Continuing our experiments with the voting system, I've enabled two-axis voting for this thread too.

The two dimensions are:

Thanks for this post!

That being said, my model of Yudkowsky, which I built by spending time interpreting and reverse engineering the post you're responding to, feels like you're not addressing his points (obviously, I might have missed the real Yudkowsky's point)

My interpretation is that he is saying that Evolution (as the generator of most biological anchors) explores the solution space in a fundamentally different path than human research. So what you have is two paths through a space. The burden of proof for biological anchors thus lies in arguing that there are enough connections/correlations between the two paths to use one in order to predict the other.

Here it sounds like you're taking as an assumption that human research follows the same or a faster path towards the same point in search space. But that's actually the assumption that IMO Yudkowsky is criticizing!

In his piece, Yudkowsky is giving arguments that the human research path should lead to more efficient AGIs than evolution, in part due to the ability of humans to have and leverage insights, which the naive optimization process of evolution can't do. He also points to the inefficiency of biology in implementing new (in geological-time) complex solutions. On the other hand, he doesn't seem to see a way of linking the amount of resources needed by evolution to the amount of resources needed by human research, because they are so different.

If the two paths are very different and don't even aim at the same parts of the search space, there's nothing telling you that computing the optimization power of the first path helps in understanding the second one.

I think Yudkowsky would agree that if you could estimate the amount of resources needed to simulate all evolution until humans at the level of details that you know is enough to capture all relevant aspects, that amount of resources would be an upper bound on the time taken by human research because that's a way to get AGI if you have the resources. But the number is so vastly large (and actually unknown due to the "level of details" problem) that it's not really relevant for timelines calculations

(Also, I already had this discussion with Daniel Kokotajlo in this thread, but I really think that Platt's law is one of the least cruxy aspects of the original post. So I don't think discussing it further or pointing attention to it is a good idea)

It displeases me that this is currently the most upvoted response: I believe you are focusing on EY's weakest rather than strongest points.

My interpretation is that he is saying that Evolution (as the generator of most biological anchors) explores the solution space in a fundamentally different path than human research. So what you have is two paths through a space. The burden of proof for biological anchors thus lies in arguing that there are enough connections/correlations between the two paths to use one in order to predict the other.

It's hardly surprising there are 'two paths through a space' - if you reran either (biological or cultural/technological) evolution with slightly different initial conditions you'd get a different path. However technological evolution is aware of biological evolution and thus strongly correlated to and influenced by it. IE deep learning is in part brain reverse engineering (explicitly in the case of DeepMind, but there are many other examples). The burden proof is thus arguably more opposite of what you claim (EY claims).

In his piece, Yudkowsky is giving arguments that the human research path should lead to more efficient AGIs than evolution, in part due to the ability of humans to have and leverage insights, which the naive optimization process of evolution can't do. He also points to the inefficiency of biology in implementing new (in geological-time) complex solutions.

To the extent EY makes specific testable claims about the inefficiency of biology, those claims are in err - or at least easily contestable.

EY' strongest point is that the Bio Anchors framework puts far too much weight on scaling of existing models (ie transformers) to AGI, rather than modeling improvement in asymptotic scaling itself. GPT-3 and similar model scaling is so obviously inferior to what is probably possible today - let alone what is possible in the near future - that it should be given very little consideration/weight, just as it would be unwise to model AGI based on scaling up 2005 DL tech.

Thanks for pushing back on my interpretation.

I feel like you're using "strongest" and "weakest" to design "more concrete" and "more abstract", with maybe the value judgement (implicit in your focus on specific testable claims) that concreteness is better. My interpretation doesn't disagree with your point about Bio Anchors, it simply says that this is a concrete instantiation of a general pattern, and that the whole point of the original post as I understand it is to share this pattern. Hence the title who talks about all biology-inspired timelines, the three examples in the post, and the seven times that Yudkowsky repeats his abstract arguments in differents ways.

It's hardly surprising there are 'two paths through a space' - if you reran either (biological or cultural/technological) evolution with slightly different initial conditions you'd get a different path. However technological evolution is aware of biological evolution and thus strongly correlated to and influenced by it. IE deep learning is in part brain reverse engineering (explicitly in the case of DeepMind, but there are many other examples). The burden proof is thus arguably more opposite of what you claim (EY claims).

Maybe a better way of framing my point here is that the optimization processes are fundamentally different (something about which Yudkowsky has written a lot, see for example this post from 13 years ago), and that the burden of proof is on showing that they have enough similarity to extract a lot of info from the evolutionary optimization to the human research optimization.

I also don't think your point about DeepMind works, because DM is working in a way extremely different from evolution. They are in part reverse engineering the brain, but that's a very different (and very human and insight heavy) paths towards AGI than the one evolution took.

Lastly for this point, I don't think the interpretation that "Yudkowsky says that the burden of proof is on showing that the optimization of evolution and human research are non correlated" survives the contact with a text where Yudkowsky constantly berates his interlocutors for assuming such correlation, and keeps drawing again and again the differences.

To the extent EY makes specific testable claims about the inefficiency of biology, those claims are in err - or at least easily contestable.

Hum, I find myself feeling like this comment: Yudkowsky's main point about biology IMO is that brains are not at all the most efficient computational way of implementing AGI. Another way of phrasing it is that Yudkowsky says (according to me) that you could use significantly less hardware and ops/sec to make an AGI.

To be clear, my disagreement concerns more your implicit prioritization - rather than interpretation - of EY's points.

I also don't think your point about DeepMind works, because DM is working in a way extremely different from evolution. They are in part reverse engineering the brain, but that's a very different (and very human and insight heavy) paths towards AGI than the one evolution took.

If search process Y fully reverse engineers the result of search process X, then Y ends up at the same endpoint as X, regardless of the path Y took. Obviously the path is different but also correlated; and reverse engineering the brain makes brain efficiency considerations (and thus some form of bio anchor) relevant.

Yudkowsky's main point about biology IMO is that brains are not at all the most efficient computational way of implementing AGI. Another way of phrasing it is that Yudkowsky says (according to me) that you could use significantly less hardware and ops/sec to make an AGI.

Sure, but that's also the worst part of his argument, because to support it he makes a very specific testable claim concerning thermodynamic efficiency; a claim that is almost certainly off base.

To the extent EY makes specific testable claims about the inefficiency of biology, those claims are in err - or at least easily contestable.

Hum, I find myself feeling like this comment: Yudkowsky's main point about biology IMO is that brains are not at all the most efficient computational way of implementing AGI. Another way of phrasing it is that Yudkowsky says (according to me) that you could use significantly less hardware and ops/sec to make an AGI.

