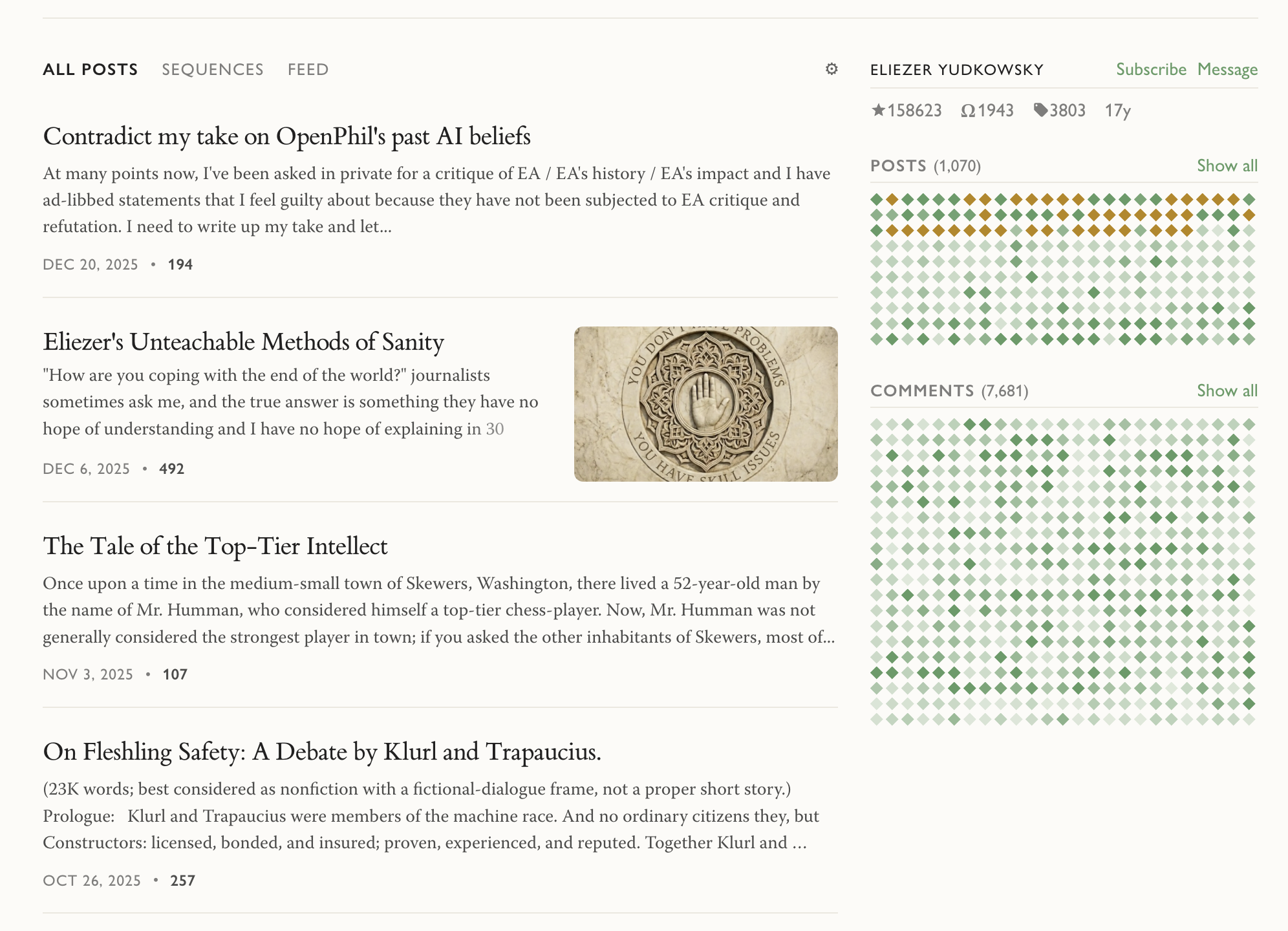

Feature update: I have added to the profile page a new highly-compressed overview of all of the user's LessWrong contributions!

- In the right sidebar you can find a single diamond for each post and for each comment that the user has written.

- Hovering over the post/comment lets you read it, and clicking opens it.

- The higher karma items are colored a darker shade of green. (Comments up to 50 karma, posts up to 100.)

- Posts that have been curated or that have passed the annual LW review, are gold/brown.

- It caps out at 250 posts and 500 comments, where you can click Show All to view the rest.

I currently think this is a very simple and visceral way to get a sense of someone's activity on LessWrong. As a bonus, it also makes pretty patterns :-)

My main concern with this is that it is too visually distracting from the content on the page, so I'll keep an eye out for that over the coming weeks and check if it feels like a big problem.

Again, the invitation is open for feedback/suggestions!

(In case anyone's wondering, I had been thinking of building something like this since Inkhaven, and I did not primarily build this in response to the comments on the new profile page, but I worked on it presently...

Maybe also add a link to the shortform (though mousehovering the first comment seems to work).

Please include a vote in your annual review comments! Often there are comments with mixed takes, or short comments with positive takes, but I don't know how it shapes up. Is this strong positive only a +4? Is this weakly positive actually a +9? Is this highly mixed review a -1 or a +9? It helps to know for many reasons (for example, does this person think I should be giving a different vote to my current one?).

This isn't literally always the right call, but I think it should probably be considered the default.

This seems backwards. Natural language review comments convey the substance of what people think; the one-dimensional review vote is an extremely lossy compression that only exists to help allocate reader attention and because we want to make it a competition. NLP tech is basically good enough already that in the future, you should do away with manual voting altogether: just embed the review comments into latent space, and let people project out a ranking along some dimension of interest if they want a ranking.

