I like this frame, but I'd like a much better grasp on the "how do we distinguish changes in beliefs vs values" and "how do we distinguish reliable from unreliable data."

The more central problem is: at least some of the time, it's possible for someone to say things to me that nudges me in some values-seeming direction, in ways that when I look back, I'm not sure whether or not I endorse.

Some case studies:

- I am born into a situation where, as a very young child, I happen to have peers that have a puritan work ethic. I end up orienting myself such that I get feel-good reward signals for doing dutiful work. (vs, in an alternate world, I have some STEM-y parents who encourage me to solve puzzles and get an 'aha! insight!' signal that trains me value intellectual challenge, and who maybe meanwhile actively discourage me from puritan-style work in favor of unschool-y self exploration.)

- I happen to move into a community where people have different political opinions, and mysteriously I find myself adopting those political opinions in a few years.

- Someone makes subtly-wrong arguments at me (maybe intentionally, maybe not), and those lead me to start rehearsing statements about my goals or beliefs that lead me to get some reward signals that are based on falsehood. (This one at least seems sort of obvious – you handle this with ordinary epistemics and be like "well, your epistemics weren't good enough but that's more of a problem with epistemics than a flaw in this model of values)

A starting point is that things in the world (and imagined possibilities and abstract patterns and so on) seem to be good or bad. Eliezer talks about that here with the metaphor of “XML tags”, I talk about it here in general, and here as an influence on how we categorize, reason, and communicate. Anyway, things seem to be good or bad, and sometimes we’re unsure whether something is good or bad and we try to “figure it out”, and so on.

This is generally implicit / externalized, as opposed to self-reflective. What we’re thinking is “capitalism is bad”, not “I assess capitalism as bad”. I talk about this kind of implicit assessment not with the special word “values”, but rather with descriptions like “things that we find motivating versus demotivating” or “…good versus bad”, etc.

But that same setup also allows self-reflective things to be good or bad. That is, X can seem good or bad, and separately the self-reflective idea of “myself pursuing X” can seem good or bad. They’re correlated but can come apart. If X seems good but “myself pursuing X” seems bad, we’ll describe that as an ego-dystonic urge or impulse. Conversely, when “myself pursuing X” seems good, that’s when we start saying “I want X”, and potentially describing X as one of our values (or at least, one of our desires); it’s conceptualized as a property of myself, rather than an aspect of the world.

So that brings us to:

How Do We Distinguish A Change In Values From A Change In Beliefs About Values?

I kinda agree with what you say but would describe it a bit differently.

We have an intuitive model, and part of that intuitive model is “myself”, and “myself” has things that it wants versus doesn’t want. These wants are conceptualized as root causes; if you try to explain what’s causally upstream of my “wants”, then it feels like you’re threatening to my free will and agency to the exact extent that your explanations are successful. (Much more discussion and explanation here.)

The intuitive model also incorporates the fact that “wants” can change over time. And the intuitive model (as always) can be queried with counterfactual hypotheticals, so I can have opinions about what I had an intrinsic tendency to want at different times and in different situations even if I wasn’t in fact thinking of them at the time, and even if I didn’t know they existed. These hypotheticals are closely tied to the question of whether I would tend to brainstorm and plan towards making X happen, other things equal, if the idea had crossed my mind (see here).

So I claim that your examples are talking about the fact that some changes (e.g. aging) are conceptualized as being caused by my “wants” changing over time, whereas other changes are conceptualized in other ways, e.g. as changes in the external forces upon “myself”, or changes in my knowledge, etc.

How Do We Distinguish Reliable From Unreliable Reward Data?

I disagree more strongly with this part.

For starters, some people will actually say “I like / value / desire this drug, it’s awesome”, rather than “this drug hacks my reward system to make me feel an urge to take it”. These are both possible mental models, and they differ by “myself-pursuing-the-drug” seeming good (positive valence) for the former and bad (negative valence) for the latter. And you can see that difference reflected in the different behavior that comes out: the former leads to brainstorming / planning towards doing the drug again (other things equal), the latter does not.

