After years of clumsily trying to pick up neuroscience by osmosis from papers, I finally got myself a real book — Affective Neuroscience, by Jaak Panksepp, published in 1998, about the neuroscience of emotions in the (animal and human) brain.

What surprised me at first was how controversial it apparently was, at the time, to study this subject at all.

Panksepp was battling a behaviorist establishment that believed animals did not have feelings. Apparently the rationale was that, since animals can’t speak to tell us how they feel, we can only infer or speculate that a rat feels “afraid” when exposed to predator odor, and such speculations are unscientific. (Even though the rat hides, flees, shows stressed body language, experiences elevated heart rate, and has similar patterns of brain activation as a human would in a dangerous situation; and even though all science is, to one degree or another, indirect inference based on observations.)

If anything, Panksepp believed, (and I agree) that the study of emotions in animals is often a better source of knowledge than psychological experiments on humans.

Human psychology experiments tend to be…indirect. For ethical reasons, we do not cut open healthy people’s brains; we do not genetically modify them, drug them, or lesion them to eliminate a neurotransmitter or destroy a brain region. We also generally do not put human experimental subjects in situations that provoke extremes of rage, terror, or lust. We give people questionnaires and little games, and monitor them noninvasively.

This means that we don’t get the kinds of unambiguous, clear-cut information one would ideally like about “this observable physical phenomenon in the brain is a necessary-and-sufficient condition for this emotional state.” We’re limited by people’s ability to self-report inaccurately, by the experimental interventions being imperfect proxies for real-world emotional situations, and by our small repertoire of safe ways to intervene directly on the human brain.

We have more freedom to intervene in animal experiments, and more ability to generate consistent, clear-cut results.