That's unfortunate that you agree; here's the full comment:

You're missing the point!

Your arguments apply mostly toward arguing that brains are optimized for energy efficiency, but the important quantity in question is computational efficiency! You even admit that neurons are "optimizing hard for energy efficiency at the expense of speed", but don't seem to have noticed that this fact makes almost everything else you said completely irrelevant!

Adele claims that I'm 'missing the point' by focusing on energy efficiency, but the specific EY claim I disagreed with is very specifically about energy efficiency! Which is highly relevant, because he then uses this claim as evidence to suggest general inefficiency.

EY specifically said the following, repeating the claim twice in slightly different form:

The result is that the brain's computation is something like half a million times less efficient than the thermodynamic limit for its temperature - so around two millionths as efficient as ATP synthase. The software for a human brain is not going to be 100% efficient compared to the theoretical maximum, nor 10% efficient, nor 1% efficient, even before taking into account

. . .

That is simply not a kind of thing that I expect Reality to say "Gotcha" to me about, any more than I expect to be told that the human brain, whose neurons and synapses are 500,000 times further away from the thermodynamic efficiency wall than ATP synthase, is the most efficient possible consumer of computation

Adele's comment completely ignores the very specific point I was commenting on, and strawman's my position while steelmanning EY's.

I don't think I am following the argument here. You seem focused on the comparison with evolution, which is only a minor part of Bio Anchors, and used primarily as an upper bound. (You say "the number is so vastly large (and actually unknown due to the 'level of details' problem) that it's not really relevant for timelines calculations," but actually Bio Anchors still estimates that the evolution anchor implies a ~50% chance of transformative AI this century.)

Generally, I don't see "A and B are very different" as a knockdown counterargument to "If A required ___ amount of compute, my guess is that B will require no more." I'm not sure I have more to say on this point that hasn't already been said - I acknowledge that the comparisons being made are not "tight" and that there's a lot of guesswork, and the Bio Anchors argument doesn't go through without some shared premises and intuitions, but I think the needed intuitions are reasonable and an update from Bio-Anchors-ignorant starting positions is warranted.

Thanks for the answer!

Unfortunately, I don't have the time at the moment to answer in detail and have more of a conversation, as I'm fully focused on writing a long sequence about pushing for pluralism in alignment and extracting the core problem out of all the implementation details and additional assumption. I plan on going back to analyzing timeline research in the future, and will probably give better answers then.

That being said, here are quick fire thoughts:

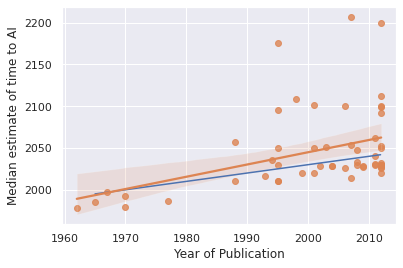

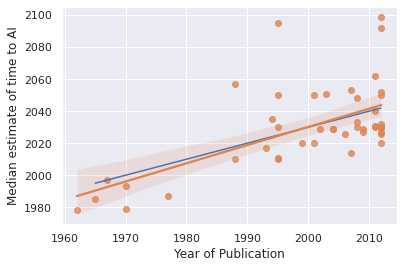

While Matthew says "Overall I find the law to be pretty much empirically validated, at least by the standards I'd expect from a half in jest Law of Prediction," I don't agree: I don't think an actual trendline on the chart would be particularly close to the Platt's Law line. I think it would, instead, predict that Bio Anchors should point to longer timelines than 30 years out.

I ran OLS regression on the data, and this was the result. Platt's law is in blue.

I agree this trendline doesn't look great for Platt's law, and backs up your observation by predicting that Bio Anchors should be more than 30 years out.

However, OLS is notoriously sensitive to outliers. If instead of using some more robust regression algorithm, we instead super arbitrarily eliminated all predictions after 2100, then we get this, which doesn't look absolutely horrible for the law. Note that the median forecast is 25 years out.

It's simply because we each (myself more than her) have an inclination to apply a fair amount of adjustment in a conservative direction, for generic "burden of proof" reasons, rather than go with the timelines that seem most reasonable based on the report in a vacuum.

While one can sympathize with the view that the burden of proof ought to lie with advocates of shorter timelines when it comes to the pure inference problem ("When will AGI occur?"), it's worth observing that in the decision problem ("What should we do about it?") this situation is reversed. The burden of proof in the decision problem probably ought instead to lie with advocates of non-action: when one's timelines are >1 generation, it is a bit too easy to kick the can down the road in various ways — leaving one unprepared if the future turns out to move faster than we expected. Conversely someone whose timelines are relatively short may take actions today that will leave us in a better position in the future, even if that future arrives more slowly than they believed originally.

(I don't think OpenPhil is confusing these two, just that in a conversation like this it is particularly worth emphasizing the difference.)

I agree with this. I often default to acting as though we have ~10-15 years, partly because I think leverage is especially high conditional on timelines in that rough range.

if you think timelines are short for reasons unrelated to biological anchors, I don't think Bio Anchors provides an affirmative argument that you should change your mind.

Eliezer: I wish I could say that it probably beats showing a single estimate, in terms of its impact on the reader. But in fact, writing a huge careful Very Serious Report like that and snowing the reader under with Alternative Calculations is probably going to cause them to give more authority to the whole thing. It's all very well to note the Ways I Could Be Wrong and to confess one's Uncertainty, but you did not actually reach the conclusion, "And that's enough uncertainty and potential error that we should throw out this whole deal and start over," and that's the conclusion you needed to reach.

I would be curious to know what the intended consequences of the forecasting piece were.

A lot of Eliezer's argument seems to me to be pushing at something like 'there is a threshold for how much evidence you need before you start putting down numbers, and you haven't reached it', and I take what I've quoted from your piece to be supporting something like 'there is a threshold for how much evidence you might have, and if you're above it (and believe this forecast to be an overestimate) then you may be free to ignore the numbers here', contra the Humbali position. I'm not particularly confident on that, though.

Where this leaves me is feeling like you two have different beliefs about who will (or should) update on reading this kind of thing, and to what end, which is probably tangled up in beliefs about how good people are at holding uncertainty in their mind. But I'm not really sure what these beliefs are.

