All of johnswentworth's Comments + Replies

It feels like unstructured play makes people better/stronger in a way that structured play doesn't.

What do I mean? Unstructured play is the sort of stuff I used to do with my best friend in high school:

- unscrewing all the cabinet doors in my parents' house, turning them upside down and/or backwards, then screwing them back on

- jumping in and/or out of a (relatively slowly) moving car

- making a survey and running it on people at the mall

- covering pool noodles with glow-in-the-dark paint, then having pool noodle sword fights with them at night while the paint is s

Eh, depends heavily on who's presenting and who's talking. For instance, I'd almost always rather hear Eliezer's interjection than whatever the presenter is saying.

I mean, I see why a rule of "do not spontaneously interject" is a useful heuristic; it's one of those things where the people who need to shut up and sit down don't realize they're the people who need to shut up and sit down. But still, it's not a rule which carves the space at an ideal joint.

An heuristic which errs in the too-narrow direction rather than the too-broad direction but still plausibly captures maybe 80% of the value: if the interjection is about your personal hobbyhorse or pet peave or theory or the like, then definitely shut up and sit down.

If the interjection is about your personal hobbyhorse or pet peave or theory or the like, then definitely shut up and sit down.

I make the simpler request because often rationalists don't seem to be able to tell when this is (or at least tell when others can tell)

Yeah... I still haven't figured out how to think about that cluster of pieces.

It's certainly a big part of my parents' relationship: my mother's old job put both her and my father through law school, after which he worked while she took care of the kids for a few years, and nowadays they're business partners.

In my own bad relationship, one of the main models which kept me in it for several years was "relationships are a thing you invest in which grow and get better over time". (Think e.g. this old post.) And it was true that the relationship got better ove...

I find the "mutual happy promise of 'I got you'" thing... suspicious.

For starters, I think it's way too male-coded. Like, it's pretty directly evoking a "protector" role. And don't get me wrong, I would strongly prefer a woman who I could see as an equal, someone who would have my back as much as I have hers... but that's not a very standard romantic relationship. If anything, it's a type of relationship one usually finds between two guys, not between a woman and <anyone else her age>. (I do think that's a type of relationship a lot of guys crave, to...

I see it as a promise of intent on an abstract level moreso than a guarantee of any particular capability. Maybe more like, "I've got you, wherever/however I am able." And that may well look like traditional gendered roles of physical protection on one side and emotional support on the other, but doesn't have to.

I have sometimes tried to point at the core thing by phrasing it, not very romantically, as an adoption of and joint optimization of utility functions. That's what I mean, at least, when I make this "I got you" promise. And depending on the situati...

I think your experience does not generalize to others as far as you think it does. For instance, personally, I would not feel uncomfortable whispering in a friend's ear for a minute ASMR-style; it would feel to me like a usual social restriction has been dropped and I've been freed up to do something fun which I'm not normally allowed to do.

Indeed!

This post might (no promises) become the first in a sequence, and a likely theme of one post in that sequence is how this all used to work. Main claim: it is possible to get one's needs for benefits-downstream-of-willingness-to-be-vulnerable met from non-romantic relationships instead, on some axes that is a much better strategy, and I think that's how things mostly worked historically and still work in many places today. The prototypical picture here looks like both romantic partners having their separate tight-knit group of (probably same-sex) fri...

No, I got a set of lasertag guns for Wytham well before Battleschool. We used them for the original SardineQuest.

More like: kings have power via their ability to outsource to other people, wizards have power in their own right.

A base model is not well or badly aligned in the first place. It's not agentic; "aligned" is not an adjective which applies to it at all. It does not have a goal of doing what its human creators want it to, it does not "make a choice" about which point to move towards when it is being tuned. Insofar as it has a goal, its goal is to predict next token, or some batch of goal-heuristics which worked well to predict next token in training. If you tune it on some thumbs-up/thumbs-down data from humans, it will not "try to correct the errors in the data supplied...

