I am not much of an economist, but the two thoughts that spring to mind:

- The change you want to see, of people not needing to do as much work, is in fact happening (even if not as fast as you might like). The first clean chart I could find for US data was here, showing a gradual fall since 1950 from ~2k hours/year to ~1760 hours/year worked. This may actually understate the amount of reduction in poverty-in-the-sense-of-needing-to-work-hard-at-an-unpleasant-job:

- I think there has also been a trend towards these jobs being much nicer. The fact that what you're referring to as a 'miserable condition' is working a retail job where customers sometimes yell at you, rather than working in the coal mines and getting blacklung, is a substantial improvement!

- I think there has also been a trend towards the longest-hours-worked being for wealthier people rather than poorer people. "Banker's hours" used to be an unusually short workday, which the wealthy bankers could get away with - while bankers still have a lot more money than poor people, I think there's been a substantial shift in who works longer hours.

The change you want to see, viewed through the right lens, is actually

On your definition of 'poverty', Disneyland makes the world poorer.

I think the comparison with Disneyland misses the point. The essay measures poverty by the level of desperation people experience. People don’t typically work extra hours out of desperation to take their kids to Disneyland; they do it out of a desire for additional enjoyment. The 60-hour work week should be understood as working far more hours than one would if they weren't desperate for essential resources.

Poverty is about lacking crucial resources necessary for living, not just lacking luxury items. Therefore, adding more Disneylands wouldn’t make people poorer, but people who are not poor might still strive for better things—from a position of security, not desperation. Interestingly, this aligns with your argument right above that "work produces nice enough stuff that people are willing to do the work to produce it."

Short answer: Money is fungible.

Long answer: If you work 60 hours a week, buy essential items, and can't buy luxury items, it is reasonable to say that you needed to work 60 hours a week just to afford essential items. If you work 60 hours a week, buy essential items, and also buy luxury items, it seems more reasonable to say that you worked [X] hours a week to buy essential items and [60-X] hours a week to buy luxury items, for some X<60.

If you ignore the fungibility of money, you can say things like this:

- Bob works 40 hours a week. He spends half of this salary on essential items like food and clothing and shelter, and the other half on luxury items like fancy vacations, professionally prepared food, recent consumer electronics and entertainment, etc.

- Now Bob has children. Oh no! He now needs to work an extra 20 hours a week to afford to send his children to a good school! This means he needs to work 60 hours a week to afford necessities!

But, even if we account a good school as a necessity, Bob's actual situation is that he is spending 20 hours of labor on his personal necessities, 20 hours of labor on his children's necessities, and 20 hours...

The relation between time and money is sometimes not linear.

I would be happy to work 2/3 time for 2/3 of my current salary (doing things similar to what I am doing now), but I don't see such option on the job market. Most employers are "40 hours, or go away". The ones who offer part-time jobs typically pay way below the market salary, and still think they are doing you a favor.

(To generalize, this is my objection against the concept of "revealed preferences" -- sometimes the options we imagine intentionally rejected by other people were never real for them in the first place.)

A large part of the family budget is "money passing through your hands". You get a salary. You pay for the mortgage, electric power, gas, car insurance, etc. Include some humble amount of food and occasional new clothes and shoes, and... if you have an average income, it is possible that maybe 90% of your salary is already gone at that moment. The remaining 10% are yours to spend as you wish.

My point is that the budget of average people has much less slack than it may seem -- at one moment you have a little discretionary spending, the next moment your expenses somehow increase by 15% (your car breaks, you get ...

I think the crux here is the "relative" poverty aspect. Comparison with others is actually really important, it turns out. Going to Disneyland isn't just a net positive; not going to Disneyland can be a negative if your kids expect you to and all their friends are. A lot of human activities are aimed at winning status games with other humans, and in that sense, in our society of abundance, marketing has vastly offset those gains by making sure it's painfully clear which things make you rich and which aren't worth all that much. So basically the Poverty Restoring force is "other people". No matter the actual material conditions there's always going to be by definition a bottom something percentile in status, and they'll be frustrated by this condition and trying to get out of it to earn some respect by the rest of society.

I think there has also been a trend towards the longest-hours-worked being for wealthier people rather than poorer people.

The data bears this out, at least for the United States. The top 10% of earners generally work an average of 4.4 hours/week more than the bottom 10% of earners in the US, although worldwide it seems they work 1 hour/week less, on average.

I have to think that this is one of those hard areas to get a consistent measure of a comment thing. For example, is the 3 hour lunch meeting with a client really the same as the 3 houts a factory worker put in or the three hours recorded by a software engineer records for a specific project worked on?

I suppose we can say in each cases there is some level of "standing around" rather than real work. But I do suspect that the types of work don't as one climbs the income ladder you start seeing more of the gray areas because the output of the effort becomes less directly measurable.

I also think that in the OP one of the factors in work was the unpleasant nature of the effort. While hardly universally true I have to speculate that at the higher income levels a larger percentage of people are doing things they find both interesting and enjoyable than hold at lower levels.

But clearly those hypothesis would likewise by challenging to evaluate as well.

Note: I crossposted this for Eliezer, after asking him for permission, because I thought it was a good essay. It was originally written for Twitter, so is not centrally aimed at a LW audience, but I still think it's a good essay ot have on the site.

+$BIGNUM for this. It's frustrating when interesting parts of the LW-sphere conversation happen on closed services. Some of us (e.g. and sometimes-feels-like-i.e. me) neither have nor want a twitter account, and twitter has made it increasingly difficult to follow references to it without one.

I have the same complaint about facebook, though it's not the culprit this time. Every so often I'll run into a post that depends on a reference that is facebook-account-walled.

From what I understand, they are using a forked version of Nitter which uses fully registered accounts rather than temporary anonymous access tokens, and sourcing those accounts from various shady websites that sell them in bulk.