The Bio Anchors report is intended as a tool for making debates about AI timelines more concrete, for those who find some bio-anchor-related bound helpful (e.g., some think we should lower bound P(AGI) at some reasonably high number for any year in which we expect to hit a particular kind of "biological anchor"). Ajeya's work lengthened my own timelines, because it helped me understand that some bio-anchor-inspired arguments for shorter timelines didn't have as much going for them as I'd thought; but I think it may have shortened some other folks'.

(The presentation of the report in the Most Important Century series had a different aim. That series is aimed at making the case that we could be in the most important century, to a skeptic.)

I don't personally believe I have a high-enough-quality estimate using another framework that I'd be justified in ignoring bio-anchors-based reasoning, but I don't think it's wild to think someone else might have such an estimate.

What actual important claim can you make on the basis of the estimate? I don't see a way to attach it to timelines, at all. I don't see how to attach it to median or modal compute estimates, at all.

What actual important claim can you make on the basis of the estimate? I don't see a way to attach it to timelines, at all.

Suppose you have no idea when AI will come — for all you know, it could be in one year, or in1000 years — and someone tells you that in year X it will cost $1000 and a few hours to perform as much computation as all of evolution. Are you telling me that that wouldn't update you away from the possibility of AI not coming until 100s of years later?

If you agree that any grad student having enough resources to simulate a rerun of evolution (and humanity collectively having the resources and time to simulate evolution millions of times) would shorten the expected time to AI, then congratulations, you now see a way to attach the 10^43 number to timelines "at all".

I don't see how to attach it to medium or modal compute estimates, at all.

Assuming you mean "median or modal", that's not what that number is meant to be. It's not about median or modal estimates. It's more like a rough upper bound. Did you miss the section of this post titled Bounding vs pinpointing?

someone tells you that in year X it will cost $1000 and a few hours to perform as much computation as all of evolution

Nobody has told you this, though? It is completely coherent to think, and I do in fact expect, this is a much harder task than AGI, even in 1000-year scenarios where NNs get nowhere.

It's a bit like that math trope of proving statements by first assuming their complex generalizations. This doesn't actually get you any information that the assumption didn't trivially hold. When is that theoretical timeline situated, where we have ~infinite compute? How is it relevant to determining actual estimates we actually care about?

E: I'm worried I'm not saying what I'm trying to say well, and that it's just coming across as dismissive, but I really am trying to point at something I think is important and missing in your argument, that would be a lot more apparent if you were explicitly trying to point at the thing you think is useful about what you are doing with this number.

Ah, I may have misunderstood your objection — is it that 10^43 operations is way more than we're going to be able to perform anytime soon (pre-singularity)?

If so, it seems like you may have a point there. According to Wikipedia,

1.12×1036 [flop/s is the] Estimated computational power of a Matrioshka brain, assuming 1.87×1026 Watt power produced by solar panels and 6 GFLOPS/Watt efficiency.

There are 3*10^7 seconds in a year, so that translates to roughly 10^43 computations per year.

I can see why you might think an argument that requires as much computational power as a Matrioshka brain might not be super relevant to AGI timelines if you think we're likely to get AGI before Matrioshka brains.

(Though I will still add that I personally think it is a relevant figure. Someone could be unsure of whether we'll get AGI by the time we have Matrioshka brains or not, and knowing that we could rerun evolution at that scale of compute should probably make them update towards AGI coming first.)

I can see why you might think an argument that requires as much computational power as a Matrioshka brain might not be super relevant to AGI timelines if you think we're likely to get AGI before Matrioshka brains.

Thinking this would be an error though!

Compare:

Suppose all the nations of the world agreed to ban any AI experiment that requires more than 10x as much compute as our biggest current AI. Yay! Your timelines become super long!

Then suppose someone publishes a convincing proof + demonstration that 100x as much compute as our biggest current AI is sufficient for human-level AGI.

Your timelines should now be substantially shorter than they were before you learned this, even though you are confident that we'll never get to 100x. Why? Because you should reasonably assume that if 100x is enough, plausibly 10x is enough too or will be after a decade or so of further research. Algorithmic progress is a thing, etc. etc.

The point is: The main source of timelines uncertainty is what the distribution over compute requirements looks like. Learning that e.g. +12 OOMs would probably be enough or that 10^43 ops would probably be enough are both ways of putting a soft upper bound on the distribution, which therefore translates to more probability mass in the low region that we expect to actually cross.

Your factor 10 is pulling a lot of weight there. It is not particularly uncommon to find linear factors of 10 in efficiency lying around in implementations of algorithms, or the algorithms themselves. In that sense, the one 100x algorithm directly relates to finding the 10x algorithm.

It is however practically miraculous to find linear factors of . What you tend to find instead, when speedups of that magnitude are available, is fundamental improvements to the class of algorithm you are doing. These sorts of algorithmic improvements completely detach you from your original anchor. That you can do brute-force evolution in operations is not meaningfully more informative to whether you can do some other non-brute-force algorithm in operations than knowing you can do brute-force evolution in operations.

The important claim being made is just that evolution of intelligence is possible, and it's plausible that its mechanism can be replicated in an algorithmically cheaper way. The way to use this is to think hard about how you expect that attempt to pan out in practice. The post is arguing however that there's value specifically in as a soft upper bound, which I don't see.

The example I gave was more extreme, involving a mere one OOM instead of ten or twenty. But I don't think that matters for the point I was making.

If you don't think 10^43 is a soft upper bound, then you must think that substantial probability mass is beyond 10^43, i.e. you must think that even if we had 10^43 ops to play around with (and billions of dollars, a giant tech company, several years, etc.) we wouldn't be able to build TAI/AI-PONR/etc. without big new ideas, the sort of ideas that come along every decade or three rather than every year or three.

And that seems pretty unreasonable to me; it seems like at least 90% of our probability mass should be below 10^43.

Hypothetically, if the Bio Anchors paper had claimed that strict brute-force evolution would take ops instead of , what about your argument would actually change? It seems to me that none of it would, to any meaningful degree.

I'm not arguing is the wrong bound, I'm arguing that if you don't actually go ahead and use that number to compute something meaningful, it's not doing any work. It's not actually grounding a relevant prediction you should care about.

I brought up the number because I thought it would be much easier to make this point here than it has turned out to be, but this is emblematic of the problem with this article as a whole. The article is defending that actually their math was done correctly. But Eliezer was not disputing that the math was done correctly, he was disputing that it was the correct math to be doing.

Hypothetically, if the Bio Anchors paper had claimed that strict brute-force evolution would take ops instead of , what about your argument would actually change? It seems to me that none of it would, to any meaningful degree.

