The way this topic appears to me is that there are different tasks or considerations that require different levels of conscientiousness for the optimal solution. In this frame, one should just always apply the appropriate level of conscientiousness in every context, and the trait conscientiousness is just a bias people have in one direction or the other that one should try to eliminate.

This frame is useful, because it opens up the possibility to do things like "assess required conscientiousness for task", "become aware of bias", "reduce bias", etc. But it may also be wrong in an important way. It's somewhere between difficult to impossible to tell how much conscientiousness is required in any particular case, what's more, even what constitutes an optimal solution may not be obvious. In this frame, trait conscientiousness is not bias, but diversity that nature threw against the problem to do selection with.

I have trouble understanding why, in this case, everyone would need to have a consistently high or consistently low level of it across a wide range of contexts; and why, for example, one can't just try a range of approaches of varying consientiousness levels and learn to optimize from the experience. It isn't necessary in any of the examples above to have a person involved with consistently low levels of it, just a person who in that particular case takes the low-conscientiousness approach. This way we could still fall back on the interpretation as a bias and blame nature for just being inefficient doing the evolution biologically instead of memetically.

Most people who hire practice psychographic nepotism — hiring people with personality traits like their own to do things like they do. Since those people are almost always managers, you get conscientiousness all the way down unless there’s some kind of Human Resources black swan event.

Of course, it will depend to some extent on the job what traits are more beneficial. But what I rarely see are mangers who say “I want to hire someone that complements my skill set.” For example, conscientiousness doesn’t seem to be correlated with innovation at the group level, so why add more of it unless your hiring someone to do routine things well. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1069397111409124

I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s possible with all Big 5 traits to practice being more of the opposite of whatever your trait is and adopt it on an as-beneficial basis (e.g. have an extroverted person be more introverted or an agreeable person be more disagreeable in circumstances where one is the better strategy).

That may be a strategy worth trying. I’ve never asked a high-conscientious person “Could you try coming to work looking a bit more disheveled? Try to stay out of Excel unless it’s really really really important. Ohh and leave some crumbs and an empty soda can on your desk when you go home for the day.”

Easy to find possible evolutionary advantages in many traits, but often a simpler story fits just as well: random imperfection & variation. Here maybe too!

Some people are much less pretty than others (say, judged by the opinion of most). Any advantage from this diversity? Straightforward explanation (although diversity-benefit stories might easily be found too): it may just be variation, despite the regularly even very large costs to those on the lower tail of the distribution. Evolution would clearly like to get it right for us, but sometimes just doesn't hit it quite so well. When considering genetic disabilities, skin problems, or so, this would probably be even more obviously the main explanation.

In analogy to the prettiness example, it seems only natural for there to be (even quite strong) variation around that optimum along the conscientiousness axis.

Psychological character traits are in each new human very subtly impacted by re-mixed genes and by experience; that variance is relatively large need not surprise. Moreover, evolution has very messily and with limited time at disposal shaped homo sapiens' psychology, within an ever changing social and natural environment, and with interaction effects between different traits of which I guess many may have evolved rapidly in different phases, suggesting quite different levels of conscientiousness may have been useful at different places and times overall. Even if lower variance would be attainable after many millions of years of steady evolutionary pressure on a large interconnected population, our recent past, which has shaped our modern brain, has not had anything near that*.

In sum: not so sure we need to involve a story of evolution to have purposely selected some diversity here. It's not impossible, but the principle of parsimony suggests: a bit like for so many of our character traits, large observed variability seems plausible also without special story.

*I once called this "Ad Hoc Evolutionary Adaptation" (though I believe the concept per se is not as new as I thought back then).

I divide my officers into four classes as follows: the clever, the industrious, the lazy, and the stupid. Each officer always possesses two of these qualities. Those who are clever and industrious I appoint to the General Staff. Use can under certain circumstances be made of those who are stupid and lazy. The man who is clever and lazy qualifies for the highest leadership posts. He has the requisite and the mental clarity for difficult decisions. But whoever is stupid and industrious must be got rid of, for he is too dangerous.

-- Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord 1878–1943, German general; possibly apocryphal

I've purposefully worked with smart-but-low-conscientious people on a few projects because I've found they'll come up with "lazy" but workable solutions for problems I would've approached with, "apply more grit." They also benefited, because I will sometimes course-correct when their "lazy" solution is simply not workable. The result was greater efficiency for both of us. This is merely anecdata, though, and I wonder if this holds up in other cases.

This may be an obvious point, but low-conscientiousness people can freeride on the high-conscientiousness ones. Which is advantageous to the former.

And as to why some (but not all) are highly conscientious, maybe it's down to the evolutionary psychology explanation for why some, but only some, people are obsessive checkers (an example of high conscientiousness): because in a prehistoric group, it's beneficial for one or two people to be inclined to e.g. check there are no tigers around, but there's little further value in everyone else doing so, and lots of lost value in other uses of their time.