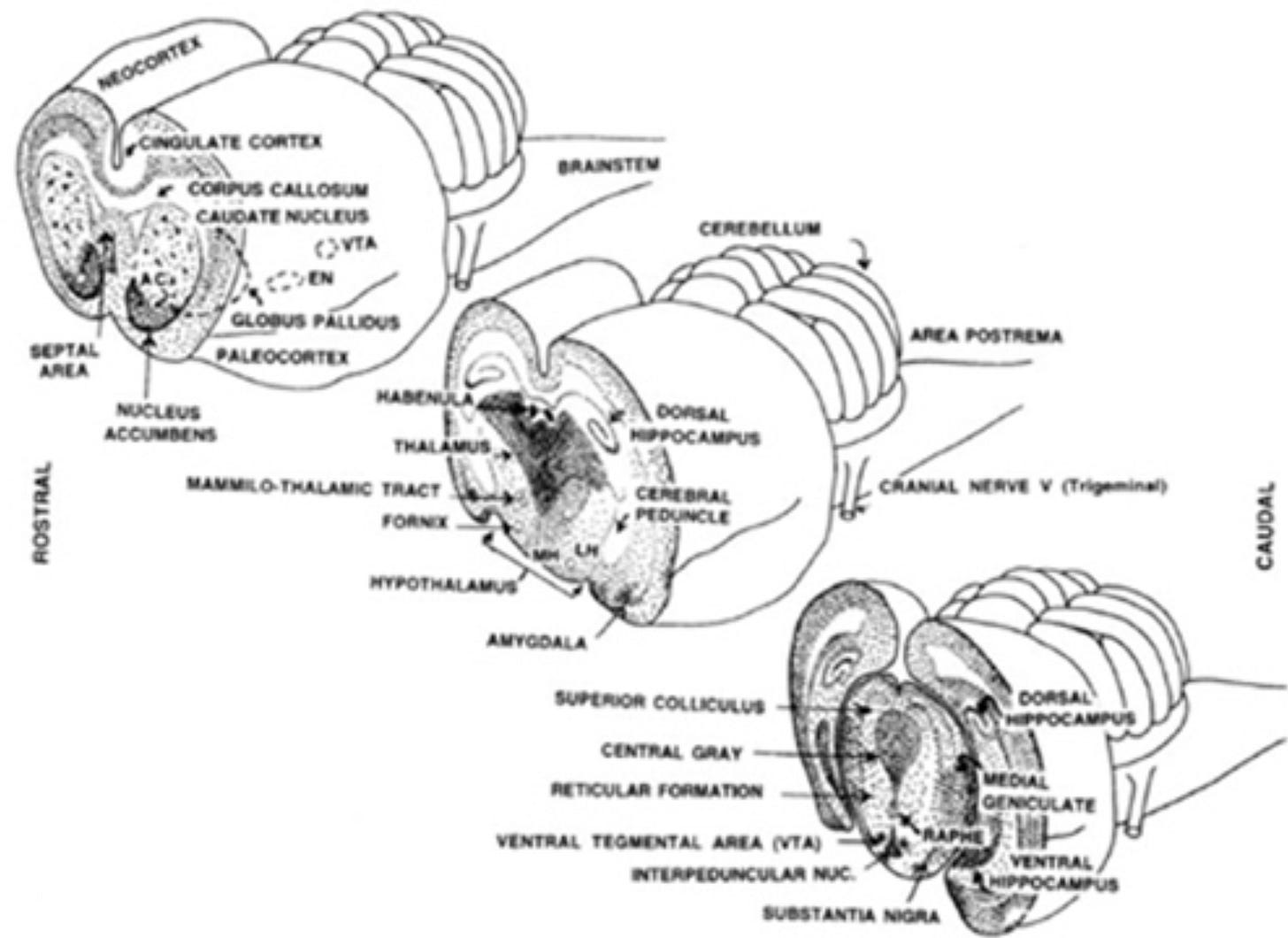

Panksepp’s thesis is that at least some basic emotions are “pan-mammalian” — all mammals (including humans), have “circuits” in the same brain regions (mostly in the subcortical limbic system) which produce emotions in pretty much the same way.

What he calls the RAGE circuit, for instance, can be triggered experimentally in animals or humans through rage-inducing situations or by artificial stimulation in relevant brain regions; it can be blocked by lesions those critical brain regions; if you ask humans what it feels like, they say they’re angry, and while we can’t ask animals about their feelings, they demonstrate aggressive behavior when RAGE is triggered. This all adds up to a pretty plausible evidence base that the same thing is going on in rats, cats, and humans.

Complex social emotions like “shame” or “xenophobia” may indeed be human-specific; we certainly don’t have good ways to elicit them in animals, and (at the time of the book but probably also today) we don’t have well-validated neural correlates of them in humans either.

In fact, we probably shouldn’t even expect that there are special-purpose brain systems for cognitively complex social emotions. Neurotransmitters and macroscopic brain structures evolve over hundreds of millions of years; we should only expect to see “special-purpose hardware” for capacities that humans share with other mammals or vertebrates.1

But ancient, simple emotions are more tractable to understand neurologically. The best studied examples he gives are SEEK, FEAR, RAGE, and PANIC.

SEEK: “Something Wonderful is Around The Corner”

The SEEK circuit prompts animals to explore.

In herbivores (like rats and mice) it is active during foraging for food; in predators (like cats) it is active during hunting.

Both of these behaviors, of course, are “searching for food”, though apparently few people before Panksepp made the connection.2

The SEEK circuit is also active during “cruising” for sex (i.e. when animals look around for a suitable sex partner.)

The common thread here is “appetitive” behaviors — the process of actively seeking out food, sex, or other necessities and pleasures.

These are contrasted with “consummatory” behavior, which is the final step in getting a desired thing. For food, hunting/foraging and then tasting/biting/chewing are appetitive behaviors, while swallowing is a consummatory behavior; for sex, cruising/courting and then copulating are appetitive behaviors, while orgasm is a consummatory behavior. The SEEK system is not active during the consummatory phase, when the animal “gets satisfaction” and usually rests in a satiated state for some time. SEEKing is about desire, eagerness, anticipation, excitement — but not contentment.

