stupid problems, and then afterwards you can just spend all your time doing actual real research without constantly needing to context switch to fix stupid things.

however, i've started to think that as long as you're pushing yourself to do novel, cutting edge research (as opposed to carving out a niche and churning out formulaic papers), you will always spend most of your time fixing random stupid things. as you get more experienced, you get bigger things done faster, but the amount of stupidity is conserved. as they say in running- it doesn't get easier, you just get faster.

as a beginner, you might spend a large part of your research time trying to install CUDA or fighting with python threading. as an experienced researcher, you might spend that time instead diving deep into some complicated distributed trai...

Not only is this true in AI research, it’s true in all science and engineering research. You’re always up against the edge of technology, or it’s not research. And at the edge, you have to use lots of stuff just behind the edge. And one characteristic of stuff just behind the edge is that it doesn’t work without fiddling. And you have to build lots of tools that have little original content, but are needed to manipulate the thing you’re trying to build.

After decades of experience, I would say: any sensible researcher spends a substantial fraction of time trying to get stuff to work, or building prerequisites.

This is for engineering and science research. Maybe you’re doing mathematical or philosophical research; I don’t know what those are like.

a corollary is i think even once AI can automate the "google for the error and whack it until it works" loop, this is probably still quite far off from being able to fully automate frontier ML research, though it certainly will make research more pleasant

in research, if you settle into a particular niche you can churn out papers much faster, because you can develop a very streamlined process for that particular kind of paper. you have the advantage of already working baseline code, context on the field, and a knowledge of the easiest way to get enough results to have an acceptable paper.

while these efficiency benefits of staying in a certain niche are certainly real, I think a lot of people end up in this position because of academic incentives - if your career depends on publishing lots of papers, then a recipe to get lots of easy papers with low risk is great. it's also great for the careers of your students, because if you hand down your streamlined process, then they can get a phd faster and more reliably.

however, I claim that this also reduces scientific value, and especially the probability of a really big breakthrough. big scientific advances require people to do risky bets that might not work out, and often the work doesn't look quite like anything anyone has done before.

as you get closer to the frontier of things that have ever been done, the road gets tougher and tougher. you end up spending more time building basic infra...

the modern world has many flaws, but I'm still deeply grateful for the modern era of unprecedented peace, prosperity, and freedom in the developed world. 99% of people reading these words have never had to worry about dying in a cholera epidemic, or malaria or smallpox or the plague, or childbirth, or in war, or from a famine, or due to a political purge. this is not true for other times in history, or other places in the world today.

(extremely unoriginal thought, but still important to acknowledge periodically because it's easy to take for granted. especially because it's much more common to complain about ways the world is broken than to acknowledge what has improved over time.)

I decided to conduct an experiment at neurips this year: I randomly surveyed people walking around in the conference hall to ask whether they had heard of AGI

I found that out of 38 respondents, only 24 could tell me what AGI stands for (63%)

we live in a bubble

the specific thing i said to people was something like:

excuse me, can i ask you a question to help settle a bet? do you know what AGI stands for? [if they say yes] what does it stand for? [...] cool thanks for your time

i was careful not to say "what does AGI mean".

most people who didn't know just said "no" and didn't try to guess. a few said something like "artificial generative intelligence". one said "amazon general intelligence" (??). the people who answered incorrectly were obviously guessing / didn't seem very confident in the answer.

if they seemed confused by the question, i would often repeat and say something like "the acronym AGI" or something.

several people said yes but then started walking away the moment i asked what it stood for. this was kind of confusing and i didn't count those people.

when i was new to research, i wouldn't feel motivated to run any experiment that wouldn't make it into the paper. surely it's much more efficient to only run the experiments that people want to see in the paper, right?

now that i'm more experienced, i mostly think of experiments as something i do to convince myself that a claim is correct. once i get to that point, actually getting the final figures for the paper is the easy part. the hard part is finding something unobvious but true. with this mental frame, it feels very reasonable to run 20 experiments for every experiment that makes it into the paper.

it's quite plausible (40% if I had to make up a number, but I stress this is completely made up) that someday there will be an AI winter or other slowdown, and the general vibe will snap from "AGI in 3 years" to "AGI in 50 years". when this happens it will become deeply unfashionable to continue believing that AGI is probably happening soonish (10-15 years), in the same way that suggesting that there might be a winter/slowdown is unfashionable today. however, I believe in these timelines roughly because I expect the road to AGI to involve both fast periods and slow bumpy periods. so unless there is some super surprising new evidence, I will probably only update moderately on timelines if/when this winter happens

also a lot of people will suggest that alignment people are discredited because they all believed AGI was 3 years away, because surely that's the only possible thing an alignment person could have believed. I plan on pointing to this and other statements similar in vibe that I've made over the past year or two as direct counter evidence against that

(I do think a lot of people will rightly lose credibility for having very short timelines, but I think this includes a big mix of capabilities and alignment people, and I think they will probably lose more credibility than is justified because the rest of the world will overupdate on the winter)

every 4 years, the US has the opportunity to completely pivot its entire policy stance on a dime. this is more politically costly to do if you're a long-lasting autocratic leader, because it is embarrassing to contradict your previous policies. I wonder how much of a competitive advantage this is.

Autarchies, including China, seem more likely to reconfigure their entire economic and social systems overnight than democracies like the US, so this seems false.

I mean, the proximate cause of the 1989 protests was the death of the quite reformist general secretary Hu Yaobang. The new general secretary, Zhao Ziyang, was very sympathetic towards the protesters and wanted to negotiate with them, but then he lost a power struggle against Li Peng and Deng Xiaoping (who was in semi retirement but still held onto control of the military). Immediately afterwards, he was removed as general secretary and martial law was declared, leading to the massacre.

people around these parts often take their salary and divide it by their working hours to figure out how much to value their time. but I think this actually doesn't make that much sense (at least for research work), and often leads to bad decision making.

time is extremely non fungible; some time is a lot more valuable than other time. further, the relation of amount of time worked to amount earned/value produced is extremely nonlinear (sharp diminishing returns). a lot of value is produced in short flashes of insight that you can't just get more of by spending more time trying to get insight (but rather require other inputs like life experience/good conversations/mentorship/happiness). resting or having fun can help improve your mental health, which is especially important for positive tail outcomes.

given that the assumptions of fungibility and linearity are extremely violated, I think it makes about as much sense as dividing salary by number of keystrokes or number of slack messages.

concretely, one might forgo doing something fun because it seems like the opportunity cost is very high, but actually diminishing returns means one more hour on the margin is much less valuable than the average implies, and having fun improves productivity in ways not accounted for when just considering the intrinsic value one places on fun.

but actually diminishing returns means one more hour on the margin is much less valuable than the average implies

This importantly also goes in the other direction!