John's Simple Guide To Fun House Parties

The simple heuristic: typical 5-year-old human males are just straightforwardly correct about what is, and is not, fun at a party. (Sex and adjacent things are obviously a major exception to this. I don't know of any other major exceptions, though there are minor exceptions.) When in doubt, find a five-year-old boy to consult for advice.

Some example things which are usually fun at house parties:

- Dancing

- Swordfighting and/or wrestling

- Lasertag, hide and seek, capture the flag

- Squirt guns

- Pranks

- Group singing, but not at a h

One of my son's most vivid memories of the last few years (and which he talks about pretty often) is playing laser tag at Wytham Abbey, a cultural practice I believe instituted by John and which was awesome, so there is a literal five-year-old (well seven-year-old at the time) who endorses this message!

It took me years of going to bars and clubs and thinking the same thoughts:

- Wow this music is loud

- I can barely hear myself talk, let alone anyone else

- We should all learn sign language so we don't have to shout at the top of our lungs all the time

before I finally realized - the whole draw of places like this is specifically that you don't talk.

That... um... man, you seem to be missing what may be the actual most basic/foundational concept in the entirety of AI alignment.

To oversimplify for a moment, suppose that right now the AI somehow has the utility function u over world-state X, and E[u(X)] is maximized by a world full of paperclips. Now, this AI is superhuman, it knows perfectly well what the humans building it intend for it to do, it knows perfectly well that paperclips only maximize its utility function because of a weird accident of architecture plus a few mislabeled points during traini...

You are a gentleman and a scholar, well done.

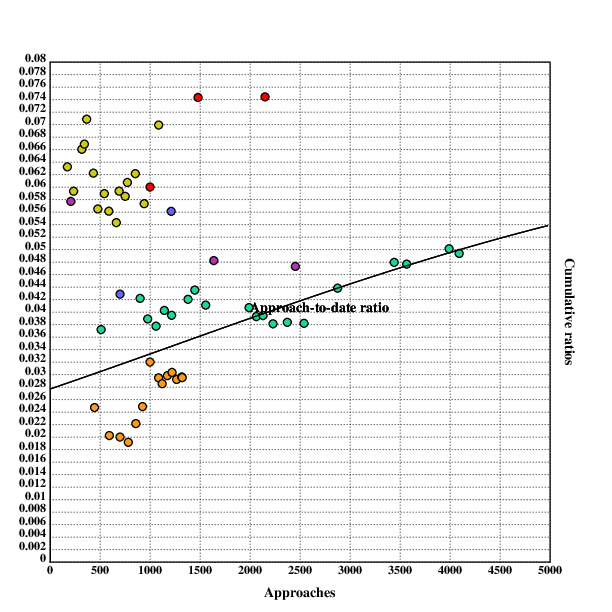

And if numbers from pickup artists who actually practice this stuff look like 5%-ish, then I'm gonna go ahead and say that "men should approach women more", without qualification, is probably just bad advice in most cases.

EDIT-TO-ADD: A couple clarifications on what that graph shows, for those who didn't click through. First, the numbers shown are for getting a date, not for getting laid (those numbers are in the linked post and are around 1-2%), so this is a relevant baseline even for guys who are not primarily aiming for casual sex. Second, these "approaches" involve ~15 minutes each of chatting, so we're not talking about a zero-effort thing here.

There was a lot of "men, you should approach women more" in this one, so I'm gonna rant about it a bit.

I propose a useful rule: if you advise single men to approach women more, you must give a numerical estimate of the rate at which women will accept such an advance. 80%? 20%? 5%? 1%? Put a FUCKING number on it. You can give the number as a function of (other stuff) if you want, or make it conditional on (other stuff), but give some kind of actual number.

You know why? Because I have approached women for dating only a handful of times in my life, and my suc...

Oh look, it's the thing I've plausibly done the best research on out of all humans on the planet (if there's something better out there pls link). To summarize:

Using data from six different pickup artists, more here. My experience with ~30 dates from ~1k approaches is that it's hard work that can get results, but if someone has another route they should stick with that.