If there are 20 vs 40 orders of magnitude between "here" and "upper limit," then you end up with ~5% vs ~2.5% on the typical order of magnitude. A factor of 2 in probability seems like a large change, though I'm not sure what you mean by "to any meaningful degree."

It looks like the plausible ML extrapolations span much of the range from here to . If we were in a different world where the upper bound was much larger, it would be more plausible for someone to think that the ML-based estimates are too low.

If you're dividing your probability from algorithms derived from evolutionary brute force uniformly between now and then, then I would consider that a meaningful degree. But that doesn't seem like an argument being made by Bio Anchors or defended here, nor do I believe that's a legitimate thing you can do. Would you apply this argument to other arbitrary algorithms? Like if there's a known method of calculating X with Y times more computation, then in general there's a 50% chance that there's a method derived from that method for calculating X with times more computation?

I think I endorse the general schema. Namely: if I believe that we can achieve X with flops but not flops (holding everything else constant), then I think that gives a prima facie reason to guess a 50% chance that we could achieve it with flops.

(This isn't fully general, like if you told me that we could achieve something with flops but not I'd be more inclined to guess a median of than .)

I'm surprised to see this bullet being bitten. I can easily think of trivial examples against the claim, where we know the minimum complexity of simple things versus their naïve implementations, but I'm not sure what arguments there are for it. It sounds pretty wild to me honestly, I have no intuition algorithmic complexity works anything like that.

If you think the probability derived from the upper limit set by evolutionary brute force should be spread out uniformly over the next 20 orders of magnitude, then I assume you think that if we bought 4 orders of magnitude today, there is a 20% chance that a method derived from evolutionary brute force will give us AGI? Whereas I would put that probability much lower, since brute force evolution is not nearly powerful enough at those scales.

I would say there is a meaningful probability that a method not derived from evolutionary brute force, particularly scaled up neural networks, will give us AGI at that point with only minimal fiddling. However that general class of techniques does not observe the evolutionary brute force upper bound. It is entirely coherent to say that as you push neural network size, their improvements flatten out and never reach AGI. The chance that a parameter model unlocks AGI given a parameter model doesn't is much larger than the chance that a parameter model unlocks AGI given a parameter model doesn't. So it's not clear how you could expect neural networks to observe the upper bound for an unrelated algorithm, and so it's unclear why their probability distribution would be affected by where exactly that upper bound lands.

I'm also unclear whether you consider this a general rule of thumb for probabilities in general, or something specific to algorithms. Would you for instance say that if there was a weak proof that we could travel interstellar with Y times better fuel energy density, then there's a 50% chance that there's a method derived from that method for interstellar travel with just times better energy density?

I'm surprised to see this bullet being bitten. I can easily think of trivial examples against the claim, where we know the minimum complexity of simple things versus their naïve implementations, but I'm not sure what arguments there are for it. It sounds pretty wild to me honestly, I have no intuition algorithmic complexity works anything like that.

I don't know what you mean by an "example against the claim." I certainly agree that there is often other evidence that will improve your bet. Perhaps this is a disagreement about the term "prima facie"?

Learning that there is a very slow algorithm for a problem is often a very important indicator that a problem is solvable, and savings like to seem routine (and often have very strong similarities between the algorithms). And very often the running time of one algorithm is indeed a useful indicator for the running time of a very different approach. It's possible we are thinking about different domains here, I'm mostly thinking of traditional algorithms (like graph problems, approximation algorithms, CSPs, etc.) scaled to input sizes where the computation cost is in this regime. Though it seems like the same is also true for ML (though I have much less data there and moreover all the examples are radically less crisp).

The chance that a parameter model unlocks AGI given a parameter model doesn't is much larger than the chance that a parameter model unlocks AGI given a parameter model doesn't.

This seems wrong but maybe for reasons unrelated to the matter at hand. (In general an unknown number is much more likely to lie between and than between and , just as an unknown number is more likely to lie between 11 and 16 than between 26 and 31.)

I'm also unclear whether you consider this a general rule of thumb for probabilities in general, or something specific to algorithms. Would you for instance say that if there was a weak proof that we could travel interstellar with Y times better fuel energy density, then there's a 50% chance that there's a method derived from that method for interstellar travel with just times better energy density?

I think it's a good rule of thumb for estimating numbers in general. If you know a number is between A and B (and nothing else), where A and B are on the order of , then a log-uniform distribution between A and B is a reasonable prima facie guess.

This holds whether the number is "The best you can do on the task using method X" or "The best you can do on the task using any method we can discover in 100 years" or "The best we could do on this task with a week and some duct tape" or "The mass of a random object in the universe."

If you think the probability derived from the upper limit set by evolutionary brute force should be spread out uniformly over the next 20 orders of magnitude, then I assume you think that if we bought 4 orders of magnitude today, there is a 20% chance that a method derived from evolutionary brute force will give us AGI? Whereas I would put that probability much lower, since brute force evolution is not nearly powerful enough at those scales.

I don't know what "derived from evolutionary brute force" means (I don't think anyone has said those words anywhere in this thread other than you?)

But in terms of P(AGI), I think that "20% for next 4 orders of magnitude" is a fine prima facie estimate if you bring in this single consideration and nothing else. Of course I don't think anyone would ever do that, but frankly I still think "20% for the next 4 orders of magnitude" is still better than most communities' estimates.

Thanks, I think we're getting closer. The surface level breaks down mostly into two objections here.

The minor objection is, do you expect your target audience to contain people unsure whether we'll get AGI prior to Matrioshka brains, conditional on the latter otherwise happening? My expectation is zero people would both be reading and receptive-to the document, and also hold that uncertainty.

The major objection is, is this an important thing to know? Isn't it wiser to leave that question until people start debating what to allocate their Dyson spheres' resources towards? Are those people you are realistically able to causally affect, even if they were to exist eventually?

When I ask for an “important claim you can make”, there's the assumption that resources are put into this because this document should somehow result in things going better somewhere. Eliezer's critique is surely from this perspective, that he wants to do concrete things to help with probable futures.

Those two points weren't really my deep objections, because I think both of us understand that this is a far enough out future that by that point we'll have found something smarter to do, if it were at all possible, but I'm still a bit too unsure about how you intend this far-future scenario to be informative for those earlier events.

