(EDIT 2025-03-15: I've added a comment which you might want to read after the post.)

Follow up to: Could orcas be smarter than humans?

(For speed of writing, I mostly don't cite references. Feel free to ask me in the comments for references for some claims.)

This post summarizes my current most important considerations on whether orcas might be more intelligent than humans.

Evolutionary considerations

What caused humans to become so smart?

(Note: AFAIK there's no scientific consensus here and my opinions might be nonstandard and I don't provide sufficient explanation here for why I hold those. Feel free to ask more in the comments.)

My guess for the primary driver of what caused humans to become intelligent is the cultural intelligence hypothesis: Humans who were smarter were better at learning and mastering culturally transmitted techniques and thereby better at surviving and reproducing.

The book "the secret of our success" has a lot of useful anecdotes that show the vast breath and complexity of techniques used by hunter gatherer societies. What opened up the possibility for many complex culturally transmitted techniques was the ability of humans to better craft and use tools. Thus the cultural intelligence hypothesis also explains why humans are the most intelligent (land) animal and the animals with the best interface for crafting and using tools.

Though it's possible that other factors, e.g. social dynamics as described by the Marchiavellian Intelligence Hypothesis, also played a role.

Is it evolutionarily plausible that orcas became smarter?

Orcas have culturally transmitted techniques too (e.g. beach hunting, making waves to wash seals off ice shells, faking retreat tactics, using bait to catch birds, ...), but not (as far as we can tell) close to the sophistication of human techniques which were opened up by tool use.

I think it's fair to say that being slightly more intelligent probably resulted in a significantly larger increase in genetic fitness for humans than for orcas.

However, intelligence also has its costs: Most notably, many adaptations which increase intelligence route through the brain consuming more metabolic energy, though there are also other costs like increased childbirth mortality (in humans) or decreased maximum dive durations (in whales).

Orcas have about 50 times the daily caloric intake of humans, so they have a lot more metabolic energy with which they could power a brain that consumes more energy (and can thereby do more computation). Thus, the costs of increasing intelligence is a lot lower in orcas.

So overall it seems like:

- intelligence increase in humans: extremely useful for reproduction; also very costly

- intelligence increase in orcas: probably decently useful for reproduction; only slightly costly

Though it's plausible that (very roughly speaking) past the level of intelligence needed to master all the cultural orca techniques (imagine IQ80 or sth) it's not very reproductively beneficial for orcas to be smarter for learning cultural techniques. However, even though I don't think it's the primary driver of human intelligence evolution, it's plausible to me that some social dynamics caused selection pressures for intelligence that caused orcas to become significantly smarter. (I think this is more plausible in orcas than in humans because intelligence is less costly for orcas so there's lower group-level selection pressure against intelligence.)

Overall, from my evolutionary priors (aka if I hadn't observed humans evolving to be smart) it seems roughly similarly likely that orcas develop human-level+ intelligence as that humans do. If one is allowed to consider that elephants aren't smarter than humans, then perhaps a bit higher priors for humans evolving intelligence.[1]

Behavioral evidence

Anectdotes on orca intelligence:

- Orcas leading orca researcher on boat 15miles home through the fog. (See the 80s clip starting from 8:10 in this youtube video.)

- Orcas can use bait.

- An orca family hunting a seal can pretend to give up and retreat and when the seal comes out thinking it's safe then BAM one orca stayed behind to catch it. (Told by Lance Barrett-Lennard somewhere in this documentary.[1])

- Intimate cooperation between native australian

hunter gathererswhale hunters and orcas for whale hunting around 1900: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Killer_whales_of_Eden,_New_South_Wales- Orcas being skillful at turning boats around and even sinking a few vessels[2][3]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iberian_orca_attacks

- Orcas have a wide variety of cool hunting strategies. (e.g. see videos (1, 2)).

Two more anecdotes showing orcas have high dexterity:

- One orca in captivity caught a bird and manipulated it's internals until only the heart with the wings remained and then presented it to one orca trainer.

- When there landed a mother duck with their chicks trailing behind her on the orca pool, an orca managed to sneak up from behind and plug the chicks one by one from behind without the chicks and ducks at the front even noticing that something happened.

Also, some orca populations hunt whales much bigger than themselves, like calfs of humpback, sperm, or blue whales. Often by separating them from their mother and drowning them.