I think this post would be much stronger if it tried to back up more of its empirical claims with evidence. For example, the post mentions people working 60 hours a week many times throughout, but my understanding is that <10% of American workers work 60 hours a week, and people who do tend to have much higher wages than average.

EDIT to add more: This post reads to me as making interesting and probably-somewhat-important valid-in-principle points, paired with the totally unjustified speculation that these points are important considerations for reasoning about poverty as it actually exists; it might be the case that this is right, but I don't see any way to check easily or any particular evidence that Eliezer's beliefs here are based on fact.

I actually disagree with this. I haven't thought too hard about it and might just not be seeing it, but on first thought I am not really seeing how such evidence would make the post "much stronger".

To elaborate, I like to use Paul Graham's Disagreement Hierarchy as a lens to look through for the question of how strong a post is. In particular, I like to focus pretty hard on the central point (DH6) rather than supporting and tangential points. I think the central point plays a very large role in determining how strong a post is.

Here, my interpretation of the central point(s) is something like this:

- Poverty is largely determined by the weakest link in the chain.

- Anoxan is a helpful example to illustrate this.

- It's not too clear what drives poverty today, and so it's not too clear that UBI would meaningfully reduce poverty.

I thought the post did a nice job of making those central points. Sure, something like a survey of the research in positive psychology could provide more support for point #1, for example, but I dunno, I found the sort of intuitive argument for point #1 to be pretty strong, I'm pretty persuaded by it, and so I don't think I'd update too hard in response to the survey o...

I just looked up Gish gallops on Wikipedia. Here's the first paragraph:

The Gish gallop (/ˈɡɪʃ ˈɡæləp/) is a rhetorical technique in which a person in a debate attempts to overwhelm an opponent by abandoning formal debating principles, providing an excessive number of arguments with no regard for the accuracy or strength of those arguments and that are impossible to address adequately in the time allotted to the opponent. Gish galloping prioritizes the quantity of the galloper's arguments at the expense of their quality.

I disagree that focusing on the central point is a recipe for Gish gallops and that it leads to Schrodinger's importance.

Well, I think that it in combination with a bunch of other poor epistemic norms it might be a recipe for those things, but a) not by itself and b) I think the norms would have to be pretty poor. Like, I don't expect that you need 10/10 level epistemic norms in the presence of focusing on the central point to shield from those failure modes, I think you just need something more like 3/10 level epistemic norms. Here on LessWrong I think our epistemic norms are strong enough where focusing on the central point doesn't put us at risk of things like Gish gallops and Schrodinger's importance.

Over at Astral Codex Ten is a book review of Progress and Poverty with three follow-up blog posts by Lars Doucet. The link goes to the first blog post because it has links to the rest right up front.

I think it is relevant because Progress and Poverty is the book about:

...strange and immense and terrible forces behind the Poverty Equilibrium.

The pitch of the book is that the fundamental problem is economic rents deriving from private ownership over natural resources, which in the book means land. As a practical matter the focus on land rents in the book heavily overlaps the modern discussion around housing. The canonical example of the problem is what a landlord charges to rent an apartment.

One interesting point is that while UBI is suggested (here called a Citizen's Dividend), it is for justice reasons, and is not proposed as a solution to poverty. I expect Henry George would agree that a UBI would not eliminate poverty, and would predict it mostly gets gobbled up by the immense and terrible forces behind the Poverty Equilibrium.

In many parts of Europe nobody has to work 60-hour weeks just to send their kids to a school with low level of violence. A bunch of people don't work at all and still their kids seem to have all teeth in place and get some schooling. Not sure what we did here that the US is failing to do, but I notice that the described problem of school violence is a cultural problem -- it's related to poverty, but is not directly caused by it.

I agree that there seems to be something uniquely wrong with USA (or maybe it's just a different trade-off than other countries have -- it's difficult to guess which problems are part of a greater equation, and which ones are accidental), but that doesn't answer the central question -- if, judging by looking at some economical numbers, poverty already doesn't exist for centuries, why do we feel so poor; or perhaps, why do we act as if we are poor.

- it could be that some important numbers are missing from the official set (the oxygen in Anoxia);

- it could be that the extractive systems adapt (give UBI -> increase rent);

- or it could be something else.

The feeling of poverty, either immediate, or breathing down our necks, is definitely in Europe, too. The absence of that feeling would be... something like a form of "early retirement" where people say that they still keep working, but it's only because they enjoy it or want more money, but if the work became unpleasant or abusive, they could quit it any time they would want to. Most people don't have this.

Let's not forget that people who read LW, often highly intelligent and having well-paying jobs such as software development, are not representative of the average population. Frankly, my life is quite easy, but it still has a lot of stress; so I imagine that for most people it is probably much worse. (For example, the entire Covid thing for me mostly meant "cool, now I can work from home", but other people have lost their jobs.)

if, judging by looking at some economical numbers, poverty already doesn't exist for centuries, why do we feel so poor

Let's not forget that people who read LW, often highly intelligent and having well-paying jobs such as software development

This underlines what I find so incongruous about EY's argument. I think I genuinely felt richer as a child eating free school meals in the UK but going to a nice school and whose parents owned a house than I do as an obscenely-by-my-standards wealthy person in San Francisco. I'm hearing this elaborate theory to explain why social security doesn't work when I have lived through and seen in others clear evidence that it can and it does. If the question “why hasn't a factor-100 increase in productivity felt like a factor-100 increase in productivity?” was levied at my childhood specifically, my response is that actually it felt like exactly that.

By the standards of low earning households my childhood was probably pretty atypical and I don't mean to say there aren't major systemic issues, especially given the number of people locked into bad employment, people with lives destroyed by addiction, people who struggle to navigate economic systems,...

do a nontrivial number of people in those parts of Europe work at soul-crushing jobs with horrible bosses?