Caveating that I did a lot of skimming on both Bio Anchors and Eliezer's response, the part of Bio Anchors that seemed weakest to me was this:

To be maximally precise, we would need to adjust this probability downward by some amount to account for the possibility that other key resources such as datasets and environments are not available by the time the computation is available

I think the existence of proper datasets/environments is a huge issue for current ML approaches, and you have to assign some nontrivial weight to it being a much bigger bottleneck than computational resources. Like, we're lucky that GPT-3 is trained with the LM objective (predict the next word) for which there is a lot of naturally-occurring training data (written text). Lucky, because that puts us in a position where there's something obvious to do with additional compute. But if we hit a limit following that approach (and I think it's plausible that the signal is too weak in otherwise-unlabeled text) then we're rather stuck. Thus, to get timelines, we'd also need to estimate what dataset/environments are necessary for training AGI. But I'm not sure we know what these datasets/environments look like. An upper bound is "the complete history of earth since life emerged", or something... not sure we know any better.

I think parts of Eliezer's response intersects with this concern, e.g. the energy use analogy. It is the same sort of question, how well do we know what the missing ingredients are? Do we know that compute doesn't occupy enough of the surface area of possible bottlenecks for a compute-based analysis to be worth much? And I'm specifically suggesting that environments/datasets occupy enough of that surface area to seriously undermine the analysis.

Does Bio Anchors deal with this concern beyond the brief mention above (and I missed it, very possible)? Or are there other arguments out there that suggest compute really is all that's missing?

I occasionally hear people make this point but it really seems wrong to me, so I'd like to hear more! Here are the reasons it seems wrong to me:

1. Data generally seems to be the sort of thing you can get more of by throwing money at. It's not universally true but it's true in most cases, and it only needs to be true for at least one transformative or dangerous task. Moreover, investment in AI is increasing; when a tech company is spending $10,000,000,000 on compute for a single AI training run, they can spend 10% as much money to hire 2,000 trained professionals and pay them $100k/yr salaries for 5 years to build training environments and collect/curate data. Not to mention, you are probably doing multiple big AI training runs and you are probably a big tech company that has already set up a huge workforce and data-gathering pipeline with loads of products and stuff.

2. Bitter lesson etc. etc. Most people who I trust on this topic seem to think compute is the main bottleneck, not data.

3. Humans don't need much data; one way we could get transformative or dangerous AI is if we get "human-level AGI," there are plausible versions of this scenario that involve creating something that needs as little or even less data than humans, and while it's possible that the only realistic way to create such a thing is via some giant evolution-like training process that itself requires lots of data... I wouldn't bet on it.

Q. Can you give an example of what progress in data/environments looks like? What progress has been made in this metric over the past 10 years? It'll help me get a sense of what you count as data/environment and what you count as "algorithms." The Bio Anchors report already tracks progress in algorithms.

Final point: I totally agree we should assign nontrivial weight to data being a huge bottleneck, one that won't be overcome by decades and billions of dollars in spending. But everyone agrees on this already; for example, Ajeya assigns 10% of her credence to "basically no amount of compute would be enough with 2020's ideas, not even 10^70 flops." How could recapitulating evolution a billion times over not be enough??? Well, two reasons: Maybe there's some special sauce architecture that can't be found by brute evolutionary search, and maybe data/training environments is an incredibly strong bottleneck. I think the line between these two is blurry. Anyhow, the point is, on my interpretation of Ajeya her framework already assigns something like 5% credence to data/environments being a strong bottleneck. If you think it should be more than that, no problem! Just go into her spreadsheet and make it 25% or whatever you think it is.

Yes, good questions, but I think there are convincing answers. Here's a shot:

1. Some kinds of data can be created this way, like parallel corpora for translation or video annotated with text. But I think it's selection bias that it seems like most cases are like this. Most of the cases we're familiar with seem like this because this is what's easy to do! But transformative tasks are hard, and creating data that really contains latent in it the general structures necessary for task performance, that is also hard. I'm not saying research can't solve it, but that if you want to estimate a timeline, you can't consign this part of the puzzle to a footnote of the form "lots of research resources will solve it". Or, if you do, you might as well relax the whole project and bring only that level of precision across the board.

2. At least in NLP (the AI subfield with which I'm most familiar), my sense of the field's zeitgeist is quite contrary to "compute is the issue". I think there's a large, maybe majority current of thought that our current benchmarks are crap, that performance on them doesn't relate to any interesting real-world task, that optimizing on them is of really unclear value, and that the field as a whole is unfortunately rudderless right now. I think this current holds true among many young DL researchers, not just the Gary Marcuses of the world. That's not a formal survey or anything, just my sense from reading NLP papers and twitter. But similarly, I think the notion that compute is the bottleneck is overrepresented in the LessWrong sphere, vs. what others think.

3. Humans not needing much data is misleading IMO because the human brain comes highly optimized out of the box at birth, and indeed that's the result of a big evolutionary process. To be clear, I agree achieving human-level AI is enough to count as transformative and may well be a second-long epoch on the way to much more powerful AI. But anyway, you have basically the same question to answer there. Namely, I'd still object that Bio Anchors doesn't address the datasets/environments issue regarding making even just human-level AI. Changing the scope to "merely" human doesn't answer the objection.

Q/A. As for recent progress: no, I think there has been very little! I'm only really familiar with NLP, so there might be more in the RL environments. (My very vague sense of RL is that it's still just "video games you can put an agent is" and basically always has been, but don't take it from me.) As for NLP, there is basically nothing new in the last 10 years. We have lots of unlabeled text for language models, we have parallel corpora for translation, and we have labeled datasets for things like question-answering (see here for a larger list of supervised tasks). I think it's really unclear whether any of these have latent in them the structures necessary for general language understanding. GPT is the biggest glimmer of hope recently, but part of the problem even there is we can't even really quantify how close it is to general language understanding. We don't have a good way of measuring this! Without it, we certainly can't train, as we can't compute a loss function. I think there are maybe some arguments that, in the limit, unlabeled text with the LM objective is enough: but that limit might really be more text than can fit on earth, and we'd need to get a handle on that for any estimates.

Final point: I'm more looking for a qualitative acknowledgement that this problem of datasets/environments is hard and unsolved (or arguments for why it isn't), is as important as compute, and, building on that, serious attention paid to an analysis of what it would take to make the right datasets/environments. Rather than consign it to an "everything else" parameter, analyze what it might take to make better datasets/environments, including trying to get a handle on whether we even know how. I think this would make for a much better analysis, and would address some of Eliezer's concerns because it would cover more of the specific, mechanistic story about the path to creating transformative AI.

(Full disclosure: I've personally done work on making better NLP benchmarks, which I guess has given me an appreciation for how hard and unsolved this problem feels. So, discount appropriately.)

Thanks, nice answers!