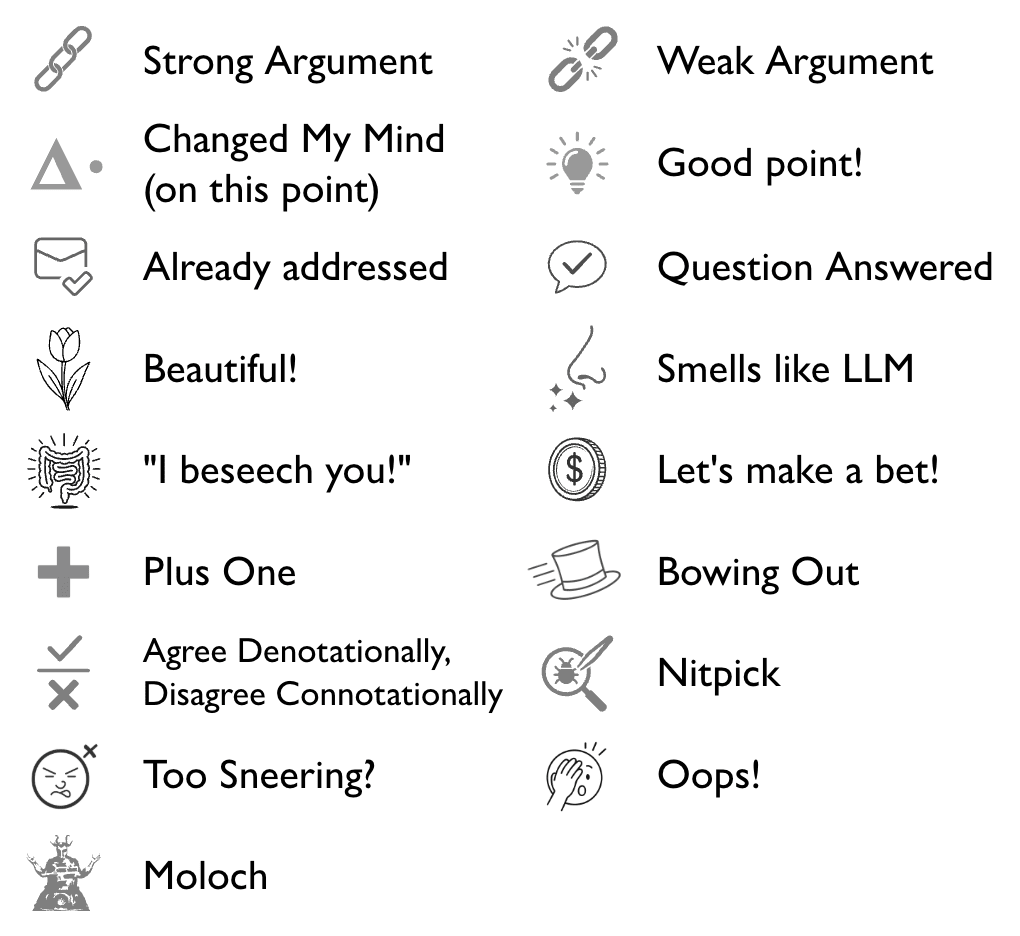

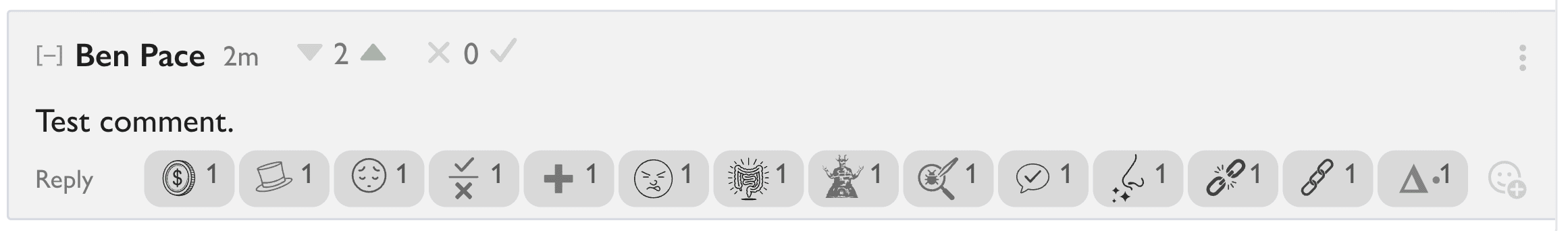

Announcing new reacts!

The reacts palette has 17 new reacts:

Gone are 11 old reacts who were getting little use, are redundant with the new reacts, and/or in my opinion weren't being used well (for example, "I'd bet this is false" almost never turned into a bet as I'd hoped, but was primarily used to disagree with added emphasis).

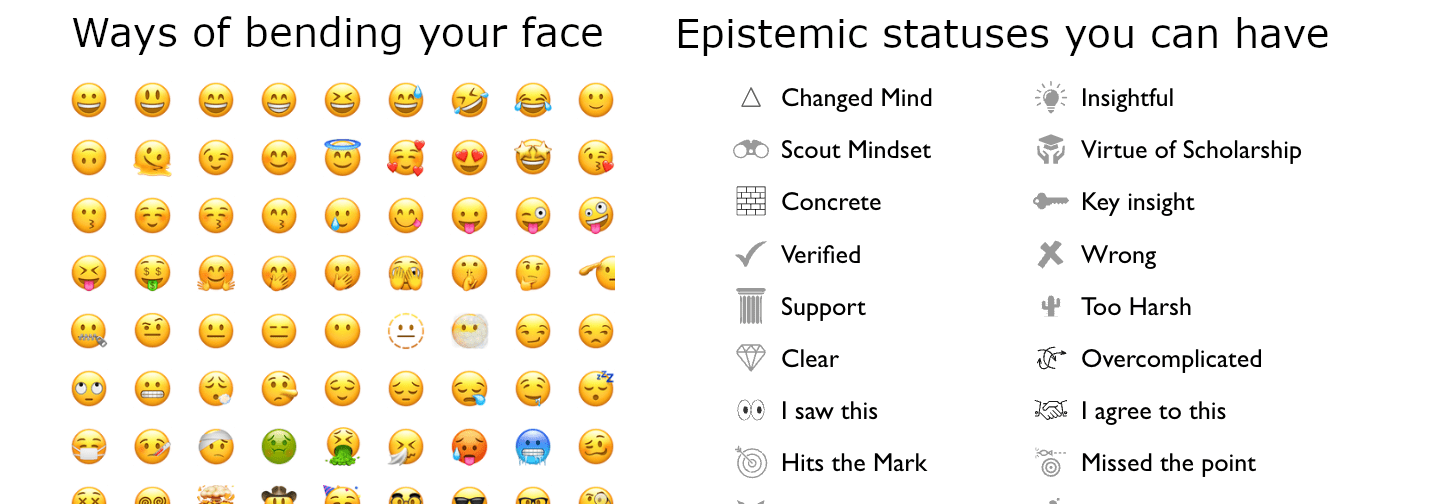

Reacts are a rich way to interact with a body of text, allowing many people to give information about comments, claims, and subclaims more efficiently than writing full comments, and they're something I love that we have on LessWrong (kudos to Raemon for building them initially!). They're also a way that people learn our culture – I will re-use Jimrandomh's classic meme on this topic.

I encourage you to look out for opportunities to use theses new reacts in the coming weeks, to give them a shot at life! We shall see which of these reacts get good use, and whether the use is good for truthseeking. I expect some of them will not, and will later be replaced by even newer reacts.

Feedback on the new reacts is invited, as are proposals for other reacts potentially worth adding.

P.S. There is also a stub of a wiki page on reacts, I would love it if people filled it o...

I am kind of interested in limiting the use of that react to once-per-month, so that it really means something when it gets used. Not sure whether to actually try this.

Answers! Of interest to: @Viliam @Raymond Douglas @Garrett Baker @Nina Panickssery @Perhaps @Mateusz Bagiński

Let's make a bet! |  Bowing Out |

Sad |  Agree Denotationally, Disagree Connotationally |

Plus One |  Too Sneering |

"I beseech you!" |  Moloch |

Nitpick |  Question Answered |

Smells like LLM |  Strong Argument |

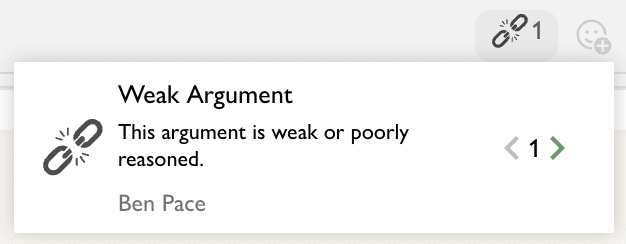

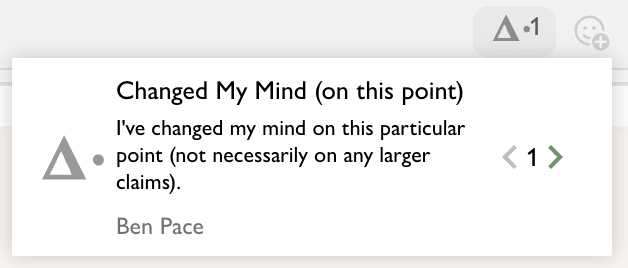

Weak Argument |  Changed My Mind (on this point) |

What do you mean here by "does not mean anything"?

It seems clear to me that there's some notion of off-the-record that journalists understand.

This might vary on details, and I agree is probably not legally binding, but it does seem to mean something.

I occasionally get texts from journalists asking to interview me about things around the aspiring rationalist scene. A few notes on my thinking and protocols for this:

- I generally think it is pro-social to share information with serious journalists on topics of clear public interest.

