Minor note: I think we should probably avoid using the term "RSP" to refer to the broad class of things. I would prefer "voluntary safety commitments" or something like that.

RSP is both a bad name IMO (it has "responsible" in the name, whereas whether the scaling is actually "responsible" is something for people & governments to evaluate) and also gets a little confusing because Anthropic's doc is called an RSP.

I like "voluntary safety commitments" as the broad class of things, and then you can use the company-specific terminology when referring to the company's particular flavor (RSP for Anthropic, PF for OpenAI, etc.)

My only concern with "voluntary safety commitments" is that it seems to encompass too much, when the RSPs in question here are a pretty specific framework with unique strengths I wouldn't want overlooked.

I've been using "iterated scaling policy," but I don't think that's perfect. Maybe "evaluation-based scaling policy"? or "tiered scaling policy"? Maybe even "risk-informed scaling policy"?

a pretty specific framework with unique strengths I wouldn't want overlooked.

What are some of the unique strengths of the framework that you think might get overlooked if we go with something more like "voluntary safety commitments" or "voluntary scaling commitments"?

(Ex: It seems plausible to me that you want to keep the word "scaling" in, since there are lots of safety commitments that could plausibly have nothing to do with future models, and "scaling" sort of forces you to think about what's going to happen as models get more powerful.)

Things that distinguish an "RSP" or "RSP-type commitment" for me (though as with most concepts, something could lack a few of the items below and still overall seem like an "RSP" or a "draft aiming to eventually be an RSP")

- Scaling commitments: Commitments are not just about deployment but about creating/containing/scaling a model in the first place (in fact for most RSPs I think the scaling/containment commitments are the focus, much more so than the deployment commitments which are usually a bit vague and to-be-determined)

- Red lines: The commitment spells out red lines in advance where even creating a model past that line would be unsafe given their current practices/security/alignment research, likely including some red lines where the developer admits they do not know how to ensure safety anymore, and commits to not reaching that point until the situation changes.

- Iterative policy updates: For red-lines where the developer doesn't know what exact mitigations would be sufficient to ensure safety, they identify a previous point where they do think they can mitigate risks, and commit to not scaling further than that until they have published a new commitment and given the public a chance to scrutinize it

- Evaluations and accountability: I think this is an area that many RSPs do poorly at, where the developer presents clear externally accountable evidence that:

- They will not suddenly cross any of their red lines before the mitigations are implemented/a new RSP version has been published and given scrutiny, by pointing at specific evaluations procedures and policies

- Their mitigations/procedures/evaluations etc. will be implemented faithfully and in the spirit of the document, e.g. through audits/external oversight/whistleblowing etc.

Voluntary commitments that wouldn't be RSPs:

-

We commit to various deployment mitigations, incident sharing etc. (these are not about scaling)

-

We commit to [amazing set of safety practices, including state-proof security and massive spending on alignment etc.] by 2026 (this would be amazing, but doesn't identify red lines for when those mitigations would no longer be enough, and doesn't make any commitment about what they would do if they hit concerning capabilities before 2026)

... many more obviously, I think RSPs are actually quite specific.

This seems like a solid list. Scaling certainly seems core to the RSP concept.

IMO "red lines, iterative policy updates, and evaluations & accountability" are sort of pointing at the same thing. Roughly something like "we promise not to cross X red line until we have published Y new policy and allowed the public to scrutinize it for Z amount of time."

One interesting thing here is that none of the current RSPs meet this standard. I suppose the closest is Anthropic's, where they say they won't scale to ASL-4 until they publish a new RSP (this would cover "red line" but I don't believe they commit to giving the public a chance to scrutinize it, so it would only partially meet "iterative policy updates" and wouldn't meet "evaluations and accountability.")

They will not suddenly cross any of their red lines before the mitigations are implemented/a new RSP version has been published and given scrutiny, by pointing at specific evaluations procedures and policies

This seems like the meat of an ideal RSP. I don't think it's done by any of the existing voluntary scaling commitments. All of them have this flavor of "our company leadership will determine when the mitigations are sufficient, and we do not commit to telling you what our reasoning is." OpenAI's PF probably comes the closest, IMO (e.g., leadership will evaluate if the mitigations have moved the model from the stuff described in the "critical risk" category to the stuff described in the "high risk" category.)

As long as the voluntary scaling commitments end up having this flavor of "leadership will make a judgment call based on its best reasoning", it feels like the commitments lack most of the "teeth" of the kind of RSP you describe.

(So back to the original point– I think we could say that something is only an RSP if it has the "we won't cross this red line until we give you a new policy and let you scrutinize it and also tell you how we're going to reason about when our mitigations are sufficient" property, but then none of the existing commitments would qualify as RSPs. If we loosen the definition, then I think we just go back to "these are voluntary commitments that have to do with scaling & how the lab is thinking about risks from scaling.")