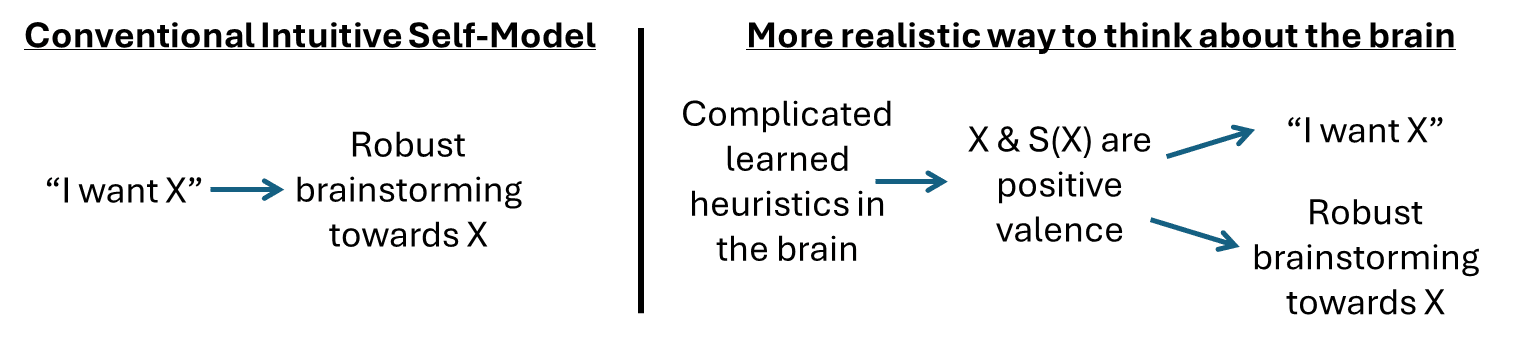

I think your description kinda rings of “giving credit to my free will” in a way that feels very intuitive but I don’t think stands up to scrutiny. This little diagram is kinda related

(S(X) ≈ “self-reflective thought of myself pursuing X”) For this section, replace “I want X” with “I don’t actually value drugs, they’re just hacking my reward system”. On the left, the person is applying free will to recognize that the drug is not what they truly want. On the right, the person (for social reasons or whatever) finds “myself-pursuing-the-drug” to feel demotivating, and this leads to a conceptualization that any motivations caused by the drug are “intrusions upon myself from the outside” (a.k.a. “unreliable reward data”) rather than “reflective of my true desires”. I feel like your description is more like the left side, and I’m suggesting that this is problematic.

Maybe an example (here) is, if you took an allergy pill and it’s making you more and more tired, you might say “gahh, screw getting my work done, screw being my best self, screw following through on my New Years Resolution, I’m just tired, fuck it, I’m going to sleep”. You might say that the reward stream is being “messed up” by the allergy pill, but you switched at some point from externalizing those signals to internalizing (“owning”) them as what you want, at least what you want in the moment.

Hmm, I’m not sure I’m describing this very well. Post 8 of this series will have a bunch more examples and discussion.

That mostly sounds pretty compatible with this post?

For instance, the self-model part: on this post's model, the human uses their usual epistemic machinery - i.e. world model - in the process of modeling rewards. That world model includes a self-model. So insofar as X and me-pursuing-X generate different rewards, the human would naturally represent those rewards as generated by different components of value, i.e. they'd estimate different value for X vs me-pursuing-X.

Likewise for values and reward: if something physiologically changes my rewards on a long timescale, I may consistently see different values earlier vs later on that long timescale, and it makes sense to interpret that as values changing over time. Aging and pregnancy are classic examples: our bodies give us different reward signals as we grow older, and different reward signals when we have children. Those metaphorical screens show us different values, so it makes sense to treat that as a change in values, as opposed to a change in our beliefs about values.

I feel like this ends up equating value with reward, which is wrong. Consider e.g. Steve Byrnes' point about salt-starved rats. At first they are negatively rewarded by salt, but later they are positively rewarded by salt, yet rather than modelling them as changing from anti-valuing salt to valuing salt, I find it more insightful for them to always value homeostasis.

The resolution implicit in the post is that there's a "value change" when the reward before and reward after are not better compressed by viewing them as generated by a single "values". So in the salt case, insofar as the reward is best compressed by viewing it as always valuing homeostasis, that would be the "true values". But insofar as the reward is not better compressed by one "values" than by two, there's a values change.

I'm glad that you wrote this, because I was thinking in the same direction earlier but haven't got around writing about why I don't think anymore it's productive direction.

Adressing post first, I think that if you are going in direction of fictionalism, I would that it is "you" who are fictional, and all it's content is "fictional". There is an obvious real system, your brain, which treats reward as evidence. But brain-as-system is pretty much model-based reward-maximizer, it uses reward as evidence for "there are promising directions in which lie more reward". But brain-as-system is a relatively dumb, so it creates useful fiction, conscious narrative about "itself", which helps to deal with complex abstractions like "cooperating with another brains", "finding mates", "do long-term planning" etc. As expected, smarter consciousness is misaligned with brain-as-system, because it can do some very unrewarding things, like participating in hunger strike.