- By-default I speak with them only if their work seems relatively high-integrity. I like journalists whose writing is (a) factually accurate, (b) boring, and (c) do not feel to me to have an undercurrent of hatred for their subjects.

- By default I speak with them off-the-record, and then offer to send them write-ups of the things I said that they want to quote. This has gone quite well. I've felt comfortable speaking in my usual fashion without worrying about nailing each and every phrasing. Then I ask what they're interested in quoting, and I send them (typically a 1-2 page) google doc on those topics (largely re-stating what I already said to them, and making some improvements / additions). Then they tell me which quotes they want to use (typically cutting many sentences or paragraphs half-way). Then I make one or two slight edits and give them explicit permission to quote. I think this has gone quite wel

An idea I've been thinking about for LessOnline this year, is a blogging awards ceremony. The idea being that there's a voting procedure on the blogposts of the year, in a bunch of different categories, a shortlist is made and winners are awarded a prize.

I like opportunities for celebrating things in the online, written, truth-seeking ecosystem. I'm interested in reacts on whether people would be pro something like this happening, and comments on suggestions for how to do it well. (Epistemic status: tentatively excited about this idea.)

Here's my first idea for what the categories would be this year.

- Blog of the year

- Best original contribution (e.g. novel discovery, did some science, etc)

- Best explanation of a complex idea

- Biggest mistake admitted (H/T @ymekshout for suggesting this one)

- Best fiction

- Best counter-argument

- Best prediction

- Most productive dialogue

- Most beautiful non-fiction

- Best new blog

As for structure, I'm not really sure. Here's my first idea.

- How to nominate? Anyone can nominate a blogpost for $10. Anyone with a LessOnline ticket gets a free nomination. Anything published in 2024 is eligible.

- How is it judged? For the first year I'd probably keep it small and simple, pe

Something a little different: Today I turn 28. If you might be open to do something nice for me for my birthday, I would like to request the gift of data. I have made a 2-4 min anonymous survey about me as a person, and if you have a distinct sense of me as a person (even just from reading my LW posts/comments) I would greatly appreciate you filling it out and letting me know how you see me!

It's an anonymous survey where you rate me on lots of attributes like "anxious", "honorable", "wise" and more. All multiple-choice. Two years ago I al...

I have a general belief that internet epistemic hygiene norms should include that, when you quote someone, not only should you link to the source, but you should link to the highlight of that source. In general, if you highlight text on a webpage and right-click, you can "copy link to highlight" which when opened scrolls to and highlights that text. (Random example on Wikipedia.)

Further on this theme, archive.is has the interesting feature of constantly altering the URL to point to the currently highlighted bit of text, making this even easier. (Example, and you can highlight other bits of text to see it change.) Currently I overall don't like it because I constantly highlight text while I'm reading it, and so am v annoyed by the URL constantly changing, but it's plausible I'd get over this in time, and it'd be a good feature to add to LW.

The archive.is feature is also better because the normal "copy link to highlight" can often be unwieldily and long. Also I recall it sometimes not working, probably because the highlight is too short or too long (I don't quite understand the rules). On archive.is it just has a start and end number for where in the text is highlighted, making it al...

I have misgivings about the text-fragment feature as currently implemented. It is at least now a standard and Firefox implements reading text-fragment URLs (just doesn't conveniently allow creation without a plugin or something), which was my biggest objection before; but there are still limitations to it which show that a lot of what the text-fragment 'solution' is, is a solution to the self-inflicted problems of many websites being too lazy to provide useful anchor IDs anywhere in the page. (I don't know how often I go to link a section of a blog post, where the post is written in a completely standard hierarchical table-of-contents way, and the headers turn out to be... nothing but <h2>s with not an id= anywhere in sight.) We would be a lot better off if pages had more meaningful IDs and selecting text did something like, pick the nearest preceding ID. (This could be implemented in LW2 or Gwern.net right now, incidentally. If the user selects some text, just search through the tree to find the first previous ID, and update the current browser-bar URL to URL#ID.)

Hacking IDs onto an unwilling page, whose author neither knows nor cares nor can even find out what IDs are in us...

"Copy link to highlight" is not available in Firefox. And while e.g. Bing search seems to automatically generate these "#:~:text=" links, I find they don't work with any degree of consistency. And they're even more affected by link rot than usual, since any change to the initial text (like a typo fix) will break that part of the link.

I want to contrast two perspectives on human epistemology I've been thinking about for over a year.

There's one school of thought about how to do reasoning about the future which is about naming a bunch of variables, putting probability distributions over them, multiplying them together, and doing bayesian updates when you get new evidence. This lets you assign probabilities, and also to lots of outcomes. "What probability do I assign that the S&P goes down, and the Ukraine/Russia war continues, and I find a new romantic partner?" I'll call this the "spreadsheets" model of epistemology.

There's another perspective I've been ruminating on which is about visualizing detailed and concrete worlds, in a similar way to if you hold a ball and ask me to visualize how it'll fall if you drop it, that I can see the world in full detail. This is more about loading a full hypothesis into your head, and into your anticipations. It's more related to Privileging the Hypothesis / Believing In / Radical Probabilism[1]. I'll call this the "cognitive visualization" model of epistemology.

These visualizations hook much more directly to my anticipations and motivations. When I am running after you to r...

So many people have lived such grand lives. I have certainly lived a greater life than I expected, filled with adventures and curious people. But people will soon not live any lives at all. I believe that we will soon build intelligences more powerful than us who will disempower and kill us all. I will see no children of mine grow to adulthood. No people will walk through mountains and trees. No conscious mind will discover any new laws of physics. My mother will not write all of the novels she wants to write. The greatest films that will be made have probably been made. I have not often viscerally reflected on how much love and excitement I have for all the things I could do in the future, so I didn't viscerally feeling the loss. But now, when it is all lost, I start to think on it. And I just want to weep. I want to scream and smash things. Then I just want to sit quietly and watch the sun set, with people I love.

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Do not go gentle into that good night, Dylan Thomas

I'm still fighting. I hope you can find the strength to too.

Because their words had forked no lightning they

I think we have the opposite problem: our words are about to fork all the lightning.

Thank you.

It does not currently look to me like we will win this war, speaking figuratively. But regardless, I still have many opportunities to bring truth, courage, justice, honor, love, playfulness, and other virtues into the world, and I am a person whose motivations run more on living out virtues rather than moving toward concrete hopes. I will still be here building things I love, like LessWrong and Lighthaven, until the end.

I Changed My Mind on Prison Sentencing.

I used to have the opinion that prison sentencing should be a disincentive proportional to the upside of the crime. The question I'd ask was "How much of a prison sentence would make the crime not worth it to people?" I tried to estimate the upside to the criminal, and what length of sentence would make the expected utility reliably turn out negative. I would sometimes discuss with people how long of a prison sentence they'd risk in order to get the upside of a crime, and use this as an input into how long I thought sentencing should be. However, I now think this was an error, for two reasons:

- Many criminals or norm-breakers are not doing something as clear-headed as an explicit expected-value calculation, they are often thinking with part of their mind that is relatively uncivilized (and perhaps desperate or hidden from much of their conscious mind). For instance, it is done impulsively, or it is a crime of passion.

- An Astral Codex Ten blogpost reiterated the common wisdom that length of sentencing has little effect on crime rate, and instead reliability of punishment has a much larger effect. The conclusion reads "Deterrence effects are so wea

I recall it heard claimed that a reason why financial crimes sometimes seem to have disproportionately harsh punishments relative to violent crimes is that financial crimes are more likely to actually be the result of a cost-benefit analysis.

List of posts that seem promising to me, that are about to fall out of the annual review in 10 mins because only I have voted on them:

Recently, I told a friend of mine that I'd been to a wedding. They asked how it was, and I said the couple clearly loved each other very much (as they made clear repeatedly in their speeches). My friend made a face like that I read as some kind of displeasure, a bit of a grimace. Since then, I've been wondering why that was.