Yes they do, at least when I meet people outside my bubble, such as someone working at Billa.

I think they do it simply because the rent is high (relatively to the income at the place where they live).

But working literally 60-hour weeks would be illegal. There are ways how employers try to push the boundary: They can make you do some overtime (but there is a limit how much total overtime per year is allowed). They can try to convince you that some work you do for them technically does not count as a part of your working time (e.g. your official working time is 8:00-16:30, but you need to arrive at 7:45 to get ready for your work, and at 16:30 the shop is officially closed, but you still need to clean up the place, check everything and lock the door, so you are actually leaving maybe at 17:00); I think they are lying about this, but I am not sure. Anyway, even these tricks do not get you to 60 hours per week.

I think the answer is simply that the modern world allows people to live with poverty rather than dying from it. It’s directly analogous to, possibly caused by, the larger increase in lifespan over healthspan and consequent failure of medicine to eliminate sickness. We have a lot of sick people who’d be dead if it weren’t for modern medicine.

There was an excellent study on the effect of Universal Basic Income (UBI) in the US that came out recently. OpenResearch calls it their Unconditional Cash Study. 1000$ per month unconditional tax-free, RCT. There are two papers that came out shortly after @ESYudkowsky's post:

The Employment Effects of a Guaranteed Income: Experimental Evidence from Two U.S. States by Eva Vivalt et al (this one refers to the study as OpenResearch Unconditional Income Study (ORUS), but I assume it is the same).

Does Income Affect Health? Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial of a Guaranteed Income by Sarah Miller et al.

Eva Vivalt has both listed on her blog.

My takeaway is:

- reduction of labor by 2h per week, replaced by leisure

- I think this is fine, actually. Less "by the sweat of your brow."

- reduction of (non UBI) income by 0.2$ per each $ UBI

- I think this is fine and to be expected, at least in the "short" run of the study. Where else would more money come from?

- no better quality jobs

- this is the sad result from the study that hints at the "poverty equilibrium" - UBI didn't help people avoid bad bosses.

- a little bit more education, a little bit of precursors to entrepreneurship

- no other relevant

I'm not sure the “poverty equilibrium” is real. Poverty varies a lot by country and time period, various policies in various places have helped with poverty, so UBI might help as well. Though I think other policies (like free healthcare, or fixing housing laws) might help more per dollar.

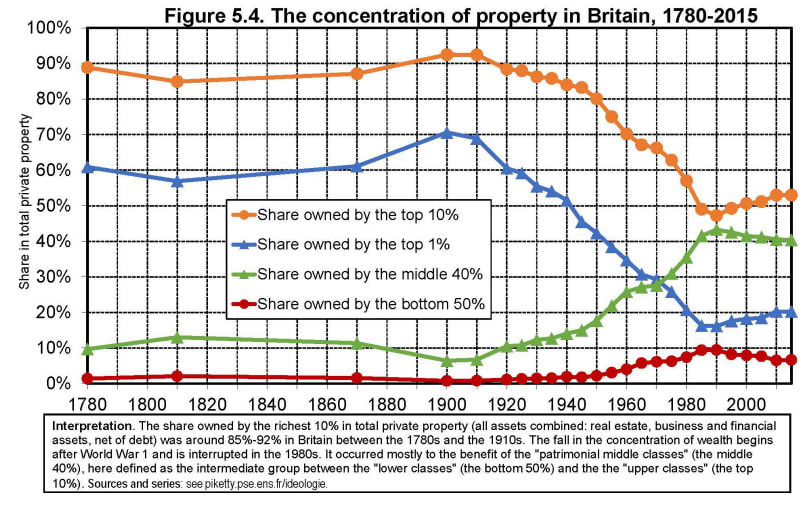

Agree; also this post doesn't seem to address e.g. the fact that the relative sizes of the social classes used to be quite different, and that today there exists a sizeable middle class rather than society being much more starkly divided into the poor vs. the wealthy.

[EDIT: replaced Claude's estimate of social class sizes with the following:]

E.g. this paper cites economist Thomas Piketty's research as the original source, shows the share of property owned by the middle 40% of the population in Britain going from 10% to 40% between 1780 and 2015, with the top 10% of the population had 85-90% of the property up to around 1940.

...Piketty (2020) has also been able to provide more distributional detail for the two most recent centuries, as shown in his Figure 5.4, reproduced here with permission (Piketty, 2020, p. 195). His estimates show that 1780–1800 saw a slight decline (from 89% to 86%) in the wealth proportion of the top 10% of private property holders, and an equivalent significant rise (from 10% to 13%) in the wealth held by the ‘middle 40%’, with the bottom 50% remaining at little more than 1% [...]

From [1910], however, the wealth of the top 10% began a gradual (1910–42) and

I wasn't sure what search term to use to find a good source on this but Claude gave me this:

I... wish people wouldn't do this? Or, like, maybe you should ask Claude for the search terms to use, but going to a grounded source seems pretty important to staying grounded.

Poverty equilibrium keep existing despite the increases in productivity due to economic rents. Every time there is some slack in the system, renters raise their prices and capture the wealth. UBI itself is not enough, but UBI+LVT combo is what will allow to move to a much better equilibrium in our world. In Anoxistan, likewise, there would be needed an Air Value Tax, working by the same Georgist principles to erradicate their brand of poverty.

I was tempted to agree, but on a reflection, no I don't think that it's correct to classify rent-seeking as a work of Moloch.

Classical example of economical facet of Moloch is a capitalist who would love to give their workers a living wage, but doing so would make the product more expensive, therefore leading to being out-competed by those who did not pay their workers decent wages. Optimization leading to the sacrifice of all our other values.

On the other hand a landlord who raises the price of the rent due to a new business opening nearby doesn't do it because otherwise they would be out-competed by the landlords who do. They just do it because they want to earn more and can earn more this way. This is not some complicated game theoretic equilibrium that a landlord is a hostage of. In this case, this is just greed.