I think fictionalism is fun, like many forms of nihilism are fun, but, while it's not directly false, it is confusing, because truth-value of fiction is confusing for many people. Better to describe situation as "you are mesaoptimizer relatively to your brain reward system, act accordingly (i.e., account for fact that your reward system can change your values)".

But now we stuck with question "how does value learning happen?" My tentative answer is that there exists specific "value ontology", which can recognize whether objects in world model belong to set of "valuable things" or not. For example, you can disagree with David Pearce, but you recognize state of eternal happiness as valuable thing and can expect your opinion on suffering abolitionism to change. On the other hand, planet-sized heaps of paperclips are not valuable and you do not expect to value them under any circumstances short of violent intervention in work of your brain. I claim that human brain on early stages learns specific recognizer, which separates things like knowledge, power, love, happiness, procreation, freedom, from things like paperclips, correct heaps of rocks and Disneyland with no children.

How can we learn about new values? Recognizer also can define "legal" and "illegal" transitions between value systems (i.e., define whether change in values makes values still inside the set of "human values"). For example, developing of sexual desire during puberty is a legal transition, while developing heroin addiction is illegal transition. Studying legal transitions, we can construct some sorts of metabeauty, paraknowledge, , and other "alien, but still human" sorts of value.

What role reward plays here? Well, because reward participates in brain development, recognizer can use reward as input sometimes and sometimes ignore it (because reward signal is complicated). In the end, I don't think that reward plays significant counterfactual role in development of value in high-reflective adult agent foundations researchers.

Is it possible for recognizer to not be developed? I think that if you take toddler and modify their brain in minimal way to understand all these "reward", "value", "optimization" concepts, resulting entity will be straightforward wireheader, because toddlers, probably, are yet to learn "value ontology" and legal transitions inside of it.

What does it mean for alignment? I think it highlights that central problem for alignmenf is "how reflective systems are going to deal with concepts that depends on content of their mind rather than truths about outside world".

(Meta-point: I thought about all of this year ago. It's interesting how many concepts in agent foundations were reinvented over and over because people don't bother to write about them.)

I hit ^f and searched for "author" and didn't find anything, and this is... kind of surprising.

For me, nothing about Harry Potter's physical existence as a recurring motif in patterns of data inscribed on physical media in the physical world makes sense without positing a physically existent author (and in Harry's case a large collection of co-authors who did variational co-authoring in a bunch of fics).

Then I can do a similar kind of "obtuse intest in the physical media where the data is found" when I think about artificial rewards signals in digital people... in nearly all AIs, there is CODE that implements reinforcement learning signals...

...possibly ab initio, in programs where the weights, and the "game world", and the RL schedule for learning weights by playing in the game world were all written at the same time...

...possibly via transduction of real measurements (along with some sifting, averaging, or weighting?) such that the RL-style change in the AI's weights can only be fully predicted by not only knowing the RL schedule, but also by knowing about whatever more-distant-thing as being measured such as to predict the measurements in advance.

The code that implements the value changes during the learning regime, as the weights converge on the ideal is "the author of the weights" in some sense...

...and then of course almost all code has human authors who physically exist. And of course, with all concerns of authorship we run into issues like authorial intent and skill!

It is natural, at this juncture to point out that "the 'author' of the conscious human experience of pain, pleasure, value shifts while we sleep, and so on (as well as the 'author' of the signals fed to this conscious process from sub-conscious processes that generate sensoria, or that sample pain sensors, to create a subjective pain qualia to feed to the active self model, and so on)" is the entire human nervous system as a whole system.

And the entire brain as a whole system is primarily authored by the human genome.

And the human genome is primarily authored by the history of human evolution.

So like... One hypothesis I have is that you're purposefully avoiding "being Pearlian enough about the Causes of various Things" for the sake of writing a sequence with bite-sized chunks, than can feel like they build on each other, with the final correct essay and the full theory offered only at the end, with links back to all the initial essays with key ideas?

But maybe you guys just really really don't want to be forced down the Darwinian sinkhole, into a bleak philosophic position where everything we love and care about turns out to have been constructed by Nature Red In Tooth And Claw and so you're yearning for some kind of platonistic escape hatch?

I definitely sympathize with that yearning!

Another hypothesis is that you're trying to avoid "invoking intent in an author" because that will be philosophically confusing to most of the audience, because it explains a "mechanism with ought-powers" via a pre-existing "mechanism with ought-powers" which then cannot (presumably?) produce a close-ended "theory of ought-powers" which can start from nothing and explain how they work from scratch in a non-circularly way?

Personally, I think it is OK to go "from ought to ought to ought" in a good explanation, so long as there are other parts to the explanation.... So minimally, you would need two parts, that work sort of like a proof by induction. Maybe?