The SEEK circuit is primarily driven by the neurotransmitter dopamine, and anatomically by the “ventral dopamine pathway” going from the ventral tegmental area (at the top of the midbrain, where dopamine is first released) up through the ventral striatum (aka basal ganglia) and finally up to the lateral hypothalamus.

The lateral hypothalamus is where the original “wireheading” experiments were done, demonstrating that rats would eagerly self-stimulate their own brains (by pushing a button that connected to an implanted electrode) in preference to food or drink.

If you stimulate humans in that region, they can tell you how it feels — they all report it feels as though “something very exciting is about to happen.”

It’s not exactly pleasure (there are other brain regions where stimulation produces intense physical pleasure or even orgasms) but it is a positive emotion.

Stimulating the lateral hypothalamus in rats does not make them passively blissed out; it makes them more active. They explore and sniff more.

We also have some sense of what SEEK feels like because dopaminergic drugs exist; amphetamines release dopamine, and L-DOPA is a dopamine precursor given to dopamine-deficient Parkinson’s patients. People on dopaminergic drugs are more active, confident, and enthusiastic, though at high doses this sometimes “overshoots” into anxiety or irritability. Conversely, people with dopamine deficiencies (like Parkinson’s) or people on dopamine-blocking drugs (like typical antipsychotics) are slow-moving or motor-impaired, have difficulty initiating actions, and are often depressed.

In classical conditioning experiments, where a rat has to learn a behavior to get a reward, dopamine activity in the lateral hypothalamus is the first change that occurs as the rat notices a “connection” between the conditioned stimulus and the reward — before the rat has behaviorally figured out how to get the reward. As the rat is getting the hang of the right behavior for obtaining the reward, the dopaminergic activity moves to the basal ganglia, which are involved in motor learning and habit formation.

This dopamine-based SEEK circuit thus governs a process for going from “insights” or “aha” connections to learned, goal-oriented behavior. (And it’s also relevant to how dopamine-blocking antipsychotics can shut down the false “insights” typical of psychotic episodes.)

There’s “downward” connections going from the cortex into the core SEEK system, which is how we can learn to desire or be excited about new and cognitively complex things. SEEKing can get pretty abstract in humans (we can get excited or fascinated by particular arrangements of pixels on a screen). And even in animals, the core classical conditioning insight is that they can learn to anticipate rewards from a novel, arbitrary cue that they’ve learned is associated with rewards.

The SEEK system is agnostic to what you seek. Activating it makes us (animals and humans) nonspecifically “more seek-y”, more interested in all sorts of rewards and more prone to subjectively anticipate that good things are close at hand if we just go looking for them.

FEAR: “Watch Out — Or Flee!”

The FEAR system is, of course, a response to danger, especially danger from predators. It prompts animals to freeze when it’s mildly or chronically stimulated — to stop moving, avoid being noticed, and be vigilant for danger — and to flee when it’s intensely, acutely stimulated.

Some languages have different words for the “anxiety” of anticipating an unknown potential danger, versus the “terror” of reacting to an immediate, present danger. German Angst and Schreck, for instance, or Greek phobos and deimos. But neurologically, it’s all governed by the same systems, just differing in intensity and acuteness. The “anxiety” response (hide and watch) is for when you see a tiger nearby; the “terror” response (run as fast as you can) is for when the tiger sees you.

The FEAR system ranges from the periaqueductal gray (PAG) up to the anterior and medial hypothalamus, and up further to the amygdala.

You can provoke intense FEAR responses in animals by artificially stimulating the PAG, anterior-medial hypothalamus, or anterior-medial amygdala. Low-intensity stimulation causes freezing; high-intensity stimulation causes fleeing. We know that stimulating animals in the PAG is causing them subjective distress and not just motor responses because they will strenuously avoid returning to places where they were once PAG-stimulated.

If you stimulate humans in the PAG, they usually express fear with very concrete metaphors — “someone is chasing me”.

It was once thought that fear was only a learned response to pain, but animals have “hard-coded” fears of dangers they’ve never experienced. Rodents innately fear bright, open spaces and predator smells; primates (including humans) are innately afraid of snakes, spiders, darkness, high places, and angry-looking strangers of their own species.