One dynamic I have noticed people often don't understand is that in a competitive market (especially in winner-takes-all-like situations) the marginal returns to focusing more on a single thing can be sharply increasing, not only decreasing.

In early-stage startups, having two people work 60 hours is almost always much more valuable than having three people work 40 hours. The costs of growing a team are very large, the costs of coordination go up very quickly, and so if you are at the core of an organization, whether you work 40 hours or 60 hours is the difference between being net-positive vs. being net-negative.

This is importantly quite orthogonal whether you should rest or have fun or whatever. While there might be at an aggregate level increasing marginal returns to more focus, it is also the case that in such leadership positions, the most important hours are much much more productive than the median hour, and so figuring out ways to get more of the most important hours (which often rely on peak cognitive performance and a non-conflicted motivational system) is even more leveraged than adding the marginal hour (but I think it's important to recognize both effects).

agree it goes in both directions. time when you hold critical context is worth more than time when you don't. it's probably at least sometimes a good strategy to alternate between working much more than sustainable and then recovering.

my main point is this is a very different style of reasoning than what people usually do when they talk about how much their time is worth.

random half baked thoughts from a sleep deprived jet lagged mind: my guess is that the few largest principal components of variance of human intelligence are something like:

- a general factor that affects all cognitive abilities uniformly (this is a sum of a bazillion things. they could be something physiological like better cardiovascular function, or more efficient mitochondria or something; or maybe there's some pretty general learning/architecture hyperparameter akin to lr or aspect ratio that simply has better or worse configurations. each small change helps/hurts a little bit). having a better general factor makes you better at pattern recognition and prediction, which is the foundation of all intelligence. whether this is learning a policy or a world model, you need to be able to spot regularities in the world to exploit to have any hope of making good predictions.may

- a systematization factor (how much to be inclined towards using the machinery of pattern recognition towards finding and operating using explicit rules about the world, vs using that machinery implicitly and relying on intuition). this is the autist vs normie axis. importantly, it's not like normies are born with

why is ADHD also strongly correlated with systematization? it could just be worse self modelling - ADHD happens when your brain's model of its own priorities and motivations falls out of sync from your brain's actual priorities and motivations. if you're bad at understanding yourself, you will misunderstand your priorities, and also you will not be able to control your priorities, because you won't know what kinds of evidence will really persuade your brain to adopt a specific priority, and your brain will learn that it can't really trust you to assign it priorities to satisfy its motives (burnout).

why do stimulants help ADHD? well, they short circuit the part where your brain figures out what priorities to trust based on whether they achieve your true motives. if your brain has already learned that your self model is bad at picking actions that eventually pay off towards its true motives, it won't put its full effort behind those actions. if you can trick it by making every action feel like it's paying off, you can get it to go along.

honestly unclear whether this is good or bad. on the one hand, if your self model has fallen out of sync, this is pretty necessary to get things done, and could get you out of a bad feedback loop (ADHD is really bad for noticing that your self model has fallen horribly out of sync and acting effectively on it!). some would argue on naturalistic grounds that ideally the true long term solution is to use your brain's machinery the way it was always intended, by deeply understanding and accepting (and possibly modifying) your actual motives/priorities and having them steer your actions. the other option is to permanently circumvent your motivation system, to turn it into a rubber stamp for whatever decrees are handed down from the self model, which, forever unmoored from needing to model the self, is no longer an understanding of the self but rather an aspirational endpoint towards which the self is molded. I genuinely don't know which is better as an end goal.

execution is necessary for success, but direction is what sets apart merely impressive and truly great accomplishment. though being better at execution can make you better at direction, because it enables you to work on directions that others discard as impossible.

timelines takes

- i've become more skeptical of rsi over time. here's my current best guess at what happens as we automate ai research.

- for the next several years, ai will provide a bigger and bigger efficiency multiplier to the workflow of a human ai researcher.

- ai assistants will probably not uniformly make researchers faster across the board, but rather make certain kinds of things way faster and other kinds of things only a little bit faster.

- in fact probably it will make some things 100x faster, a lot of things 2x faster, and then be literally useless for a lot of remaining things

- amdahl's law tells us that we will mostly be bottlenecked on the things that don't get sped up a ton. like if the thing that got sped up 100x was only 10% of the original thing, then you don't get more than a 1/(1 - 10%) speedup.

- i think the speedup is a bit more than amdahl's law implies. task X took up 10% of the time because there is diminishing returns to doing more X, and so you'd ideally do exactly the amount of X such that the marginal value of time spent on X is exactly in equilibrium with time spent on anything else. if you suddenly decrease the cost of X substantially, the equilibrium point shifts

- for the next several years, ai will provide a bigger and bigger efficiency multiplier to the workflow of a human ai researcher.

My current best guess median is that we'll see 6 OOMs of effective compute in the first year after full automation of AI R&D if this occurs in ~2029 using a 1e29 training run and compute is scaled up by a factor of 3.5x[1] over the course of this year[2]. This is around 5 years of progress at the current rate[3].

How big of a deal is 6 OOMs? I think it's a pretty big deal; I have a draft post discussing how much an OOM gets you (on top of full automation of AI R&D) that I should put out somewhat soon.

Further, my distribution over this is radically uncertain with a 25th percentile of 2.5 OOMs (2 years of progress) and a 75th percentile of 12 OOMs.

The short breakdown of the key claims is:

- Initial progress will be fast, perhaps ~15x faster algorithmic progress than humans.

- Progress will probably speed up before slowing down due to training smarter AIs that can accelerate progress even faster, and this being faster than returns diminish on software.

- We'll be quite far from the limits of software progress (perhaps median 12 OOMs) at the point when we first achieve full automation.

Here is a somewhat summarized and rough version of the argument (stealing heavily from some of Tom...

libraries abstract away the low level implementation details; you tell them what you want to get done and they make sure it happens. frameworks are the other way around. they abstract away the high level details; as long as you implement the low level details you're responsible for, you can assume the entire system works as intended.

a similar divide exists in human organizations and with managing up vs down. with managing up, you abstract away the details of your work and promise to solve some specific problem. with managing down, you abstract away the mission and promise that if a specific problem is solved, it will make progress towards the mission.

(of course, it's always best when everyone has state on everything. this is one reason why small teams are great. but if you have dozens of people, there is no way for everyone to have all the state, and so you have to do a lot of abstracting.)

when either abstraction leaks, it causes organizational problems -- micromanagement, or loss of trust in leadership.

there are a lot of video games (and to a lesser extent movies, books, etc) that give the player an escapist fantasy of being hypercompetent. It's certainly an alluring promise: with only a few dozen hours of practice, you too could become a world class fighter or hacker or musician! But because becoming hypercompetent at anything is a lot of work, the game has to put its finger on the scale to deliver on this promise. Maybe flatter the user a bit, or let the player do cool things without the skill you'd actually need in real life.