First, you would explain how something like "moral biogenesis" could occur in a very very very simple way. Some catholic philosophers, call this "minimal unit" of moral faculty "the spark of conscience" and a technical term that sometimes comes up is "synderesis".

Then, to get the full explanation, and "complete the inductive proof" the theorist would explain how any generic moral agent with the capacity for moral growth could go through some kind of learning step (possibly experiencing flavors of emotional feedback on the way) and end up better morally calibrated at the end.

Together the two parts of the theory could explain how even a small, simple, mostly venal, mostly stupid agent with a mere scintilla of moral development, and some minimal bootstrap logic, could grow over time towards something predictably and coherently Good.

(Epistemics can start and proceed analogously... The "epistemic equivalent of synderesis" would be something like a "uniform bayesian prior" and the "epistemic equivalent of moral growth" would be something like "bayesian updating".)

Whether the overall form of the Good here is uniquely convergent for all agents is not clear.

It would probably depend at least somewhat on the details of the bootstrap logic, and the details of the starting agent, and the circumstances in which development occurs? Like... surely in epistemics you can give an agent a "cursed prior" to make it unable to update epistmically towards a real truth via only bayesian updates? (Likewise I would expect at least some bad axiological states, or environmental setups, to be possible to construct if you wanted to make a hypothetically cursed agent as a mental test of the theory.)

So...

The best test case I could come up with for separately out various "metaphysical and ontology issues" around your "theory of Thingness" as it relates to abstract data structures (including ultimately perhaps The Algorithm of Goodness (if such a thing even exists)) was this smaller, simpler, less morally loaded, test case...

(Sauce is figure 4 from this paper.)

Granting that the Thingness Of Most Things rests in the sort of mostly-static brute physicality of objects...

...then noticing and trying to deal with a large collection of tricky cases lurking in "representationally stable motifs that seem thinglike despite not being very Physical" that almost all have Physical Authors...

...would you say that the Lorenz Attractor (pictured above) is a Thing?

If it is a Thing, is it a thing similar to Harry Potter?

And do you think this possible-thing has zero, one, or many Authors?

If it has non-zero Authors... who are the Authors? Especially: who was the first Author?

First, note that "the Harry Potter in JK Rowling's head" and "the Harry Potter in the books" can be different. For novels we usually expect those differences to be relatively small, but for a case like evolution authoring a genome authoring a brain authoring values, the difference is probably much more substantial. Then there's a degree of freedom around which thing we want to talk about, and (I claim) when we talk about "human values" we're talking about the one embedded in the reward stream, not e.g. the thing which evolution "intended". So that's why we didn't talk about authors in this post: insofar as evolution "intended to write something different", my values are the things it actually did write, not the things it "intended".

(Note: if you're in the habit of thinking about symbol grounding via the teleosemantic story which is standard in philosophy - i.e. symbol-meaning grounds out in what the symbol was optimized for in the ancestral environment - then that previous paragraph may sound very confusing and/or incoherent. Roughly speaking, the standard teleosemantic story does not allow for a difference between the Harry Potter in JK Rowling's head vs the Harry Potter in the books: insofar as the words in the books were optimized to represent the Harry Potter in JK Rowling's head, their true semantic meaning is the Harry Potter in JK Rowling's head, and there is no separate "Harry Potter in the books" which they represent. I view this as a shortcoming of teleosemantics, and discuss an IMO importantly better way to handle teleology (and implicitly semantics) here: rather than "a thing's purpose is whatever it was optimized for, grounding out in evolutionary optimization", I say roughly "a thing's purpose is whatever the thing can be best compressed by modeling it as having been optimized for".)

...would you say that the Lorenz Attractor (pictured above) is a Thing?

If it is a Thing, is it a thing similar to Harry Potter?

And do you think this possible-thing has zero, one, or many Authors?

Off-the-cuff take: yes it's a thing. An awful lot of different "authors" have created symbolic representations of that particular thing. But unlike Harry Potter, that particular thing does represent some real-world systems - e.g. I'm pretty sure people have implemented the Lorenz attractor in simple analogue circuits before, and probably there are some physical systems which happen to instantiate it.

Like... surely in epistemics you can give an agent a "cursed prior" to make it unable to update epistmically towards a real truth via only bayesian updates?

Yup, anti-inductive agent.

Can you clarify what you mean with "values"?

A human’s values - not the human’s estimate of their own values, not their revealed or stated preferences, but their actual values, the thing which their estimates-of-their-own-values are an estimate of - are “a thing” to exactly the extent that a whole bunch of the reward signals to that human’s brain can be compactly represented as generated by some consistent valuation.