And the reasons why landlords can get away with this is because the molochian optimization mechanism selectively does not apply to them! While market forces push the capitalist to make the goods and services as cheap as possible, without LVT, this pressure doesn't exist for the landlord. They are the part of the system that has actual slack. And they can use it to sipho...

As someone coming from a "poor" European immigrant family, I have always found it interesting that in the U.S. people with big cars can be considered poor.

These U.S. people, the "poor" Anoxan and I know that the abundance of something does not mean having the opportunity to live life. Ask King Midas.

An N-fold increase in selected productivity, like in the number of winter socks or the amount of gold you have, does not mean your life opportunities are going to drastically increase allowing you to gain momentum towards an escape velocity from your miserable ...

Many people seem to think the answer to the puzzle posed here is obvious, but they all think it's something different. This has nagged at me since it was posted. It's an issue that more people need to be thinking about, because if we don't understand it we can't fix it, and so the standard approaches to poverty may just fail even as our world becomes richer. Strong upvote for 2024 review.

I think you overstate how wonderful hunter-gatherer life was, even in the good times. No, you didn't have to work 60 hour weeks and suck up to the boss, but you did have to conform to the norms of your tribe or you would find it impossible to get a wife, be shunned by, what was effectively, everyone in existence, or even be cast out to die, alone. Getting on in modern society is much less onerous.

This relates to my favorite question of economics: are graduate students poor or rich? This post suggests an answer I hadn’t thought of before: it depends on the attitudes of the graduate advisor, and almost nothing else.

There are rich people pushing themselves work 60+ hour days struggling to keep a smile on their face while people insult and demean them. And there are poor people who live as happy ascetics, enjoying the company of their fellows and eating simple meals, choosing to work few hours even if it means forgoing many things the middle class would call necessities.

There are more rich people that choose to give up the grind than poor people. It's tougher to accept a specific form of suffering if you see that 90% of your peers are able to solve the suffering with w...

You give the constraints of the middle class worried they'll slip down, not the poorest Americans directly. If 12% of Americans live in poverty, then the example concerns are those of the 12-50th percentiles. You say the lumpen-proletariat will always exist, but prove that the lives of the proletariat won't improve much.

"credentialist colleges that raise their prices to capture more and more of the returns to the credential, until huge portions of the former middle class's early-life earnings" - Explicitly not the poorest.

"Like working 60...

Thanks for this post! I have always been annoyed when on Reddit or even here, the response to poverty always goes back to, "but poor people have cell phones!" It all comes down to freedom -- the amount of meaningfully distinct actions one person can take in the world to accomplish their goals. If there are few real alternatives, and one's best options all involve working until exhaustion, it is not true freedom.

I agree, the poverty restoring equilibrium is more complex than probably UBI -- maybe it's part of Moloch. I think the rents increasing by the UBI ...

[...] somehow humanity's 100-fold productivity increase (since the days of agriculture) didn't eliminate poverty.

That feels to me about as convincing as saying: "Chemical fertilizers have not eliminated hunger, just the other weekend I was stuck on a campus with a broken vending machine."

I mean, sure, both the broken vending machine and actual starvation can be called hunger, just as both working 60h/week to make ends meet or sending your surviving kids into the mines or prostituting them could be called poverty, but the implication that either scour...

What would it be like for people to not be poor?

I reply: You wouldn't see people working 60-hour weeks, at jobs where they have to smile and bear it when their bosses abuse them.

I appreciate the concrete, illustrative examples used in this discussion, but I also want to recognize that they are only the beginnings of a "real" answer to the question of what it would be like to not be poor.

In other words, in an attempt to describe what he sees as poverty, I think Eliezer has taken the strategy of pointing to a few points in Thingspace and saying "here a...

I have known some rich people. They don't act as a coordinated group almost ever; and the group they don't form, is flatly not capable of accurately predicting and deliberately directing world-historical equilibria over centuries.

Beg to differ. Rich people congregate, populate, and settle in areas, and form orgs and egregore that push away and hide the poor and the problems that make them uncomfortable, and this happens largely unconsciously - phenomenologically - yet there is organizational agency in it. And this kind of wealth phenomena has certain...

I think something like this is true:

- For humans, quality of life depends on various inputs.

- Material wealth is one input among many, alongside e.g., genetic predisposition to depression, or other mental health issues.

- Being relatively poor is correlated with having lots of bad inputs, not merely low material wealth.

- Having more money doesn't necessarily let you raise your other inputs to quality of life besides material wealth.

- Therefore, giving poor people money won't necessarily make their quality of life excellent, since they'll often still be deficient in o

It's true that claims that poor people now are much richer than poor or even rich people 300 years ago rely somewhat on cherrypicking which axes to measure, but the cited claims of "100-fold productivity increase" since then *also* rely on cherrypicking which axes to measure.

We haven't gotten 100x more productive in obtaining oxygen, certainly, nor in many still-scarce resources people care about (childcare might be a particularly clear example). So people still experience poverty because civilization is still tightly bottlenecked on some resources.

I don't...

Your writing sounds like someone put you under pressure to finance UBI and combat poverty. I think that’s not good. If they want you to pay for something, then it’s their job to explain to you why it’s ultimately good for you. Of course, in case the difference is too big, they also have the right to cut tie with you — a threat which is only effective if they are doing it better than you or you are doing better in the community with them than outside.

If you are not under pressure but want to hinder others in implementing UBI and combatting poverty, then you...

Independently of the other parts, I like this notion of poverty. I head-chunk the idea as any external thing a person lacks, of which they are struggling to keep the minimum; that is poverty.

This seems very flexible, because it isn't a fixed bar like an income level. It also seems very actionable, because it is asking questions of the object-level reality instead of hand-wavily abstracting everything into money.