Evidence from wild orcas

(Leaving aside language complexity, which is discussed below,) I think what we observe from wild orcas, while not legibly as impressive as humans, would still be pretty compatible with orcas being smarter than humans (since it's find sth we don't observe, but what we probably would expect to see if they were as smart as us).

(Orcas do sometimes get stuck in fishing gear, but less so than other cetaceans. Hard to tell whether humans in orca bodies would get stuck more or less.)

(I guess if they were smarter in abstract reasoning than the current smartest humans, maybe I'd expect to see something different, though hard to say what. So I think they are currently not quite super smart, but it's still plausible that they have the potential to be superhumanly smart, and that they are currently only not at all trained in abstract reasoning.)

Evidence from orcas in captivity

I mostly know of a couple of sublte considerations and pieces of evidence here, and don't share them in detail but just give some overview.

I think overall the observations are very weak evidence against orcas being as smart as humans, and nontrivial evidence against them being extremely smart. (E.g. if they were very extremely smart they maybe could've found a way to teach trainers some simple protolanguage for better communicating.)

I'm not sure here, but e.g. it doesn't seem like orcas learn tricks significantly faster than bottlenose dolphins, but maybe the bottleneck is just communication ability for what you want the animals to do. (EDIT: Actually orcas seem to often learn tricks a bit slower than bottlenose dolphins, though orcas are also often a lot less motivated to participate.) Still, I'd sorta have expected something more impressive, so some counterevidence.

Thoughts on orca languages

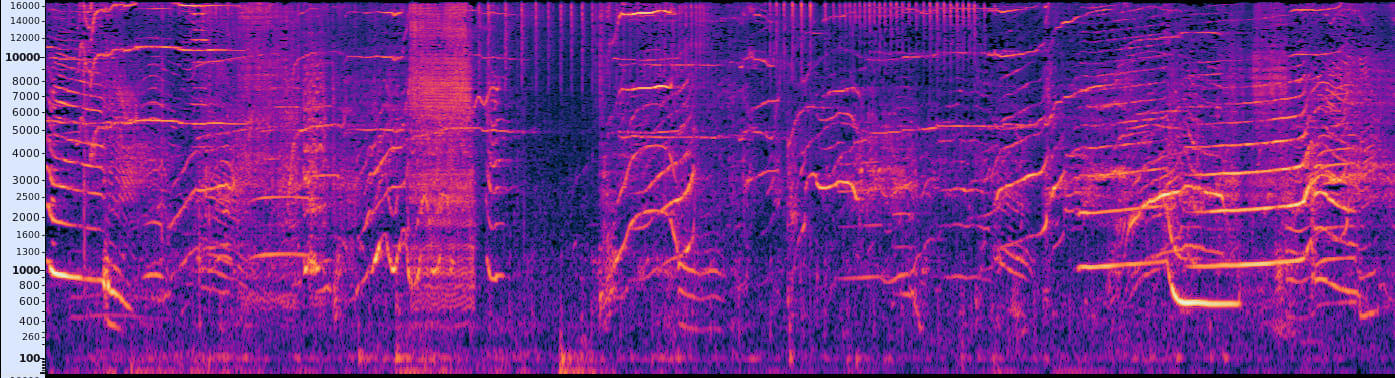

I have quite some difficulty to relatively quickly estimate the complexity of orca language. I could talk a bunch about subtleties and open questions, but overall it's like "it could be anything from a lot less complex to a significantly more sophisticated than human language". I'd say it's slight evidence against full human-level language complexity. (Feel free to ask for more detail in the comments. Btw, there are features of orca vocalizations which are probably relevant and which are not visible in the spectrogram.)

Very few facts:

Orca language is definitely learned; different populations have different languages and dialects.

It takes about 1.5 years after birth[2] for orca calfs to fully learn the calls of their pod (though it's possible that there's more complexity in the whistles, and also there are more subclusters of calls which are being classified as the same calltype).

Louis Herman's research on teaching bottlenose dolphins language understanding

In the 80s, Louis Herman et al taught bottlenose dolphins to execute actions defined through language instructions. The experiments used proper blinding and the results seem trustworthy. Results include:

- Dolphins were able to correctly learn that the order of words mattered: E.g. for "hoop fetch ball" they took the hoop and put it to the ball, whereas for "ball fetch hoop" they did it vice versa.

- Dolphins were in some sense able to learn modifier words like "left/right": E.g. when there was both a left and a right ball, then "mouth left ball" they usually managed to correctly grasp the left ball with their mouths.