I agree it would be good to extend the bio anchors framework to include more explicit modelling of data requirements and the like instead of just having it be implicit in the existing variables. I'm generally a fan of making more detailed, realistic models and this seems reasonably high on the priority list of extensions to make. I'd also want to extend the model to include multiple different kinds of transformative task and dangerous task, and perhaps to include interaction effects between them (e.g. once we get R&D acceleration then everything else may come soon...) and perhaps to make willingness-to-spend not increase monotonically but rather follow a boom and bust cycle with a big boom probably preceding the final takeoff.

I still don't think the problem of datasets/environments is hard and unsolved, but I would like to learn more.

What's so bad about text prediction / entropy (GPT-3's main metric) as a metric for NLP? I've heard good things about it, e.g. this.

Re: Humans not needing much data: They are still proof of concept that you don't need much data (and/or not much special, hard-to-acquire data, just ordinary life experience, access to books and conversations with people, etc.) to be really generally intelligent. Maybe we'll figure out how to make AIs like this too. MAYBE the only way to do this is to recapitulate a costly evolutionary process that itself is really tricky to do and requires lots of data that's hard to get... but I highly doubt it. For example, we might study how the brain works and copy evolution's homework, so to speak. Or it may turn out that most of the complexity and optimization of the brain just isn't necessary. To your "Humans not needing much data is misleading IMO because the human brain comes highly optimized out of the box at birth, and indeed that's the result of a big evolutionary process" I reply with this post.

I still don't think we have good reason to think ALL transformative tasks or dangerous tasks will require data that's hard to get. You say this stuff is hard, but all we know is that it's too hard for the amount of effort that's been expended so far. For all we know it's not actually that much harder than that.

If there hasn't been much progress in the last ten years on the data problem, then... do you also expect there to be not much progress in the next ten years either? And do you thus have, like, 50-year timelines?

Re: humans/brains, I think what humans are a proof of concept of is that, if you start with an infant brain, and expose it to an ordinary life experience (a la training / fine-tuning), then you can get general intelligence. But I think this just doesn't bear on the topic of Bio Anchors, because Bio Anchors doesn't presume we have a brain, it presumes we have transformers. And transformers don't know what to do with a lifetime of experience, at least nowhere near as well as an infant brain does. I agree we might learn more about AI from examining humans! But that's leaving the Bio Anchors framing of "we just need compute" and getting into the framing of algorithmic improvements etc. I don't disagree broadly that some approaches to AI might not have as big a (pre-)training phase the way current models do, if, for instance, they figure out a way to "start with" infant brains. But I don't see the connection to the Bio Anchors framing.

What's so bad about perplexity? I'm not saying perplexity is bad per se, just that it's unclear how much data you need, with perplexity as your objective, to achieve general-purpose language facility. It's unclear both because the connection between perplexity and extrinsic linguistic tasks is unclear, and because we don't have great ways of measuring extrinsic linguistic tasks. For instance, the essay you cite itself cites two very small experiments showing correlation between perplexity and extrinsic tasks. One of them is a regression on 8 data points, the other has 24 data points. So I just wouldn't put too much stake in extrapolations there. Furthermore, and this isn't against perplexity, but I'd be skeptical of the other variable i.e. the linguistic task perplexity is regressed against: in both cases, a vague human judgement of whether model output is "human-like". I think there's not much reason to think that is correlated to some general-purpose language facility. Attempts like this to (roughly speaking) operationalize the Turing test have generally been disappointing; getting humans to say "sure, that sounds human" seems to leave a lot to be desired; I think most researchers find them to be disappointingly game-able, vague a critique though that may be. The google Meena paper acknowledges this, and reading between the lines I get the sense they don't think too much of their extrinsic, human-evaluation metric either. E.g., the best they say is, "[inter-annotator] agreement is reasonable considering the questions are subjective and the final results are always aggregated labels".

This is sort of my point in a nutshell: we have put very little effort into telling whether the datasets we have contain adequate signal to learn the functions we want to learn, in part because we aren't even sure how to evaluate those functions. It's not surprising that perplexity correlates with extrinsic tasks to a degree. For instance, it's pretty clear that, to get state-of-the-art low perplexity on existing corpora, transformers can learn the latent rules of grammar, and, naturally doing so correlates with better human judgements of model output. So, grammar is latent in the corpora. But is physics latent in the corpora? It would improve a model's perplexity at least a bit to learn physics: some of these corpora contain physics textbooks with answers to exercises way at the back of the books, so to predict the answers at the back you would have to be able to learn how to do the exercises. But it's unclear whether current corpora contain enough signal to do that. Would we even know how to tell if the model was or wasn't learning physics? I'm personally skeptical that it's happening at all, but I admit that's just based in my subjective assessment of GPT-3 output... again, part of the problem of not having a good way to judge performance outside of perplexity.

As for why all transformative tasks might have hard-to-get-data... well this is certainly speculative, but people sometimes talk about AI-complete tasks, analogizing to the concept of completeness for complexity classes in complexity theory (e.g., NP-complete). I think that's the relevant idea here. The goal being general intelligence, I think it's plausible that most (all? I don't know) transformative tasks are reducible to each other. And I think you also get a hint of this in NLP tasks, where they are weirdly reducible to each other, given the amazing flexibility of language. Like, for a dumb example, the task of question answering entails the task of translation, because you can ask, "How do you say [passage] in French?" So I think the sheer number of tasks, as initially categorized by humans, can be misleading. Tasks aren't as independent as they may appear. Anyway, that's far from a tight argument, but hopefully it provides some intuition.

Honestly I haven't thought about how to incorporate the dataset bottleneck into a timeline. But, I suppose, I could wind up with even longer timelines if I think that we haven't made progress because we don't have the faintest idea how and the lack of progress isn't for lack of trying. Missing fundamental ideas, etc. How do you forecast when a line of zero slope eventually turns up? If I really think we have shown ourselves to be stumped (not sure), I guess I'd have to fall back on general-purpose tools for forecasting big breakthroughs, and that's the sort of vague modeling that Bio Anchors seems to be trying to avoid.

BioAnchors is poorly named, the part you are critiquing should be called GPT-3_Anchors.

A better actual BioAnchor would be based on trying to model/predict how key params like data efficiency and energy efficiency are improving over time, and when they will match/surpass the brain.

GPT-3 could also obviously be improved for example by multi-modal training, active learning, curriculum learning, etc. It's not like it even represents the best of what's possible for a serious AGI attempt today.