Eg, rents in San Francisco would almost instantly rise by the amount of the UBI; no janitors in the Bay Area would be better off as a result.

Side point, but this... doesn't seem to comply with basic supply and demand?

The amount by which the rents would rise would likely depend very heavily on the ratio of price elasticities of supply & demand[1], and in cases where we have neither a perfectly elastic supply[2] nor a perfectly inelastic demand[3], increasing the income of individuals (which could function as, say, an indirect subsidy of sorts...

This is why San Francisco was chosen as the example - at least over the last decade or so it has been one of the most inelastic housing supplies in the U.S.

You are therefore exactly correct: it does not comply with basic supply and demand. This is because basic supply and demand usually do not apply for housing in American cities due to legal constraints on supply, and subsidies for demand.

My rough first attempt at explaining the apparent paradox of poverty continuing to exist despite a ~100x increase in productivity:

Humanity as a whole may have gotten 100x more productive, but most people aren't able to individually contribute 100x more value to the economy (at least not in a way that they are monetarily compensated for). It seems like the increase in productivity largely takes the form of finding more efficient ways to coordinate the efforts of many people (e.g. factories) rather than individuals being able to produce more value on t...

We can imagine two versions of the mysterious-poverty-restoring-force hypothesis:

Weak: Despite changes in overall productivity, poverty persists.

Strong: Despite changes in overall productivity, the proportion of the population in poverty remains constant.

I think weak is almost certainly true, you're right that UBI won't eliminate poverty. But I think strong is likely false - people desperately struggling: people living relatively comfortably, with slack for hobbies and "fun spending" of time and money doesn't seem constant over history.

I suspec...

Where does the Poverty Equilibrium come from? How do its restoring forces act?

I can’t claim to know the answer, but let’s spend a few minutes trying to figure it out.

Let’s stick with Eliezer’s definition of poverty as extreme difficulty accessing the necessities of life. That is, if it’s very hard for you to afford, say, housing, you’re in poverty.

It is not difficulties affording luxuries; just necessities. Obviously this is a little tricky because “necessity” is a spectrum, not a binary (is a school for your kids where they’re safe from violence a lux...

Large groups of people can only live together by forming social hierarchies.

The people at the top of the hierarchy want to maintain their position both for themselves AND for their children (It's a pretty good definition of a good parent).

Fundamentally the problem is that it is not really about resources - It's a zero sum game for status and money is just the main indicator of status in the modern world.

Your Anoxistan argument seems valid as far as it goes - if one critical input is extremely hard to get, you're poor, regardless of whatever else you have.

But that doesn't seem to describe 1st world societies. What's the analog to oxygen?

My sense is that "poor people" in 1st world countries struggle because they don't know how to, or find it culturally difficult to, live within their means. Some combination of culture, family breakdown, and competitive social pressures (to impress potential mates, always a zero-sum game) cause them to live in a fashio...

I feel that one of the key elements of the problem is misplaced anxiety. If the ancient farmer stops working hard he will not not get enough food. So all his family will be dead. In modern Western society, the risk of being dead from not working is nearly zero. (You are way more likely to die from exhausting yourself and working too hard). When someone works too hard, usually it is not fear of dying too earlier, or that kids will die. It is a fear of failure, being the underdog, not doing what you are supposed to, and plenty of other constructs...

Note: there is an AI audio version of this text over here: https://askwhocastsai.substack.com/p/eliezer-yudkowsky-tweet-jul-21-2024

I find the AI narrations offered by askwho generally ok, worse than what a skilled narrator (or team) could do but much better than what I could accomplish.

I honestly don't know if I understand what Eliezer is getting at so might be far off. If the premise is that increased real income (that 100-fold increase) has not really decreased what is undertood as poverty in human existance then income related factors (a UBI) seem definitionally ineffective as well.

But I'm not sure that he is subtly trying to say the whole UBI effort is essentially a fool's errand.

But I'm far from sure that his suggestion is that a UBI, at some level of abundance, can eliminate poverty because all the basic necessities (not sure how one defines that in a world where people do seem to care about relative outcomes over absolute outcomes) are guaranteed.

I began to write a long comment about how to possibly identify poverty-restoring forces, but I think we actually should take a step back and ask:

Why do we care about poverty in the first place?

"The utility function is not up for grabs"

Sure, but poverty seems like a rather complex idea to really be directly in our utility function, instead of instrumentally.

"Well we care about poverty because it causes suffering"

Ok. But why not just talk about reducing suffering then?

"Suffering can have multiple causes. It is helpful to focus on a single c...

So I’ve thought about this very example (or one very similar to it, the increasing price of healthcare per capita which is somewhat a sadly realistic proxy for the Anoxistan thought experiment). But healthcare has gotten really expensive because we now treat things that used to kill people outright (e.g., chemotherapy, stem cells and/or recently invented biologics didn’t even exist before).

Also with regards to working 60 hours a week so your kids can go to a school where their brain doesn’t rot or they don’t lose teeth.. that’s not just unrealistic, it doe...

I agree with the points brought up by aphyer and sunwillrise on working hours, and would like to offer additional thoughts. A friend of mine, when he got his first job, saved until he could last a week on his savings, then a month, and so on. This gave him a buffer he could use to tell a horrible boss to shove it.

These days, phone apps like Stockpile allow one to invest as little as $5 per fractional share of NVDA, AMZN, GOOG, and AAPL, with the help of services like Motley Fool for 25¢/day.

Just as people vote with their feet to get into the U.S., I’m wond...

Brilliant essay. It reminds me of the work of James C. Scott. However, I am quite surprised by the conclusion: "I do not understand the Poverty Equilibrium. So I expect that a Universal Basic Income would fail to eliminate poverty, for reasons I don't fully understand." To me, the explanation of the Poverty Equilibrium is quite simple. Yes, there are diminishing returns in the marginal value of all resources, but there is also an increase in the subjective value of all resources in consideration of what you know others possess. Alice is happy with one bana...