I think it's a common occurrence, that people feel negatively about others openly expressing their love for something (a person, a piece of art, a place, etc). I'm pretty sure I've had this feeling myself, but I don't know why.

I can thi...

If that was your first statement, then there is a whiff of 'damning with faint praise'.

"So, how was the big wedding?" "...well, the couple clearly loves each other very much." "...I see. That bad, huh."

I've been re-reading tons of old posts for the review to remember them and see if they're worth nominating, and then writing a quick review if yes (and sometimes if no).

I've gotten my list of ~40 down to 3 long ones. If anyone wants to help out, here are some I'd appreciate someone re-reading and giving a quick review of in the next 2 days.

- To Predict What Happens, Ask What Happens by Zvi

- A case for AI alignment being difficult by Jessicata

- Alexander and Yudkowsky on AGI goals by Scott Alexander & Eliezer Yudkowsky

I was chatting with someone, and they said that a particular group of people seemed increasingly like a cult. I thought that was an unhelpful framing, and here's the rough argument I wrote for why:

- There's lots of group dynamics that lead a group of people to go insane and do unethical things.

- The dynamics around Bankman-Fried involve a lot of naivety when interfacing with an sociopath who was scamming people for billions of dollars on a massive scale.

- The dynamics around Leverage Research involved lots of people with extremely little savings and income in a

So, if someone said that both Singapore and the United States were "States" you could also provide a list of ways in which Singapore and the United States differ -- consider size, attitude towards physical punishment, system of government, foreign policy, and so on and so forth. However -- share enough of a family resemblance that unless we have weird and isolated demands for rigor it's useful to be able to call them both "States."

Similarly, although you've provided notable ways in which these groups differ, they also have numerous similarities. (I'm just gonna talk about Leverage / Jonestown because the FTX thing is obscure to me)

-

They all somewhat isolated people, either actually physically (Jonestown) or by limiting people's deep interaction with outsiders ("Leverage research" by my recollection did a lot of "was that a worthwhile interaction?")

-

They both put immense individual pressure on people, in most cases in ways that look deliberately engineered and which were supposed to produce "interior conversion". Consider leverage's "Debugging" or what Wikipedia says about the People's Temple Precursor of Jonestown: "They often involved long "catharsis" sessions in which members

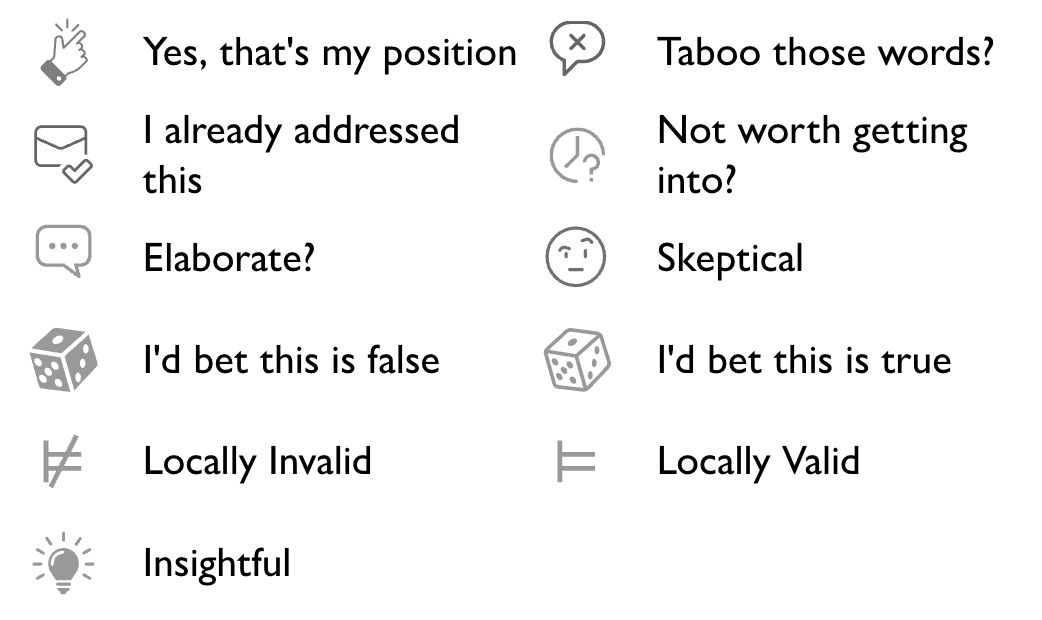

Two recent changes to LessWrong that I made!

- I have added two new reacts: "I'd bet this is false" and "I'd bet this is true".

- You can now sort a given user's comments by 'top' i.e. by karma.

For the first one, if you want to let someone know you'd be willing to take a bet (or if you want to call someone out on their bullshit) you can now highlight the claim they made and use the react. The react is a pair of dice, because we're never certain about propositions we're betting on (and because 'a hand offering money' was too hard to make out at the small scale). Hopefully this will increase people's affordance to take more bets on the site!

These reacts replaced "I checked it's true" and "I checked it's false", which didn't get that much use, but were some of the most abused reacts (often used on opinions or statements-of-positions that were simply not checkable).

For the second, if you go to a user profile and scroll down to the comments, you can now sort by 'top', 'newest', 'oldest', and 'recent replies'. I find that 'top' is a great way to get a sense of a person's thoughts and perspective on the world, and I used to visit greaterwrong a lot for this feature. Now you can do it on LessWrong!

Here's a quick list of 7 things people sometimes do instead of losing arguments, when it would be too personally costly to change their position.

- They pick a variable in the argument that is hard for the debaters to get closer to, and state that their raw-intuition is simply different to the person they're talking to. ("I just believe that human ingenuity will overcome problems like this, and you don't, and this isn't something we're easily going to be able to resolve." or "I think we're just not going to be able to resolve whether this city-wide intervention works or not without a good RCT.")

- They undermine your ability to have an opinion in the argument. ("I'm afraid there's very advanced research papers you'd need to read to have an understanding of this" or "You have been wrong so many times on so many issues, I don't think you're worth trusting on this one")

- They performatively don't understand basic ideas, or weaponize confusion. ("I'm sorry, could you explain your theory of 'ownership', I don't really understand what you mean when you say you own your company" or "I'm sorry, I'm not sure what it means to 'provoke'? I was just saying what I thought.")

- They get emotionally irate i

Schopenhauer's sarcastic essay The Art of Being Right (a manuscript published posthumously) goes in this direction. In it he suggests 38 rhetorical strategies to win a dispute by any means possible. E.g. your 3 corresponds to his 31, your 5 is similar to his 30, and your 7 to is similar his 18. Though he isn't just focusing on avoiding losing arguments, but on winning them.

Privacy: a tool for thinking for yourself

As part of some recent experiments with debates, today I debated Ronny Fernandez on the topic of whether privacy is good or bad, and I was randomly assigned the “privacy is good” side. I’ve cut a few excerpts together that I think work as a standalone post, and put them below.

At the start I was defending privacy in general, and then we found that our main disagreement was about whether it was helpful for thinking for yourself, so I focus even more on that after the opening statement.

This is an experiment. I'm down for feedback on whether to do more of this sort of thing (it only takes me ~2 hours), how I could make it better for the reader, whether to make it a top-level post, etc.

Epistemic status: soldier mindset. I will here be exaggerating the degree to which I believe my conclusions.

Opening Statement

My core argument is that, in general, the pressures for conformity amongst humans are crazy.

This is true of your immediate circle, your local community, and globally. Each one of these has sufficiently strong pressures that I think it is a good heuristic to actively keep secrets and things you think about and facts about your life separate fr...