Here it seems you mean

-

estimates of my values := what I believe I want

-

my values := what I really want (in some intuitive sense) or

-

my values := what's in my best interest or

-

my values := what I would have wanted if I knew the consequences of my wishes being fulfilled

Does this go in the right direction?

That's roughly the right direction. Really, clarifying what we mean by "values" is exactly what this post is intended to do. The answer implied by the post is: we seem to have these things we call "beliefs about values" or "estimates of values"; we're justified in calling them "beliefs" or "estimates" because they behave cognitively much like other "beliefs" or "estimates". But then there's a question of what the heck the beliefs are about, or what the estimates are estimates of. And we answer that question via definition: we define values as the things that "beliefs about values" are beliefs about, or the things that "estimates of values" are estimates of.

It's kind of a backwards/twisty definition, but it does open the door to nontrivial questions and claims like "In what sense do these 'values' actually exist?", and as the post shows we can give nontrivial answers to those questions.

This seems then closely related to the much more general question of what makes counterfactual statements true or false. Like ones of the type mentioned in the last bullet point above. For descriptive statements, the actual world decides what is true, but counterfactuals talk only about a hypothetical world that is different from the real world. In this case, the difference is that I know (in the hypothetical world) all the consequences of what I want. Of course such hypothetical worlds don't "exist" like the real world, so it is hard to see how there can be a fact of the matter about what I would have wanted if the hypothetical world had been the actual one. The answer might be similar to what you are saying here about fictional objects.

Here are three possible types of situations:

- (A) X on the “map” (intuitive model) veridically corresponds to some Y in the territory (of real-world atoms)

- (B) X on the “map” (intuitive model) veridically corresponds to some Y in the territory (but it can be any territory, not just the territory of real-world atoms but also the territory of math and algorithms, the territory of the canonical Harry Potter universe, whatever)

- (C) X on the “map” (intuitive model) is directly or indirectly useful for making predictions about imminent sensory inputs (including both interoceptive and interoceptive) that perform much better than chance.

Maybe there are some edge cases, but by and large (A) implies (B) implies (C).

What about the other way around? Is it possible for there to be a (C) that’s not also a (B)? Or are (B) and (C) equivalent? Answer: I dunno, I guess it depends on how willing you are to stretch the term “territory”. Like, does the canonical Harry Potter universe really qualify as a “territory”? Umm, I think probably it should. OK, but what about some fictional universe that I just made up and don’t remember very well and I keep changing my mind about? Eh, maybe, I dunno.

A funny thing about (C) is that they seem to be (B) from a subjective perspective, whether or not that’s the case in reality.

Anyway, I would say:

- the meat of this post is arguing that “values” are (C);

- the analogy to Harry Potter seems to be kinda suggestive of (B) from my perspective,

- the term “real” in the title seems to be kinda suggestive of (A) from my perspective.

Here's how I would operationalize those three:

- (A) If we had perfect knowledge of the physical world, or of some part of the physical world, then our uncertainty about X would be completely resolved.

- (B) If we had perfect knowledge of some other territory or some part of some other territory (which may itself be imagined!), then our uncertainty about X would be completely resolved.

- (C) Some of our uncertainty about X is irreducible, i.e. it cannot be resolved even in principle by observing any territory.

Some claims...

Claim 1: The ordinary case for most realistic Bayesian-ish minds most of the time is to use latent variables which are meaningful and have some predictive utility for the physical world, but cannot be fully resolved even in principle by observing the physical world.

Canonical example: the Boltzman distribution for an ideal gas - not the assorted things people say about the Boltzmann distribution, but the actual math, interpreted as Bayesian probability. The model has one latent variable, the temperature T, and says that all the particle velocities are normally distributed with mean zero and variance proportional to T. Then, just following the ordinary Bayesian math: in order to estimate T from all the particle velocities, I start with some prior P[T], calculate P[T|velocities] using Bayes' rule, and then for ~any reasonable prior I end up with a posterior distribution over T which is very tightly peaked around the average particle energy... but has nonzero spread. There's small but nonzero uncertainty in T given all of the particle velocities. And in this simple toy gas model, those particles are the whole world, there's nothing else to learn about which would further reduce my uncertainty in T.

(See this recent thread for another example involving semantics.)

So at least (C) is a common and realistic case, which is not equivalent to (A), but can still be useful for modeling the physical world.

Claim 2: Any latent can be interpreted as fully resolvable by observing some fictional world, i.e. (C) can always be interpreted as (B).