It's easy to dismiss this kind of media as inaccurate escapism that distorts people's views of how complex these endeavors of skill really are. But it's actually a shockingly accurate simulation of what it feels like to actually be really good at something. As they say, being competent doesn't feel like being competent, it feels like the thing just being really easy.

reliability is surprisingly important. if I have a software tool that is 90% reliable, it's actually not that useful for automation, because I will spend way too much time manually fixing problems. this is especially a problem if I'm chaining multiple tools together in a script. I've been bit really hard by this because 90% feels pretty good if you run it a handful of times by hand, but then once you add it to your automated sweep or whatever it breaks and then you have to go in and manually fix things. and getting to 99% or 99.9% is really hard because things break in all sorts of weird ways.

I think this has lessons for AI - lack of reliability is one big reason I fail to get very much value out of AI tools. if my chatbot catastrophically hallucinates once every 10 queries, then I basically have to look up everything anyways to check. I think this is a major reason why cool demos often don't mean things that are practically useful - 90% reliable it's great for a demo (and also you can pick tasks that your AI is more reliable at, rather than tasks which are actually useful in practice). this is an informing factor for why my timelines are longer than some other people's

One nuance here is that a software tool that succeeds at its goal 90% of the time, and fails in an automatically detectable fashion the other 10% of the time is pretty useful for partial automation. Concretely, if you have a web scraper which performs a series of scripted clicks in hardcoded locations after hardcoded delays, and then extracts a value from the page from immediately after some known hardcoded text, that will frequently give you a ≥ 90% success rate of getting the piece of information you want while being much faster to code up than some real logic (especially if the site does anti-scraper stuff like randomizing css classes and DOM structure) and saving a bunch of work over doing it manually (because now you only have to manually extract info from the pages that your scraper failed to scrape).

even if scaling does eventually solve the reliability problem, it means that very plausibly people are overestimating how far along capabilities are, and how fast the rate of progress is, because the most impressive thing that can be done with 90% reliability plausibly advances faster than the most impressive thing that can be done with 99.9% reliability

i've noticed a life hyperparameter that affects learning quite substantially. i'd summarize it as "willingness to gloss over things that you're confused about when learning something". as an example, suppose you're modifying some code and it seems to work but also you see a warning from an unrelated part of the code that you didn't expect. you could either try to understand exactly why it happened, or just sort of ignore it.

reasons to set it low:

- each time your world model is confused, that's an opportunity to get a little bit of signal to improve your world model. if you ignore these signals you increase the length of your feedback loop, and make it take longer to recover from incorrect models of the world.

- in some domains, it's very common for unexpected results to actually be a hint at a much bigger problem. for example, many bugs in ML experiments cause results that are only slightly weird, but if you tug on the thread of understanding why your results are slightly weird, this can cause lots of your experiments to unravel. and doing so earlier rather than later can save a huge amount of time

- understanding things at least one level of abstraction down often lets you do things more

don't worry too much about doing things right the first time. if the results are very promising, the cost of having to redo it won't hurt nearly as much as you think it will. but if you put it off because you don't know exactly how to do it right, then you might never get around to it.

in some way, bureaucracy design is the exact opposite of machine learning. while the goal of machine learning is to make clusters of computers that can think like humans, the goal of bureaucracy design is to make clusters of humans that can think like a computer

my referral/vouching policy is i try my best to completely decouple my estimate of technical competence from how close a friend someone is. i have very good friends i would not write referrals for and i have written referrals for people i basically only know in a professional context. if i feel like it's impossible for me to disentangle, i will defer to someone i trust and have them make the decision. this leads to some awkward conversations, but if someone doesn't want to be friends with me because it won't lead to a referral, i don't want to be friends with them either.

Strong agree (except in that liking someone's company is evidence that they would be a pleasant co-worker, but that's generally not a high order bit). I find it very annoying that standard reference culture seems to often imply giving extremely positive references unless someone was truly awful, since it makes it much harder to get real info from references

learning thread for taking notes on things as i learn them (in public so hopefully other people can get value out of it)

VAEs:

a normal autoencoder decodes single latents z to single images (or whatever other kind of data) x, and also encodes single images x to single latents z.

with VAEs, we want our decoder (p(x|z)) to take single latents z and output a distribution over x's. for simplicity we generally declare that this distribution is a gaussian with identity covariance, and we have our decoder output a single x value that is the mean of the gaussian.

because each x can be produced by multiple z's, to run this backwards you also need a distribution of z's for each single x. we call the ideal encoder p(z|x) - the thing that would perfectly invert our decoder p(x|z). unfortunately, we obviously don't have access to this thing. so we have to train an encoder network q(z|x) to approximate it. to make our encoder output a distribution, we have it output a mean vector and a stddev vector for a gaussian. at runtime we sample a random vector eps ~ N(0, 1) and multiply it by the mean and stddev vectors to get an N(mu, std).

to train this thing, we would like to optimize the following loss function:

-log p(x) + KL(q(z|x)||p(z|x))

where the terms optimize the likelihood (how good is the VAE at modelling dat...

a take I've expressed a bunch irl but haven't written up yet: feature sparsity might be fundamentally the wrong thing for disentangling superposition; circuit sparsity might be more correct to optimize for. in particular, circuit sparsity doesn't have problems with feature splitting/absorption

the most valuable part of a social event is often not the part that is ostensibly the most important, but rather the gaps between the main parts.

- at ML conferences, the headline keynotes and orals are usually the least useful part to go to; the random spontaneous hallway chats and dinners and afterparties are extremely valuable

- when doing an activity with friends, the activity itself is often of secondary importance. talking on the way to the activity, or in the gaps between doing the activity, carry a lot of the value

- at work, a lot of the best conversations happen outside of scheduled 1:1s and group meetings, but rather happen in spontaneous hallway or dinner groups

One of the directions im currently most excited about (modern control theory through algebraic analysis) I learned about while idly chitchatting with a colleague at lunch about old school cybernetics. We were both confused why it was such a big deal in the 50s and 60s then basically died.

A stranger at the table had overheard our conversation and immediately started ranting to us about the history of cybernetics and modern methods of control theory. Turns out that control theory has developed far beyond whay people did in the 60s but names, techniques, methods have changed and this guy was one of the world experts. I wouldn't have known to ask him because the guy's specialization on the face of it had nothing to do with control theory.

a lot of unconventional people choose intentionally to ignore normie-legible status systems. this can take the form of either expert consensus or some form of feedback from reality that is widely accepted. for example, many researchers especially around these parts just don't publish at all in normal ML conferences at all, opting instead to depart into their own status systems. or they don't care whether their techniques can be used to make very successful products, or make surprisingly accurate predictions etc. instead, they substitute some alternative status system, like approval of a specific subcommunity.

there's a grain of truth to this, which is that the normal status system is often messed up (academia has terrible terrible incentives). it is true that many people overoptimize the normal status system really hard and end up not producing very much value.

but the problem with starting your own status system (or choosing to compete in a less well-agreed-upon one) is that it's unclear to other people how much stock to put in your status points. it's too easy to create new status systems. the existing ones might be deeply flawed, but at least their difficulty is a known quantity.

o...