I often use a similar framing to make a point about the relative quality of life of high and low income earners in my city for instance: my household income is in top 5% (maybe 1%) but my life is not significantly different to most. We live in a normal house, commute to work on the train and work normal 9-5 jobs, cook dinner, put kids to bed, wash the dishes, maybe watch some TV. Sure we holiday overseas instead of going caravaning, and live in a nicer (judged by land values) area; but these sorts of things aren't really that important to happiness.

I understand that you are saying that even a single resource lacking for one to "thrive" is poverty, that poor people are not thriving today because they lack some resource that they need to thrive. This resource was not provided to them even after the society became much more productive, and hence probably would not be provided to them if we implement UBI. You try to show this using a counter factual country where the critical resource is oxygen.

I think this is a false equivalence. The 'equilibrium' that enforces poverty is actually people themselves. I t...

The root cause of the problem as I see it is that hierarchies are often based on dominance, exploitation, and power accumulation, rather than moral or epistemic impartiality. This creates a system where trustworthiness is undervalued, and poverty persists. What we need is an accurate instrument to measure trustworthiness. Once we have that, hierarchies will change, the environment will change, and trustworthiness will become the foundation of success. Adoption of the trustwortiness instrument will ultimately eliminate poverty.

UBI strikes me as a much less powerful change than a 100-fold productivity increase.

This statement encapsulates what, IMHO, is the evident shortcoming of the article. UBI is a policy addressing inequality; 100-fold productivity isn't. Poverty is a social construct; inequality is not.

The social construct of poverty is built differently for every niche. The effects of wealth/income distribution directly affect the construction of the concept. Furthermore, it directly affects the health of individuals.

This article made me reflect on the two alternative definitions of poverty. One, relative poverty, and two, what I call lifestyle poverty. The latter being split into ascending levels starting from $2.15 a day (below which you eventually die), with the next level reached at roughly a factor of 4. The factor of 4 making a qualitative difference in lifestyle in a practical non theoretical way.

Relative poverty has a social element which we will probably never escape. But, level 0 poverty below $2.15, also known as absolute poverty is down from 90% before the ...

I do not see what there is in a continued existence of 60-hour weeks that cannot be explained by the relative strength of the income and substitution effects. This doesn’t need to tell us about a poverty equilibrium, it can just tell us about people’s preferences?

it only takes a life lacking in one resource needed to survive, to produce some quality that I think ancient poor people would also recognize as 'poverty'.

Reminds me of Material Deprivation Index metrics for poverty - what needed things can they not afford? - as distinct from standard income-based poverty lines.

But to regard these as a series of isolated accidents is, I think, not warranted by the number of events which they all seem to point in mysteriously a similar direction. My own sense is more that there are strange and immense and terrible forces behind the Poverty Equilibrium.

Reminded me of The Hero With A Thousand Chances

May be societies with less poverty are less competitive

On the whole, however, a UBI strikes me as a much less powerful change than a 100-fold productivity increase. If that didn't prevent a huge underclass that has to desperately scrabble for scraps, I expect UBI can't prevent it either.

This is a system problem.

While the current system of money, property rights, and paid work has been hugely beneficial for many people, it has suffered from a major problem: if you could not earn money (and had no savings or family support)... you were forced into charity, or crime... or you starved and died.

Over the last ...

Yes. Trying to make up a new way to redistribute the products among the whole society is pointless, if the means of production are still owned privately.

Great post! Really. I used to be a picky reader and even if you show me the tweet of a Nobel laureate, I can immediately pick out a few points to criticize, which, of course, doesn’t mean that they aren’t way better than me in economics. A few tweets doesn’t say much about someone’s achievement, if you read my tweets, you can certainly find more to pick on. That you’ve achieved a lot in life, doesn’t even need to be mentioned by me, all know it.

Although I don’t agree with every point in this post, I quite like its philosophical touch, which possibly explai...

The LessWrong Review runs every year to select the posts that have most stood the test of time. This post is not yet eligible for review, but will be at the end of 2025. The top fifty or so posts are featured prominently on the site throughout the year.

Hopefully, the review is better than karma at judging enduring value. If we have accurate prediction markets on the review results, maybe we can have better incentives on LessWrong today. Will this post make the top fifty?

New here. Forgive me. Must confess, feel the sense of emerging from a time warp that transfigured apples to apples, to apples to oxygen, for comparison sake. Not trying to ruffle feathers, step on toes, or be told to kick rocks, barefoot, but….

Oxygen is totally dissimilar to apples, making the task of comparison feel not unlike comparing spaghetti code to moms traditional recipe. Time, availability, space, and more - all dissimilarities of form - both in consumption and regeneration. In the interest of time, and for due consideration, therein, I will ...

You are right to say that money alone is not enough to eliminate poverty, although that’s no sufficient argument to disprove the effectiveness of UBI, because you only distinguish between poverty and no-poverty, but not between more-poverty and less-poverty. I don’t know if UBI can reduce poverty, but if you want to disprove it then you need to say more.

It’s amazing that you addressed various aspects of poverty and not reduced it to more shirts vs fewer shirts, but you somehow mingled everything up so that it’s difficult to see your point. In the story abo...

(Crossposted from Twitter)

I'm skeptical that Universal Basic Income can get rid of grinding poverty, since somehow humanity's 100-fold productivity increase (since the days of agriculture) didn't eliminate poverty.

