I have the same problem. I think my non-verbal IQ might be about 45 points above my verbal IQ, so that could be a factor. I also think mostly in concepts, since I'm afraid that thinking in words would blind me to insights which do not yet have words to describe them.

But translation from "idea in my mind" to "words that others can understand" is hard. I hear that information in the mind has a relational (mindmap) structure, while writing is linear and left-to-right. So the data structures are quite different.

I'm autistic, which harms my ability to communicate. I also tend to create my own vocabulary, and to use grammar in a mathematical sense. I might add "un-" or "-izable" affixes to words which shouldn't have them, or use set-builder notation in my personal notes, even if they contain no mathematics at all. This causes me to have my own efficient symbolic language which is incompatible with other peoples models/associations/tokens.

There's two other things I try to avoid:

1: Subvocalization (it slows me down)

2: Explaining things to myself. I know what I mean, always. If I catch myself thinking to myself as if other people were listening, I stop. Is this a natural habit meant to improving communication, or caused by trauma and fear of being misunderstood (like imagining social scenarios while in the shower)? For I imagine that it causes a dramatic reduction in thinking speed, even if you get the benefits of rubberducking.

In short, I'm guessing that people with high verbal intelligence, and those who tend to think purely in words don't have much difficulty writing. I don't have any contrary evidence in any of my memories, so I will believe this for now

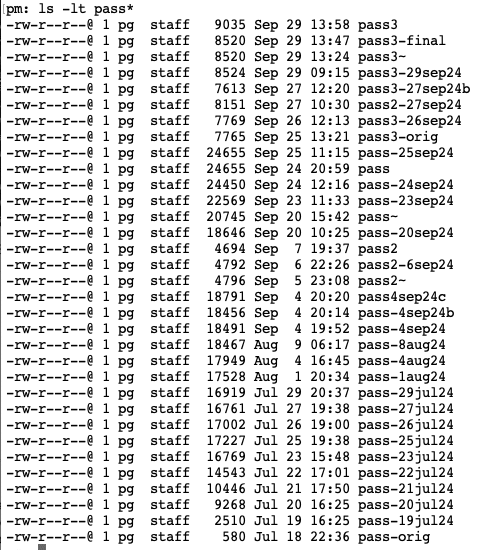

You are not alone. Paul Graham has been writing essays for a long time, and he is revising and rewriting a lot too. Here you can see him write one of his essays as an edit replay.

Also: "only one sentence in the final version is the same in the first draft."

Also:

The drafts of the essay I published today. This history is unusually messy. There's a gap while I went to California to meet the current YC batch. Then while I was there I heard the talk that made me write "Founder Mode." Plus I started over twice, most recently 4 days ago.

Yep! In fact, an earlier draft of this post included a mention of Paul Graham, because he's a popular and well-liked example of someone who has a similar process to the one I use (though I don't know if he does it for the same reasons).

In that earlier draft, I contrasted Graham with Scott Alexander, who I vaguely recall mentioning that he basically sits down at his computer and a couple hours later a finish piece of writing has appeared. But I couldn't find a good reference of this being Scott's process, so maybe it's just a thing I talked with him about in person one time.

In the end I decided this was an unnecessary tangent for the body of the text, but I'm very glad to have a chance to talk about it in the comments! Thanks!

I think what you are looking for is this:

People used to ask me for writing advice. And I, in all earnestness, would say “Just transcribe your thoughts onto paper exactly like they sound in your head.” It turns out that doesn’t work for other people. Maybe it doesn’t work for me either, and it just feels like it does.

and

I’ve written a few hundred to a few thousand words pretty much every day for the past ten years.

But as I’ve said before, this has taken exactly zero willpower. It’s more that I can’t stop even if I want to. Part of that is probably that when I write, I feel really good about having expressed exactly what it was I meant to say. Lots of people read it, they comment, they praise me, I feel good, I’m encouraged to keep writing, and it’s exactly the same virtuous cycle as my brother got from his piano practice.

(the included link is also directly relevant)

This post makes me feel better about my writing process. I write how I think, which means I can get away with little editing.

I find that surprising, given that so much of your writing feels kind of crisp and minimalist. Short punchy sentences. If that is how you think your mind is very unlike mine.

100% agreed. And you're definitely not alone. Someone once told me, when they asked me to describe the company I worked for, that "Your 5 minute pitch is much better than your 30 second pitch." The reasons are similar. And when I do try to condense and refine my language, I tend to run into the problem that most readers/listeners almost completely ignore qualifiers and caveats, however explicitly stated. I like to say that most of the meaning of a sentence is buried in the small words that are easy to ignore. It's very hard to express a web or network of meanings. That's also why people talk about "unpacking" and "close reading."