Also, low conscientiousness (e.g. laziness) in males is seen as unattractive by females, but as long as there are females who are unattractive for other reasons, presumably the latter will pair up with the former anyway for lack of available alternatives. So the laziness reproduces.

There's also a signaling explanation here. Low conscientiousness is only seen as unattractive when you're not good enough to pull it off. It's not cool to fail out of school because you were lazy, but it's cool to ace everything despite barely studying. So you get three groups of people,

- The Actually Amazing - They are just better than everyone else and effortlessly excel. Very rare.

- The Oxonian - They pretend everything comes to them naturally, but they secretly stay up late working.

- The Grifter - Instead of faking the effortlessness, they fake the success.

all of whom look similar from the outside.

Tangential, but as talented people self-select into roles and social groups that match their talents, they find that they have to work harder to maintain the same level of relative success they had earlier in their lives. As such, the Actually Amazing who find it too painful to lose their status usually grow into Oxonians or Grifters.

I like this analysis a lot. BTW there’s a word for the effect of Oxonian behaviour: sprezzatura - meaning apparently nonchalant, effortless ability obtained by extensive secret practice. This was considered desirable among 16th century Italian courtiers:

“The ideal courtier was supposed to be skilled in arms and in athletic events but be equally skilled in music and dancing. However, the courtier who had sprezzatura managed to make these difficult tasks look easy – and, more to the point, not appear calculating, a not-to-be-discounted asset in a milieu commonly informed by ambition, intrigue, etc.”

As long as we're going off on tangents, does anyone know a name for the bias where Oxonians look like they're doing things effortlessly?

I suspect the following is a common psychological failure mode, and I want a term to refer to it:

- See someone doing something amazing and making it look easy

- Try to do something similar (or imagine trying to)

- Realize (or assume) that it's hard and will take a lot of work

- Conclude that because it's easy for the other person and hard for you, you must be bad at it (when actually it's hard for the other person too, but you just don't see the work that they put into it)

- Since you've concluded that it's hard and you're bad at it, you give up

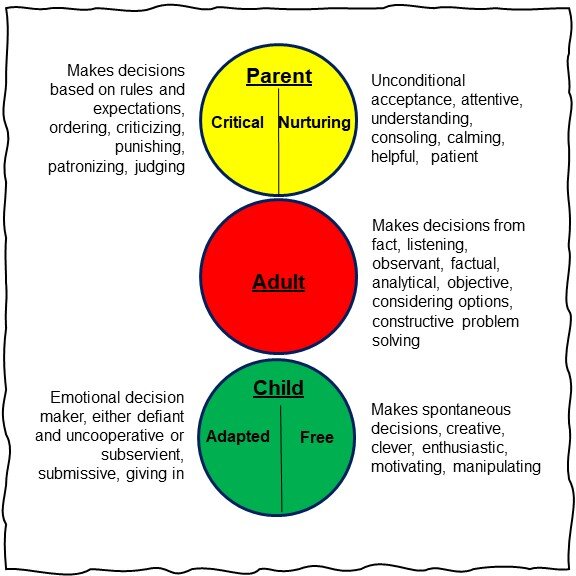

On the topic of how to make yourself attractive to women if you a low-conscientiousness man who would like to be—watch the film Big and read a bit about transactional analysis.** Big is all about how someone who is naturally in the free child ego state (because he's a child) functions in an audit world, and the answer is surprising well (it's fiction, there's a high level of verisimilitude for it's time). Most of the work-world, most of the time, is in critical parent (especially during the current culture war era) or adapted child, and very very rarely in the good states -- adult or free child. Be like Josh in the beginning of the movie (not towards the end where he sells out and gets all critical parent and then is like "oh shit, I need to go back to free child because that was way better.")

** This is advice coming from a Xennial, and I get them impression there may be a generation gap here, so everything may be different now. But I have a hunch this would still work. You may also need some amount of openness to experience to make this happen (if you're reading LessWrong, you probably have that). Also assuming I'm talking to another straight male, and apologies if I'm wrong there.

If I'm right about the generational gap, let drop some other avuncular advice here:

Low-conscientiousness doesn't sentence you fail at school or other things, it just means you have to make a heroic effort at times to be disciplined when you need to be. Don't fight it when you need to do it, just realize you need to do it now, but that you don't need to do it all the time.

High-conscientiousness people will have an advantage in school, for sure, because it's all about being busy doing what you're told to do. At some point in life when people aren't giving them specific directions, their high-conscientiousness will stop being a super power and low-conscientiousness people will have a chance to "catch up." Until then you need to muddle through, graduate, then find a job where it behooves you to be creative.