Fwiw, I think nostalgebraist's recent post hit on some of the same things I was trying to get at, especially around not having adequate testing to know how smart the systems are getting -- see the section on what he calls (non-)ecological evaluation.

With apologies for the belated response: I think greghb makes a lot of good points here, and I agree with him on most of the specific disagreements with Daniel. In particular:

Overall, I think that datasets/environments are plausible as a major blocker to transformative AI, and I think Bio Anchors would be a lot stronger if it had more to say about this.

I am sympathetic to Bio Anchors's bottom-line quantitative estimates despite this, though (and to be clear, I held all of these positions at the time Bio Anchors was drafted). It's not easy for me to explain all of where I'm coming from, but a few intuitions:

Hopefully that gives a sense of where I'm coming from. Overall, I think this is one of the most compelling objections to Bio Anchors; I find it stronger than the points Eliezer focuses on above (unless you are pretty determined to steel-man any argument along the lines of "Brains and AIs are different" into a specific argument about the most important difference.)

I also find it odd that Bio Anchors does not talk much about data requirements, and I‘m glad you pointed that out.

Thus, to get timelines, we'd also need to estimate what dataset/environments are necessary for training AGI. But I'm not sure we know what these datasets/environments look like.

I suspect this could be easier to answer than we think. After all, if you consider a typical human, they only have a certain number of skills, and they only have a certain number of experiences. The skills and experiences may be numerous, but they are finite. If we can enumerate and analyze all of them, we may be able to get a lot of insight into what is “necessary for training AGI”.

If I were to try to come up with an estimate, here is one way I might approach it:

A couple more thoughts on “what dataset/environments are necessary for training AGI”:

Curated. A few weeks ago I curated the post this is a response to. I'm excited to see a response that argues the criticized report was misinterpreted/misrepresented. I'd be even more excited to see a response to the response–by the authors involved so far or anyone else. Someone once said (approx) that successful conversation must permit four levels: saying X, critiquing X, critiquing the critique, and critiquing the critique of the critique. We're at 3 out of 4.

It was Yudkowsky himself. Perhaps it should be posted to LW, that's not the first time I've seen someone mention it without knowing where to find it.

It's true that Open Philanthropy's public communication tends toward a cautious, serious tone (and I think there are good reasons for this); but beyond that, I don't think we do much to convey the sort of attitude implied above. [...] We never did any sort of push to have it treated as a fancy report.

The ability to write in a facetious tone is wonderful addition to one's writing toolset, equivalent to the ability to use fewer significant digits. This is a separate feature from the feature of "fun to read" and "irreverent". People routinely mistake formalese for some kind of completeness/rigor, and the ability to counter that incorrect inference in them is very useful.

This routine mistake is common knowledge (at least after this comment ;). So "We never did any sort of push to have it treated as fancy" becomes about as defensible as "We never pushed for the last digits in the point estimate '45,321 hair on my head' to be treated as exact", which... is admittedly kinda unfair. Mainly because it's a much harder execution than replacing some digits with zeros.

Eliezer is facetiously pointing out the non-facetiousness in your report (and therefore doing some of the facetiousness-work for you), and here you solemnly point out the hedged-by-default status of it, which... is admittedly kinda fair. But I'm glad this whole exchange (enabled by facetiousness) happened, because it did cause the hedged-by-default-ness to be emphasized.

(I know you said you have good reasons for a serious tone. I do believe there are good reasons for it, such as having to get through to people who wouldn't take it seriously otherwise, or some other silly Keynesian beauty contest. But my guess is that those constraints would apply less on what you post to this forum, which is evidence that this is more about labor and skill than a carefully-arrived-at choice.)

With these two points in mind, it seems off to me to confidently expect a new paradigm to be dominant by 2040 (even conditional on AGI being developed), as the second quote above implies. As for the first quote, I think the implication there is less clear, but I read it as expecting AGI to involve software well over 100x as efficient as the human brain, and I wouldn’t bet on that either (in real life, if AGI is developed in the coming decades—not based on what’s possible in principle.)

I think this misses the point a bit. The thing to be afraid of is not an all-new approach to replace neural networks, but rather new neural network architectures and training methods that are much more efficient than today's. It's not unreasonable to expect those, and not unreasonable to expect that they'll be much more efficient than humans, given how easy it is to beat humans at arithmetic for example, and given fast recent progress to superhuman performance in many other domains.

Unless I’m mistaken, the Bio Anchors framework explicitly assumes that we will continue to get algorithmic improvements, and even tries to estimate and extrapolate the trend in algorithmic efficiency. It could of course be that progress in reality will turn out a lot faster than the median trendline in the model, but I think that’s reflected by the explicit uncertainty over the parameters in the model.

In other words, Holden’s point about this framework being a testbed for thinking about timelines remains unscathed if there is merely more ordinary algorithmic progress than expected.

Power usage was just now coming within a few orders of magnitude of the human brain

Let's put numbers on this. How many bits of evidence does power usage/compute just now coming within a few orders of magnitude of the human brain exert on the prior of how much power/compute a TAI will use?

I'm just going to try to lay out my thoughts on this. Forgive me if it's a bit of an aimless ramble.

If you want to calculate out how much computation power we need for TAI, we need to know two things. A method for creating TAI, and how much computation power such a method needs to create TAI. It seems like biological timelines are attempts to dodge this, and I don't see how or why this would work. Maybe I'm mistaken here, but the report seems to just go "If we get ML methods to function at human brain levels, that will result in TAI" flatly. But, why is it that ML methods should create TAI if you give them the same computation power as the human brain? Where did that knowledge come from? We don't know what the human brain is doing to create intelligence, how do we know that ML can perform as well at similar levels of computation power? We have this open question, "Can modern ML methods result in TAI, and if so, how much computation power does it need to do so?", but the answer "Less than or equal to how much the human brain uses" doesn't obviously connect to anything. Where does it come from, why is it the case? Why can't modern ML only work to create TAI if you give it a million times more computation power than the human brain? What thing is true that makes that impossible? I don't see it, maybe I'm missing something.

Edit: This is really bothering me, so this is an addendum to try and communicate where exactly my confusion lies. Any help would be appreciated.

I understand why we're tempted to use the human brain as a comparison. It's a concrete example of general intelligence. So, assuming our methods can be more efficient at using the computation available to the brain than whatever evolution cooked up, that much computation is enough for at least general intelligence, which is in the worst case enough to be transformative on its own, but almost certainly beaten by something easier.