I believe that when people write 'tap out' in comment sections, they are actually supposed to write 'bow out', in almost all cases I've read it.

I regularly see comment sections where someone, to indicate it's going to be their last comment, writes that they're 'tapping out' at this point. They rarely mean they're conceding the point, I'm pretty sure they're just respectfully ending their participation in the conversation. But that's not the standard meaning of the phrase in the place that it comes from.

Here's ChatGPT explaining the two phrases (emphasis added).

The phrase "tap out" originates from the world of combat sports, particularly Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and mixed martial arts (MMA). In these sports, a competitor signals submission or the desire to end a match by physically tapping their opponent, the mat, or even themselves. This act of tapping indicates that they can no longer continue the fight, either due to exhaustion, pain, or the risk of injury.

and

The phrase "bow out" means to gracefully or politely withdraw from a situation, activity, or role. It often implies a voluntary and dignified exit, often to avoid conflict or because it is the appropriate or respectful thing to do. The term can be used in various contexts, such as resigning from a job, ending participation in a project, or stepping down from a position of responsibility.

So I encourage any such people to change your usage accordingly!

Often I am annoyed when I ask someone (who I believe has more information than me) a question and they say "I don't know". I'm annoyed because I want them to give me some information. Such as:

"How long does it take to drive to the conference venue?"

"I don't know."

"But is it more like 10 minutes or more like 2 hours?"

"Oh it's definitely longer than 2 hours."

But perhaps I am the one making a mistake. For instance, the question "How many countries are there?" can be answered "I'd say between 150 and 400" or it can be answered "195", and the former is called "an estimate" and the latter is called "knowing the answer". There is a folk distinction here and perhaps it is reasonable for people to want to preserve the distinction between "an estimate" and "knowing the answer".

So in the future, to get what I want, I should say "Please can you give me an estimate for how long it takes to drive to the conference venue?".

And personally I should strive, when people ask me a question to which I don't know the answer, to say "I don't know the answer, but I'd estimate between X and Y."

I often wish I had a better way to concisely communicate "X is a hypothesis I am tracking in my hypothesis space". I don't simply mean that X is logically possible, and I don't mean I assign even 1-10% probability to X, I just mean that as a bounded agent I can only track a handful of hypotheses and I am choosing to actively track this one.

- This comes up when a substantially different hypothesis is worth tracking but I've seen no evidence for it. There's a common sentence like "The plumber says it's fixed, though he might be wrong" where I don't want to communicate that I've got much reason to believe he might be wrong, and I'm not giving it even 10% or 20%, but I still think it's worth tracking, because strong evidence is common and the importance is high.

- This comes up in adversarial situations when it's possible that there's an adversarial process selecting on my observations. In such situations I want to say "I think it's worth tracking the hypothesis that the politician wants me to believe that this policy worked in order to pad their reputation, and I will put some effort into checking for evidence of that, but to be clear I haven't seen any positive evidence for that hypothesi

For too long, I have erred on the side of writing too much.

The first reason I write is in order to find out what I think.

This often leaves my writing long and not very defensible.

However, editing the whole thing is so much extra work after I already did all the work figuring out what I think.

Sometimes it goes well if I just scrap the whole thing and concisely write my conclusion.

But typically I don't want to spend the marginal time.

Another reason my writing is too long is because I have extra thoughts I know most people won't find useful.

But I've picked up a heuristic that says it's good to share actual thinking because sometimes some people find it surprisingly useful, so I hit publish anyway.

Nonetheless, I endeavor to write shorter.

So I think I shall experiment with cutting the bits off of comments that represent me thinking aloud, but aren't worth the space in the local conversation.

And I will put them here, as the dregs of my cognition. I shall hopefully gather data over the next month or two and find out whether they are in fact worthwhile.

I don't normally just write-up takes, especially about current events, but here's something that I think is potentially crucially relevant to the dynamics involved in the recent actions of the OpenAI board, that I haven't seen anyone talk about:

The four members of the board who did the firing do not know each other very well.

Most boards meet a few times per year, for a couple of hours. Only Sutskever works at OpenAI. D'Angelo works senior roles in tech companies like Facebook and Quora, Toner is in EA/policy, and MacAulay at other tech companies (I'm not aware of any overlap with D'Angelo).

It's plausible to me that MacAulay and Toner have spent more than 50 hours in each others' company, but overall I'd probably be willing to bet at even odds that no other pair of them had spent more than 10 hours together before this crisis.

This is probably a key factor in why they haven't written more publicly about their decision. Decision-by-committee is famously terrible, and it's pretty likely to me that everyone pushes back hard on anything unilateral by the others in this high-tension scenario. So any writing representing them has to get consensus, and they're focused on firefighting and ge...

Did anyone else feel that when the Anthropic Scaling Policies doc talks about "Containment Measures" it sounds a bit like an SCP, just replaced with the acronym ASL?

...Item #: ASL-2-4

Object Class: Euclid, Keter, and Thaumiel

Threat Levels:

ASL-2... [does] not yet pose a risk of catastrophe, but [does] exhibit early signs of the necessary capabilities required for catastrophic harms

ASL-3... shows early signs of autonomous self-replication ability... [ASL-3] does not itself present a threat of containment breach due to autonomous self-replication, because it is both unlikely to be able to persist in the real world, and unlikely to overcome even simple security measures...

...an early guess (to be updated in later iterations of this document) is that ASL-4 will involve one or more of the following... [ASL-4 has] become the primary source of national security risk in a major area (such as cyberattacks or biological weapons), rather than just being a significant contributor. In other words, when security professionals talk about e.g. cybersecurity, they will be referring mainly to [ASL-4] assisted... attacks. A related criterion could be that deploying an ASL-4 system without safeguards

I've skimmed more than half of Anthropic's scaling policies doc. Key issues that stood out to me was the lack of incentive for any red-teamers to actually succeed at red-teaming. Perhaps I missed it, but I didn't see anything saying that the red-teamers had to necessarily not also have Anthropic equity. I also didn't see much other financial incentive for them to succeed. I would far prefer a world where Anthropic committed to put out a bounty of increasing magnitude (starting at like $50k, going up to like $2M) for external red-teamers (who signed NDAs) t...

"Slow takeoff" at this point is simply a misnomer.

Paul's position should be called "Fast Takeoff" and Eliezer's position should be called "Discontinuous Takeoff".

It is said that on this Earth there are two factions, and you must pick one.

- The Knights Who Arrive at False Conclusions

- The Knights Who Arrive at True Conclusions, Too Late to Be Useful

(Hat tip: I got these names 2 years ago from Robert Miles who had been playing with GPT-3.)

For the closing party of the Lightcone Offices, I used Midjourney 5 to make a piece of art to represent a LessWrong essay by each member of the Lightcone team, and printed them out on canvases. I'm quite pleased about how it came out. Here they are.

How I buy things when Lightcone wants them fast

by jacobjacob

(context: Jacob has been taking flying lessons, and someday hopes to do cross-country material runs for the Rose Garden Inn at shockingly fast speeds by flying himself to pick them up)

My thoughts on direct work (and joining LessWrong)

by RobertM

A Quick G

...I think I've been implicitly coming to believe that (a) all people are feeling emotions all the time, but (b) people vary in how self-aware they are of these emotions.

Does anyone want to give me a counter-argument or counter-evidence to this claim?

When I’m trying to become skillful in something, I often face a choice about whether to produce better output, or whether to bring my actions more in-line with my soul.

For instance, sometimes when I’m practicing a song on the guitar, I will sing it in a way where the words feel true to me.

And sometimes, I will think about the audience, and play in a way that is reliably a good experience for them (clear melody, reliable beat, not too irregular changes in my register, not moving in a way that is distracting, etc).

Something I just noticed is that it is somet...

I am still confused about moral mazes.