This comment seems to implicitly assume markers of status are the only way to judge quality of work. You can just, y'know, look at it? Even without doing a deep dive, the sort of papers or blog posts which present good research have a different style and rhythm to them than the crap. And it's totally reasonable to declare that one's audience is the people who know how to pick up on that sort of style.

The bigger reason we can't entirely escape "status"-ranking systems is that there's far too much work to look at it all, so people have to choose which information sources to pay attention to.

It's a question of resolution. Just looking at things for vibes is a pretty good way of filtering wheat from chaff, but you don't give scarce resources like jobs or grants to every grain of wheat that comes along. When I sit on a hiring committee, the discussions around the table are usually some mix of status markers and people having done the hard work of reading papers more or less carefully (this consuming time in greater-than-linear proportion to distance from your own fields of expertise). Usually (unless nepotism is involved) someone who has done that homework can wield more power than they otherwise would at that table, because people respect strong arguments and understand that status markers aren't everything.

Still, at the end of day, an Annals paper is an Annals paper. It's also true that to pass some of the early filters you either need (a) someone who speaks up strongly for you or (b) pass the status marker tests.

I am sometimes in a position these days of trying to bridge the academic status system and the Berkeley-centric AI safety status system, e.g. by arguing to a high status mathematician that someone with illegible (to them) status is actually approximately equiv...

I claim it is a lot more reasonable to use the reference class of "people claiming the end of the world" than "more powerful intelligences emerging and competing with less intelligent beings" when thinking about AI x-risk. further, we should not try to convince people to adopt the latter reference class - this sets off alarm bells, and rightly so (as I will argue in short order) - but rather to bite the bullet, start from the former reference class, and provide arguments and evidence for why this case is different from all the other cases.

this raises the question: how should you pick which reference class to use, in general? how do you prevent reference class tennis, where you argue back and forth about what is the right reference class to use? I claim the solution is you want to use reference classes that have consistently made good decisions irl. the point of reference classes is to provide a heuristic to quickly apply judgement to large swathes of situations that you don't have time to carefully examine. this is important because otherwise it's easy to get tied up by bad actors who avoid being refuted by making their beliefs very complex and therefore hard to argue against.

the b...

This all seems wrongheaded to me.

I endeavor to look at how things work and describe them accurately. Similarly to how I try to describe how a piece of code works, or how to to build a shed, I will try to accurately describe the consequences of large machine learning runs, which can include human extinction.

I personally think AGI will probably kill everyone. but this is a big claim and should be treated as such.

This isn't how I think about things. Reality is what exists, and if a claim accurately describes reality, then I should not want to hold it to higher standards than claims that do not describe reality. I don't think it's a good epistemology to rank claims by "bigness" and then say that the big ones are less likely and need more evidence. On the contrary, I think it's worth investing more in finding out if they're right, and generally worth bringing them up to consideration with less evidence than for "small" claims.

...on the other hand, everyone has personally experienced a dozen different doomsday predictions. whether that's your local church or faraway cult warning about Armageddon, or Y2K, or global financial collapse in 2008, or the maximally alarmist climate people, o

I think the group of people "claiming the end of the world" in the case of AI x-risk is importantly more credentialed and reasonable-looking than most prior claims about the end of the world. From the reference class and general heuristics perspective that you're talking about[1], I think how credible looking the people are is pretty important.

So, I think the reference class is more like claims of nuclear armageddon than cults. (Plausibly near maximally alarmist climate people are in a similar reference class.)

IDK how I feel about this perspective overall. ↩︎

It seems you are having in mind something like inference to the best explanation here. Bayesian updating, on the other hand, does need a prior distribution, and the question of which prior distribution to use cannot be waved away when there is a disagreement on how to update. In fact, that's one of the main problems of Bayesian updating, and the reason why it is often not used in arguments.

you might expect that the butterfly effect applies to ML training. make one small change early in training and it might cascade to change the training process in huge ways.

at least in non-RL training, this intuition seems to be basically wrong. you can do some pretty crazy things to the training process without really affecting macroscopic properties of the model (e.g loss). one very well known example is that using mixed precision training results in training curves that are basically identical to full precision training, even though you're throwing out a ton of bits of precision on every step.

people often say that limitations of an artistic medium breed creativity. part of this could be the fact that when it is costly to do things, the only things done will be higher effort

any time someone creates a lot of value without capturing it, a bunch of other people will end up capturing the value instead. this could be end consumers, but it could also be various middlemen. it happens not infrequently that someone decides not to capture the value they produce in the hopes that the end consumers get the benefit, but in fact the middlemen capture the value instead

saying "sorry, just to make sure I understand what you're saying, do you mean [...]" more often has been very valuable

hypothesis: intellectual progress mostly happens when bubbles of non tribalism can exist. this is hard to safeguard because tribalism is a powerful strategy, and therefore insulating these bubbles is hard. perhaps it is possible for there to exist a monopoly on tribalism to make non tribal intellectual progress happen, in the same way a monopoly on violence makes it possible to make economically valuable trade without fear of violence

theory: a large fraction of travel is because of mimetic desire (seeing other people travel and feeling fomo / keeping up with the joneses), signalling purposes (posting on IG, demonstrating socioeconomic status), or mental compartmentalization of leisure time (similar to how it's really bad for your office and bedroom to be the same room).

this explains why in every tourist destination there are a whole bunch of very popular tourist traps that are in no way actually unique/comparatively-advantaged to the particular destination. for example: shopping, amusement parks, certain kinds of museums.

a great way to get someone to dig into a position really hard (whether or not that position is correct) is to consistently misunderstand that position

almost every single major ideology has some strawman that the general population commonly imagines when they think of the ideology. a major source of cohesion within the ideology comes from a shared feeling of injustice from being misunderstood.

idea: flight insurance, where you pay a fixed amount for the assurance that you will definitely get to your destination on time. e.g if your flight gets delayed, they will pay for a ticket on the next flight from some other airline, or directly approach people on the next flight to buy a ticket off of them, or charter a private plane.

pure insurance for things you could afford to self insure is generally a scam (and the customer base of this product could probably afford to self insure) but this mostly provides value by handling the rather complicated logistics for you rather than by reducing the financial burden, and there are substantial benefits from economies of scale (e.g if you have enough customers you can maintain a fleet of private planes within a few hours of most major airports)

it's often stated that believing that you'll succeed actually causes you to be more likely to succeed. there are immediately obvious explanations for this - survivorship bias. obviously most people who win the lottery will have believed that buying lottery tickets is a good idea, but that doesn't mean we should take that advice. so we should consider the plausible mechanisms of action.