Yeah, I think you're kind of right about why scaling seems like a relevant term here. I really like that RSPs are explicit about different tiers of models posing different tiers of risks. I think larger models are just likely to be more dangerous, and dangerous in new and different ways, than the models we have today. And that the safety mitigations that apply to them need to be more rigorous than what we have today. As an example, this framework naturally captures the distinction between "open-sourcing is great today" and "open-sourcing might be very dangerous tomorrow," which is roughly something I believe.

But in the end, I don't actually care what the name is, I just care that there is a specific name for this relatively specific framework to distinguish it from all the other possibilities in the space of voluntary policies. That includes newer and better policies — i.e. even if you are skeptical of the value of RSPs, I think you should be in favor of a specific name for it so you can distinguish it from other, future voluntary safety policies that you are more supportive of.

I do dislike that "responsible" might come off as implying that these policies are sufficient, or that scaling is now safe. I could see "risk-informed" having the same issue, which is why "iterated/tiered scaling policy" seems a bit better to me.

even if you are skeptical of the value of RSPs, I think you should be in favor of a specific name for it so you can distinguish it from other, future voluntary safety policies that you are more supportive of

This is a great point– consider me convinced. Interestingly, it's hard for me to really precisely define the things that make something an RSP as opposed to a different type of safety commitment, but there are some patterns in the existing RSP/PF/FSF that do seem to put them in a broader family. (Ex: Strong focus on model evaluations, implicit assumption that AI development should continue until/unless evidence of danger is found, implicit assumption that company executives will decide once safeguards are sufficient).

Quoting me from last time you said this:

The label "RSP" isn't perfect but it's kinda established now. My friends all call things like this "RSPs." . . . I predict change in terminology will happen ~iff it's attempted by METR or multiple frontier labs together. For now, I claim we should debate terminology occasionally but follow standard usage when trying to actually communicate.

I don't think the term is established, except within a small circle of EA/AIS people. The vast majority of policymakers do not know what RSPs are– they do know what "voluntary commitments" are.

(We might just disagree here, doesn't seem like it's worth a big back-and-forth.)

Commentary on the content of the commitments: shrug. Good RSPs are great but probably require the right spirit to be implemented well, and most of these companies don't employ people who work on scalable alignment, evaluating dangerous capabilities, etc. And people have mostly failed to evaluate existing RSP-ish plans well; if a company makes a basically meaningless RSP, people might not notice.

Strong agree. I mostly see these commitments as useful foundations for domestic and international regulation. If the government is checking or evaluating these criteria, they matter. If not, it seems very easy for companies to produce nice-sounding documents that don't contain meaningful safety plans (see also affirmative safety, safety cases).