Some of my friends reply, "What do you mean, poverty is still around? 'Poor' people today, in Western countries, have a lot to legitimately be miserable about, don't get me wrong; but they also have amounts of clothing and fabric that only rich merchants could afford a thousand years ago; they often own more than one pair of shoes; why, they even have cellphones, as not even an emperor of the olden days could have had at any price. They're relatively poor, sure, and they have a lot of things to be legitimately sad about. But in what sense is almost-anyone in a high-tech country 'poor' by the standards of a thousand years earlier? Maybe UBI works the same way; maybe some people are still comparing themselves to the Joneses, and consider themselves relatively poverty-stricken, and in fact have many things to be sad about; but their actual lives are much wealthier and better, such that poor people today would hardly recognize them. UBI is still worth doing, if that's the result; even if, afterwards, many people still self-identify as 'poor'."

Or to sum up their answer: "What do you mean, humanity's 100-fold productivity increase, since the days of agriculture, has managed not to eliminate poverty? What people a thousand years ago used to call 'poverty' has essentially disappeared in the high-tech countries. 'Poor' people no longer starve in winter when their farm's food storage runs out. There's still something we call 'poverty' but that's just because 'poverty' is a moving target, not because there's some real and puzzlingly persistent form of misery that resisted all economic growth, and would also resist redistribution via UBI."

And this is a sensible question; but let me try out a new answer to it.

Consider the imaginary society of Anoxistan, in which every citizen who can't afford better lives in a government-provided 1,000 square-meter apartment; which the government can afford to provide as a fallback, because building skyscrapers is legal in Anoxistan. Anoxistan has free high-quality food (not fast food made of mostly seed oils) available to every citizen, if anyone ever runs out of money to pay for better. Cities offer free public transit including self-driving cars; Anoxistan has averted that part of the specter of modern poverty in our own world, which is somebody's car constantly breaking down (that they need to get to work and their children's school).

As measured on our own scale, everyone in Anoxistan has enough healthy food, enough living space, heat in winter and cold in summer, huge closets full of clothing, and potable water from faucets at a price that most people don't bother tracking.

Is it possible that most people in Anoxistan are poor?

My (quite sensible and reasonable) friends, I think, on encountering this initial segment of this parable, mentally autocomplete it with the possibility that maybe there's some billionaires in Anoxistan whose frequently televised mansions make everyone else feel poor, because most people only have 1,000-meter houses.

But actually this story has a completely different twist! You see, I only spoke of food, clothing, housing, water, transit, heat and A/C. I didn't say whether everyone in Anoxistan had enough air to breathe.

In Anoxistan, you see, the planetary atmosphere is mostly carbon dioxide, and breathable oxygen (O2) is a precious commodity. Almost everyone has to wear respirators at all times; only the 1% can afford to have a whole house full of breathable air, with some oxygen leaking away despite the best seals.

And while Anoxistan does have a prosperous middle class -- which only needs to work 40-hour weeks in order to get enough oxygen to live -- there's also a sizable underclass which has to work 60-hour weeks to get that much oxygen.

These relatively oxygen-poorer Anoxians submit to horrible bosses at horrible jobs and endure all manner of abuse, to earn enough oxygen to live. They never go on hikes in Nature or otherwise 'exercise', because they can't afford that amount of physical exertion; they can't afford to convert that much O2 to CO2.

They try to take shallow breaths, the Anoxians who have a kid; to make sure their own kid has enough to breathe, and grows up without too much anoxia-induced brain damage.

And if you showed one of the Anoxians a hunter-gatherer from our world, living in what my sensible friends really would consider poverty -- somebody who has 0 or 1 foot-wrappings, no car, no cellphone, no Internet access -- the Anoxian would be breathless at the unimaginable wealth of oxygen this hunter-gather commands. They can walk around in a planet of oxygen free for the breathing! They can just go running anytime they like, without having to save up for it! They can have kids without asking themselves what their kids are going to breathe!

As for the hunter-gatherer's paucity of fabric, the absence of closets full of clothes or indeed housing at all, the Anoxians hardly notice that part -- everyone on their planet has enough clothes in their closet, so few people there much remark on it or notice; any more than we on Earth ask whether people have enough to breathe.

What's my point here?

That it only takes a life lacking in one resource needed to survive, to produce some quality that I think ancient poor people would also recognize as 'poverty'.

It's the quality of working yourself until you can't work any longer; of taking on jobs that are painful to do, and require groveling submission to bosses, because that's what it takes to get the few scraps to hang on.

Does owning more than one pair of shoes, as would once have been a sign of great wealth, alter that or change that? Well, it can be convenient to own different pairs of shoes for different pedalic situations. But the amount that shoes contribute to welfare, soon saturates –

– just like your whole planet full of oxygen doesn't mean you live in an unimaginably wealthy society. Once you have enough oxygen to get by, the value of more oxygen than that, quickly saturates and asymptotes. Having 10 times as much oxygen than that, won't make up for not having enough food to eat in wintertime, or not being able to afford healthy-enough food not to wreck your body.

The marginal value of more oxygen saturates, and can't cover all aspects of life in any case; which is to say:

Even enough oxygen to make you an Anoxan decamillionaire, won't stop you from being poor.

I think this is the problem with saying that modern society can't have real poor people, because they own an amount of clothing and fabric that would've once put somebody well into the realm of nobility, back when women spent most of their days stretching wool with a distaff in order to let anyone have clothes at all. That amount of fabric doesn't mean you can't be poor, just like having vast amounts of oxygen in your apartment doesn't rule out poverty. It means that a resource which was once very expensive, like fabric in medieval Europe or oxygen in Anoxistan, has become cheap enough not to mention.

And that is an improvement, compared to the counterfactual! I'm glad I don't have to constantly worry about running out of clothing or oxygen! It is legitimately a better planet, compared to the counterfactual planet where life has all of our current problems plus not enough oxygen!

But if you agree that medieval peasants or hunter-gatherers can be poor, you are acknowledging that no amount of oxygen can stop somebody from being poor.

Then fabric can be the same way: there can be no possible sufficiency of clothing in your closet that rules out poverty, even though somebody with plenty of clothing is counterfactually better off compared to somebody who owns only one shirt.