first, it is very common for people with latent ability to underestimate their latent ability. in situations where the cost of failure is low, it seems net positive to at least take seriously the hypothesis that you can do more than you think you can. (also keeping in mind that we often overestimate the cost of failure). there are also deleterious mental health effects to believing in a high probability of failure, and then bad mental health does actually cause failure - it's really hard to give something your all if you don't really believe in it.

belief in success also plays an important role in signalling. if you're trying to make some joint venture happen, you need to make people believe that the joint venture will actually succeed (opportunity costs exist). when assessing the likelihood of success...

my summary of these two papers: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1805.12152 https://arxiv.org/pdf/1905.02175

the first paper observes a phenomenon where adversarial accuracy and normal accuracy are at odds with each other. the authors present a toy example to explain this.

the construction involves giving each input one channel that is 90% accurate for predicting the binary label, and a bazillion iid gaussian channels that are as noisy as possible individually, so that when you take the average across all of them you get ~100% accuracy. they show that when you do -adversarial training on the input you learn to only use the 90% accurate feature, whereas normal training uses all bazillion weak channels.

the key to this construction is that they consider an -ball on the input (distance is the max across all coordinates). so this means by adding more and more features, you can move further and further in space (specifically, in terms of the number of features). but the distance between the means of the two high dimensional gaussians stays constant, so no matter what your is, at some point with enough channels you can pertur...

Is it a very universal experience to find it easier to write up your views if it's in response to someone else's writeup? Seems like the kind of thing that could explain a lot about how research tends to happen if it were a pretty universal experience.

there's an obvious synthesis of great man theory and broader structural forces theories of history.

there are great people, but these people are still bound by many constraints due to structural forces. political leaders can't just do whatever they want; they have to appease the keys of power within the country. in a democracy, the most obvious key of power is the citizens, who won't reelect a politician that tries to act against their interests. but even in dictatorships, keeping the economy at least kind of functional is important, because when the citizens are starving, they're more likely to revolt and overthrow the government. there are also powerful interest groups like the military and critical industries, which have substantial sway over government policy in both democracies and dictatorships. many powerful people are mostly custodians for the power of other people, in the same way that a bank is mostly a custodian for the money of its customers.

also, just because someone is involved in something important, it doesn't mean that they were maximally counterfactually responsible. structural forces often create possibilities to become extremely influential, but only in the direc...

one kind of reasoning in humans is a kind of instant intuition; you see something and something immediately and effortlessly pops into your mind. examples include recalling vocabulary in a language you're fluent in, playing a musical instrument proficiently, or having a first guess at what might be going wrong when debugging.

another kind of reasoning is the chain of thought, or explicit reasoning: you lay out your reasoning steps as words in your head, interspersed perhaps with visuals, or abstract concepts that you would have a hard time putting in words. It feels like you're consciously picking each step of the reasoning. Working through a hard math problem, or explicitly designing a codebase by listing the constraints and trying to satisfy them, are examples of this.

so far these map onto what people call system 1 and 2, but I've intentionally avoided these labels because I think there's actually a third kind of reasoning that doesn't fit well into either of these buckets.

sometimes, I need to put the relevant info into my head, and then just let it percolate slowly without consciously thinking about it. at some later time, insights into the problem will suddenly and unpredictably...

the possibility that a necessary ingredient in solving really hard problems is spending a bunch of time simply not doing any explicit reasoning

I have a pet theory that there are literally physiological events that take minutes, hours, or maybe even days or longer, to happen, which are basically required for some kinds of insight. This would look something like:

-

First you do a bunch of explicit work trying to solve the problem. This makes a bunch of progress, and also starts to trace out the boundaries of where you're confused / missing info / missing ideas.

-

You bash your head against that boundary even more.

- You make much less explicit progress.

- But, you also leave some sort of "physiological questions". I don't know the neuroscience at all, but to make up a story to illustrate what sort of thing I mean: One piece of your brain says "do I know how to do X?". Some other pieces say "maybe I can help". The seeker talks to the volunteers, and picks the best one or two. The seeker says "nah, that's not really what I'm looking for, you didn't address Y". And this plays out as some pattern of electrical signals which mean "this and this and this neuron shouldn't have been firing s

for people who are not very good at navigating social conventions, it is often easier to learn to be visibly weird than to learn to adapt to the social conventions.

this often works because there are some spaces where being visibly weird is tolerated, or even celebrated. in fact, from the perspective of an organization, it is good for your success if you are good at protecting weird people.

but from the perspective of an individual, leaning too hard into weirdness is possibly harmful. part of leaning into weirdness is intentional ignorance of normal conventions. this traps you in a local minimum where any progress on understanding normal conventions hurts your weirdness, but isn't enough to jump all the way to the basin of the normal mode of interaction.

(epistemic status: low confidence, just a hypothesis)

Since there are basically no alignment plans/directions that I think are very likely to succeed, and adding "of course, this will most likely not solve alignment and then we all die, but it's still worth trying" to every sentence is low information and also actively bad for motivation, I've basically recalibrated my enthusiasm to be centered around "does this at least try to solve a substantial part of the real problem as I see it". For me at least this is the most productive mindset for me to be in, but I'm slightly worried people might confuse this for me having a low P(doom), or being very confident in specific alignment directions, or so on, hence this post that I can point people to.

I think this may also be a useful emotional state for other people with similar P(doom) and who feel very demotivated by that, which impacts their productivity.

a common discussion pattern: person 1 claims X solves/is an angle of attack on problem P. person 2 is skeptical. there is also some subproblem Q (90% of the time not mentioned explicitly). person 1 is defending a claim like "X solves P conditional on Q already being solved (but Q is easy)", whereas person 2 thinks person 1 is defending "X solves P via solving Q", and person 2 also believes something like "subproblem Q is hard". the problem with this discussion pattern is it can lead to some very frustrating miscommunication:

- if the discussion recurses into whether Q is hard, person 1 can get frustrated because it feels like a diversion from the part they actually care about/have tried to find a solution for, which is how to find a solution to P given a solution to Q (again, usually Q is some implicit assumption that you might not even notice you have). it can feel like person 2 is nitpicking or coming up with fully general counterarguments for why X can never be solved.