Three Virtues

According to Larry Wall(1), the original author of the Perl programming language, there are three great virtues of a programmer; Laziness, Impatience and Hubris

Laziness: The quality that makes you go to great effort to reduce overall energy expenditure. It makes you write labor-saving programs that other people will find useful and document what you wrote so you don't have to answer so many questions about it. Impatience: The anger you feel when the computer is being lazy. This makes you write programs that don't just react to your needs, but actually anticipate them. Or at least pretend to. Hubris: The quality that makes you write (and maintain) programs that other people won't want to say bad things about.

I will always choose a lazy person to do a difficult job because a lazy person will find an easy way to do it.

-- Frank B. Gilbreath Sr

"There is nothing so useless as doing efficiently what should not be done at all." - Peter Drucker

I am also someone with very low conscientiousness scores, around 20th percentile, and I've been not sure what to make of it. So I appreciate this post, some food for thought,

[Apologies in advance if I sound like I'm over-generalizing high-conscientiousness or low-conscientiousness people. This is mostly from my own experience, so I'm sure I'm wrong on some counts and may, in fact, be over-generalizing at times. Ohh, and also apologies to Mick Jaggar.]

Please allow me to introduce myself. I'm a man of mess and wile. I've been scoring around 20% (in trait conscientiousness on Big Five tests) for a long, long year, cut by many a sharp wire’s height.

At first glance, conscientiousness as a construct seems a bit like intelligence, in the sense that it would seem everyone would be better off with more of it. So, why would natural selection produce people like me who are very low in conscientiousness? Have I only escaped a Darwin award by the grace of the almighty simulator?

I have a hypothesis that low-conscientiousness people may function a bit like dichromats (color blind people) on teams of hunter-gathers. While dichromats can't see some colors, they can detect color-camouflaged objects better than non-color blind people (trichromats). So, teams with mixtures of dichromats and trichromats may have out-competed teams with only trichromats (or only dichromats, for that matter).

Perhaps some diversity of conscientiousness in groups could produce a competitive advantage? There is some evidence in this direction. Just from skimming Wikipedia:

But, specifically, I'd like to surface patterns I've observed in my own experience that I haven't seen discussed elsewhere. I work with, and am related to, many high-conscientiousness people. I've come to appreciate their strengths relative to mine, but I also have first-hand experience with some failure modes of conscientiousness taken too far. Any virtue taken to an extreme can become a vice, as Dieter said. (No, not that Dieter, Dieter Uchtdorf).

Allow me to present four of my observed failure modes of high-consciousness.

#1 Not all messes are worth the risk of cleaning them up

This is the most frequent failure mode I see amongst high-conscientiousness people I work with. In lieu of a technical example, let me give you a more practical one.

I live in a fairly old neighborhood. Houses are typically made of brick, and I'd estimate the mean age of a house in my neighborhood is about 85 years old. Brick and mortar tend to get crumbly in spots over time. Often to keep structural integrity you need to repoint the mortar and/or replace damaged brick. Though, if you haven’t poked at your exterior brick walls or had sufficient experience with deteriorating brick and mortar, you probably wouldn’t be aware of this.

Last summer, I overhead a conversation between two neighbors that could have entered this failure mode, but likely narrowly avoided it. We'll call my neighbors Charlotte and Miranda.

Conscientious Charlotte has an old brick garage that used to have ivy growing on three sides, though she recently removed it from the south side. Removing the ivy left a lot of unsightly "rootlets" on the brick surface of the south side exterior. Charlotte told Miranda that the rootlets look messy and that she'd like to clean them off.

Miranda says her spouse has a pressure washer that may help. Miranda goes home and asks her spouse, Marla, if Charlotte can barrow the power washer. Marla asks "what for?" and Miranda explains Charlotte's predicament. Marla says, "Sure she can borrow it, just let her know that depending on how weathered the brick and mortar is, she may not have a garage standing when she's done power washing the rootlets off." (Marla was completely right, see item #06 here).

A defender of high-conscientiousness could retort here and say “Charlotte's problem wasn't conscientiousness, it was that she wasn't conscientiousness enough.“ I believe this is confusing conscientiousness with circumspection. Circumspection requires some amount of curiosity, which is associated with trait openness. Maybe also some worrying about what could go wrong, which seems like trait neuroticism.

My experience is more that the compulsion to clean up unfamiliar messes among high-conscientiousness people I work with tends to override any thoughtfulness regarding how to account for the unfamiliarity. Routine clean up is fine because it's routine. But when faced with a messy situation they haven't specifically encountered before it seems like their instinct is to address it through cleaning, organizing, sorting, ordering, adding structure, etc. rather than to to step back and say "how can we be sure we’re safely addressing this, or is it even worth the risk of addressing at all?"