- They also often correctly executed composite commands like "surface pipe fetch bottom hoop" (meaning the dolphin needs to bring the pipe on the surface to the hoop at the bottom (where presumably there were multiple pipes and hoops present)).

- (They allegedly also showed that dolphins could learn the concepts "same"/"different", though I didn't look that deeply into the associated paper.)

AFAIK, this is the most impressive demonstration of grammatical ability in animals to date. (Aka more impressive than great apes in this dimension. (Not sure about parrots though, though I haven't yet heard of convincing grammar demonstrations as opposed to it just being speech repetition.))

In terms of evolutionary distance and superficial brain-impressiveness, orcas are to bottlenose dolphins roughly as humans are to chimps, except that the difference between orcas and bottlenose dolphins is even a big bigger than between humans and chimps, so this is sorta promising.

Neuroscientific considerations

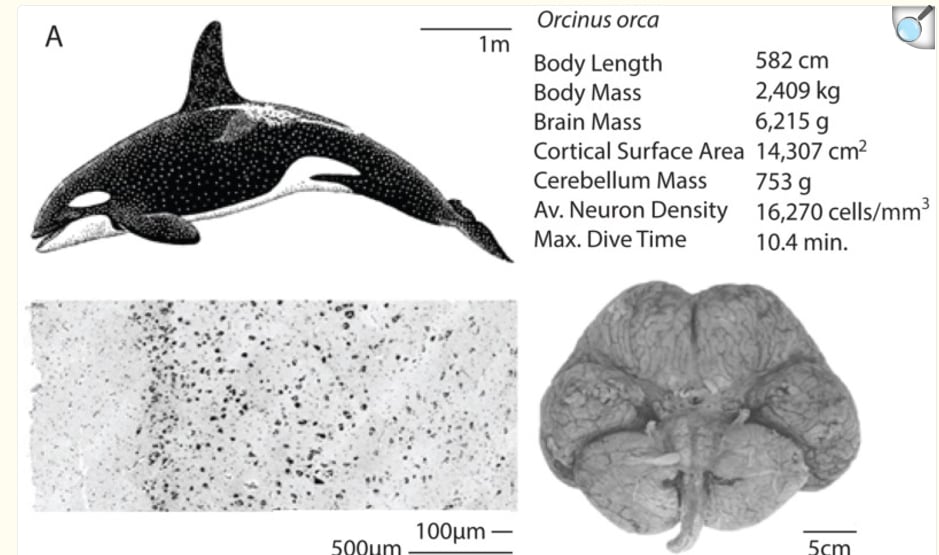

Orca brain facts

(Warning: "facts" is somewhat exaggerated for the number of cortical neurons. Different studies for measuring neural densities sometimes end up having pretty different results even for the same species. But since it was measured through the optical fractionator method, the results hopefully aren't too far off.)

Orcas have about 43 billion cortical neurons - humans have about 21 billion. The orca cortex has 6 times the area of the human cortex, though the neuron density is about 3 times lower.

Interspecies correlations between cortical neurons and behavioral signs of intelligence

(Thanks to LuanAdemi and Davanchama for much help with this part.)