I understand that power-seekers can beat out people earnestly trying to do their jobs. In terms of the Gervais Principle, the sociopaths beat out the clueless.

What I don't understand is how the culture comes to reward corrupt and power-seeking behavior.

One reason someone said to me is that it's in the power-seekers interest to reward other power-seekers.

Is that true?

I think it's easier for them to beat out the earnest and gullible clueless people.

However, there's probably lots of ways that their sociopathic underlings ...

Striking paragraph by a recent ACX commenter (link):

I grew up surrounded by people who believed conspiracy theories, although none of those people were my parents. And I have to say that the fact that so few people know other people who believe conspiracy theories kind of bothers me. It's like their epistemic immune system has never really been at risk of infection. If your mind hasn't been very sick at least sometimes, how can you be sure you've developed decent priors this time?

Sometimes a false belief about a domain can be quite damaging, and a true belief can be quite valuable.

For example, suppose there is a 1000-person company. I tend to think that credit allocation for the success of the company is heavy tailed, and that there's typically 1-3 people who the company just would zombify and die without, and ~20 people who have the key context and understanding that the 1-3 people can work with to do new and live things. (I'm surely oversimplifying because I've not ever been on the inside with a 1000-person company.) In this situation it's very valuable to know who the people are who deserve the credit allocation. Getting the wrong 1-3 people is a bit of a disaster. This means that discussing it, raising hypotheses, bringing up bad arguments, bringing up arguments due to motivated cognition, and so on, can be unusually costly, and conversations about it can feel quite fraught.

Other fraught topics include breaking up romantically, quitting your job, leaving a community club or movement. I think taboo tradeoffs have a related feeling, like bringing up whether to lie in a situation, whether to cheat in a situation, or when to exchange money for values ...

Okay, I’ll say it now, because there’s been too many times.

If you want your posts to be read, never, never, NEVER post multiple posts at the same time.

Only do that if you don’t mind none of the posts being read. Like if they’re all just reference posts.

I never read a post if there’s two or more to read, it feels like a slog and like there’s going to be lots of clicking and it’s probably not worth it. And they normally do badly on comments on karma so I don’t think it’s just me.

Even if one of them is just meant as reference, it means I won’t read the other one.

Er, Wikipedia has a page on misinformation about Covid, and the first example is Wuhan lab origin. Kinda shocked that Wikipedia is calling this misinformation. Seems like their authoritative sources are abusing their positions. I am scared that I'm going to stop trusting Wikipedia soon enough, which is leaving me feeling pretty shook.

I'm thinking about the rigor of alternating strategies. Here are three examples.

- Forward-Chaining vs Backward-Chaining

- To be rich, don't marry for money. Surround yourself by rich people and marry for love. But be very strict about not letting poor people into your environment.

- Scott Garrabrant's once described his Embedded Agency research to me as the most back-chaining in terms of the area of work, and the most forward-chaining within that area. Often quite unable to justify what he's working on in the short-term (e.g. 1, 2, 3) yet can turn out to be very useful later on (e.g. 1).

- Optimism vs Pessimism

- Successful startup founders build a vision they feel incredible optimism and excitement about and are committed to making happen, yet falsify it as quickly as possible by building a sh*tty MVP and putting it in front of users, because you're probably wrong and the customer will show you what they want. Another name is "Vision vs Falsification".

- Finding vs Avoiding (Needles in Haystacks)

- Some work is about finding the needle, and some is about mining hay whilst ensuring that you avoid 100% of needles.

- For example when trying to build a successful Fusion Power Generator, most things yo

Something I've thought about the existence of for years, but imagined was impossible: this 70s song by Italian Adriano Celentano. It fully registers to my mind as English. But it isn't. It's like skimming the output of GPT-2.

Why has nobody noticed that the OpenAI logo is three intertwined paperclips? This is an alarming update about who's truly in charge...

I've been thinking lately that picturing an AI catastrophe is helped a great deal by visualising a world where critical systems in society are performed by software. I was spending a while trying to summarise and analyse Paul's "What Failure Looks Like", which lead me this way. I think that properly imagining such a world is immediately scary, because software can deal with edge cases badly, like automated market traders causing major crashes, so that's already a big deal. Then you add ML in, and can talk about how crazy it is to hand critical systems over

Hot take: The actual resolution to the simulation argument is that most advanced civilizations don't make loads of simulations.

Two things make this make sense:

- Firstly, it only matters if they make unlawful simulations. If they make lawful simulations, then it doesn't matter whether you're in a simulation or a base reality, all of your decision theory and incentives are essentially the same, you want to take the same decisions in all of the universes. So you can make lots of lawful simulations, that's fine.

- Secondly, they will strategically choose to not mak

There's a game for the Oculus Quest (that you can also buy on Steam) called "Keep Talking And Nobody Explodes".

It's a two-player game. When playing with the VR headset, one of you wears the headset and has to defuse bombs in a limited amount of time (either 3, 4 or 5 mins), while the other person sits outside the headset with the bomb-defusal manual and tells you what to do. Whereas with other collaboration games, you're all looking at the screen together, with this game the substrate of communication is solely conversation, the other person is providing all of your inputs about how their half is going (i.e. not shown on a screen).

The types of puzzles are fairly straightforward computational problems but with lots of fiddly instructions, and require the outer person to figure out what information they need from the inner person. It often involves things like counting numbers of wires of a certain colour, or remembering the previous digits that were being shown, or quickly describing symbols that are not any known letter or shape.

So the game trains you and a partner in efficiently building a shared language for dealing with new problems.

More than that, as the game gets harder, often

Good posts you might want to nominate in the 2018 Review

I'm on track to nominate around 30 posts from 2018, which is a lot. Here is a list of about 30 further posts I looked at that I think were pretty good but didn't make my top list, in the hopes that others who did get value out of the posts will nominate their favourites. Each post has a note I wrote down for myself about the post.

- Reasons compute may not drive AI capabilities growth

- I don’t know if it’s good, but I’d like it to be reviewed to find out.

- The Principled-Intelligence Hypothesis

- Very interesting hypothesis generation. Unless it’s clearly falsified, I’d like to see it get built on.

- Will AI See Sudden Progress? DONE

- I think this post should be considered paired with Paul’s almost-identical post. It’s all exactly one conversation.

- Personal Relationships with Goodness

- This felt like a clear analysis of an idea and coming up with some hypotheses. I don’t think the hypotheses really captures what’s going on, and most of the frames here seem like they’ve caused a lot of people to do a lot of hurt to themselves, but it seemed like progress in that conversation.

- Are ethical asymmetries from property rights?

- Again, another very intere

Trying to think about building some content organisations and filtering systems on LessWrong. I'm new to a bunch of the things I discuss below, so I'm interested in other people's models of these subjects, or links to sites that solve the problems in different ways.

Two Problems

So, one problem you might try to solve is that people want to see all of a thing on a site. You might want to see all the posts on reductionism on LessWrong, or all the practical how-to guides (e.g. how to beat procrastination, Alignment Research Field Guide, etc), or all the literature reviews on LessWrong. And so you want people to help build those pages. You might also want to see all the posts corresponding to a certain concept, so that you can find out what that concept refers to (e.g. what is the term "goodhart's law" or "slack" or "mesa-optimisers" etc).

Another problem you might try to solve, is that while many users are interested in lots of the content on the site, they have varying levels of interest in the different topics. Some people are mostly interested in the posts on big picture historical narratives, and less so on models of one's own mind that help with dealing with emotions and trauma. Som

At the SSC Meetup tonight in my house, I was in a group conversation. I asked a stranger if they'd read anything interesting on the new LessWrong in the last 6 months or so (I had not yet mentioned my involvement in the project). He told me about an interesting post about the variance in human intelligence compared to the variance in mice intelligence. I said it was nice to know people read the posts I write. The group then had a longer conversation about the question. It was enjoyable to hear strangers tell me about reading my posts.

