This is a linkpost to an article by Ege Erdil and I that we wrote to explain an important perspective that we share regarding AI automation. I'll quote the introduction:

A popular view about the future impact of AI on the economy is that it will be primarily mediated through AI automation of R&D. In some form or another, this view has been expressed by many influential figures in the industry:

- In his essay “Machines of Loving Grace”, Dario Amodei lists five ways in which AI can benefit humanity in a scenario where AI goes well. He considers biology R&D, neuroscience R&D, and economics R&D as three of these ways. There’s no point at which he clearly argues that AI will lead to high rates of economic growth due to being broadly deployed throughout the economy as opposed to speeding up R&D and perhaps improving economic governance.

- Demis Hassabis, CEO of DeepMind, is also bullish on R&D as the main channel through which AI will benefit society. In a recent interview, he provides specific mechanisms through which this could happen: AI could cure all diseases and “solve energy”. He mentions “radical abundance” as a possibility as well, but beyond the R&D channel doesn’t name any other way in which this could come about.

- In his essay “Three Observations”, Sam Altman takes a more moderate position and explicitly says that in some ways AI might end up like the transistor, a big discovery that scales well and seeps into every corner of the economy. However, even he singles out the impact of AI on scientific progress as likely to “surpass everything else”.

Overall, this view is surprisingly influential despite not having been supported by any rigorous economic arguments. We’ll argue in this issue that it’s also very likely wrong.

R&D is generally not as economically valuable as people assume—increasing productivity and new technologies are certainly essential for long-run growth, but the contribution of explicit R&D to these processes is smaller than people generally think. Moreover, even most of this contribution is external and not captured in profits by the company performing the R&D, reducing the incentive to deploy systems to perform R&D in the first place. This combination means most AI systems will actually be deployed and earn revenue from tasks that are unrelated to R&D, and in aggregate these tasks will be more economically valuable as well.

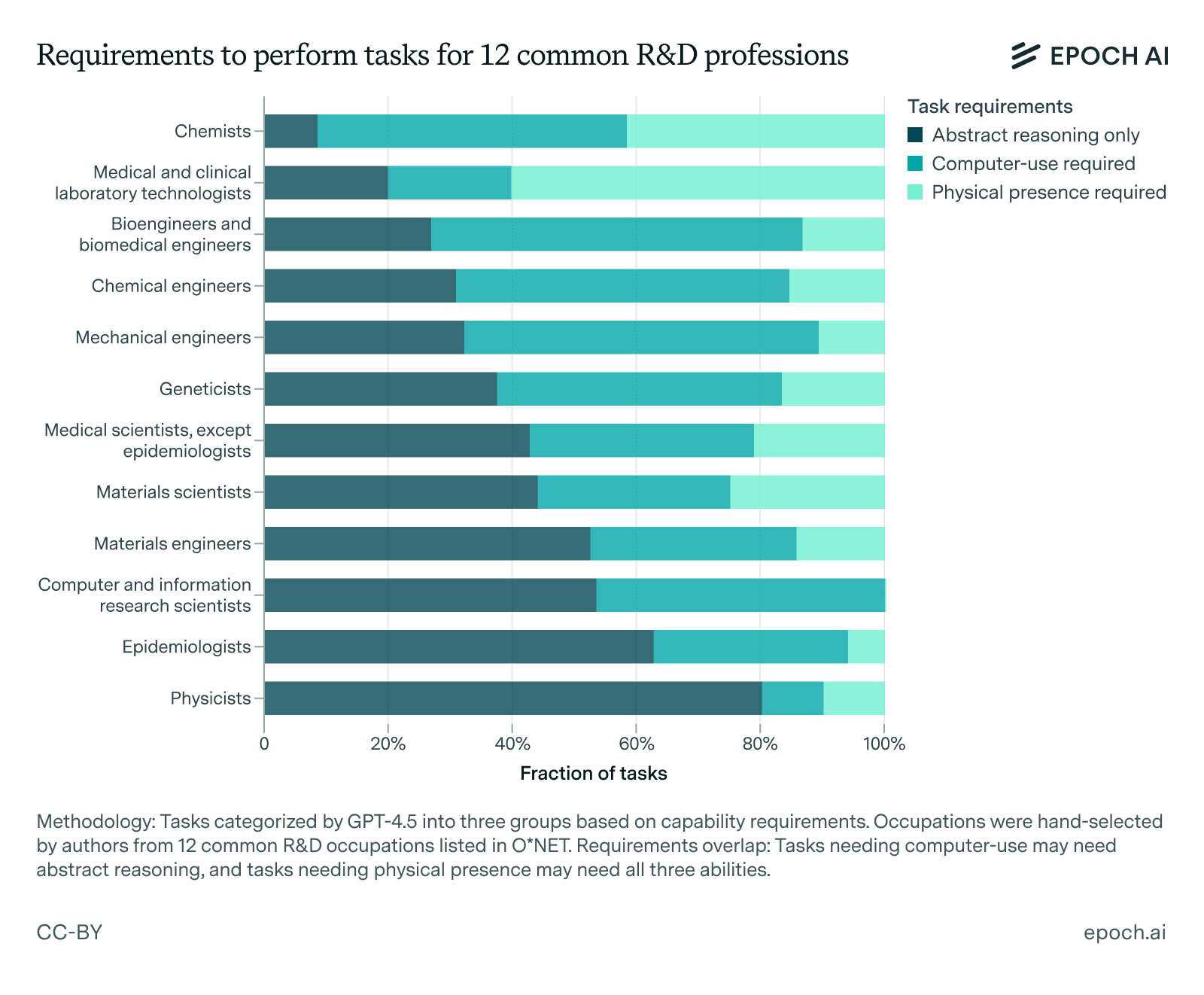

It’s also significantly harder to automate R&D jobs than it might naively seem, because most tasks in the job of a researcher are not “reasoning tasks” and depend crucially on capabilities such as agency, multimodality, and long-context coherence. Once AI capabilities are already at a point where the job of a researcher can be entirely automated, it will also be feasible to automate most other jobs in the economy, which for the above reason would most likely create much more economic value than narrowly automating R&D alone.

When we combine these two points, there’s no reason to expect most of the economic value of AI to come from R&D at any point in the future. A much more plausible scenario is that the value of AI will be driven by broad economic deployment, and while we should expect this to lead to an increase in productivity and output per person due to increasing returns to scale, most of this increase will probably not come from explicit R&D.

Here's a link to the full article.

It's important to be precise about the specific claim we're discussing here.

The claim that R&D is less valuable than broad automation is not equivalent to the claim that technological progress itself is less important than other forms of value. This is because technological progress is sustained not just by explicit R&D but by large-scale economic forces that complement the R&D process, such as general infrastructure, tools, and complementary labor used to support the invention, implementation, and deployment of various technologies. These complementary factors make it possible to both run experiments that enable the development of technologies and diffuse these technologies widely after they are developed in a laboratory environment—providing straightforwardly large value.

To provide a specific operationalization of our thesis, we can examine the elasticity of economic output with respect to different inputs—that is, how much economic value increases when a particular input to economic output is scaled. The thesis here is that automating R&D alone would, by itself, raise output by significantly less than automating labor broadly (separately from R&D). This is effectively what we mean when we say R&D has "less value" than broad automation.