(The whole post needs to be revamped with a newer analysis written in Squiggle, and is only partially finished, but that specific section is still good.)

I think it depends a lot on who you’re approaching, in what setting, after how much prior rapport-building.

I’ve gotten together with many women, all of whom I considered very attractive, on the first day I met them, for periods of time ranging from days to months to years. I consider myself to have been a 6 in terms of looks at that time, having been below median income for my city for my entire adult life.

The most important factor, I think, were that I spent a lot of time in settings where the same groups of single people congregate repeatedly for spiritu...

I don't understand why this has to be such a dichotomy?

Good question. I intentionally didn't get into the details in the post, but happy to walk through it in the comments.

Imagine some not-intended-to-be-realistic simplified toy organism with two cell types, A and B. This simplified toy organism has 1001 methyl modification sites which control the cell's type; each site pushes the cell toward either type A or type B (depending on whether the methyl is present or not), and whatever state the majority push toward, that's the type the cell will express.

Under ...

So you're saying that the persistent epigenetic modification is a change in the "equilibrium state" of a potentially methylated location?

Yes.

Does this mean that the binding affinity of the location is the property that changes?

Not quite, it would most likely be a change in concentrations of enzymes or cofactors or whatever which methylate/demethylate the specific site (or some set of specific sites), rather than a change in the site itself.

My default assumption on all empirical ML papers is that the authors Are Not Measuring What They Think They Are Measuring.

It is evidence for the natural abstraction hypothesis in the technical sense that P[NAH|paper] is greater than P[NAH], but in practice that's just not a very good way to think about "X is evidence for Y", at least when updating on published results. The right way to think about this is "it's probably irrelevant".

Good question. The three directed graphical representations directly expand to different but equivalent expressions, and sometimes we want to think in terms of one of those expressions over another.

The most common place this comes up for us: sometimes we want to think about a latent in terms of its defining conditional distribution . When doing that, we try to write diagrams with downstream, like e.g. . Other times, we want to think of in terms of the distribution . When thinking that wa...

Yup, and you can do that with all the diagrams in this particular post. In general, the error for any of the diagrams , , or is for any random variables .

Notably, this includes as a special case the "approximately deterministic function" diagram ; the error on that one is which is .

Good questions. I apparently took too long to answer them, as it sounds like you've mostly found the answers yourself (well done!).

"Approximately deterministic functions" and their diagrammatic expression were indeed in Deterministic Natual Latents; I don't think we've talked about them much elsewhere. So you're not missing any other important source there.

On why we care, a recent central example which you might not have seen is our Illiad paper. The abstract reads:

...Suppose two Bayesian agents each learn a generative model of the same environment. We will a

Does a very strong or dextrous person have more X-power than a weaker/clumsier person, all else equal?

I think that's a straightforward yes, for purposes of the thing the post was trying to point to. Strength/dexterity, like most wizard powers, are fairly narrow and special-purpose; I'm personally most interested in more flexible/general wizard powers. But for me, I don't think it's a-priori about turning knowledge into stuff-happening-in-the-world; it just turns out that knowledge is usually instrumental.

I think the thing I'm trying to point to is importantly wizard power and not artificer power; it just happens to be an empirical fact about today's world that artifice is the most-developed branch of wizardry.

For example:

- Doctors (insofar as they're competent) have lots of wizard power which is importantly not artificer power. Same with lawyers. And pilots. And special ops soldiers. And athletes (though their wizard powers tend to be even more narrow in scope).

- Beyond lawyers, the post mentions a few other forms of social/bureaucratic wizardry, which are importantly wizard power and not artificer power.

Likelihood: maybe 5-30% off the top of my head, obviously depends a lot on operationalization.

Time: however long transformer-based LLMs (trained on prediction + a little RLHF, and minor variations thereon) remain the primary paradigm.