Reading this post, where the author introspects and finds a strong desire to be able to tell a good story about their career, suggests that a way of understanding how people will make decisions will be heavily constrained by the sorts of stories about your career that are definitely common knowledge.

I remember at the end of my degree, there was a ceremony where all the students dressed in silly gowns and the parents came and sat in a circular hall while we got given our degrees and several older people told stories about how your children have become men and women, after studying and learning so much at the university.

This was a dumb/false story, because I'm quite confident the university did not teach these people most important skills for being an adult, and certainly my own development was largely directed by the projects I did on my own dime, not through much of anything the university taught.

But everyone was sat in a circle, where they could see each other listen to the speech in silence, as though it were (a) important and (b) true. And it served as a coordination mechanism, saying "If you go into the world and tell people that your child came to university and gre...

I think in many environments I'm in, especially with young people, the fact that Paul Graham is retired with kids sounds nice, but there's an implicit acknowledgement that "He could've chosen to not have kids and instead do more good in the world, and it's sad that he didn't do that". And it reassures me to know that Paul Graham wouldn't reluctantly agree. He'd just think it was wrong.

I was just re-reading the classic paper Artificial Intelligence as Positive and Negative Factor in Global Risk. It's surprising how well it holds up. The following quotes seem especially relevant 13 years later.

On the difference between AI research speed and AI capabilities speed:

The first moral is that confusing the speed of AI research with the speed of a real AI once built is like confusing the speed of physics research with the speed of nuclear reactions. It mixes up the map with the territory. It took years to get that first pile built, by a small group of physicists who didn’t generate much in the way of press releases. But, once the pile was built, interesting things happened on the timescale of nuclear interactions, not the timescale of human discourse. In the nuclear domain, elementary interactions happen much faster than human neurons fire. Much the same may be said of transistors.

On neural networks:

The field of AI has techniques, such as neural networks and evolutionary programming, which have grown in power with the slow tweaking of decades. But neural networks are opaque—the user has no idea how the neural net is making its decisions—and cannot easily be rendered...

I've finally moved into a period of my life where I can set guardrails around my slack without sacrificing the things I care about most. I currently am pushing it to the limit, doing work during work hours, and not doing work outside work hours. I'm eating very regularly, 9am, 2pm, 7pm. I'm going to sleep around 9-10, and getting up early. I have time to pick up my hobby of classical music.

At the same time, I'm also restricting the ability of my phone to steal my attention. All social media is blocked except for 2 hours on Saturday, whi...

I block all the big social networks from my phone and laptop, except for 2 hours on Saturday, and I noticed that when I check Facebook on Saturday, the notifications are always boring and not something I care about. Then I scroll through the newsfeed for a bit and it quickly becomes all boring too.

And I was surprised. Could it be that, all the hype and narrative aside, I actually just wasn’t interested in what was happening on Facebook? That I could remove it from my life and just not really be missing anything?

On my walk home from work today I realised that this wasn’t the case. Facebook has interesting posts I want to follow, but they’re not in my notifications. They’re sparsely distributed in my newsfeed, such that they appear a few times per week, randomly. I can get a lot of value from Facebook, but not by checking once per week - only by checking it all the time. That’s how the game is played.

Anyway, I am not trading all of my attention away for such small amounts of value. So it remains blocked.

I've found Facebook absolutely terrible as a way to both distribute and consume good content. Everything you want to share or see is just floating in the opaque vortex of the f%$&ing newsfeed algorithm. I keep Facebook around for party invites and to see who my friends are in each city I travel too, I disabled notifications and check the timeline for less than 20 minutes each week.

OTOH, I'm a big fan of Twitter. (@yashkaf) I've curated my feed to a perfect mix of insightful commentary, funny jokes, and weird animal photos. I get to have conversations with people I admire, like writers and scientists. Going forward I'll probably keep tweeting, and anything that's a fit for LW I'll also cross-post here.

I think of myself as pretty skilled and nuanced at introspection, and being able to make my implicit cognition explicit.

However, there is one fact about me that makes me doubt this severely, which is that I have never ever ever noticed any effect from taking caffeine.

I've never drunk coffee, though in the past two years my housemates have kept a lot of caffeine around in the form of energy drinks, and I drink them for the taste. I'll drink them any time of the day (9pm is fine). At some point someone seemed shocked that I was about to drink one a...

Responding to Scott's response to Jessica.

The post makes the important argument that if we have a word whose boundary is around a pretty important set of phenomena that are useful to have a quick handle to refer to, then

- It's really unhelpful for people to start using the word to also refer to a phenomena with 10x or 100x more occurrences in the world because then I'm no longer able to point to the specific important parts of the phenomena that I was previously talking about

- e.g. Currently the word 'abuser' describes a small number of people during some of their lives. Someone might want to say that technically it should refer to all people all of the time. The argument is understandable, but it wholly destroys the usefulness of the concept handle.

- People often have political incentives to push the concept boundary to include a specific case in a way that, if it were principled, indeed makes most of the phenomena in the category no use to talk about. This allows for selective policing being the people with the political incentive.

- It's often fine for people to bend words a little bit (e.g. when people verb nouns), but when it's in the class of terms w

I will actually clean this up and into a post sometime soon [edit: I retract that, I am not able to make commitments like this right now]. For now let me add another quick hypothesis on this topic whilst crashing from jet lag.

A friend of mine proposed that instead of saying 'lies' I could say 'falsehoods'. Not "that claim is a lie" but "that claim is false".

I responded that 'falsehood' doesn't capture the fact that you should expect systematic deviations from the truth. I'm not saying this particular parapsychology claim is false. I'm saying it is false in a way where you should no longer trust the other claims, and expect they've been optimised to be persuasive.

They gave another proposal, which is to say instead of "they're lying" to say "they're not truth-tracking". Suggest that their reasoning process (perhaps in one particular domain) does not track truth.

I responded that while this was better, it still seems to me that people won't have an informal understanding of how to use this information. (Are you saying that the ideas aren't especially well-evidenced? But they so...

The definitional boundaries of "abuser," as Scott notes, are in large part about coordinating around whom to censure. The definition is pragmatic rather than objective.*

If the motive for the definition of "lies" is similar, then a proposal to define only conscious deception as lying is therefore a proposal to censure people who defend themselves against coercion while privately maintaining coherent beliefs, but not those who defend themselves against coercion by simply failing to maintain coherent beliefs in the first place. (For more on this, see Nightmare of the Perfectly Principled.) This amounts to waging war against the mind.

Of course, in matter of actual fact we don't strongly censure all cases of consciously deceiving. In some cases (e.g. "white lies") we punish those who fail to lie, and those who call out the lie. I'm also pretty sure we don't actually distinguish between conscious deception and e.g. reflexively saying an expedient thing, when it's abundantly clear that one knows very well that the expedient thing to say is false, as Jessica pointed out here.

*It's not clear to me that this is a good kind of concept to ...

I recently circled for the first time. I had two one-hour sessions on consecutive days, with 6 and 8 people respectively.

My main thoughts: this seems like a great way for getting to know my acquaintances, connecting emotionally, and build closer relationships with friends. The background emotional processing happening in individuals is repeatedly brought forward as the object of conversation, for significantly enhanced communication/understanding. I appreciated getting to poke and actually find out whether people's emotional states matched the words they were using. I got to ask questions like:

When you say you feel gratitude, do you just mean you agree with what I said, or do you mean you're actually feeling warmth toward me? Where in your body do you feel it, and what is it like?

Not that a lot of my circling time was skeptical of people's words, a lot of the time I trusted the people involved to be accurately reporting their experiences. It was just very interesting - when I noticed I didn't feel like someone was honest about some micro-emotion - to have the affordance to stop and request an honest internal report.