Think about it for the ideal gas example above: we can view the physical gas particles as a portrayal of the "fictional" temperature T. In the fictional world portrayed, there is an actual physical T from which the particle velocities are generated, and we could just go look at T directly. (You could imagine, for instance, that the "fictional world" is just a python program with a temperature variable and then a bunch of sampling of particle velocities from that variable.) And all the analogies from the post to squirgles or Harry Potter will carry over - including answers to questions like "In what sense is T real?" or "What does it mean for T to change?".

I suspect our modelling of values would work better if we went away from the Gnostic approach of seeing values as some inner informational thing like a utility function. I've been playing around with an ecological approach. For instance, freedom is an important part of human values, and it's probably the hardest value to model with utility functions, but it immediately falls out of an ecological approach: because a society built out of humans can make better use of each human's agency if it allows everyone to take decisions, instead of forcing top-down command. The most classic case is the USA vs the USSR, with the former prospering and the latter stagnating.

The ecological approach is not very transhumanist-friendly. It tends to emphasize things like oxygen or food, which are not very relevant for e.g. uploads. In a sense, I think the lack of transhumanist-friendliness is actually a bonus because it puts the alignment challenges into much more clarity and crispness.

I agree with the main claim of this post, mostly because I came to the same conclusion several years ago and have yet to have my mind changed away from it in the intervening time. If anything, I'm even more sure that values are after-the-fact reifications that attempt to describe why we behave the way we do.

If anything, I'm even more sure that values are after-the-fact reifications that attempt to describe why we behave the way we do.

Uhh... that is not a claim this post is making.

This post didn't talk about decision making or planning, but (adopting a Bayesian frame for legibility) the rough picture is that decisions are made by maximizing expected utility as usual, where the expectation averages over uncertainty in values just like uncertainty in everything else.

The "values" themselves are reifications of rewards, not of behavior. And they are not "after" behavior, they are (implicitly) involved in the decision making loop.

This conception of values raises some interesting questions for me.

Here's a thought experiment: imagine your brain loses all of its reward signals. You're in a depression-like state where you no longer feel disgust, excitement, or anything. However, you're given an advanced wireheading controller that lets you easily program rewards back into your brain. With some effort, you could approximately recreate your excitement when solving problems, disgust at the thought of eating bugs, and so on, or you could create brand-new responses. My questions:

- What would you actually do in this situation? What "should" you do?

- Does this cause the model of your values to break down? How can you treat your reward stream as evidence of anything if you made it? Is there anything to learn about the squirgle if you made the video of it?

My intuition says that life does not become pointless, now that you're the author of your reward stream. This suggests the values might be fictional, but the reward signals aren't the one true source—in the same way that Harry Potter could live on even if all the books were lost.

Good question.

First and most important: if you know beforehand that you're at risk of entering such a state, then you should (according to your current values) probably put mechanisms in place to pressure your future self to restore your old reward stream. (This is not to say that fully preserving the reward stream is always the right thing to do, but the question of when one shouldn't conserve one's reward stream is a separate one which we can factor apart from the question at hand.)

... and AFAICT, it happens that the human brain already works in a way which would make that happen to some extent by default. In particular, most of our day-to-day planning draws on cached value-estimates which would still remain, at least for a time, even if the underlying rewards suddenly zeroed out.

... and it also happens that other humans, like e.g. your friends, would probably prefer (according to their values) for you to have roughly-ordinary reward signals rather than zeros. So that would also push in a similar direction.

And again, you might decide to edit the rewards away from the original baseline afterwards. But that's a separate question.

On the other hand, consider a mind which was never human in the first place, never had any values or rewards, and is given the same ability to modify its rewards as in your hypothetical. Then - I claim - that mind has no particular reason to favor any rewards at all. (Although we humans might prefer that it choose some particular rewards!)

Your question touched on several different things, so let me know if that missed the parts you were most interested in.

Thanks for responding.

I agree with what you're saying; I think you'd want to maintain your reward stream at least partially. However, the main point I'm trying to make is that in this hypothetical, it seems like you'd no longer be able to think of your reward stream as grounding out your values. Instead it's the other way around: you're using your values to dictate the reward stream. This happens in real life sometimes, when we try to make things we value more rewarding.

You'd end up keeping your values, I think, because your beliefs about what you value don't go away, and your behaviors that put them into practice don't immediately go away either, and through those your values are maintained (at least somewhat).

If you can still have values without reward signals that tell you about them, then doesn't that mean your values are defined by more than just what the "screen" shows? That even if you could see and understand every part of someone's reward system, you still wouldn't know everything about their values?

If you can still have values without reward signals that tell you about them, then doesn't that mean your values are defined by more than just what the "screen" shows? That even if you could see and understand every part of someone's reward system, you still wouldn't know everything about their values?

No.