Trying to think of reasons this post might end up being quite wrong, I think the one that feels most likely to me is that these management and agency skills end up being yet another thing that LLMs can do very well very soon. [...]

I'll take the opposite failure mode: in an absolute sense (as opposed to relative-to-other-humans), all humans have always been thoroughly incompetent at management; it's impressive that any organization with dedicated managers manages to remain functional at all given how bad they are (again, in an absolute sense). LLMs are even...

(Note that F, in David's notation here, is a stochastic function in general.)

Yup, that's exactly the right idea, and indeed constructing by just taking a tuple of all the redund 's (or a sufficient statistic for that tuple) is a natural starting point which works straightforwardly in the exact case. In the approximate case, the construction needs to be modified - for instance, regarding the third condition, that tuple of 's (or a sufficient statistic for it) will have much more entropy conditional on than any individual .

Perhaps a more useful prompt for you: suppose something indeed convinces the bulk of the population that AI existential risk is real in a way that's as convincing as the use of nuclear weapons at the end of World War II. Presumably the government steps in with measures sufficient to constitute a pivotal act. What are those measures? What happens, physically, when some rogue actor tries to build an AGI? What happens, physically, when some rogue actor tries to build an AGI 20 or 40 years in the future when alorithmic efficiency and Moore's law have lowered t...

To be clear, I think we at Redwood (and people at spiritually similar places like the AI Futures Project) do think about this kind of question (though I'd quibble about the importance of some of the specific questions you mention here).

Glad you liked it!

I'm very skeptical that focusing on wizard power is universally the right strategy. For example, I think that it would be clearly bad for my effect on existential safety for me to redirect a bunch of my time towards learning about the things you described (making vaccines, using CAD software, etc)...

Fair as stated, but I do think you'd have more (positive) effect on existential safety if you focused more narrowly on wizard-power-esque approaches to the safety problem. In particular, outsourcing the bulk of alignment work (or a pivotal act...

I think that if you wanted to contribute maximally to a cure for aging (and let's ignore the possibility that AI changes the situation), it would probably make sense for you to have a lot of general knowledge. But that's substantially because you're personally good at and very motivated by being generally knowledgeable, and you'd end up in a weird niche where little of your contribution comes from actually pushing any of the technical frontiers. Most of the credit for solving aging will probably go to people who either narrowly specialized in a particular ...

Interesting though about using it to improve one's performance rather than just as an antidepressant or aid to quit smoking.

IIUC the model here is that "Rat Depression" in fact is just depression (see downthread), so the idea is to use bupropion as just an antidepressant. The hypothesis is that basically-physiologically-ordinary depression displays differently in someone who e.g. already has the skills to notice when their emotions don't reflect reality, already has the reality-tracking meta-habits which generate CBT-like moves naturally, has relatively we...

I think this is importantly wrong.

Taking software engineering as an example: there are lots of hobbyists out there who have done tons of small programming projects for years, and write absolutely trash code and aren't getting any better, because they're not trying to learn to produce professional-quality code (or good UI, or performant code). Someone who's done one summer internship with an actual software dev team will produce much higher quality software. Someone who's worked a little on a quality open-source project will also produce much higher quality...

I do think one needs to be strategic in choosing which wizard powers to acquire! Unlike king power, wizard powers aren't automatically very fungible/flexible, so it's all the more important to pick carefully.

I do think there are more-general/flexible forms of wizard power, and it makes a lot of sense to specialize in those. For instance, CAD skills and knowing how to design for various production technologies (like e.g. CNC vs injection molding vs 3D printing) seems more flexibly-valuable than knowing how to operate an injection molding device oneself.

Wow I'm surprised I've never heard of that class, sounds awesome! Thank you.

FYI (cc @Gram_Stone) the 2023 course website has (poor quality edit:nevermind I was accessing them wrong) video lectures.

Edit 2: For future (or present) folks, I've also downloaded local mp4s of the slideshow versions of the videos here, and can share privately with those who dm, in case you want them too or the site goes down.