However, of course you can learn to fear new things, and “fear learning” is a standard animal research paradigm where an animal is trained to fear an arbitrary cue associated with an aversive experience. Again, there are cortical projections into the FEAR circuit; humans, with our big cortices, can learn to fear quite abstract and cognitively complex things.

A common thread here is that “higher” cortical thoughts and perceptions feed into the deeper subcortical emotional circuits — we humans are able to “inform” the core emotions with lots of additional context or top-down conceptual thought — but it’s possible to have the emotions with a small cortex (like most non-human mammals) or with no cortex at all (like a “decorticate” animal with the cortex surgically removed.)

Decorticate mammals, by the way, are surprisingly competent! They’re active (even hyperactive), and they respond to stimuli with species-typical behaviors. They’re just more impulsive and somewhat cognitively impaired. Part of what gives us confidence that subcortical, pan-mammalian brain circuits are important is the fact that you can get so much normal animal behavior with the subcortical brain alone.

We study the neurochemistry of fear a lot in the process of trying to develop anti-anxiety medications; unfortunately, the main neurotransmitter in the FEAR circuit is glutamate, the brain’s “all-purpose” excitatory neurotransmitter that’s used almost everywhere in the brain, and it’s hard to inhibit it without a lot of collateral damage.

You can block glutamate NMDA receptors with drugs like ketamine; inject it right in the amygdala and it’ll block fear learning. (But administer it systemically and you’ll get altered mental states that aren’t really compatible with everyday life.) You can also stimulate the inhibitory GABA receptors with alcohol, barbiturates, and benzodiazepines — again, these will block anxiety very well, but they have tradeoffs as everyday “anxiety meds”, as they can be addictive and sedating.

You can also induce fear by injecting ACTH, the pituitary hormone involved in the HPA axis stress response that also releases the “stress hormone” cortisol. And, you can induce panic attacks in humans and fear behaviors in animals with neuropeptides like cholestokinin. But neither of these have really panned out as targets for anti-anxiety meds either. (Ultimately, the “differentiator” of the FEAR circuit is less the neurotransmitters it uses and more the brain regions it engages; as non-invasive stimulation of deep brain structures develops, we may get more specific anti-anxiety tools.)

RAGE: “Get Me Out Of Here! Make It Stop!”

The RAGE response is a violent, aggressive “fighting” reaction to being trapped, constrained, frustrated, or in pain.

RAGE is fundamentally different from other kinds of animal “aggression” like intermale competition (think two rams butting heads) or predatory hunting. Both competing and hunting involve upside — a chance to “win” sex, territory, or a meal — and so, unsurprisingly, animals find them rewarding.

RAGE isn’t like that. It’s purely aversive. It’s sometimes called “defensive aggression” or “affective rage”, and it only happens under threat. Think of a “cornered cat”, back arched, hair standing on end, hissing and clawing.

Animals experiencing RAGE show stressed body language, sympathetic activation (like fast heart rate), and desperate, but not very effectively lethal struggling and “fighting back”.

A natural evolutionary explanation is that, while FEAR is the response to approaching threat (the tiger lurking or chasing you), RAGE is the response to a threat that has already arrived, when it’s too late to hide or flee and you need to fight your way out (the tiger has you in its jaws).

Human infants can be provoked to RAGE simply by holding their arms down to their sides; physical restraint and tactile irritants, in both humans and other mammals, prompt frustrated thrashing and lashing out.

Disappointment also provokes RAGE — “the vending machine ate my quarter”, any kind of frustration of not getting an expected reward. If you train an animal to expect a food reward and then take it away, you can get a RAGE response. In social animals with dominance hierarchies, dominant animals experience RAGE when they don’t get their expected submission displays from subordinates.

SEEK and RAGE are related but mutually inhibitory, in other words; SEEK is active when you anticipate a reward, but it turns to RAGE when you fail to obtain it. A predator might experience RAGE when the prey escapes. Maybe the evolutionary rationale is that a last spasm of “desperate effort” fueled by RAGE might regain the lost reward?