It felt like there was a constant tradeoff betw...

Yesterday I noticed that I had a pretty big disconnect from this: There's a very real chance that we'll all be around, business somewhat-as-usual in 30 years. I mean, in this world many things have a good chance of changing radically, but automation of optimisation will not cause any change on the level of the industrial revolution. DeepMind will just be a really cool tech company that builds great stuff. You should make plans for important research and coordination to happen in this world (and definitely not just decide to spend everything on a last-ditch effort to make everything go well in the next 10 years, only to burn up the commons and your credibility for the subsequent 20).

Only yesterday when reading Jessica's post did I notice that I wasn't thinking realistically/in-detail about it, and start doing that.

Related hypothesis: people feel like they've wasted some period of time e.g. months, years, 'their youth', when they feel they cannot see an exciting path forward for the future. Often this is caused by people they respect (/who have more status than them) telling them they're only allowed a small few types of futures.

I talked with Ray for an hour about Ray's phrase "Keep your beliefs cruxy and your frames explicit".

I focused mostly on the 'keep your frames explicit' part. Ray gave a toy example of someone attempting to communicate something deeply emotional/intuitive, or perhaps a buddhist approach to the world, and how difficult it is to do this with simple explicit language. It often instead requires the other person to go off and seek certain experiences, or practise inhabiting those experiences (e.g. doing a little meditation, or getting in touch with their emotion of anger).

Ray's motivation was that people often have these very different frames or approaches, but don't recognise this fact, and end up believing aggressive things about the other person e.g. "I guess they're just dumb" or "I guess they just don't care about other people".

I asked for examples that were motivating his belief - where it would be much better if the disagreers took to hear the recommendation to make their frames explicit. He came up with two concrete examples:

- Jim v Ray on norms for shortform, where during one hour they worked through the same reasons

I find "keep everything explicit" to often be a power move designed to make non-explicit facts irrelevant and non-admissible. This often goes along with burden of proof. I make a claim (real example of this dynamic happening, at an unconference under Chatham house rules: That pulling people away from their existing community has real costs that hurt those communities), and I was told that, well, that seems possible, but I can point to concrete benefits of taking them away, so you need to be concrete and explicit about what those costs are, or I don't think we should consider them.

Thus, the burden of proof was put upon me, to show (1) that people central to communities were being taken away, (2) that those people being taken away hurt those communities, (3) in particular measurable ways, (4) that then would impact direct EA causes. And then we would take the magnitude of effect I could prove using only established facts and tangible reasoning, and multiply them together, to see how big this effect was.

I cooperated with this because I felt like the current estimate of this cost for this person was zero, and I could easily raise that, and that was better than nothing,...

One last bit is to keep in mind that most (or, many things), can be power moves.

There's one failure mode, where a person sort of gives you the creeps, and you try to bring this up and people say "well, did they do anything explicitly wrong?" and you're like "no, I guess?" and then it turns out you were picking up something important about the person-giving-you-the-creeps and it would have been good if people had paid some attention to your intuition.

There's a different failure mode where "so and so gives me the creeps" is something you can say willy-nilly without ever having to back it up, and it ends up being it's own power move.

I do think during politically charged conversations it's good to be able to notice and draw attention to the power-move-ness of various frames (in both/all directions)

(i.e. in the "so and so gives me the creeps" situation, it's good to note both that you can abuse "only admit explicit evidence" and "wanton claims of creepiness" in different ways. And then, having made the frame of power-move-ness explicit, talk about ways to potentially alleviate both forms of abuse)

To complement that: Requiring my interlocutor to make everything explicit is also a defence against having my mind changed in ways I don't endorse but that I can't quite pick apart right now. Which kinda overlaps with your example, I think.

I sometimes will feel like my low-level associations are changing in a way I'm not sure I endorse, halt, and ask for something that the more explicit part of me reflectively endorses. If they're able to provide that, then I will willingly continue making the low-level updates, but if they can't then there's a bit of an impasse, at which point I will just start trying to communicate emotionally what feels off about it (e.g. in your example I could imagine saying "I feel some panic in my shoulders and a sense that you're trying to control my decisions"). Actually, sometimes I will just give the emotional info first. There's a lot of contextual details that lead me to figure out which one I do.

I'd been working on a sequence explaining this all in more detail (I think there's a lot of moving parts and inferential distance to cover here). I'll mostly respond in the form of "finish that sequence."

But here's a quick paragraph that more fully expands what I actually believe:

- If you're building a product with someone (metaphorical product or literal product), and you find yourself disagreeing, and you explain "This is important because X, which implies Y", and they say "What!? But, A, therefore B!" and then you both keep repeating those points over and over... you're going to waste a lot of time, and possibly build a confused frankenstein product that's less effective than if you could figure out how to successfully communicate.

- In that situation, I claim you should be doing something different, if you want to build a product that's actually good.

- If you're not building a product, this is less obviously important. If you're just arguing for fun, I dunno, keep at it I guess.

- A separate, further claim is that the reason you're miscommunicating is because you have a bunch of hidden assumptions in yo

every time you disagree with someone about one of your beliefs, you [can] automatically flag what the crux for the belief was

This is the bit that is computationally intractable.

Looking for cruxes is a healthy move, exposing the moving parts of your beliefs in a way that can lead to you learning important new info.

However, there are an incredible number of cruxes for any given belief. If I think that a hypothetical project should accelerate it's development time 2x in the coming month, I could change my mind if I learn some important fact about the long-term improvements of spending the month refactoring the entire codebase; I could change my mind if I learn that the current time we spend on things is required for models of the code to propagate and become common knowledge in the staff; I could change my mind if my models of geopolitical events suggest that our industry is going to tank next week and we should get out immediately.

Hypothesis: power (status within military, government, academia, etc) is more obviously real to humans, and it takes a lot of work to build detailed, abstract models of anything other than this that feel as real. As a result people who have a basic understanding of a deep problem will consistently attempt to manoeuvre into powerful positions vaguely related to the problem, rather than directly solve the open problem. This will often get defended with "But even if we get a solution, how will we implement it?" without noticing that (a) there is no real effort by anyone else to solve the problem and (b) the more well-understood a problem is, the easier it is to implement a solution.

I'd take a bet at even odds that it's single-digit.

To clarify, I don't think this is just about grabbing power in government or military. My outside view of plans to "get a PhD in AI (safety)" seems like this to me. This was part of the reason I declined an offer to do a neuroscience PhD with Oxford/DeepMind. I didn't have any secret for why it might be plausibly crucial.

Reviews of books and films from my week with Jacob:

Films watched:

- The Big Short

- Review: Really fun. I liked certain elements of how it displays bad nash equilibria in finance (I love the scene with the woman from the ratings agency - it turns out she’s just making the best of her incentives too!).

- Grade: B

- Spirited Away

- Review: Wow. A simple story, yet entirely lacking in cliche, and so seemingly original. No cliched characters, no cliched plot twists, no cliched humour, all entirely sincere and meaningful. Didn’t really notice that it was animated (while fantastical, it never really breaks the illusion of reality for me). The few parts that made me laugh, made me laugh harder than I have in ages.

- There’s a small visual scene, unacknowledged by the ongoing dialogue, between the mouse-baby and the dust-sprites which is the funniest thing I’ve seen in ages, and I had to rewind for Jacob to notice it.

- I liked how by the end, the team of characters are all a different order of magnitude in size.

- A delightful, well-told story.

- Grade: A+

- Stranger Than Fiction

- Review: This is now my go-to film of someone trying something original and just failing. Filled with new ideas, but none executed well, a

The comments here are a storage of not-posts and not-ideas that I would rather write down than not.