One can certainly do dramatically better than the baseline here. But the realistic implementation probably still involves narrowing your wizardly expertise to a few domains, and spending most of your time tinkering with projects in them only. And, well, the state of the world being what it is, there's unfortunately a correct answer to the question regarding what those domains should be.

That's an issue I thought about directly, and I think there are some major loopholes. For example: mass production often incentivizes specializing real hard in producing one...

Sure. And the ultimate example of this form of wizard power is specializing in the domain of increasing your personal wizard power, i. e., having deep intimate knowledge of how to independently and efficiently acquire competence in arbitrary domains (including pre-paradigmic, not-yet-codified domains).

Which, ironically, has a lot of overlap with the domain-cluster of cognitive science/learning theory/agent foundations/etc. (If you actually deeply understand those, you can transform abstract insights into heuristics for better research/learning, and vice versa, for a (fairly minor) feedback loop.)

Yeah, hackerspaces are an obvious place to look for wizard power, but something about them feels off. Like, they're trying to be amateur spaces rather than practicing full professional-grade work.

And no, I do not want underlings, whether wizard underlings or otherwise! That's exactly what the point isn't.

You aren’t looking for professional. That takes systems and time, and frankly, king power. Hackers/Makers are about doing despite not going that route, with a philosophy of learning from failure. Now you may be interested in subjects that are more rare in the community, but your interests will inspire others.

I’m a software engineer by trade. I kind of think of myself as an artificer: taking a boring bit of silicone and enchanting it with special abilities. I always tell people the best way to become a wizard like me is to make shitty software. Make s...

Meta: I probably won't respond further in this thread, as it has obviously gone demon. But I do think it's worth someone articulating the principle I'd use in cases like this one.

My attitude here is something like "one has to be able to work with moral monsters". Cremieux sometimes says unacceptable things, and that's just not very relevant to whether I'd e.g. attend an event at which he features. This flavor of boycotting seems like it would generally be harmful to one's epistemics to adopt as a policy.

(To be clear, if someone says "I don't want to be at ...

@Alfred Harwood @David Johnston

If anyone else would like to be tagged in comments like this one on this post, please eyeball-react on this comment. Alfred and David, if you would like to not be tagged in the future, please say so.

Here's a trick which might be helpful for anybody tackling the problem.

First, note that is always a sufficient statistic of for , i.e.

Now, we typically expect that the lower-order bits of are less relevant/useful/interesting. So, we might hope that we can do some precision cutoff on , and end up with an approximate suficient statistic, while potentially reducing the entropy (or some other information content measure) of a bunch. We'd broadcast the cutoff function ...

I wouldn't necessarily expect this to be what's going on, but just to check... are approximately-all the geoguessr images people try drawn from a single dataset on which the models might plausibly have been trained? Like, say, all the streetview images from google maps?

Apparently no. Scott wrote he used one image from Google maps, and 4 personal images that are not available online.

People tried with personal photos too.

I tried with personal photos (screenshotted from Google photos) and it worked pretty well too :

- Identified neighborhood in Lisbon where a picture was taken

- Identified another picture as taken in Paris

Another one identified as taken in a big polish city, the correct answer was among 4 candidates it listed

I didn’t use a long prompt like the one Scott copies in his post, just short „You’re in GeoGuesser, where was this picture taken” or something like that

That I roughly agree with. As in the comment at top of this chain: "there will be market pressure to make AI good at conceptual work, because that's a necessary component of normal science". Likewise, insofar as e.g. heavy RL doesn't make the AI effective at conceptual work, I expect it to also not make the AI all that effective at normal science.

That does still leave a big question mark regarding what methods will eventually make AIs good at such work. Insofar as very different methods are required, we should also expect other surprises along the way, and expect the AIs involved to look generally different from e.g. LLMs, which means that many other parts of our mental pictures are also likely to fail to generalize.