The RAGE regions of the brain are in the PAG, medial hypothalamus, and medial amygdala (close to the PAG, MH, and amygdala regions involved in FEAR, but not quite in the same locations).

Stimulate these regions in a cat and you get what used to be called “sham rage” — all the same hissing, hair-standing-on-end, clawing reactions we see when cats are threatened. It was called “sham” because researchers once assumed that the cat wasn’t really “feeling” rage but only being triggered to engage in a bunch of rage-like motor behaviors. But we currently think the stimulation is a subjectively unpleasant experience for the cat, because the cat will go out of its way to avoid RAGE stimulation or anything associated with it (like places it’s been RAGE-stimulated before.)

Stimulate a monkey in the RAGE regions and it’ll beat up other monkeys, starting with the lowest-status ones in the dominance hierarchy.

As with other “emotion circuits”, there are lots of cortical projections into the RAGE circuit; social animals can use their sophisticated cortex-based cognitive abilities to assess whom they can afford to lose their temper at. But you don’t need a cortex at all to experience RAGE itself.

“Intermale” aggression (competitive, territorial fights between male mammals) seems neurologically distinct from RAGE. It’s driven by vasopressin and testosterone, whose receptors follow a slightly different path than the RAGE circuits — the anterior hypothalamus, with projections to the hippocampus, septum, and PAG. Testosterone injection does not directly trigger the RAGE circuits, and indeed human men given testosterone report feeling good, not bad.

So what neurotransmitters are involved in RAGE?

As with FEAR, the primary neurotransmitter is glutamate, which is used very widely throughout the brain; you can’t block glutamate globally without ruining lots of things.

There are also some special-purpose neuropeptides that trigger the RAGE circuit, like substance P, which is involved in sensing pain. (Unsurprisingly, since pain tends to trigger RAGE.) Could you make an anti-aggression drug by blocking substance P? Maybe in principle, but in practice these appear to be primarily anti-vomiting drugs that don’t do so well in trials for psych issues like depression.

As with FEAR, we have pharmacological ways to induce RAGE, but not really to block it specifically.

PANIC: “I Want My Mama!”

Panksepp uses the name PANIC to refer to the separation-distress circuit, the brain mechanisms involved in mammal infants crying for their mothers. The name PANIC comes from his hypothesis that it’s also the mechanism involved in panic attacks.

A typical nursing infant of any mammal species will make some kind of “distress vocalizations” when separated from its mother, and will be uninterested in eating or exploring; when the mother comes back, the infant will be comforted and show signs of recovering from this distress.

If the infant is abandoned or orphaned, it will eventually give up on making distress vocalizations and will become generally low-energy, eating and exploring little, in a pattern that looks something like “grief” or “depression.” Human infants will “fail to thrive” and literally die if severely emotionally neglected (as in overcrowded orphanages).

We can observe a distribution of brain areas where electrical stimulation makes young animals do more separation-distress cries (this research is mostly done in rats and guinea pigs.) This “PANIC circuit” ranges from the PAG at the top of the midbrain, out to connections in the dorsomedial thalamus, the ventral septal area, and many sites in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. These sites also track the distribution of beta-endorphin receptors.

Indeed, there’s a tight relationship between separation distress and endorphins.

Opiate drugs (which stimulate the internal endorphin receptors) prevent separation distress. Opiates also seem to make animals less social generally: chicks follow their mothers less, rodents spend less time in close proximity with each other, dogs wag their tails less, primates do less social grooming, and humans report less need to socialize.

The reverse is true with opioid receptor antagonists like naloxone: when opioid receptors are blocked, rodents increase social proximity, dogs wag their tails more, and young primates cling more to their mothers and also make more social solicitations to other members of their troops.

The theory is that pleasant social contact, especially maternal care for infants but also grooming and companionship in adult social animals, feels good and releases natural opioids in the brain. Exogenous opiate drugs “substitute for” the pleasant opioid-releasing effects of social comfort, which is why they reduce social motivations; opiate addiction may very literally be a disease of loneliness in which people take a drug that directly replicates the feelings normally produced by social comfort. Opioid blocking, by contrast, intensifies separation distress and social motivation because the craving remains “unsatisfied”.