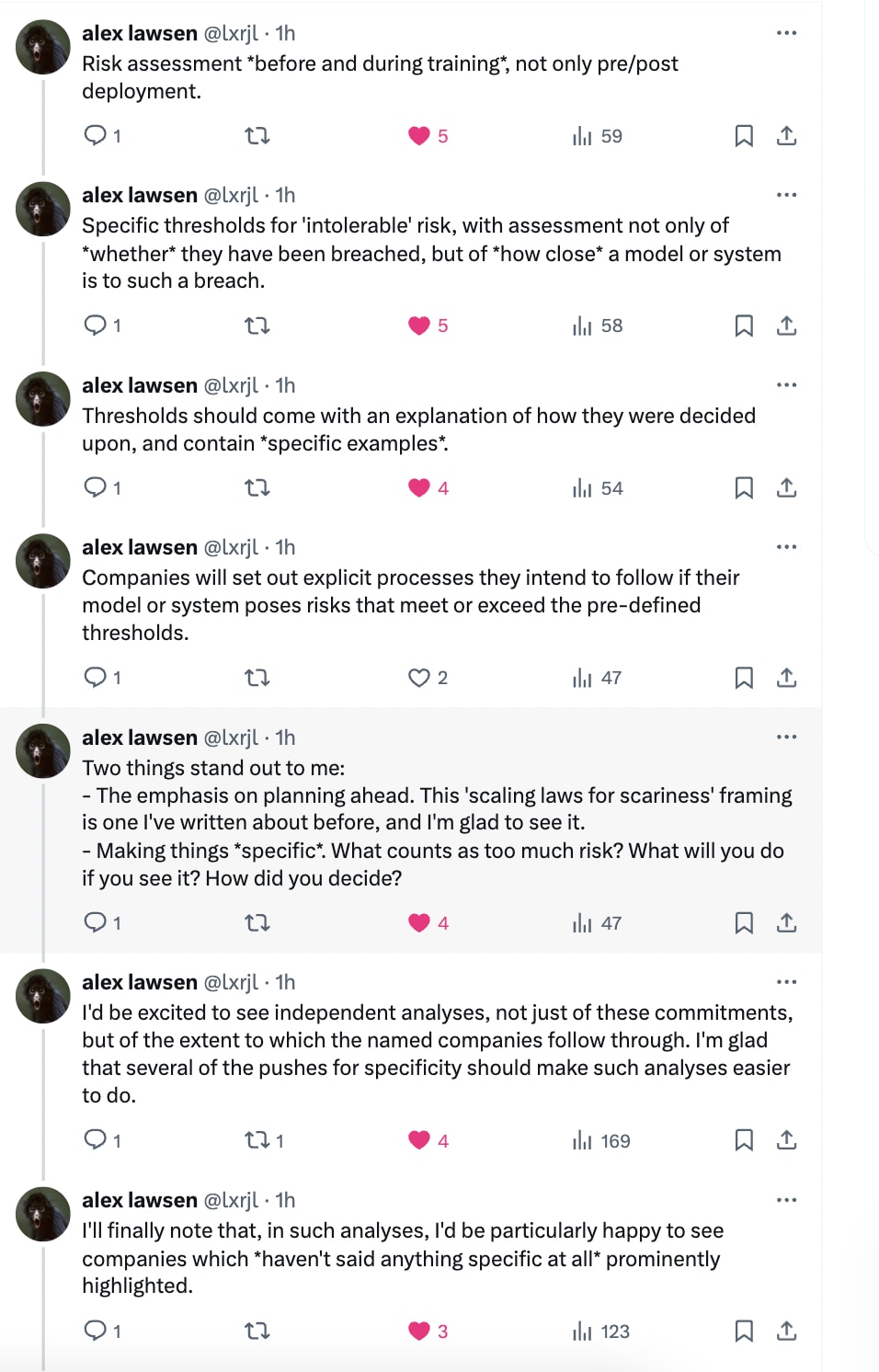

With that in mind, Alex Lawsen (on X) noticed some good things about the specifics of the commitments:

If you go with an assumption of good faith then the partial, gappy RSPs we've seen are still a major step towards having a functional internal policy to not develop dangerous AI systems because you'll assume the gaps will be filled in due course. However, if we don't assume a good faith commitment to implement a functional version of what's suggested in a preliminary RSP without some kind of external pressure, then they might not be worth much more than the paper they're printed on.

But, even if the RSPs aren't drafted in good faith and the companies don't have a strong safety culture (which seems to be true of OpenAI judging by what Jan Leike said), you can still have the RSP commitment rule be a foundation for actually effective policies down the line.

For comparison, if a lot of dodgy water companies sign on to a 'voluntary compact' to develop some sort of plan to assess the risk of sewage spills then probably the risk is reduced by a bit, but it also makes it easier to develop better requirements later, for example by saying "Our new requirement is the same as last years but now you must publish your risk assessment results openly" and daring them to back out. You can encourage them to compete on PR by making their commitments more comprehensive than their opponents and create a virtuous cycle, and it probably just draws more attention to the plans than there was before.

You can still have the RSP commitment rule be a foundation for actually effective policies down the line

+1. I do think it's worth noting, though, that RSPs might not be a sensible foundation for effective policies.

One of my colleagues recently mentioned that the voluntary commitments from labs are much weaker than some of the things that the G7 Hiroshima Process has been working on.

More tangibly, it's quite plausible to me that policymakers who think about AI risks from first principles would produce things that are better and stronger than "codify RSPs." Some thoughts:

- It's plausible to me that when the RSP concept was first being developed, it was a meaningful improvement on the status quo, but the Overton Window & awareness of AI risk has moved a lot since then.

- It's plausible to me that RSPs set a useful "floor"– like hey this is the bare minimum.

- It's plausible to me that RSPs are useful for raising awareness about risk– like hey look, OpenAI and Anthropic are acknowledging that models might soon have dangerous CBRN capabilities.

But there are a lot of implicit assumptions in the RSP frame like "we need to have empirical evidence of risk before we do anything" (as opposed to an affirmative safety frame), "we just need to make sure we implement the right safeguards once things get dangerous" (as opposed to a frame that recognizes we might not have time to develop such safeguards once we have clear evidence of danger), and "AI development should roughly continue as planned" (as opposed to a frame that considers alternative models, like public-private partnerships).