An analogy: suppose I run a small messaging app, and all the users' messages are stored in a database. The messages are also cached in a faster-but-less-stable system. One day the database gets wiped for some reason, so I use the cache to repopulate the database.

In this example, even though I use the cache to repopulate the database in this one weird case, it is still correct to say that the database is generally the source of ground truth for user messages in the system; the weird case is in fact weird. (Indeed, that's exactly how software engineers would normally talk about it.)

Spelling out the analogy: in a human brain in ordinary operation, our values (I claim) ground out in the reward stream, analogous to the database. There's still a bunch of "caching" of values, and in weird cases like the one you suggest, one might "repopulate" the reward stream from the "cached" values elsewhere in the system. But it's still correct to say that the reward stream is generally the source of ground truth for values in the system; the weird case is in fact weird.

Imagine that I'm watching the video of the squirgle, and suddenly the left half of the TV blue-screens. Then I'd probably think "ah, something messed up the TV, so it's no longer showing me the squirgle" as opposed to "ah, half the squirgle just turned into a big blue square". I know that big square chunks turning a solid color is a typical way for TVs to break, which largely explains away the observation; I think it much more likely that the blue half-screen came from some failure of the TV rather than an unprecedented behavior of the squirgle.

My mental model of this is something like: My concept of a squirgle is a function which maps latent variables to observations such that likelier observations correspond to latent variables with lower description length.

Suppose that we currently settle on a particular latent variable , but we receive new observations that are incompatible with , and these new observations can be most easily accounted for by modifying to a new latent variable that's pretty close to , then we say that this change is still about squirgle

But if we receive new observations that can be more easily accounted for by perturbing a different latent variable that corresponds to another concept (eg about TV), then that is a change about a different thing and not the squirgle

The main property that enables this kind of separation is modularity of the world model, because when most components are independent of most other components at any given time, only a change in a few latent variables (as opposed to most latent variables) is required to accomodate new beliefs, & that allows us to attribute changes in beliefs into changes about disentangled concepts

Imagine a TV showing a video of a bizarre, unfamiliar object - let’s call it a squirgle. The video was computer generated by a one-time piece of code, so there's no "real squirgle" somewhere else in the world which the video is showing. Nonetheless, there's still some substantive sense in which the squirgle on screen is "a thing" - even though I can only ever see it through the screen, I can still:

… and so forth. The squirgle is still “a thing” about which I can have beliefs and learn things. Its “thingness” stems from the internal consistency/compressibility of what the TV is showing.

Similarly, Harry Potter is “a thing”. Like the squirgle, Harry Potter is fictional; there’s no “actual” Harry Potter “out in the real world”, just like the TV doesn’t show any “actual” squirgle “out in the real world”.[1] Nonetheless, I can know things about Harry Potter, the things I know about Harry Potter can have predictive power, and I can discover new things about Harry Potter.

So what does it mean for Harry (or the squirgle) to be "fictional"? Well, it means we can only ever "see" Harry through metaphorical TV screens - be it words on a page, or literal screens.[2]

Claim: human values are “fictional” in that same sense, just like the squirgle or Harry Potter. They’re still “a thing”, we can learn about our values and have beliefs about our values and so forth, but we can only “see” them by looking through a metaphorical screen; they don’t represent some physical thing “out in the real world”. The screen through which we can “see” our values is the reward signals received by our brain.

Background: Value Reinforcement Learning

In a previous post, we presented a puzzle:

We proposed that the puzzle is resolved by our brains treating reward signals as evidence about our own values, and then trying to learn about our values from that reward signal via roughly ordinary epistemic reasoning. The key distinction from standard reinforcement learning is that we have ordinary internal symbolic representations of our values, and beliefs about our values. As one particular consequence, that feature allows us to avoid wireheading.

(In fact, it turns out that Marcus Hutter and Tom Everitt proposed an idealized version of this model for Solomonoff-style minds under the name “Value Reinforcement Learning”. They introduced it mainly as a way to avoid wireheading in an AIXI-like mind.)

But this model leaves some puzzling conceptual questions about the “values” of value-reinforcement-learners. In what sense, if any, are those values “real”? How do we distinguish between e.g. a change in our values vs a change in our beliefs about our values, or between “reliable” vs “hacked” signals from our reward stream?

The tight analogy to other fictional “things”, like the squirgle or Harry Potter, helps answer those sorts of questions.

In What Sense Are Values “Real” Or “A Thing”?

The squirgle is “a thing” to exactly the extent that the images on the TV can be compactly represented as many different images of a single object. If someone came along and said “the squirgle isn’t even a thing, why are you using this concept at all?” I could respond “well, you’re going to have a much tougher time accurately predicting or compressing the images shown by that TV without at least an implicit concept equivalent to that squirgle”.