From CS Lewis, in the Space Trilogy:

“Of course I realise it’s all rather too vague for you to put into words,” when he took me up rather sharply, for such a patient man, by saying, “On the contrary, it is words that are vague. The reason why the thing can’t be expressed is that it’s too definite for language.”

And of course, from HPMOR ch 70:

Godric Gryffindor's autobiography had been a lot more compressed than the books Hermione was used to reading, he used one sentence to say things that should've taken thirty inches just by themselves, and then there was another sentence after that...

Many ideas are hard to fully express in words. Maybe no idea can be precisely and accurately captured. Something is always left out when we use our words.

What I think makes some people faster (and arguably better) writers is that they natively think in terms of communication with others, whereas I natively think in terms of world modeling, and then try to come up with words that explain the word model. They don't have to go through a complex thought process to figure out how to transmit their world model to others, because they just say thing that convey the messages that exist in their head, and those messages are generated based on their model of the world.

One funny thing I have noticed about myself is that I am bad enough at communicating certain ideas in speech that sometimes it is easier to handwave at what a couple things that I don't mean and let the listener figure out the largest semantic cluster in the remaining "meaning space".

I've written a lot of words—hundreds of blog posts, thousands of comments, tens of thousands of emails, and hundreds of thousands of short messages. I'm even written most of a book! In total, between personal and professional writing, I estimate to have put north of 3 million words into text. So it may come as a surprise that, despite all this experience, I still struggle to write well.

Sure, I've got the basics down, and when I put my mind to it I can achieve some measure of poetic prose. But to explain my ideas clearly, I still have to work quite hard for my writing to be understood.

Not all writers struggle with clarity. Some seem to be able to write exactly what they mean on the first pass and have their audience understand them. Others, like me, have to revise a lot, iterating over the same words dozens of times before they'll hang together. For example, it takes me about an hour to produce 100 words of finished text when I write about complex subjects, and I only speed up to 250 words/hour when the subject is simpler.

But what would happen if I didn't spend all that time revising? Would my writing really suffer that much?

It would.

Without extensive editing, my writing would be a jumbled mass of tangents, fragmented ideas, and confusing statements. You'd read my posts and probably think I said something I wouldn't endorse, or, worse yet, you'd give up reading me all together because it would take too much work. Thus I devote the time I must to editing for the simple reason that I want to convey ideas accurately and have people actually read them.

But why does my writing start out a mess? And why can't I do something, other than spend hours editing, to fix it? Because when my thoughts show up, they are like a scoop of spaghetti freshly dropped on a plate. The thought is definitely there, ready to be consumed, but the ideas are all tangled up, they don't combine to form a clear shape, and loose ends are left dangling over the side.

To be fair, my raw writing is not literally unintelligible, and sometimes people even like it because they like the ideas it contains. Still, it's not very good as writing. For example, here are some recent comments I made on Less Wrong that were written mostly stream-of-consciousness: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. The last one is particularly egregious and in desperate need of editing.

Words come out of me like they do because thoughts come into my mind as paragraph-sized gestalts. Writing my thoughts down is not impossible, but it requires great effort to convert them into specific words laid out in linear order. The task, for better and worse, is like taking a scoop of thought spaghetti off the plate, separating the noodles, wiping the sauce off, and then arranging them in neat rows on a new, clean plate.

It'd be nice if I could write how I think. I'd be able to share more of my ideas in less time, and I wouldn't have to devote so much mental effort to modeling how readers will interpret my words. Unfortunately, you wouldn't want to read anything I wrote that way. Every essay would be a miniature Infinite Jest, full of mixed-up narrative threads, abrupt asides, and random footnotes. And unlike David Foster Wallace and other difficult-to-read writers, few would power through my messy writing to understand it. So I've had to figure out how to say what I mean as clearly as I can and hope people will understand me.

I've developed a few strategies for writing over the years. They aren't very efficient, but they work reasonably well. They are:

I've also started using LLMs to help me write. One way I use them is to ramble my thoughts at them, then ask them to write a short version of what I said. Unfortunately, LLMs don't write great prose, so everything they produce requires editing. Luckily, I can use them to help me edit, too. I like to ask them for synonyms, alternative ways to phrase sentences, and examples to illustrate my points. They have allowed me quickly get unblocked on writing conundrums that previously took me days to solve.

But LLMs, so far, don't solve all my problems, and I'm still limited by my ability to express my ideas clearly enough to an LLM that it can figure out what I mean. So I struggle on with my spaghetti thoughts, laboriously converting them into words, working to fulfill my boundless desire to share what I've figured out with others.

Images created using DALLE-3. Thanks to Justis Mills for feedback.