More concretely, I would rather see policy based on things like the recent Bengio paper than RSPs. Examples:

Despite evaluations, we cannot consider coming powerful frontier AI systems “safe unless proven unsafe.” With present testing methodologies, issues can easily be missed. Additionally, it is unclear whether governments can quickly build the immense expertise needed for reliable technical evaluations of AI capabilities and societal-scale risks. Given this, developers of frontier AI should carry the burden of proof to demonstrate that their plans keep risks within acceptable limits. By doing so, they would follow best practices for risk management from industries, such as aviation, medical devices, and defense software, in which companies make safety cases

Commensurate mitigations are needed for exceptionally capable future AI systems, such as autonomous systems that could circumvent human control. Governments must be prepared to license their development, restrict their autonomy in key societal roles, halt their development and deployment in response to worrying capabilities, mandate access controls, and require information security measures robust to state-level hackers until adequate protections are ready. Governments should build these capacities now.

Sometimes advocates of RSPs say "these are things that are compatible with RSPs", but overall I have not seen RSPs/PFs/FSFs that are nearly this clear about the risks, this clear about the limitations of model evaluations, or this clear about the need for tangible regulations.

I've feared previously (and continue to fear) that there are some motte-and-bailey dynamics at play with RSPs, where proponents of RSPs say privately (and to safety people) that RSPs are meant to have strong commitments and inspire strong regulation, but then in practice the RSPs are very weak and end up conveying and overly-rosy picture to policymakers.

One of my colleagues recently mentioned that the voluntary commitments from labs are much weaker than some of the things that the G7 Hiroshima Process has been working on.

Are you able to say more about this?

Thanks for this analysis - I found it quite helpful and mostly agree with your conclusions.

Looking at the list of companies who signed the commitments, I wonder why Baidu isn't on there. Seems very important to have China be part of the discussion, which, AFAIK, mainly means Baidu.

Good point. Just checked - here's the ranking of Chinese LLMs among the top 20:

7. Yi-Large (01 AI)

12. Qwen-Max-0428 (Alibaba)

15. GLM-4-0116 (Zhipu AI)

16. Qwen1.5-110B-Chat (Alibaba)

19. Qwen1.5-72B-chat (Alibaba)

Of the three, only Zhipu signed the agreement.

Google and Anthropic are doing good risk assessment for dangerous capabilities.

My guess is that the current level of evaluations at Google and Anthropic isn't terrible, but could be massively improved.

- Elicitation isn't well specified and there isn't an established science.

- Let alone reliable projections about the state of elicitation in a few years.

- We have a tiny number of different task in these evaluations suites and no readily available mechanism for noticing the models are very good at specific subcategories or tasks in ways which are concerning.

- I had some specific minor to moderate level issues with the Google DC evals suite. Edit: I discuss my issues with the evals suite here.

Basically the companies commit to make responsible scaling policies.

Part of me says this is amazing, the best possible commitment short of all committing to a specific RSP. It's certainly more real than almost all other possible kinds of commitments. But as far as I can tell, people pay almost no attention to what RSP-ish documents (Anthropic, OpenAI, Google) actually say and whether the companies are following them.[1] The discourse is more like "Anthropic, OpenAI, and Google have safety plans and other companies don't." Hopefully that will change.

Maybe "These commitments represent a crucial and historic step forward for international AI governance." It does seem nice from an international-governance perspective that Mistral AI, TII (the Falcon people), and a Chinese company joined.

Full document:

Quick comments on which companies are already complying with each paragraph (off the top of my head; based on public information; additions/corrections welcome):

I. Risk assessment

II. Thresholds

III. Mitigations

IV. Processes if risks reach thresholds

V. [Too meta to evaluate]

VI. [Too meta to evaluate]

VII. "Provide public transparency on the implementation of the above" + "share more detailed information which cannot be shared publicly with trusted actors"

VIII. "Explain how, if at all, external actors, such as governments, civil society, academics, and the public are involved in the process of assessing the risks of their AI models and systems, the adequacy of their safety framework (as described under I-VI), and their adherence to that framework"

Note that the above doesn't capture where the thresholds are and whether the mitigations are sufficient. These aspects of an RSP are absolutely crucial. But they’re hard to evaluate or set commitments about.

Commentary on the content of the commitments: shrug. Good RSPs are great but probably require the right spirit to be implemented well, and most of these companies don't employ people who work on scalable alignment, evaluating dangerous capabilities, etc. And people have mostly failed to evaluate existing RSP-ish plans well; if a company makes a basically meaningless RSP, people might not notice. Sad to see no mention of scheming, alignment, and control. Sad to see nothing on internal deployment; maybe lots of risk comes from the lab using AIs internally to do AI development.

Some of my takes:

- OpenAI's "Preparedness Framework" is insufficient (and OpenAI is not yet complying with it; see this post)

- DeepMind's "Frontier Safety Framework" is weak and unambitious