So, the key question is about our efficiency versus evolution's. And I don't understand how anything could be said regarding this. What if, we go back to the point where programming was invented, and gave them computers capable of beating the computation of the human brain? It'd take them some amount of time to do it, obviously just the computing power isn't enough. What if you gave them a basic course on machine learning? If you plug in the most basic ML techniques into such a computer, I don't naively expect something rivaling general intelligence. So some amount of development is needed. So, we're left with the question, "How much do we need to advance the field of Machine Learning before it can result in transformative AI?". The problem is, that's what we're trying to answer in the first place! If you need to figure out how much research time is needed to develop AI in order to work out how long it'll take to develop AI, I don't see how that's useful information.

I don't now how to phrase this next bit in a way that doesn't come across as insulting, please understand I'm genuinely trying to understand this and would appreciate more detail.

As far I can tell, the paper's way of dealing with the question of the difference of efficiency, is thus; there is a race from the dawn of the neuron until the development of the human being, versus the dawn of computation until the point where we have human brain levels of computation available to us, and the author thinks those should be about the same based on their gut instinct, maybe an order of magnitude off.

This question, is the question. The amount by which we have a more efficient or less efficient design for an intelligent agent is, literally, the most important factor in determining how much computation power is needed to run it. If we have a design that needs ten times more computation power to function similarly, we need ten times more computation power. It's one to one the answer to the question. And it's answered on a gut feeling. I don't get this at all, I'm sorry. I feel I must be wrong on this somewhere, but I don't see where. I really would appreciate it if someone could explain it to me.

The "biological anchors" method for forecasting transformative AI is the biggest non-trust-based input into my thinking about likely timelines for transformative AI. While I'm sympathetic to parts of Eliezer Yudkowsky's recent post on it, I overall disagree with the post, and think it's easy to get a misimpression of the "biological anchors" report (which I'll abbreviate as "Bio Anchors") - and Open Philanthropy's take on it - by reading it.

This post has three sections:

A few notes before I continue:

Bounding vs. pinpointing

Here are a number of quotes from Eliezer in which I think he gives the impression that Biological Anchors assumes transformative AI will be arrived at via modern machine learning methods:

However, the argument given in Bio Anchors does not hinge on an assumption that modern deep learning is what will be used, nor does it set aside the possibility of paradigm changes.

From the section What if TAI is developed through a different path?:

That is, Ajeya (the author) sees the "median" estimate as structurally likely to be overly conservative (a soft upper bound) for reasons including those Eliezer gives, but is also adjusting in the opposite direction to account for factors including the generic burden of proof. (More discussion of "soft bounds" provided by Bio Anchors in this section and this section of the report.)

I made similar arguments in a recent piece, “Biological anchors” is about bounding, not pinpointing, AI timelines. This is my best explanation for skeptics of why I find the framework valuable.

As far as I can tell, the only part of Eliezer's piece that addresses an argument along the lines of the "soft bounding" idea is:

I don't literally think that the "exact GPT architecture" would work to produce transformative AI, but I think something not too far off would be a strong contender - such that having enough compute to afford this extremely brute-force method, combined with decades more time to produce new innovations and environments, does provide something of a "soft upper bound" on transformative AI timelines.

Another way of putting this is that a slightly modified version of what Eliezer calls "tentative [and] probably false]" seems to me to be "tentative and probably true." There's room for disagreement about this, but this is not where most of Eliezer's piece focused.

While I can't be confident, I also suspect that the person in the 2006 or thereabouts part of Eliezer's piece may have intended to argue for something more like a "(soft) upper bound" than a median estimate.

Finally, I want to point out this quote from Bio Anchors, which reinforces that it is intended as a tool for informing AI timelines rather than as a comprehensive generator of all-things-considered AI timelines:

It seems that Eliezer places higher probability on an "entirely different path" sooner than Bio Anchors, but he does not seem to argue for this (and see below for why I don't think it would be a great bet). Instead, he largely argues that the possibility is ignored by Bio Anchors, which is not the case.

Platt's Law and past forecasts

Eliezer writes:

I have a couple issues here.

First, I think Eliezer exaggerates the precision of Platt's Law and its match to the Bio Anchors projection:

I think a softer "It's suspicious that Bio Anchors is in the same 'reasonable-sounding' general range ('a few decades') that AI forecasts have been in for a long time" comment would've been more reasonable than what Eliezer wrote, so from here I'll address that. First, I want to comment on Moravec specifically.

Eliezer characterizes Open Philanthropy as though we think that Hans Moravec's projection was foreseeably silly and overaggressive (see quote above), but now think we have the right approach. This isn't the case.

To expand on what I mean by a reasonable standard and reasonable alternatives:

Returning to the softened version of Platt's Law: according to my current views on timelines (and more so according to Eliezer's), "a few decades" has been a good range for a prediction to be in for the last few decades (again, keeping in mind what context and alternatives I am using). I think this considerably softens the force of an objection like: "You're forecasting a few decades, as many others have over the last few decades; this in itself undermines your case."

None of the above points constitute arguments for the correctness of Bio Anchors. My point is that "Your prediction is like these other predictions" (the thrust of much of Eliezer's piece) doesn't seem to undermine the argument, partly because the other predictions look broadly good according to both my and Eliezer's current views.

A few other reactions to specific parts

On one hand, I think it's a distinct possibility that we're going to see dramatically new approaches to AI development by the time transformative AI is developed.

On the other, I think quotes like this overstate the likelihood in the short-to-medium term.

If the world were such that:

...Then I would be interested in a Bio Anchors-style analysis of projected power usage. As noted above, I would be interested in this as a tool for analysis rather than as "the way to get my probability distribution." That's also how I'm interested in Bio Anchors (and how it presents itself).

I also think we have some a priori reason to believe that human scientists can "use computations" somewhere near as efficiently as the brain does (software), more than we have reason to believe that human scientists can "use power" somewhere nearly as efficiently as the brain does (hardware).

(As a side note, there is some analysis of how nature vs. humans use power in this section of Bio Anchors.)

It's hard for me to understand how it is not a relevant fact: I think we have good reason to believe that humans can use computations at least as intelligently as evolution did.

I think it's perfectly reasonable to push back on 10^43 as a median estimate, but not as a number that has some sort of relevance.

I thought this was a pretty misleading presentation of how Open Philanthropy has communicated about this work. It's true that Open Philanthropy's public communication tends toward a cautious, serious tone (and I think there are good reasons for this); but beyond that, I don't think we do much to convey the sort of attitude implied above. The report's publication announcement was on LessWrong as a draft report for comment, and the report is still in the form of several Google docs. We never did any sort of push to have it treated as a fancy report.