Sometimes I'm at my command prompt and I want to draw a graph.

Problem: I don't know gnuplot. Also, there's a couple things about it that bug me, and make me not enthusiastic about learning it.

One is that it seems not really designed for that purpose. It implements a whole language, and the way to use it for one-off commands is just to write a short script and put it in quotes.

The other is its whole paradigm. At some point in the distant past I discovered ggplot2, and since then I've been basically convinced that the "grammar of graphics" paradigm is the One True Way to do graphs, and everything else seems substandard. No offense, gnuplot, it's just… you're trying to be a graphing library, and I want you to be a graphing library that also adheres to my abstract philosophical notions of what a graphing library should be.

If you're not familiar with the grammar of graphics, I'd summarize it as: you build up a graph out of individual components. If you want a scatter plot, you use the "draw points" component. If you want a line graph, you use the "draw line segments" component. If you want a line graph with the points emphasized, you use both of those components. Want to add a bar chart on top of that too? Easy, just add the "draw bars" component. Want a smoothed curve with confidence intervals? There's a "smooth this data" component, and some clever (but customizable) system that feeds the output of that into the "draw a line graph" and "draw a ribbon" components. Here's a gallery of things it can do

So, rather than adapt myself to the world, I've tried to adapt the world to myself.

There's a python implementation of the paradigm, called plotnine.1 (It has its own gallery.) And now I've written a command-line interface to plotnine.

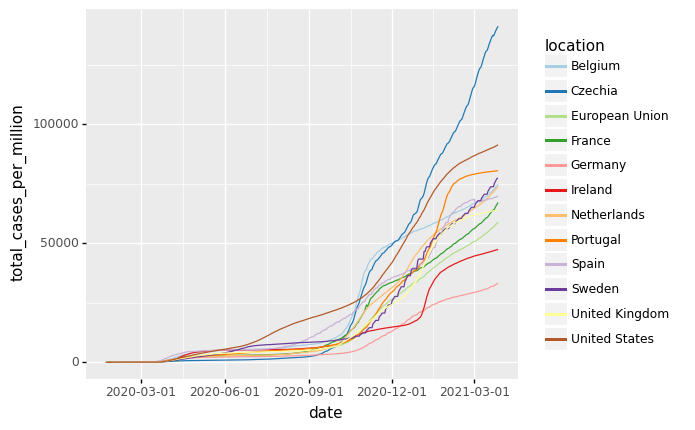

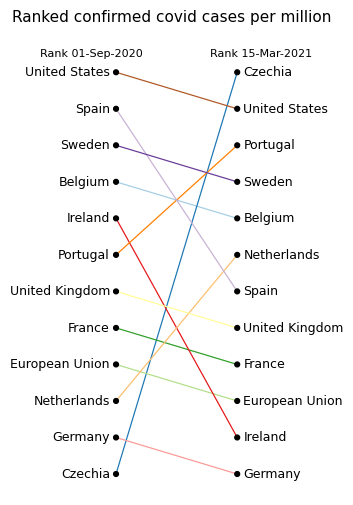

It's not as powerful as it plausibly could be. But it's pretty powerful2, and if I stop developing now I might find it fully satisfies my needs in future. For example, I took a dataset of covid cases-per-capita timeseries for multiple countries. Then both of these graphs came from the same input file, only manipulated by grep to restrict to twelve countries:

(The second one isn't a type of graph that needs to be implemented specifically. It's just a combination of the components "draw points", "draw line segments" and "draw text".)

Now admittedly, I had to use a pretty awful hack to get that second one to work, and it wouldn't shock me if that hack stops working in future. On the other hand, I deliberately tried to see what I could do without manipulating the data itself. If I wasn't doing that, I would have used a tool that I love named q, which lets you run sql commands on csv files, and then there'd be no need for the awful hack.

Anyway. If you're interested, you can check it out on github. There's documentation there, and examples, including the awful hack I had to use in the above graph. To set expectations: I don't anticipate doing more work on this unprompted, in the near future. But if people are interested enough to engage, requesting features or contributing patches or whatever, I do anticipate engaging back. I don't want to take on significant responsibility, and if this ever became a large active project I'd probably want to hand it over to someone else, but I don't really see that happening.

-

I'm aware of two other things that could plausibly be called python implementations of the grammar of graphics, but on reflection I exclude them both.

The first is a package that used to literally be called ggplot. The creator of the original ggplot2 (if there was a prior non-2 ggplot, I can't find it) pointed out that the name was confusing, so it got renamed to ggpy, and now it's defunct anyway. But I don't count it, because under the hood it didn't have the grammar thing going on. It had the surface appearance of something a lot like ggplot2, but it didn't have the same flexibility and power.