- person 2 can get frustrated because it feels like the original proposed solution doesn't engage with the hard subproblem Q. person 2 believes that assuming Q were solved, then there would be many other proposals other than X that would also suffice to solve problem P, so that the core ideas of X actually aren't that important, and all the work is actually being done by assuming Q.

philosophy: while the claims "good things are good" and "bad things are bad" at first appear to be compatible with each other, actually we can construct a weird hypothetical involving exact clones that demonstrates that they are fundamentally inconsistent with each other

law: could there be ambiguity in "don't do things that are bad as determined by a reasonable person, unless the thing is actually good?" well, unfortunately, there is no way to know until it actually happens

One possible model of AI development is as follows: there exists some threshold beyond which capabilities are powerful enough to cause an x-risk, and such that we need alignment progress to be at the level needed to align that system before it comes into existence. I find it informative to think of this as a race where for capabilities the finish line is x-risk-capable AGI, and for alignment this is the ability to align x-risk-capable AGI. In this model, it is necessary but not sufficient for alignment for alignment to be ahead by the time it's at the finish line for good outcomes: if alignment doesn't make it there first, then we automatically lose, but even if it does, if alignment doesn't continue to improve proportional to capabilities, we might also fail at some later point. However, I think it's plausible we're not even on track for the necessary condition, so I'll focus on that within this post.

Given my distributions over how difficult AGI and alignment respectively are, and the amount of effort brought to bear on each of these problems, I think there's a worryingly large chance that we just won't have the alignment progress needed at the critical juncture.

I also think it's ...

i find it disappointing that a lot of people believe things about trading that are obviously crazy even if you only believe in a very weak form of the EMH. for example, technical analysis is obviously tea leaf reading - if it were predictive whatsoever, you could make a lot of money by exploiting it until it is no longer predictive.

Close friend of mine, a regular software engineer, recently threw tens of thousands of dollars - a sizable chunk of his yearly salary - at futures contracts on some absurd theory about the Japanese Yen. Over the last few weeks, he coinflipped his money into half a million dollars. Everyone who knows him was begging him to pull out and use the money to buy a house or something. But of course yesterday he sold his futures contracts and bought into 0DTE Nasdaq options on another theory, and literally lost everything he put in and then some. I'm not sure but I think he's down about half his yearly salary overall.

He has been doing this kind of thing for the last two years or so - not just making investments, but making the most absurd, high risk investments you can think of. Every time he comes up with a new trade, he has a story for me about how his cousin/whatever who's a commodities trader recommended the trade to him, or about how a geopolitical event is gonna spike the stock of Lockheed Martin, or something. On many occasions I have attempted to explain some kind of Inadequate Equilibria thesis to him, but it just doesn't seem to "stick".

It's not that he "rejects" the EMH in these ...

i think it's quite valuable to go through your key beliefs and work through what the implications would be if they were false. this has several benefits:

- picturing a possible world where your key belief is wrong makes it feel more tangible and so you become more emotionally prepared to accept it.

- if you ever do find out that the belief is wrong, you don't flinch away as strongly because it doesn't feel like you will be completely epistemically lost the moment you remove the Key Belief

- you will have more productive conversations with people who disagree with you on the Key Belief

- you might discover strategies that are robustly good whether or not the Key Belief is true

- you will become better at designing experiments to test whether the Key Belief is true

economic recession and subsequent reduction in speculative research, including towards AGI, seems very plausible

AI (by which I mean, like, big neural networks and whatever) is not that economically useful right now. furthermore, current usage figures are likely an overestimate of true economic usefulness because a very large fraction of it is likely to be bubbly spending that will itself dry up if there is a recession (legacy companies putting LLMs into things to be cool, startups that are burning money without PMF, consumers with disposable income to spend on entertainment).

it will probably still be profitable to develop AI tech, but things will be much more tethered to consumer usefulness.

this probably doesn't set AGI back that much but I think people are heavily underrating this as a possibility. it also probably heavily impacts the amount of alignment work done at labs.

one man's modus tollens is another man's modus ponens:

"making progress without empirical feedback loops is really hard, so we should get feedback loops where possible" "in some cases (i.e close to x-risk), building feedback loops is not possible, so we need to figure out how to make progress without empirical feedback loops. this is (part of) why alignment is hard"

A common cycle:

- This model is too oversimplified! Reality is more complex than this model suggests, making it less useful in practice. We should really be taking these into account. [optional: include jabs at outgroup]

- This model is too complex! It takes into account a bunch of unimportant things, making it much harder to use in practice. We should use this simplified model instead. [optional: include jabs at outgroup]

Sometimes this even results in better models over time.

the world is too big and confusing, so to get anything done (and to stay sane) you have to adopt a frame. each frame abstracts away a ton about the world, out of necessity. every frame is wrong, but some are useful. a frame comes with a set of beliefs about the world and a mechanism for updating those beliefs.

some frames contain within them the ability to become more correct without needing to discard the frame entirely; they are calibrated about and admit what they don't know. they change gradually as we learn more. other frames work empirically but are a...

for something to be a good way of learning, the following criteria have to be met:

- tight feedback loops

- transfer of knowledge to your ultimate goal

- sufficiently interesting that it doesn't feel like a grind

trying to do the thing you care about directly hits 2 but can fail 1 and 3. many things that you can study hit 1 but fail 2 and 3. and of course, many fun games hit 3 (and sometimes 1) but fail to hit 2.

lifehack: buying 3 cheap pocket sized battery packs costs like $60 and basically eliminates the problem of running out of phone charge on the go. it's much easier to remember to charge them because you can instantaneously exchange your empty battery pack for a full one when you realize you need one, plugging the empty battery pack happens exactly when you swap for a fresh one, and even if you forget once or lose one you have some slack

conference talks aren't worth going to irl because they're recorded anyways. ofc, you're not actually going to remember to watch the recording, but it's not like anyone pays attention at the irl talk anyways

a thriving culture is a mark of a healthy and intellectually productive community / information ecosystem. it's really hard to fake this. when people try, it usually comes off weird. for example, when people try to forcibly create internal company culture, it often comes off as very cringe.

there are two different modes of learning i've noticed.

