The discovery and use of machinery may be … injurious to the labouring class, as some of their number will be thrown out of employment, and population will become redundant.

Fears about human labor getting replaced by machines go back hundreds if not thousands of years. These fears continue today in response to the rapid progress of AI in several previously secure human domains.

Rudolf L on the Lesswrong forum, for example, claims that a world with labor-replacing AI would mean:

- People's labour gives them less leverage than ever before.

- Achieving outlier success through your labour in most or all areas is now impossible.

Scott Alexander responded to this post with some reasons to doubt the implications of complete labor redundancy, but he accepts the premise that AGI will make human labor valueless without contest.

The basic argument in favor of this position is twofold. First, that AI will continue to rapidly automate tasks that humans used to do. Second, is that as a consequence of this automation, there will be more available labor available for a shrinking number of jobs, thus lowering wages until eventually all tasks are produced by AIs and the only way to make income is to own some GPUs, power plants, or land.

The long history of this idea proves that it is convincing but it probably isn’t true. Even if AGI continues to advance and is eventually able to do any task that humans currently do, human labor will not become worthless.

The Labor Share of GDP Has Been Constant For 200+ Years

The labor share of income - the fraction of total output that is paid to workers versus capital owners - has been constant for so long that it has become one of the fundamental regularities that any model of long run economic growth must explain. For at least 200 years, 50-60% of GDP has gone to pay workers with the rest paid to machines or materials. There is lots of hubbub about falling labor share since the 1990s, but this is due to mismeasurement of labor income which has shifted increasingly into non-wage benefits like employer healthcare and retirement plans. Accounting for this, the regularity of labor’s share of income at around 50% remains.

The basic story that motivates fear of AI automation predicts that more automation leads to lower value and leverage for labor, but this story cannot a explain a flat labor share of income since 1800. The past 200+ year period of industrial economic growth has been defined by the rapid growth of labor-replacing automation, but labor’s share of income has been constant. Almost all the tasks that were done by humans in 1800 are now automated, but the labor share of income did not go to zero. This is not to say that a change in labor’s share of GDP is impossible, but the constancy of this measure through all of our past experience with labor-replacing technologies is an important foundation to keep in mind when predicting the effects of the next such technology.

Labor’s constant share of income is not due to luck or coincidence but equilibrating forces in overall demand, relative factor prices, and directed technological change.

A technological innovation that automates tasks previously done by labor does displace people and decrease labor’s share of income. However, there are four countervailing effects which keep labor’s share constant.

- Automation increases productivity and output.

A task won’t be automated unless it increases productivity to do it with machines instead of labor. Therefore, once something is automated, people can afford more of the automated product at lower cost and their budget constraint is relaxed everywhere else, essentially increasing their total incomes.

When incomes increase, people demand more goods from all sectors, including the sector getting automated and other labor intensive sectors. If demand for the good produced by the automated tasks is very elastic, this can even increase employment in the automated sector. For example, the printing press automated the most labor intensive part of authorship, but the increase in the quantity of books demanded was so great that in addition to each author getting hundreds of times more productive, there was also an explosion in the number of people employed as authors after the printing press automated away many of their tasks.

Alternatively, the productivity increase will have spillovers into demand for other areas of the economy that aren’t as easily automated. For example, as farming was mechanized and automated, people didn’t need to spend as much on food, so their incomes effectively increased. While they didn’t spend enough extra money on food to offset labor displacement there, they spent enough on other industries like textiles and automobiles which employed more labor to meet that demand. - Automation raises the amount of capital available to each worker.

Automation makes capital more productive, thus raising the returns to investment and leading people to build more capital machines. This increase in the capital stock complements labor and makes it more productive, and thus better compensated.

For example, the automation of computing displaced many “computers”, but it made certain types of capital much more valuable. As firms invested in computers, the marginal worker became more productive since they now had access to powerful machines that helped them in their work. The rise in labor demand for more productive computer-powered secretaries, stock traders, engineers, and programmers far outweighed the displacement caused by the automation in the first place.