The other is one I started writing myself. I exclude it for being nowhere near complete; I abandoned it when I discovered that plotnine existed and was further along. I did think mine had the nicer API - I was trying to make it more pythonic, where plotnine was trying to be a more direct translation of ggplot2. But that hardly seemed to matter much, and if I really cared I could implement my API on top of plotnine.

I only remember two things plotnine was missing that I supported. One was the ability to map aesthetics simultaneously before and after the stat transform (ggplot2 only allows one or the other for each aesthetic). I'm not convinced that was actually helpful. Coincidentally, a few days ago plotnine 0.8.0 came out with the same feature, but more powerful because it supports after-scale too. The other was a rudimentary CLI, and now plotnine has one of those too. ↩

-

Most of this power, to be clear, comes from plotnine itself, from the grammar of graphics paradigm, and from python's scientific computing ecosystem. My own contribution is currently less than 250 lines of python; I may have used some design sense not to excessively limit the power available, but I didn't provide the power. ↩

Substance: is grammar of graphics actually a good paradigm? It's a good question, and I'm not convinced my "it's the One True Way" feeling comes from a place of "yes I have good reason to think this is a good paradigm". I haven't actually thought much about it prior to this, so the rest of my comment is kind of tentative.

So let's say for now we don't need any form of interactivity, it's fine to just think of a plot as being a list of pixels. I'm not sure we do have the tradeoff you describe? Certainly it's not a one-dimensional one. You could imagine a program that forces you to just set every pixel, and then you could imagine that it adds functions for "draw a line", "draw a filled-in rectangle", but you still have access to the raw pixels. And then it can add "draw a bar chart" and "draw a line graph", and so on, all the way up to "draw a quasi rectiliniar radial spiral helix fourier plot", and it never needs to lose access to "draw a raw pixel".

The awkward thing is, once you have "draw a bar chart" etc., the programmer doesn't necessarily know which pixels will get set, and at that point "draw a pixel" becomes a lot less useful. But that's kind of true with the lower-level primitives too, as soon as you start calling them based on runtime data. Is there space in one corner to place the legend? That's not necessarily easier to figure out when you're just drawing pixels than when you're calling a high-level "draw graph" function.

(Though it might be less differential effort. Like, if you're already looping through your data manually, you can add a flag for any points in the corner. If you're just passing your data to another function that loops through it, you now need to add a manual loop. And if you don't know exactly where that other function draws, based on the data, maybe you don't know when to set that flag... but the worst case scenario is that function doesn't make your life easier, and then you can just not use it.)

Where I'm going at with this: okay, suppose you're using plotnine and it doesn't implement the kind of plot you want. Is it any harder to implement that plot in plotnine than it would be in matplotlib? I'm not sure it is. If you want to balance several small bars on top of a big one, in matplotlib you need to figure out the x,y,w,h (or equivalent) of a bunch of rectangles. In plotnine, if you have the x,y,w,h of a bunch of rectangles, you can just draw them. It's maybe a little more friction, for example you might be less familiar with the "draw an arbitrary rectangle" component than the "draw a rectangle given just x,h" component that figures out y,w for you (and is probably implemented in terms of the previous). But, I guess it feels like relatively low friction compared to the hassle of figuring out the coordinates.

So that's part of my answer. You say there's a tradeoff to be made, but I'm not sure a grammar of graphics is taking significant losses on that tradeoff.

And on the other hand, is it making significant gains?

A naive answer: each layer in ggplot or plotnine has a "geom", a "stat" and a "position". You can mix-and-match these, so O(l+m+n) effort gives you O(lmn) types of graph.

This is obviously silly. Some of the elements aren't compatible with each other, and some of those types of graph you'd never want. But do you get some gains in that direction? It seems to me that you do; the same position adjustment ("dodge") that puts your bars in a bar chart side-by-side will probably put your boxplots side-by-side too. On the other hand it might not be loads - it looks like most stats are implemented for specific geoms, for example. There's only one geom that uses stat_boxplot by default, and only one that uses stat_ydensity, and stat_smooth. You could use stat_boxplot with a geom other than geom_boxplot, but I don't know if you ever would. I guess one thing you do get from this setup is, with a clear distinction between the statistical transformation and the data-drawing, you're unlikely to ever say "aw man, this boxplot-drawing function expects me to pass in my raw data to compute the statistics itself, but I already have the statistics and I threw out the raw data". That's fine, you just use geom_boxplot with stat_identity.

So, I guess my sense is that a grammar of graphics does help make things easier, relative to lower-level things. Like, makes more types of things easy, with less effort (and less forethought) needed from the people making the existing things.

But I'm not super confident about either of these, and this is almost entirely theoretical, so.