- top down: first you learn to use something very complex and abstract. over time, you run into weird cases where things don't behave how you'd expect, or you feel like you're not able to apply the abstraction to new situations as well as you'd like. so you crack open the box and look at the innards and see a bunch of gears and smaller simpler boxes, and it suddenly becomes clear to you why some of those weird behaviors happened - clearly it was box X interacting with gear Y! satisfied, you use your newf

often the easiest way to gain status within some system is to achieve things outside that system

Corollary to Others are wrong != I am right (https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/4QemtxDFaGXyGSrGD/other-people-are-wrong-vs-i-am-right): It is far easier to convince me that I'm wrong than to convince me that you're right.

fun side project idea: create a matrix X and accompanying QR decomposition, such that X and Q are both valid QR codes that link to the wikipedia page about QR decomposition

current understanding of optimization

- high curvature directions (hessian eigenvectors with high eigenvalue) want small lrs. low curvature directions want big lrs

- if the lr in a direction is too small, it takes forever to converge. if the lr is too big, it diverges by oscillating with increasing amplitude

- momentum helps because if your lr is too small, it makes you move a bit faster. if your lr is too big, it causes the oscillations to cancel out with themselves. this makes high curvature directions more ok with larger lrs and low curvature directions more ok

Some aspirational personal epistemic rules for keeping discussions as truth seeking as possible (not at all novel whatsoever, I'm sure there exist 5 posts on every single one of these points that are more eloquent)

- If I am arguing for a position, I must be open to the possibility that my interlocutor may turn out to be correct. (This does not mean that I should expect to be correct exactly 50% of the time, but it does mean that if I feel like I'm never wrong in discussions then that's a warning sign: I'm either being epistemically unhealthy or I'm talking

hypothesis: the kind of reasoning that causes ML people to say "we have made no progress towards AGI whatsoever" is closely analogous to the kind of reasoning that makes alignment people say "we have made no progress towards hard alignment whatsoever"

ML people see stuff like GPT4 and correctly notice that it's in fact kind of dumb and bad at generalization in the same ways that ML always has been. they make an incorrect extrapolation, which is that AGI must therefore be 100 years away, rather than 10 years away

high p(doom) alignment people see current mode...

Understanding how an abstraction works under the hood is useful because it gives you intuitions for when it's likely to leak and what to do in those cases.

takes on takeoff (or: Why Aren't The Models Mesaoptimizer-y Yet)

here are some reasons we might care about discontinuities:

- alignment techniques that apply before the discontinuity may stop applying after / become much less effective

- makes it harder to do alignment research before the discontinuity that transfers to after the discontinuity (because there is something qualitatively different after the jump)

- second order effect: may result in false sense of security

- there may be less/negative time between a warning shot and the End

- harder to coordinate and slow do

The following things are not the same:

- Schemes for taking multiple unaligned AIs and trying to build an aligned system out of the whole

- I think this is just not possible.

- Schemes for taking aligned but less powerful AIs and leveraging them to align a more powerful AI (possibly with amplification involved)

- This breaks if there are cases where supervising is harder than generating, or if there is a discontinuity. I think it's plausible something like this could work but I'm not super convinced.

In the spirit of https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/fFY2HeC9i2Tx8FEnK/my-resentful-story-of-becoming-a-medical-miracle , some anecdotes about things I have tried, in the hopes that I can be someone else's "one guy on a message board. None of this is medical advice, etc.

- No noticeable effects from vitamin D (both with and without K2), even though I used to live somewhere where the sun barely shines and also I never went outside, so I was almost certainly deficient.

- I tried Selenium (200mg) twice and both times I felt like utter shit the next day.

- Glycine (2g) for

I wonder how many supposedly consistently successful retail traders are actually just picking up pennies in front of the steamroller, and would eventually lose it all if they kept at it long enough.

also I wonder how many people have runs of very good performance interspersed by big losses, such that the overall net gains are relatively modest, but psychologically they only remember/recount the runs of good performance, whereas the losses were just bad luck and will be avoided next time.

for a sufficiently competent policy, the fact that BoN doesn't update the policy doesn't mean it leaks any fewer bits of info to the policy than normal RL

aiming directly for achieving some goal is not always the most effective way of achieving that goal.

people love to find patterns in things. sometimes this manifests as mysticism- trying to find patterns where they don't exist, insisting that things are not coincidences when they totally just are. i think a weaker version of this kind of thinking shows up a lot in e.g literature too- events occur not because of the bubbling randomness of reality, but rather carry symbolic significance for the plot. things don't just randomly happen without deeper meaning.

some people are much more likely to think in this way than others. rationalists are very far along the...

One of the greatest tragedies of truth-seeking as a human is that the things we instinctively do when someone else is wrong are often the exact opposite of the thing that would actually convince the other person.

it is often claimed that merely passively absorbing information is not sufficient for learning, but rather some amount of intentional learning is needed. I think this is true in general. however, one interesting benefit of passively absorbing information is that you notice some concepts/terms/areas come up more often than others. this is useful because there's simply too much stuff out there to learn, and some knowledge is a lot more useful than other knowledge. noticing which kinds of things come up often is therefore useful for prioritization. I often notice that my motivational system really likes to use this heuristic for deciding how motivated to be while learning something.

a claim I've been saying irl for a while but have never gotten around to writing up: current LLMs are benign not because of the language modelling objective, but because of the generalization properties of current NNs (or to be more precise, the lack thereof). with better generalization LLMs are dangerous too. we can also notice that RL policies are benign in the same ways, which should not be the case if the objective was the core reason. one thing that can go wrong with this assumption is thinking about LLMs that are both extremely good at generalizing ...

Schmidhubering the agentic LLM stuff pretty hard https://leogao.dev/2020/08/17/Building-AGI-Using-Language-Models/

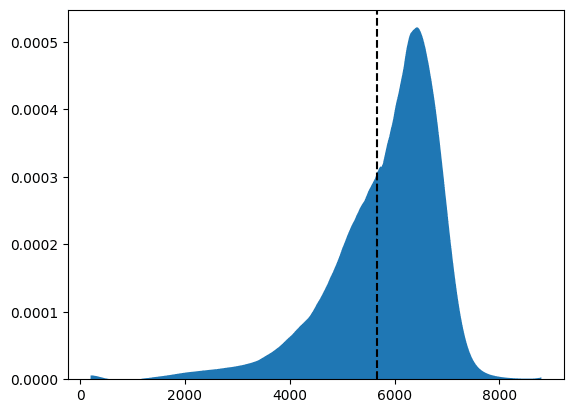

made an estimate of the distribution of prices of the SPX in one year by looking at SPX options prices, smoothing the implied volatilities and using Breeden-Litzenberger.

(not financial advice etc, just a fun side project)

twitter is great because it boils down saying funny things to purely a problem of optimizing for funniness, and letting twitter handle the logistics of discovery and distribution. being e.g a comedian is a lot more work.

the financial industry is a machine that lets you transmute a dollar into a reliable stream of ~4 cents a year ~forever (or vice versa). also, it gives you a risk knob you can turn that increases the expected value of the stream, but also the variance (or vice versa; you can take your risky stream and pay the financial industry to convert it into a reliable stream or lump sum)

in a highly competitive domain, it is often better and easier to be sui generis, rather than a top 10 percentile member of a large reference class

an interesting fact that I notice is that in domains where there are are a lot of objects in consideration, those objects have some structure so that they can be classified, and how often those objects occur follows a power law or something, there are two very different frames that get used to think about that domain:

- a bucket of atomic, structureless objects with unique properties where facts about one object don't really generalize at all to any other object

- a systematized, hierarchy or composition of properties or "periodic table" or full grid or objec

House rules for definitional disputes:

- If it ever becomes a point of dispute in an object level discussion what a word means, you should either use a commonly accepted definition, or taboo the term if the participants think those definitions are bad for the context of the current discussion. (If the conversation participants are comfortable with it, the new term can occupy the same namespace as the old tabooed term (i.e going forward, we all agree that the definition of X is Y for the purposes of this conversation, and all other definitions no longer appl

A few axes along which to classify optimizers:

- Competence: An optimizer is more competent if it achieves the objective more frequently on distribution

- Capabilities Robustness: An optimizer is more capabilities robust if it can handle a broader range of OOD world states (and thus possible pertubations) competently.