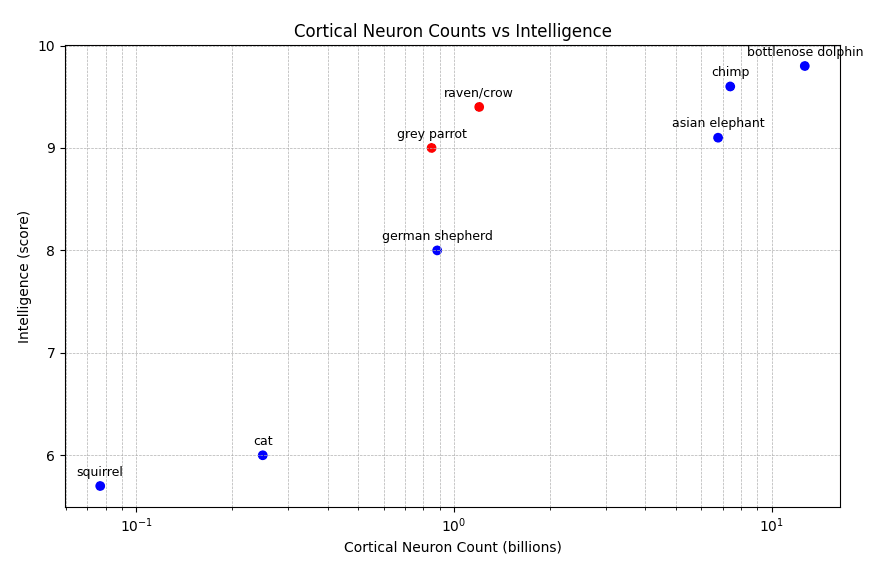

I've tried to estimate the intelligence of a few species based on their behavior and assigned each species a totally subjective intelligence score, and a friend of mine did the same, and I roughly integrated the estimates together to what seems like a reasonable guess. Though of course the intelligence scores are very debateable. Here are the results plotted together with the species' numbers of cortical neurons[3]:

As can be seen, the correlation is pretty strong, especially within mammals (whereas the birds are a bit smarter than I'd estimate from cortical neuron count). (Though if I had included humans they would be an outlier to the top. The difference between humans and bottlenose dolphins seems much bigger than between bottlenose dolphins and chimps, even though the logarithmic difference in cortical neuron count is similar.)

(Also worth noting that average cortical neural firing rates don't need to be the same across species. Higher neuron densities might correlate with quicker firing and thus more actual computation happening. That birds seem to be an intelligent outlier above is some evidence for this, though it could also be that the learning algorithms of a bird's pallium is just a bit more efficient than that of the mammalian cortex or so.)

How much does scale vs other adaptations matter?

A key question is "how much does intelligence depend on scale vs other adaptations?".

Here are some rough abilities that seem useful for intelligence that seem like they might probably come in some way from non-upscaling adaptations (rather than just arising as side-effect of upscaling):

- Metacognition - the ability to notice thoughts themselves

- relatedly, perhaps some adaptations for better language processing

- Social learning abilities - paying attention to the right things and imitating actions of conspecifics

- Type 2 (formerly called System 2) reasoning

- better attention control

- having control-flow thoughts for managing other thoughts

- Having a detailed self-concept and sense of self

(Some of those might already exist to some extent in non-human land mammals too though.)

It's also conceivable that humans got more adaptations that e.g. increased the efficiency of synapsogenisis or improved the learning algorithms somewhat, though personally I'd not expect that a few million years of strong selection for intelligence in humans were able to produce very significant improvements here.

We should expect humans to have more of those non-scaling intelligence improving mutations: Orcas are much bigger than humans, so the fraction of the metabolic cost the brain consumes is smaller than in humans. Thus it took more selection pressure for humans to evolve having 21billion neurons than for orcas to have 43billion.[1] Thus humans might have other intelligence-increasing mutations that orcas didn't evolve yet.

The question is how important such mutations are in contrast to scaling up? And in so far as they matter, were they hard to evolve or easy to evolve once the brain was large enough to make use of metacognitive abilities?

My uncertain guess is that, within mammalian brains, scaling matters a lot more for individual intelligence, and that most of the subtleties of intelligence (e.g. abstract pattern recognition or the ability to learn language) don't require hard-to-evolve adaptations. (Though better social learning was probably crucial for humans developing advanced cultural techniques. Also, it's not like I think scale alone determines the full cognitive skill profile: I think there are other adaptations that can trade off different cognitive abilities, as possibly unrealistic example e.g. between memory precision and context generalization.)

Overall guess

Having read the above, you might want to try to think for yourself how likely you think it is that orcas are as smart or smarter than humans, before getting contaminated with my guess. (Feel free to post your guess in the comments.)

Orca intelligence is very likely going to be shaped in a somewhat different way than human intelligence. Though to badly quantify my estimates on how smart average orcas might be (in some rough "potential for abstract reasoning and learning" sense):

I'd say 45% that average orcas are >=-2std relative to humans, and 20% that they are >=6std.[4]

Aside: Update on my project

Follow up to: Orca communication project

I'm currently trying to convince a facility with captive orcas to allow me to do my experiment there, but the chances are mediocre. Else I'll try to see whether I can do the experiments with wild orcas, though it might be harder to get much interaction time and it requires getting a permit for doing the experiment with wild orcas, which might also be hard to get.

I'm now no longer searching for collaborators for doing the relevant technical language research work (though still reach out if interested)[5]. However, I'm looking for:

- Someone who performs the experiments with me and documents the results. (Bonus points if you're a biologist (because it might make getting a permit slightly easier).)