Oxytocin receptors also pretty much track the locations of the PANIC circuit, and administering oxytocin in the brain can block separation distress calls. Oxytocin is also essential for maternal care behaviors in mammal mothers; it’s the signal for milk to be released during nursing, and it seems to be released both during mother-child cuddling and during sex. Opioids and oxytocin both seem to correspond to the “opposite of separation distress” — the pleasant, comfortable feelings of maternal care (in both mother and child), as well as positive sexual and social contact.

Separation distress is not identical with the FEAR circuit.

For one thing, young animals stop making separation-distress cries in the presence of a FEAR-promoting danger cue (like a predator smell). It wouldn’t do to cry for your mother if it would reveal your location to a predator!

For another thing, opiates do not block fear effectively.

Panic attacks in humans also seem to be distinct from fear, at least pharmacologically. Benzodiazepines are anti-anxiety drugs that calm fear but don’t prevent panic attacks, while tricyclic antidepressants like imipramine prevent panic attacks but don’t do anything about fear.3

Subjectively, a panic attack and separation distress both feel like a “desperate need for immediate aid.”

The physical dimensions of separation distress, loneliness, or grief in humans also look somewhat different from those of fear. Separation distress feels like bodily weakness, a “lump in the throat”, an inclination to cry tears, and a yearning to be comforted or to be near the lost loved one. Fear is more like intense muscle tension, fast heart rate, fast jumpy motions, and exaggerated startle reactions.

This suggests that mood problems in the “depression/anxiety” cluster need to be disambiguated more than modern psychiatry usually does; some involve a longing for social connection (or despair at ever getting it), while others involve a sense of being in danger, and these are distinct types that need to be addressed differently.

Implications

Panksepp’s theory of “basic” emotions makes a few opinionated claims.

Emotions are responses to survival-relevant situations, common to many species. That means they are not:

purely consequences of cognitive thoughts (you can still have emotions with no cortex and thus probably no ability to “think” in a rational human sense)

purely “mental” and not physical (you can induce emotions with drugs and brain stimulation)

purely responses to internal sensations or self-generated.actions, as William James believed

Instead, emotions can be modified in multiple ways: most obviously through change in the external situation; to a limited degree by top-down control (e.g. telling yourself or deciding to change an emotion), to a stronger degree by experiential learning (e.g. we acquire or lose fears by learning about what is and isn’t dangerous), and sometimes very directly through drug, surgical, or brain-stimulation intervention.

Because basic emotions are shared across species, we can get some sense of what these emotions are “for” evolutionarily, and what simple animal situations are the analogues for more complex human situations that trigger emotions.

Human-specific abilities like speech do have special dedicated regions of the cortex, but the cortex is exceedingly flexible; it is possible to remap other parts of it for language if Wernicke’s or Broca’s areas are damaged. The cortex does not really lend itself to absolute, crisp “this region does that thing” divisions as neuroscientists once hoped.

Hunting has sometimes been lumped in with animal “aggression” but it’s clearly more driven by SEEK than RAGE. Regions (like the lateral hypothalamus) that, when electrically stimulated, make predators (typically cats) hunt more are also always regions that the animals will choose to self-stimulate if given the opportunity. This, along with the relaxed, low-stress body language and physiology of a predator while hunting, indicates that hunting is probably subjectively pleasant for predators. They might experience it as “fun”, like a fascinating game.

Also, when animal domestication selects animals for “tameness”, aka low aggression towards humans, it does not reduce their hunting drive. This is further evidence that hunting and “defensive aggression” (fighting in response to perceived threat) are separate systems.

In fact, panic-attack patients on imipramine may feel like it’s done nothing for them, because they still suffer from the fear that they might have a panic attack — but if they actually track their panic attacks they might be surprised to learn that it’s been a long time since they’ve had one!

This was the author's claim -- thanks for the counter-evidence!