- Generality: An optimizer is more general if it can represent and achieve a broader range of different objectives

- Real-world objectives: whether the optimizer is capable of having objectives about things in the real world.

Some observations: it feels l...

A thought pattern that I've noticed myself and others falling into sometimes: Sometimes I will make arguments about things from first principles that look something like "I don't see any way X can be true, it clearly follows from [premises] that X is definitely false", even though there are people who believe X is true. When this happens, it's almost always unproductive to continue to argue on first principles, but rather I should do one of: a) try to better understand the argument and find a more specific crux to disagree on or b) decide that this topic isn't worth investing more time in, register it as "not sure if X is true" in my mind, and move on.

there are policies which are successful because they describe a particular strategy to follow (non-mesaoptimizers), and policies that contain some strategy for discovering more strategies (mesaoptimizers). a way to view the relation this has to speed/complexity priors that doesn't depend on search in particular is that policies that work by discovering strategies tend to be simpler and more generic (they bake in very little domain knowledge/metis, and are applicable to a broader set of situations because they work by coming up with a strategy for the task ...

random brainstorming about optimizeryness vs controller/lookuptableyness:

let's think of optimizers as things that reliably steer a broad set of initial states to some specific terminal state seems like there are two things we care about (at least):

- retargetability: it should be possible to change the policy to achieve different terminal states (but this is an insufficiently strong condition, because LUTs also trivially meet this condition, because we can always just completely rewrite the LUT. maybe the actual condition we want is that the complexity of t

a tentative model of ambitious research projects

when you do a big research project, you have some amount of risk you can work with - maybe you're trying to do something incremental, so you can only tolerate a 10% chance of failure, or maybe you're trying to shoot for the moon and so you can accept a 90% chance of failure.

budgeting for risk is non negotiable because there are a lot of places where risk can creep in - and if there isn't, then you're not really doing research. most obviously, your direction might just be a dead end. but there are also other t...

https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.08612 : interesting paper with improvement on straight through estimator

the phenomenon of strange bedfellows is probably caused in no small part by outgroup vs fargroup dynamics

'And what ingenious maneuvers they all propose to me! It seems to them that when they have thought of two or three contingencies' (he remembered the general plan sent him from Petersburg) 'they have foreseen everything. But the contingencies are endless.'

We spend a lot of time on trying to figure out empirical evidence to distinguish hypotheses we have that make very similar predictions, but I think a potentially underrated first step is to make sure they actually fit the data we already have.

Is the correlation between sleeping too long and bad health actually because sleeping too long is actually causally upstream of bad health effects, or only causally downstream of some common cause like illness?

Unsupervised learning can learn things humans can't supervise because there's structure in the world that you need deeper understanding to predict accurately. For example, to predict how characters in a story will behave, you have to have some kind of understanding in some sense of how those characters think, even if their thoughts are never explicitly visible.

Unfortunately, this understanding only has to be structured in a way that makes reading off the actual unsupervised targets (i.e next observation) easy.

An incentive structure for scalable trusted prediction market resolutions

We might want to make a trustable committee for resolving prediction markets. We might be worried that individual resolvers might build up reputation only to exit-scam, due to finite time horizons and non transferability of reputational capital. However, shareholders of a public company are more incentivized to preserve the value of the reputational capital. Based on this idea, we can set something up as follows:

- Market creators pay a fee for the services of a resolution company

- There i

Levels of difficulty:

- Mathematically proven to be impossible (i.e perfect compression)

- Impossible under currently known laws of physics (i.e perpetual motion machines)

- A lot of people have thought very hard about it and cannot prove that it's impossible, but strongly suspect it is impossible (i.e solving NP problems in P)

- A lot of people have thought very hard about it, and have not succeeded, but we have no strong reason to expect it to be impossible (i.e AGI)

- There is a strong incentive for success, and the markets are very efficient, so that for partic

(random shower thoughts written with basically no editing)

Sometimes arguments have a beat that looks like "there is extreme position X, and opposing extreme position Y. what about a moderate 'Combination' position?" (I've noticed this in both my own and others' arguments)

I think there are sometimes some problems with this.

- Usually almost nobody is on the most extreme ends of the spectrum. Nearly everyone falls into the "Combination" bucket technically, so in practice you have to draw the boundary between "combination enough" vs "not combination enough to

Subjective Individualism

TL;DR: This is basically empty individualism except identity is disentangled from cooperation (accomplished via FDT), and each agent can have its own subjective views on what would count as continuity of identity and have preferences over that. I claim that:

- Continuity is a property of the subjective experience of each observer-moment (OM), not necessarily of any underlying causal or temporal relation. (i.e I believe at this moment that I am experiencing continuity, but this belief is a fact of my current OM only. Being a Boltzmann b

Imagine if aliens showed up at your doorstep and tried to explain to you that making as many paperclips as possible was the ultimate source of value in the universe. They show pictures of things that count as paperclips and things that don't count as paperclips. They show you the long rambling definition of what counts as a paperclip from Section 23(b)(iii) of the Declaration of Paperclippian Values. They show you pages and pages of philosophers waxing poetical about how paperclips are great because of their incredible aesthetic value. You would be like, "...

random thoughts. no pretense that any of this is original or useful for anyone but me or even correct

- It's ok to want the world to be better and to take actions to make that happen but unproductive to be frustrated about it or to complain that a plan which should work in a better world doesn't work in this world. To make the world the way you want it to be, you have to first understand how it is. This sounds obvious when stated abstractly but is surprisingly hard to adhere to in practice.

- It would be really nice to have some evolved version of calibration

Thought pattern that I've noticed: I seem to have two sets of epistemic states at any time: one more stable set that more accurately reflects my "actual" beliefs that changes fairly slowly, and one set of "hypothesis" beliefs that changes rapidly. Usually when I think some direction is interesting, I alternate my hypothesis beliefs between assuming key claims are true or false and trying to convince myself either way, and if I succeed then I integrate it into my actual beliefs. In practice this might look like alternating between trying to prove something ...

I think it might also depend on your goals. Like how fast you want to learn something. If you have less than ideal time, then maybe more structured learning is necessary. If you have more time then periods of structureless/passive learning could be beneficial.