- Someone (e.g. a very competent PA) for: helping me to reach out to potential collaborators; research how hard it might be to get permits where; research easy it might be to do experiments in particular places (e.g. how much orca pods are moving there); research what equipment to best use; and later work on getting permits.

Those 2 roles can be filled by the same person. If you might be interested in filling one or both of those roles, please message me so we can have a chat (and let me know roughly how much money you'd want).

- ^

In case you're wondering, no this isn't a hindsight prediction from me having observed orca's large brains. Orcas are the largest animal engaging in collaborative hunting. Sperm whales would also be roughly similarly likely to develop intelligence on my evolutionary priors - they have even more metabolic energy though they are less social than orcas.

- ^

Note that orcas have about 17 months gestation period.

- ^

For asian elephants we actually don't have measurements, so I took estimated values from wikipedia, though hopefully the estimates aren't too bad since we have measurements for african elephants. Also measurements can be faulty.

- ^

Though again, it's about potential for if they got similar education or so. I'd relatively strongly expect very smart humans to win against current orcas in abstract reasoning tests, even if orcas have higher potential.

- ^

A smart friend of my tried to do the research but it seems like I'm just unusually good and fast at this research and it didn't seem like I could be sped up significantly, so I'm planning to do the technical research myself and find good ways to delegate the other work to other competent people.

This post seems to assume that a 2x increase in brain size is a huge difference (claiming this could plausibly yield +6SD), but a naive botec doesn't support this.

For humans, brain size and IQ are correlated at ~0.3. Brain size has a standard deviation of roughly 12%. So, a doubling of brain size is ~6 SD of brain size which yields ~1.8 SD of IQ. I think this is probably a substantial overestimate as I don't expect this correlation is fully causal: increased brain size is probably correlated with factors that also increase IQ through other mechanisms (e.g., generally fewer deleterious mutations, aging, nutrition). So, my bottom line guess is that doubling brain size is more like 1.2 SD of IQ. This implies that doubling brain size isn't that big of a deal relative to other factors.

I think this is basically the bottom line--quite likely doubling brain size isn't very decisive, but I did a more detailed botec to get to a (sloppy) bottom line out of curiosity.

First let's account for non-brain size differences. My guess is that orcas are (median) around -4 SD on non-brain size differences (aka brain algorithms) with respect to research tasks (putting some weight on language specialization, accounting for orca specialization, etc.), for an overall estimate of -2.8 SD. This doesn't feel crazy to me?

Where does this -4 SD come from? My guess is that the human-chimp gap in non-brain size improvements is around 2.2 SD[1] and the chimp-orca (non-brain size) gap is probably similar, maybe a bit smaller, let's say 1.8 SD. So, this yields -4 SD.

I think my 95% confidence internal for the orca algorithmic advantage (on research) is like -8 SD to -1 SD with a roughly normal distribution. (I could be argued into having a substantially lower value for the bottom of the confidence internval; -12 SD doesn't seem too crazy.)

To get a interval for IQ vs brain size effect, let's do a very charitable estimate and then use this as a 95th percentile. The maximally charitable estimate would be something like:

Using this as a 95th percentile and 1.2 as my median, my 95% confidence internal is like 0.4 to 3.6 SDs per 2xing (putting aside the probability of this whole model being confused). Let's say this is distributed lognormally.

Now, let's say 95% interval on ocra brain size as 1.5 to 2.5. (With a log normal distribution.)

This yields ~5% chance of orcas being over 4SDs above humans. And ~10% chance of >2SDs. (See the notebook here.) After updating on our observations (humans appear to be running an intelligent civilization and orcas don't seem that smart), I update down by maybe 5x on both of these estimates to 1% chance of >4SDs and 2% chance of >2SDs.

Correspondingly, I'm not very optimistic about the prospects here.

I think the chimp vs human gap is probably roughly half brain size and half other (algorithmic) improvements. The brain size gap is 3.5x or 2.2 SD (using 1.2 SD / doubling). So, if the gap is half brain size and half other (algorithmic) improvements, then we'd get 2.2 SD of algorithmic improvement. ↩︎

Yeah I think I came to agree with you. I'm still a bit confused though because intuitively I'd guess chimps are dumber than -4.4SD (in the interpretation for "-4.4SD" I described in my other new comment).