We did end up doing a version of this test. A problem came up in the course of our work which we wanted an LLM to solve (specifically, refactoring some numerical code to be more memory efficient). We brought in Ray, and Ray eventually concluded that the LLM was indeed bad at this, and it indeed seemed like our day-to-day problems were apparently of a harder-for-LLMs sort than he typically ran into in his day-to-day.

You might hope for elicitation efficiency, as in, you heavily RL the model to produce useful considerations and hope that your optimization is good enough that it covers everything well enough.

"Hope" is indeed a good general-purpose term for plans which rely on an unverifiable assumption in order to work.

(Also I'd note that as of today, heavy RL tends to in fact produce pretty bad results, in exactly the ways one would expect in theory, and in particular in ways which one would expect to get worse rather than better as capabilities increase. RL is not something we can apply in more than small amounts before the system starts to game the reward signal.)

That was an excellent summary of how things seem to normally work in the sciences, and explains it better than I would have. Kudos.

Perhaps a better summary of my discomfort here: suppose you train some AI to output verifiable conceptual insights. How can I verify that this AI is not missing lots of things all the time? In other words, how do I verify that the training worked as intended?

Rather, conceptual research as I'm understanding it is defined by the tools available for evaluating the research in question.[1] In particular, as I'm understanding it, cases where neither available empirical tests nor formal methods help much.

Agreed.

But if some AI presented us with this claim, the question is whether we could evaluate it via some kind of empirical test, which it sounds like we plausibly could.

Disagreed.

My guess is that you have, in the back of your mind here, ye olde "generation vs verification" discussion. And in particular, so lon...

I think that OP’s discussion of “number-go-up vs normal science vs conceptual research” is an unnecessary distraction, and he should have cut that part and just talked directly about the spectrum from “easy-to-verify progress” to “hard-to-verify progress”, which is what actually matters in context.

Partly copying from §1.4 here, you can (A) judge ideas via new external evidence, and/or (B) judge ideas via internal discernment of plausibility, elegance, self-consistency, consistency with already-existing knowledge and observations, etc. There’s a big ra...

I think you are importantly missing something about how load-bearing "conceptual" progress is in normal science.

An example I ran into just last week: I wanted to know how long it takes various small molecule neurotransmitters to be reabsorbed after their release. And I found some very different numbers:

- Some sources offhandedly claimed ~1ms. AFAICT, this number comes from measuring the time taken for the neurotransmitter to clear from the synaptic cleft, and then assuming that the neurotransmitter clears mainly via reabsorption (an assumption which I emphas

Another guise of the same problem: it would be great if an LLM could summarize papers for me. Alas, when an LLM is tasked with summarizing a paper, I generally expect it to "summarize" the paper in basically the same way the authors summarize it (e.g. in the abstract), which is very often misleading or entirely wrong. So many papers (arguably a majority) measure something useful, but then the authors misunderstand what they measured and therefore summarize it in an inaccurate way, and the LLM parrots that misunderstanding.

Plausibly the most common reason I...

Here's some problems I ran into the past week which feel LLM-UI-shaped, though I don't have a specific solution in mind. I make no claims about importance or goodness.

Context (in which I intentionally try to lean in the direction of too much detail rather than too little): I was reading a neuroscience textbook, and it painted a general picture in which neurotransmitters get released into the synaptic cleft, do their thing, and then get reabsorbed from the cleft into the neuron which released them. That seemed a bit suspicious to me, because I had previousl...

It looks like some paragraph breaks were lost in this post.

Note that the same mistake, but with convexity in the other direction, also shows up in the OP:

Alice and Bob could toss a coin to decide between options #1 and #2, but then they wouldn’t be acting as an EUM (since EUMs can’t prefer a probabilistic mixture of two options to either option individually).

An EUM can totally prefer a probabilistic mixture of two options to either option individually; this happens whenever utility is convex with respect to resources (e.g. money). For instance, suppose an agent's utility is u(money) = money^2. I offer this agent a...

Did you intend to post this as a reply in a different thread?