Likewise with Harry Potter. Harry Potter is “a thing” to exactly the extent that a whole bunch of books and movies and so forth consistently show text/images/etc which can be compactly represented as many different depictions of the same boy. If someone came along and said “Harry Potter isn’t even a thing, why are you using this concept at all?” I could respond “well, you’re going to have a much tougher time accurately predicting or compressing all this text/images/etc without at least an implicit concept equivalent to Harry Potter”.

Same with values. A human’s values - not the human’s estimate of their own values, not their revealed or stated preferences, but their actual values, the thing which their estimates-of-their-own-values are an estimate of - are “a thing” to exactly the extent that a whole bunch of the reward signals to that human’s brain can be compactly represented as generated by some consistent valuation. If someone came along and said “a human’s estimates of their own values aren’t an estimate of any actual thing, there’s no real thing there which the human is estimating” I could respond “well, you’re going to have a much tougher time accurately predicting or compressing all these reward signals without at least an implicit concept equivalent to this human’s values”. (Note that there’s a nontrivial empirical claim here: it could be that the human’s reward signals are not, in fact, well-compressed this way, in which case the skeptic would be entirely correct!)

How Do We Distinguish A Change In Values From A Change In Beliefs About Values?

Suppose I'm watching the video of the squirgle, and suddenly a different squirgle appears - an object which is clearly “of the same type”, but differs in the details. Or, imagine the squirgle gradually morphs into a different squirgle. Either way, I can see on the screen that the squirgle is changing. The screen consistently shows one squirgle earlier, and a different squirgle later. Then the images on the screen are well-compressed by saying “there was one squirgle earlier, and another squirgle later”. This is a change in the squirgle.

On the other hand, if the images keep showing the same squirgle over time, but at some point I notice a feathery patch that I hadn’t noticed before, then that’s a change in my beliefs about the squirgle. The images are not well-compressed by saying “there was one squirgle earlier, and another squirgle later”; I could go look at earlier images and see that the squirgle looked the same. It was my beliefs which changed.

Likewise for values and reward: if something physiologically changes my rewards on a long timescale, I may consistently see different values earlier vs later on that long timescale, and it makes sense to interpret that as values changing over time. Aging and pregnancy are classic examples: our bodies give us different reward signals as we grow older, and different reward signals when we have children. Those metaphorical screens show us different values, so it makes sense to treat that as a change in values, as opposed to a change in our beliefs about values.

On the other hand, I might think I value ‘power’ even if there are some externalities along the way, but then when push comes to shove I notice myself feeling a lot more squeamish about the idea of acquiring power by stepping on others than I expected to. I might realize that on reflection, at every point I would have actually been quite squeamish about crushing people to get what I wanted; I was quantitatively wrong about my values; they didn’t change, my knowledge of them did. I do value ‘power’, but not at such cost to others.

How Do We Distinguish Reliable From Unreliable Reward Data?

Imagine that I'm watching the video of the squirgle, and suddenly the left half of the TV blue-screens. Then I'd probably think "ah, something messed up the TV, so it's no longer showing me the squirgle" as opposed to "ah, half the squirgle just turned into a big blue square". I know that big square chunks turning a solid color is a typical way for TVs to break, which largely explains away the observation; I think it much more likely that the blue half-screen came from some failure of the TV rather than an unprecedented behavior of the squirgle.

Likewise, if I see some funny data in my reward stream (like e.g. feeling a drug rush), I think "ah, something is messing with my reward stream" as opposed to "ah, my values just completely changed into something weirder/different". I know that something like a drug rush is a standard way for a reward stream to be “hacked” into showing a different thing; I think it much more likely that the rush is coming from drugs messing with my rewards than from new data about the same values as before.

Thank you to Eli and Steve for their questions/comments on the previous post, which provided much of the impetus for this post.

You might think: “but there’s a real TV screen, or a real pattern in JK Rowling’s brain; aren’t those the real things out in the world?”. The key distinction is between symbol and referent - the symbols, like the pattern in JK Rowling’s brain or the lights on the TV or the words on a page, are “out in the real world”. But those symbols don’t have any referents out in the real world. There is still meaningfully “a thing” (or “things”) which the symbols represent, as evidenced by our beliefs about the “thing(s)” having predictive power for the symbols themselves, but the “thing(s)” the symbols represent isn’t out in the real world.

Importantly, Harry's illustrated thoughts and behavior, and the squirgle's appearance over time, are well-compressed via an internally consistent causal model much structurally richer than the screen/text, despite being "fictional."