Decomposing Agency — capabilities without desires

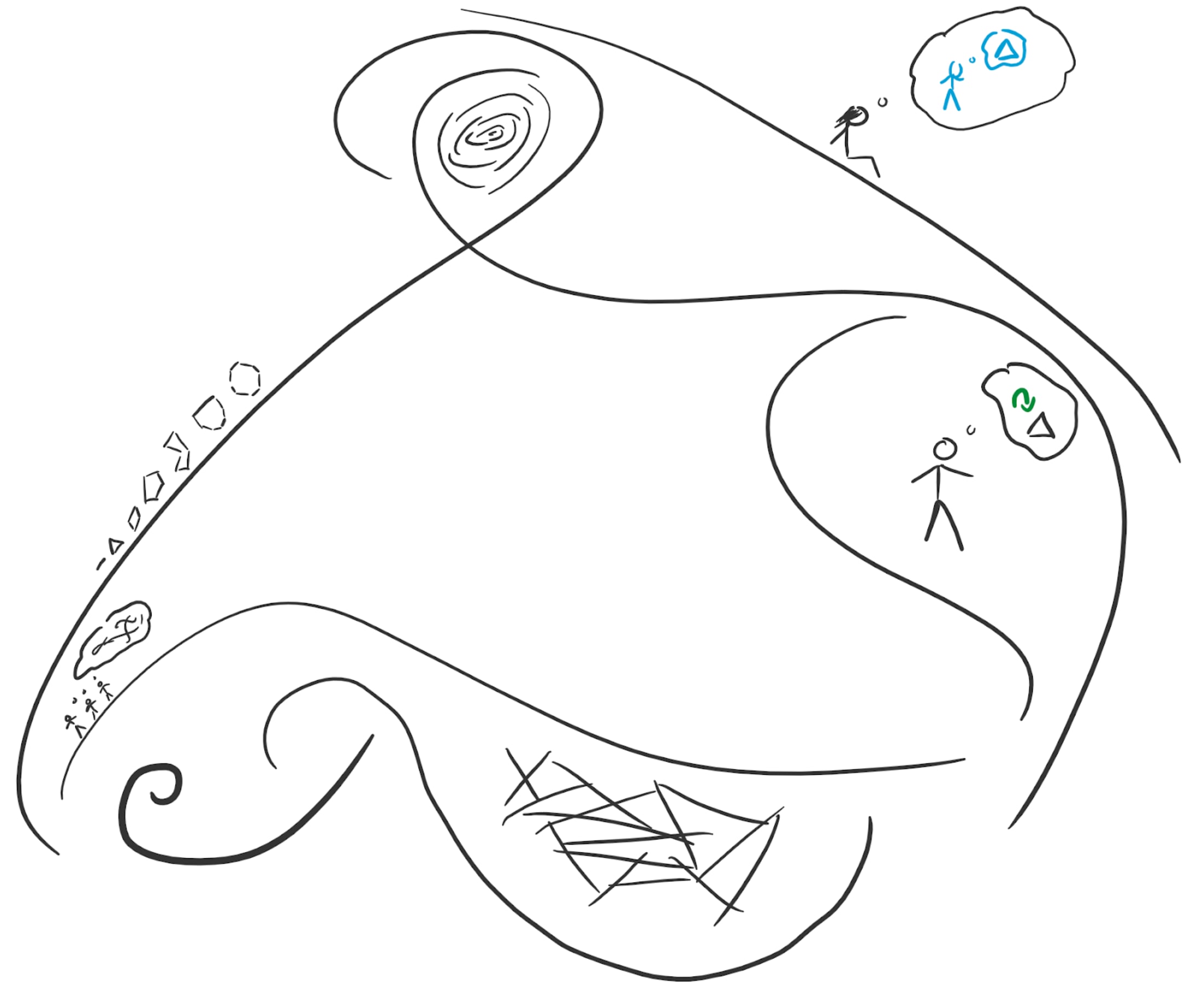

What is an agent? It’s a slippery concept with no commonly accepted formal definition, but informally the concept seems to be useful. One angle on it is Dennett’s Intentional Stance: we think of an entity as being an agent if we can more easily predict it by treating it as having some beliefs and desires which guide its actions. Examples include cats and countries, but the central case is humans. The world is shaped significantly by the choices agents make. What might agents look like in a world with advanced — and even superintelligent — AI? A natural approach for reasoning about this is to draw analogies from our central example. Picture what a really smart human might be like, and then try to figure out how it would be different if it were an AI. But this approach risks baking in subtle assumptions — things that are true of humans, but need not remain true of future agents. One such assumption that is often implicitly made is that “AI agents” is a natural class, and that future AI agents will be unitary — that is, the agents will be practically indivisible entities, like single models. (Humans are unitary in this sense, and while countries are not unitary, their most important components — people — are themselves unitary agents.) This assumption seems unwarranted. While people certainly could build unitary AI agents, and there may be some advantages to doing so, unitary agents are just an important special case among a large space of possibilities for: * Components which contain important aspects of agency (without necessarily themselves being agents); * Ways to construct agents out of separable subcomponents (none, some, or all of which may be reasonably regarded agents in their own right). We’ll begin an exploration of these spaces. We’ll consider four features we generally expect agents to have[1]: * Goals * Things they are trying to achieve * e.g. I would like a cup of tea * Implementation capacity * The ability to act in the world *