Low-conscientiousness people are likely to ask questions like this because we're naturally more adverse to cleaning up messes and, hence, only do it when it's really necessary or when we're coerced to. We'll wonder "is this worth my time?" Or "is this worth my team’s time?" If you’re lucky enough to have a low-conscientiousness team member that’s also high in openness and neuroticism, that may be even better here.

#2 Honestly estimate ROI before micro-optimization (avoid bikeshedding)

So, let's imagine Charlotte still wants to clean the rootlets off her garage. She now realizes she can't safely use a power washer unless she also wants to risk restoring or replacing her garage.

So she carefully goes out with a brush, a bucket of water and detergent, then she proceeds to clean rootlets one small section at a time.

Look, it's Charlotte’s life and it’s her garage. If she wants to toothbrush rootlets off her garage exterior… it’s a free country (assuming you’re reading this in a free country).

I will argue a different calculus applies if you're doing something analogous in a work environment where you're billing a customer who expects value for their dollars, or someone is paying your salary who expects value from your work, or, importantly, if you're asking someone like me to do this when I could be working on something else.

Even after you’ve established a safe method for cleaning up a mess, is it really worth doing in comparison to all the other things you or someone else could be working on?

Situations like this are sometimes called bikeshedding. The term comes from a hypothetical project to build a nuclear power plant. In the midst of all of the planning necessary to safely build the plant, during a project meeting someone raises their hand and says “we should have a bike shed in case employees want to bike to work, and it should be green because we’re about green energy!” Then another person in the meeting says “No, it should be white to reflect more of the suns heat and maintain a lower temperature!” The meeting then spends an inordinate amount of time discussing what color the bike shed should be. The point being a relatively trivial matter derails the larger, more important discussion.

You may think conscientious people are good at avoiding this, my experience is the opposite. Sometimes small details are meaningful, sometimes they’re bikesheds, or rootlets on the garage. Honestly think about the ROI before micro-optimizing in these ways.

Low-conscientiousness people can, again, help here. We're not going to go around toothbrushing rootlets and we're less likely to care about details unless there's a strong argument in favor of their importance.

#3 Avoid supererogation

Supererogation is doing more of something than required. One way to think about it is to imagine someone who commits a crime and gets sentenced to prison for 19 years, then when their 19 year sentence has expired they beg the prison guards to keep then for another 3 years so they can do even more penitence. If you're a Les Misérables fan, imagine Javert releasing Jean Valjean from prison to parole, only to find that Jean Valjean first protests that he hasn’t served enough time, then later complains that the parole terms are too lenient.

This is obviously a bit different than the Wikipedia definition, which describes more in the terms of doing more than what duty requires. But I maintain that those are apt analogies, if hyperbolic by comparison to more day-to-day examples.

(BEGIN SPOILER ALERT)

The straightforward and obvious example of supererogation from Les Misérables is Javert. In fact, Javert is more than an example of supererogation, he’s an example of terminal supererogation. You will often hear people say “follow the spirit of the law, not the letter of the law.” Javert is such a stan for law and duty, he makes anyone strictly following the letter of the law seem eminently reasonable by comparison. Without summarizing the plot, he tracks Valjean over the course of two decades and observes him not just obeying the law, but saving lives and taking care of others, but still wants to return him to prison. Not to get too dark, but Javert commits suicide after unsuccessfully grappling with his predicament.

This is similar to bikeshedding in that the ROI here, relative to other crimes and criminals, is low. (So low that it’s negative—it’s worse than quixotic. Arresting or executing Valjean at any point where Javert encounters him outside of prison would be a net harm to society.) It’s different than bikeshedding as the ROI is a known quantity but still is pursued for philosophical reasons—duty, law, etc. To say nothing of the loss of opportunity Javert trades to continue to pursue Valjean, not to mention the years of life he lost from ending it early.

(END SPOILER ALERT)

If you’re a Javert, a fraction of a Javert, or have such people on your team, maybe add some trusted low-conscientiousness people to help you chill things out a bit? Just stay away from Sacha Baron Cohen’s Inn.

#4 Beware the Superman complex

The Wikipedia definition of the Superman complex is pretty good.

It's different than someone who has a lot of responsibility thrust upon them, or who creates catastrophes to save things and get recognition.

I suspect we all know people who have played this role for parts of their lives. I won’t say this is limited to high-conscientiousness types, but I do see it frequently among many of the ones I know.

I don’t know if there’s deeper, psychoanalytic, reasons why people do this. But I would hope it’s a bit like removing your hand from a hot stove—once you recognize it, you can stop doing it.

Low-conscientiousness types may not be able to analyze the distal reasons for people doing this, but I’m pretty sure we’ll be better than others at spotting when you’re working to your own detriment and potentially the detriment of others.

The general pattern

Apply the principle of maximum parsimony to all things "conscientiousness." With rules, for example, instead of more rules prefer the most parsimonious set of rules—the fewest rules necessary for the maximal outcome.