The sum of every resource like that could rule out poverty, if you had enough of all of it. What would be the sign of this state of affairs having come to hold? What would it be like for people to not be poor?

I reply: You wouldn't see people working 60-hour weeks, at jobs where they have to smile and bear it when their bosses abuse them.

When a poor Anoxan looks at a hunter-gatherer of Earth -- especially if they're looking at someone from a time before hunter-gatherers got pushed off all the good land, and looking at an adult male -- I think the poor Anoxan legitimately recognizes this hunter-gatherer as being an important sense less like a 'poor person' like themselves. Hunter-gatherers die during famine years, which enforces the local Malthusian equilibrium; but at other times can get by on hunting for 4 hours per day, and at no point have to bow and scrape to live.

Or if the bowing and scraping doesn't strike you as particularly horrible, and you want to know what it is that modern 'poor people' really need to work 60 hours to accomplish, if not having unnecessary amounts of fabric -- well, what about working that hard to expose your children to less permanent damage, like an Anoxan taking shallow breaths themselves, to try to have their children end up with less hypoxic brain damage during formative years? Like working 60-hour weeks to afford rent somewhere the school districts will damage your child less -- where the violence is at a low-enough level that your child keeps most of their teeth. That's also what I'd call poverty, a recognizable state of desperate scrabbling for scraps.

I think this is what people are hoping Universal Basic Income will finally eliminate.

So -- having hopefully now established that there is any general bad quality of life apart from owning a too-small number of shirts, which somehow persisted through a 100-fold increase in productivity since the days of medieval cities -- we can ask:

Will a Universal Basic Income finally be enough to eliminate the state of life I'd call 'poverty'?

And my current reply is that I'm skeptical that UBI will finally be the thing that does it.

If you went back in time to the age of peasant farmers and told them that farming and most manufacture had become 100 times more productive, they might fondly imagine that you wouldn't have poor people any more -- that there would be no more people in the recognizable state of "desperately scrabbling for scraps".

And yet somehow there is a Poverty Equilibrium which beat a 100-fold increase in productivity plus everything else that went right over the last thousand years.

We can point at lots of particular historical developments that play a role in the current situation.

Eg, high-tech societies imposing artificial obstacles to housing or babysitting. Eg, credentialist colleges that raise their prices to capture more and more of the returns to the credential, until huge portions of the former middle class's early-life earnings (as once might have been used to raise children) are going to pay off student loans instead.

But to regard these as a series of isolated accidents is, I think, not warranted by the number of events which they all seem to point in mysteriously a similar direction. My own sense is more that there are strange and immense and terrible forces behind the Poverty Equilibrium.

(No, it's not a conspiracy of rich people, such as some people fondly imagine are solely and purposefully responsible for all the world's awfulness. I have known some rich people. They don't act as a coordinated group almost ever; and the group they don't form, is flatly not capable of accurately predicting and deliberately directing world-historical equilibria over centuries.)

I do not understand the Poverty Equilibrium. So I expect that a Universal Basic Income would fail to eliminate poverty, for reasons I don't fully understand.

I can guess some parts of the story, parts that are relatively easier for me to guess. Eg, rents in San Francisco would almost instantly rise by the amount of the UBI; no janitors in the Bay Area would be better off as a result. Eg, in 2014 the city of Ferguson, Missouri, which you may remember from the news, issued 2.2 arrest warrants per adult; maybe the Ferguson police departments of the world, just raise their annual quota for fines per capita by the per capita UBI. Eg, governments have always taken the existence of wealth as a license to pass regulations that destroy wealth; many different parts of government would take "poor people have more money" as a license to impose more costs on them.

But none of that quite sums up to a vast pressure that somehow works to the end of making sure that people go on being poor. That's what I think held historically; so in the future I'd expect a strange vast pressure to somehow not have Universal Basic Income play out as its advocates hope.

And also to be clear: it's quite possible that tomorrow's poor people do finally end up somewhat better off, because of Universal Basic Income, than they would have been counterfactually otherwise. The forces that maintain the Poverty Equilibrium don't actually prevent the people working to exhaustion under horrible bosses, from also having multiple sets of clothing and clean water. People who have that genuinely are better off, even if they're still working to exhaustion; just like medieval peasants are counterfactually better off for having plenty of oxygen.

(I do worry a bit that Universal Basic Income is the sort of essentially financial engineering which will prove unable to help at all in the face of the mysterious porverty-restoring forces, since it's not itself a water faucet or a loom. But financial engineering could help temporarily, until the Ferguson police department catches up and issues more fines; and, I sadly suppose, long-run restoring forces don't actually matter if superintelligence is going to omnicide everyone etcetera. But I don' t know how else to participate in conversations like this one, except under the supposition that there's an international treaty banning advanced AI, such that long-run outcomes go on actually existing.)

To sum up: I don't quite know what would actually happen, with UBI practiced on a scale where large-scale Poverty-Restoring forces would have a chance to catch up; because I do not have an account of history that explains why the Poverty-Restoring forces already had the power they did.

On the whole, however, a UBI strikes me as a much less powerful change than a 100-fold productivity increase. If that didn't prevent a huge underclass that has to desperately scrabble for scraps, I expect UBI can't prevent it either.

It's the sort of thing where, in a better world, one would call for more economics research and more economist attention to questions like "Where does the Poverty Equilibrium come from? How do its restoring forces act?"

But before any project like that could get started, you'd first have to answer the immediate reply that every economist and my sensible friends always give me, whenever I try to pose the question: "What do you mean, there's a 'Poverty Equilibrium' that resisted all our past productivity improvements? The people we call 'poor' today own more than one shirt; we only consider them poor by comparison to people even richer than that."

And to this my attempt at a snappy answer – to summarize the discussion above – is here: