“I refuse to join any club that would have me as a member” -Marx[1]

Adverse Selection is the phenomenon in which information asymmetries in non-cooperative environments make trading dangerous. It has traditionally been understood to describe financial markets in which buyers and sellers systematically differ, such as a market for used cars in which sellers have the information advantage, where resulting feedback loops can lead to market collapses.

In this post, I make the case that adverse selection effects appear in many everyday contexts beyond specialized markets or strictly financial exchanges. I argue that modeling many of our decisions as taking place in competitive environments analogous to financial markets will help us notice instances of adverse selection that we otherwise wouldn’t.

The strong version of my central thesis is that conditional on getting to trade[2], your trade wasn’t all that great. Any time you make a trade, you should be asking yourself “what do others know that I don’t?” This does not mean that your trade is necessarily net bad, just that it is worse than it would have naively seemed before conditioning on having gotten to do the trade. The opportunity to trade is evidence that somebody else—in some cases, everybody else—passed over the decision to take that trade, or actively chose to take the other side of it.

This post is the first in a sequence on adverse selection, laying out my definition of the concept via a list of examples. The second post will discuss what factors determine the degree to which adverse selection is present in a given environment, and heuristics to detect them. The third will explore steps we can take to protect ourselves against adverse selection, as individuals and as a collective. The fourth will compare competitive and cooperative environments, the fifth will discuss a related claim that ambiguity obscures defection, and the sixth will connect to the concept of Goodharting and what levers of control we have over it.

Beware availability

When some options are taken and others are not, there may be a good reason for the difference in availability, even if that reason is not immediately obvious to you.

Alice’s Restaurant vs Bob’s Burgers

You’re on a road trip and passing through the exotic city of Teaneck, New Jersey, and decide to grab dinner at 7pm. The town has two diners: Alice’s Restaurant and Bob’s Burgers. From the outside, they look the same. Their menus are equally appealing. Since they seem tied on all other fronts, you default to alphabetical order, and go into Alice’s Restaurant. It’s packed to the brim, and you try to reserve a table, but they don’t have any openings for the next hour. So you go to Bob’s Burgers, order some food, and take a bite. The food is mediocre.

All else being equal, bad restaurants are more likely to have open tables than good restaurants. Alice's Restaurant and Bob's Burgers might look identical to you from the outside, but if all the tables at Alice's Restaurant are full and the tables at Bob's Burgers are open, that's evidence that Alice's Restaurant is better quality—and you'd rather eat there. Unfortunately for you, all the tables there are full, so you can't. The trades you get to do (eating at Bob's) are worse than the ones you don't (eating at Alice's).

That doesn't mean that eating at Bob's is worse than going hungry. It might still be worth buying food there instead of not at all. But next time, you might want to consider going at a less busy time, or making a reservation in advance.

The Parking Spot

Now that you’ve finished dinner, you continue on your road trip. Next stop: New York City. You begin the search for parking, and every spot seems to be taken. Each time you think you see a spot, there turns out to be a fire hydrant right next to it. You finally find an open spot in a convenient location, so you grab it. The next morning, you return and find a ticket on your car—apparently, Alternate Side Parking rules are in effect, something the locals all knew.

Without a story for why a parking spot in New York City hasn’t been taken, an opening should set off your alarms. My personal strategy to handle this is to drive around until I see someone pulling out of a spot—and then ask them why they’re leaving it, since parking spots are coveted resources not easily given up. Usually it’s because they have somewhere to be, and I can park comfortably knowing why the spot was free, but this has saved me from a ticket more than once when locals were pulling out only because Alternate Side Parking rules were about to go into effect.

The Suspiciously Empty Subway Car

Okay, to heck with cars, you decide to take the subway this time. You’re on the platform, and the train pulls into the station. Almost all of the subway cars are packed, but you notice one that is entirely empty. You’ll be able to get a seat! You step onto that car. The air conditioning is broken, and someone has defecated on the floor.

If it seems too good to be true, it might be because other subway riders know something you don’t. There’s a reason those seats are available—nobody else wants to be in that car. Unless you really don’t mind the heat and smell, you would have been better off boarding the busier car, and waiting for a seat to open at the next stop.

The Thanksgiving Leftovers

It’s the Sunday after Thanksgiving, and dinner is leftovers. You recall that your family’s Thanksgiving meal was delicious, so you’re excited to eat more of it. You get to the table, and find that you won’t be abel to get any meat—the only food left is Uncle Cain’s soggy fruit salad. All of the yummy food has disappeared over the weekend.

The best food at the Thanksgiving meal all got gobbled up on Thanksgiving. Of the leftovers, the better ones were eaten earlier in the weekend. The later you show up to Sunday night dinner, the worse the available options will be.

Beware models based on average values

If you model the world as providing you with a random sample, you’ll expect to get a better deal than if you correctly account for the fact that others have behaved and will behave in their own interest.

The Laffy Taffys

Laffy Taffys come in four flavors, three of which you really like. Your friend Drew is across the room next to the Laffy Taffy bowl, and you ask him to throw you a Laffy Taffy. (You don’t want to ask him for too big a favor, so you don’t specify flavor—you figure you’re 75% to get a good one anyway.) He reaches into the bowl and grabs a Laffy Taffy and tosses it to you. It’s Banana.

The mistake here is assuming that the Laffy Taffy is equally likely to be any of the four flavors. Laffy Taffys come in bags with equal distributions of the four flavors. If Drew drew from a brand new bag, you’d be 25% to get each of Sour Apple, Grape, Strawberry, or Banana. But he’s drawing from a bowl that people have been continuously taking Laffy Taffys out of. That means that you’re more than 25% to end up with Banana. (This is true even if there’s zero correlation between others’ preferences and your own, because you are one of the people who has been snacking on them.)

Ever wonder why the grapes at the end of the bowl are all squishy? It’s not only because they’ve been under the others (do grapes weigh enough for this to make a difference?). It’s also because the good ones get taken.

MoviePass

A typical moviegoer goes to the movie theaters less than once a month. The average price for a movie ticket is about $9. Here’s a business idea: charge users $10 a month for a service that gives them unlimited free tickets. What could go wrong?

Lowe dreaded the company's power users, those high-volume MoviePass customers who were taking advantage of the low monthly price, constantly going to the movies, and effectively cleaning the company out. According to the Motion Picture Association of America, the average moviegoer goes to the movies five times a year. The power users would go to the movies every day.

MoviePass users are selected for seeing a lot of movies. If MoviePass makes a business plan that models users as average people, it will lose a lot of money. Conditional on someone wanting to buy MoviePass, MoviePass probably should not want them as a customer.

Beware market orders

If you submit a market order (an order to buy or sell at the market's current best available price), you may get filled at a price that will make you unhappy.

The Field

You want to invest in real estate, so you go to your field-owning friend Ephron and submit a market order for his field.

You: I would like to buy your field.

Ephron: My man, it is all yours. Take it.

You: No, I want to pay dollars for it. I will pay whatever it costs. Which is how much, by the way?

Ephron: Oh, I guess, if I had to put a price on it, hrm, maybe $400 million? What’s $400 million between friends?

You: *gulp* Wow, that’s… a lot. I sure hope property value in this neighborhood rises over the next few thousand years. *hands over $400 million*

Ephrn: Thanks!

By giving Ephrn the option to sell the field to you at any price, you are opening yourself up to unlimited risk. He’s not going to choose a price that’s less than its true value, but he may choose a price that is more, potentially a lot more. Market orders are especially dangerous in illiquid markets, where there isn’t competition between providers. In this transaction, there was only one seller, so he got to set the price at whatever he wanted.

Never, ever, submit a market order in a competitive environment. You’re strictly better off submitting an IOC (immediate-or-cancel) limit order, i.e. an order which specifies the price above/below which you would not buy/sell.

I don't think this comes at the cost of much additional effort—I'm not advocating for calculating the exact EV, I'm claiming you are better off giving some limit, any limit (like, 2x, or even 10x, the price) than placing a true market order. This is pretty minimal extra effort for protecting you against various mistakes that will expose you to being adversely selected against—e.g. trading illiquid stock WDGT instead of the liquid stock WDGTS, in which you're not going to get filled at fair, you're going to get filled adversely at far higher prices in a market you did not intend to participate in and know nothing about.

If you’re worried about anchoring your counterparty to too high a number, as you might in the case of submitting a limit order with a high limit for a field purchase, you can write down your limit price and then still ask your counterparty to name a price, committing to only transact if it’s less than or equal to what you wrote down.

That said, I concede there are various situations, in particular cooperative interpersonal ones, where minimizing friction and signaling trust are valuable. It's probably pretty safe to say to a friend "can you grab me a banana from the store" (instead of "can you grab me a banana if and only if it costs less than $10") or "can you book a Lyft for me, I'll pay you back" (instead of "can you book a Lyft for me and I'll pay you back up to $500"). But even when you think you're in a cooperative environment, committing a potentially unbounded value ("we will reimburse travel costs") can result in counterparties optimizing on things they care about (comfort, convenience, the thrill of riding in a private jet) at the expense of your budget.

Beware sophisticated opponents

Know who you’re up against, what each of you are optimizing for (how correlated are your preferences?), and why they are taking their side of the trade.

The Juggling Contest

Your quantitative trading firm is holding its annual juggling tournament. Cost to enter is $18, winner takes all. You know you’re far better at juggling than most of your coworkers, so you sign up. As it turns out, only a few of your coworkers signed up, including Fortune, who used to be in the lucrative professional juggling world before leaving to pursue her lifelong passion of providing moderate liquidity to US Equities markets. You come in second place.

When signing up to compete in a zero-sum contest, assume your opponents are the best of the pool of possible competitors. They, too, had to run the mental exercise of “would I win my firm’s juggling contest?” You should have a story for why, despite that, you still think you’re likely to win.

You don’t have a way of knowing how good every single person at your firm is at juggling, so you need some algorithm for deciding whether you should compete. Say you have some juggling Elo score. One possible algorithm is “compete if and only if your Elo score is greater than or equal to 1600.”

Now, assume every person at the firm runs this algorithm to determine whether to compete. Here’s a strategy that dominates it: “Compete if and only if your Elo score is greater than or equal to 1601.” Why? Well, strategies A (>=1600) and B (>=1601) discriminate only in the event that your score is 1600. If everyone else follows strategy A, switching to strategy B either won’t affect whether you participate, or will cause you to not participate if your score is exactly 1600. In a world where all others use strategy A, you should prefer to not participate if your score is exactly 1600 (since at best, you tie in expectation). So if everyone is using A, you should switch from A to B. Your quantitative trading coworkers are also rational, so they will make the same switch.

Strategy A can only beat B if you have reason to believe that other people have lower thresholds than 1600 (in which case inclusion for 1600 may be positive). But someone in the pool has the lowest threshold, and that person would strictly improve by raising their threshold until it exceeds the second lowest participant’s. The person with the lowest threshold is making a mistake.[3] You should have a story for why you think that person isn’t you.

The Bedroom Allocation

You’re moving into a two-bedroom apartment with your roommate Grant. Grant was the one to find the apartment, and he gave you a virtual tour over zoom while he was there. You both like the apartment, so you put down a deposit. Now it’s time to decide on bedrooms, and Grant asks your preferences—if you both prefer the same room, you’ll rock-paper-scissors for it. Both rooms looked equally good to you on the zoom call, so you tell him that you’re indifferent. Grant chooses a room, and lo and behold, you find upon moving in that your room has less closet space and worse flooring. You feel a little crummy about the new arrangement.

Grant had information that you didn’t have, since he was able to see the room more clearly on his visit. Given the information gap, is there anything you could have done differently?

Here’s a strategy: instead of expressing indifference, you could have flipped a coin and chosen a room preference at random. This would have given you a 50% chance of selecting the better room (in which case you rock-paper-scissors), and a 50% chance of selecting the worse room. In all, that gives you a 25% chance of getting the better room. By leaving it up to Grant, you gave yourself a 0% chance of getting the better room.

Of course, there are a bunch of assumptions baked into this: that you and Grant have correlated preferences (generally true, but not always), that you prefer to maximize your own utility as opposed to the sum of both of your utilities, that you wouldn’t pay substantial social costs in the roommate dynamic as a result of doing something insane and cutthroat by normal-people-standards, et cetera. But there are many cases in which these assumptions do hold, so keeping a coin on you in case of emergency might pay dividends.

Beware beating the entire market

If you are in a liquid market and nevertheless you get to do a trade, you should wonder why nobody else wanted it.

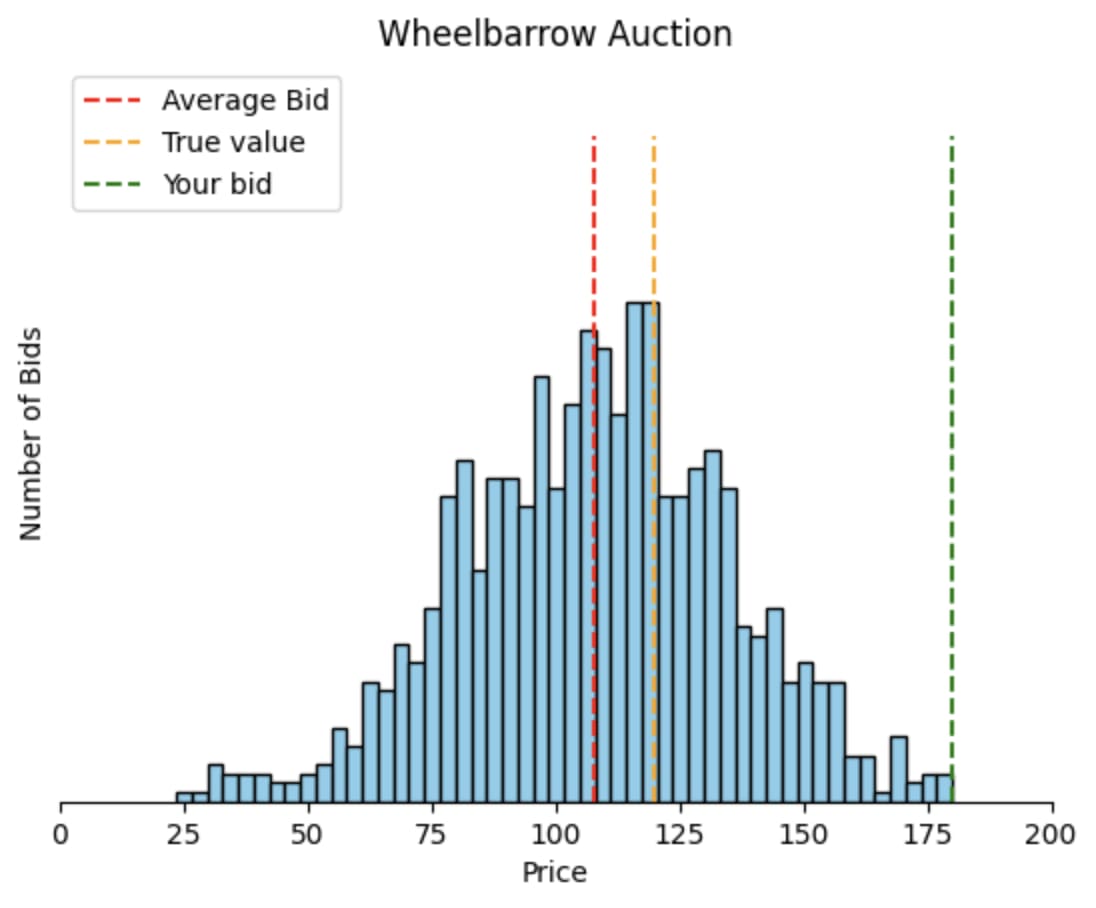

The Wheelbarrow Auction

This is an illustration of the winner’s curse.

At the town fair, a wheelbarrow is up for auction. You think the fair price of the wheelbarrow is around $200 (with some uncertainty), so you submit a bid for $180. You find out that you won the auction—everyone else submitted bids in the range of $25-$175, so your bid is the highest. After paying and taking your new acquisition home, you discover that the wheelbarrow is less sturdy than you’d estimated, and is probably worth more like $120. You check online, and indeed it retails for $120. You would have been better off buying it online.

Conditional on having won the auction, you outbid every single other participant. You are at the extreme tail of bids. The price you bid ($180) is a combination of your model of the wheelbarrow's price ($200, with some uncertainty) and the amount of edge you ask for to account for the winner's curse (10%, or $20).

If you are the winner, it means everybody else either models the price as lower, or asks for greater edge (i.e., adjusts down by a larger factor—in this case, I modeled everyone as adjusting down 10%, but adding noise to the adjustment factor is a better model that does not change the underlying effect), or some blend of the two.

If it's just because they're asking for a lot more edge, your bid could still be profitable in expectation. But it's likely some combination of the two, and the fact that their price models are all (or almost all) lower than yours should cause you to update that the true value of the wheelbarrow is lower than you'd previously estimated.

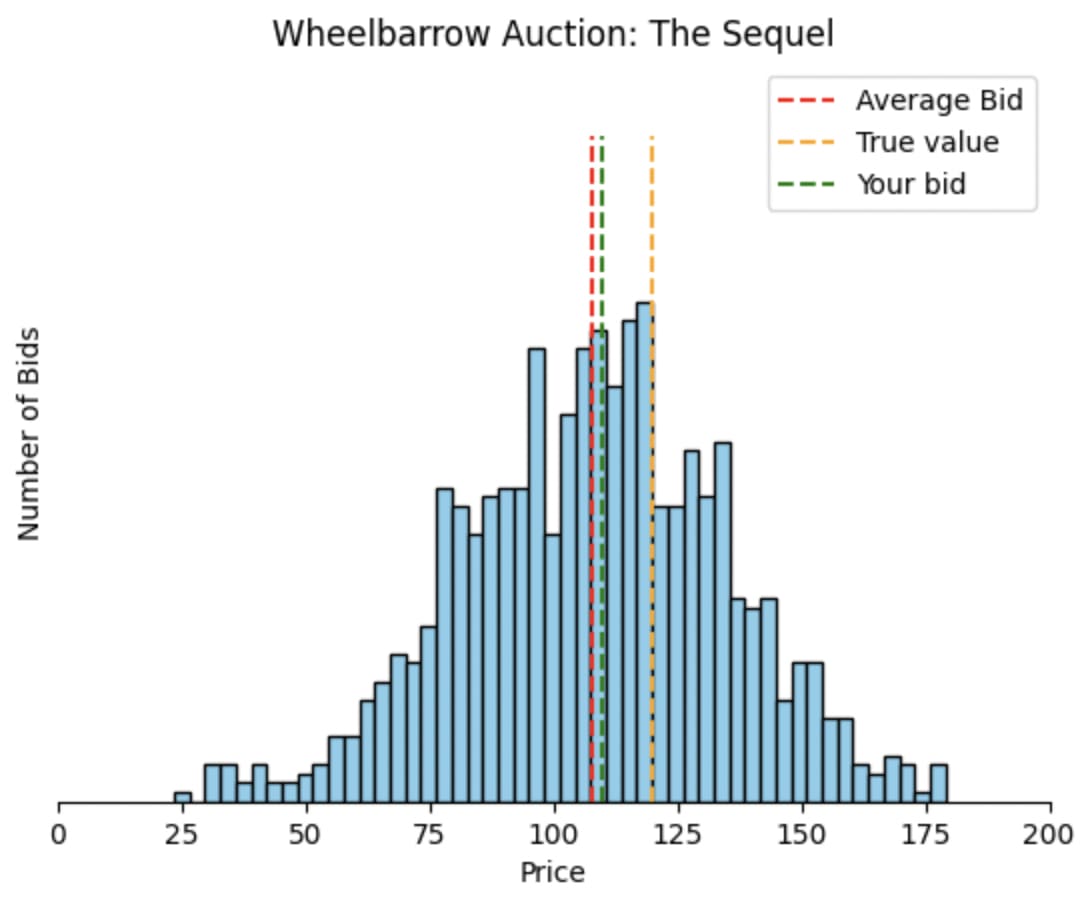

The Wheelbarrow Auction, part 2

At the town fair, a wheelbarrow is up for auction. You think the fair price of the wheelbarrow is around $120 (with some uncertainty), so you submit a bid for $108. You find out that you didn’t win—the winning bidder ends up being some schmuck who bid $180. You don’t exchange any money or wheelbarrows. When you get home, you check online out of curiosity, and indeed the item retails for $120. Your estimate was great, your bid was reasonable, and you exchanged nothing as a result, reaping a profit of zero dollars and zero cents.

In the previous example, your model was bad, you overestimated the true value, and as a result you lost money. In this example, your model was good—but you don’t profit, because you don’t end up winning the auction. There's an asymmetry between your profits when your model is correct and your losses when it is incorrect.

(Your model could also be bad in the downwards direction, and you think the wheelbarrow is worth a lot less, e.g. $25. In this case, you also don’t win the wheelbarrow, so your profit is $0.)

If the pool of bidders were much smaller, or their models were systematically biased downwards, or if they were more risk averse and asked for much more edge and as a result the worlds in which you outbid them but still profit outweigh worlds where you overshot, or if all the bidders agreed to collude and stuck to their agreement, or if you have sufficient reason to believe your model is extremely accurate (and theirs are not), you can still make money in an auction of this form. But your strong prior should be that you will not.

Beware the stock market

Only send orders that you would be happy with conditional on getting filled.

Widgets, Inc

Your local Widgets factory is rumored to have an upcoming merger. If the merger goes through, the stock will be worth $100. If it doesn’t, it’ll tank down to $0. Historically, you know that 80% of rumored mergers end up going through, so you believe that stock in Widgets Inc. should be worth $80.

As a result, you put out two orders in the market for WDGTS: a bid to buy the stock for $79 and an offer to sell the stock at $81. Both of these orders are good to your best estimate of the stock’s true value: if somebody traded with you at random, you’d make a dollar in expectation (either you buy stock worth $80 for a price of $79, or you sell stock worth $80 at a price of $81).

But other people are not trading with you at random—conditional on somebody trading with you, they believe it is profitable for them to do so. They will only buy from you for a price of $81 if their model says the stock is worth more than $81. Maybe they’ve read the Widgets Inc. prospectus, maybe they factored in demand for widgets this season, maybe they just tried to estimate the percentage of rumored mergers that end up going through, but they used a different historical dataset from yours and got 85%, and as a result believe the deal is 85% to go through.

If you know that they think the deal is 85% to go through, you should probably update your model in light of theirs. You should now think the deal is somewhere between 80% and 85% to go through. It might be 82.5%, it might be 80.1%, it might be 84.9%. For any of these, though, your $81 sale is worse than if the probability were truly 80%, your original best estimate. Once you know that, you should expect to make less than $1 in expected profit and reconsider what trades you want to do.

But, importantly, you only find out that they think your model is wrong once they trade with you—they don’t want to tell you if they could just make money off you instead! In worlds where Widgets stock is really worth more than $80, traders are more likely to buy from you. In worlds where Widgets stock is really worth less than $80, traders are more likely to sell to you. Conditional on one of your orders getting filled, your model of the world shifts in the direction that makes your trade less profitable than your old model would have predicted.

If someone buys from you for $81, you should not think “Great, I just made a dollar in expectation, I’m going to try to do the same trade again and see if someone else will also buy for $81!” You should think, “I wonder what they know that I don’t—it’s probably worth more than $80.”

- ^

Groucho Marx, specifically.

- ^

I will use the word “trade” expansively throughout to include any decision, agreement, plan, exchange, or the like that takes place in a competitive environment.

- ^

Alternatively, they’re paying money in expectation for the thrill of competitive juggling. That’s a fine utility function for them to have (people trade money for enjoyment all the time), and if you think others are doing this, there’s your story for why you should participate. Or you might be the juggling enjoyer—by all means, pay dollars to toss balls in the air for sport. This is normal and fine and a story (the most charitable story) for why casinos are in business.

MoviePass was paying full price for every ticket.