Additionally, since the supply of capital responds elastically to changes in its productivity while labor does not, the productivity gains from automation end up accruing to labor in a type of Baumol’s cost disease. - Automation often improves capital productivity

Automation can help capital replace a task that is currently done by labor, but it can also replace old capital and improve productivity in already automated tasks. For example, the transition from horse-drawn plows to tractors doesn't have any displacement effect but does have an income effect, which again increases demand for all goods including from labor intensive sectors or sectors where labor has a comparative advantage, thus increasing wages and employment in those sectors. - Automation creates new tasks that labor can perform.

Automation often straightforwardly creates a new task for labor by requiring someone to produce, supervise, and maintain the automating machinery. Even when this is not the case, the displacement caused by automation also incentivizes more investment into technology which creates new tasks for labor rather than capital. Automation means that capital has a growing opportunity cost, while labor has a falling opportunity cost. There are more valuable tasks that capital can do and fewer that labor can. So a new technology which takes advantage of underutilized labor will get higher returns than one that relies on in-demand and constrained capital.

These forces have kept the labor share of income in equilibrium through all of the major technological revolutions of the past 200+ years. Therefore, a convincing and likely true story about how AI will automate most of the tasks currently performed by humans is insufficient evidence to conclude that the labor share of income will go to zero.

Self-Replicating Genius Labor Did Not Make Average Labor Worthless

The obvious response to the above argument is that AGI is different than all the labor replacing technology which came before it. These previous technologies automated particular, narrow tasks rather than emulating the general learning capacity of the human mind.

It may be true that labor can retain it’s value against capital that automates one task at a time, but what would happen if tens or hundreds of millions of fully general human-level general intelligences suddenly entered the labor market and started competing for jobs?

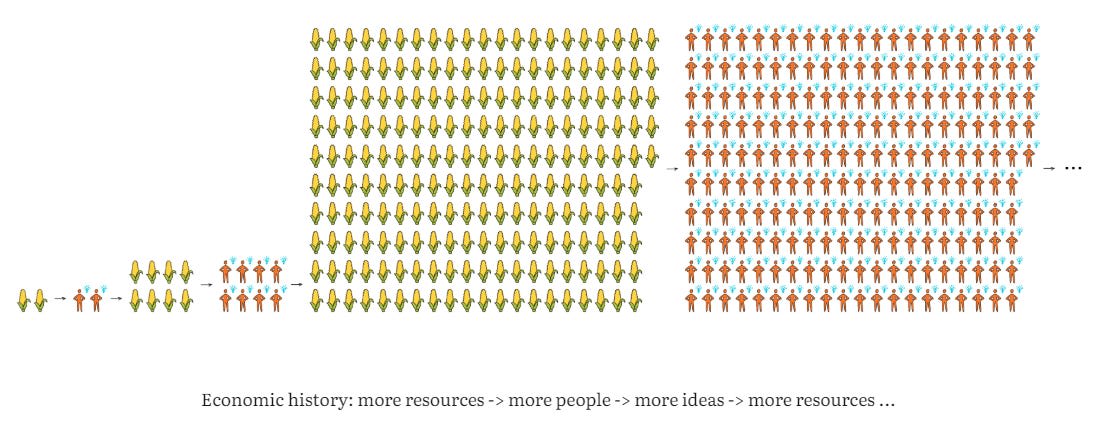

We needn’t speculate because this has already happened. Over the past three centuries, population growth, urbanization, transportation increases, and global communications technology has expanded the labor market of everyone on earth to include tens or hundreds of millions of extra people. This influx of intelligence came out of a recursively self-improving feedback loop between people, the ideas they create, the resource they can produce using those new ideas, and the new people those resources can support.

For below average intelligence laborers, this means competing with an ever-growing population of people who are better than them at any conceivable task. The amount of intelligence competing in the average person’s labor market increased by several orders of magnitude over the past few centuries.

But this did not turn low skilled laborers into a permanently unemployed underclass who could not make any money from their labor. In fact, their incomes increased a lot as they specialized and traded with these much more intelligent workers.

The reason for this is comparative advantage. Low skilled laborers are worse than high skilled ones at all tasks. But high-skilled laborers face constraints: if they work on an assembly line, they can’t also teach at the university. Low-skilled workers don’t face this tradeoff and thus can outcompete high-skilled workers for assembly line jobs even when they are less productive at them. Exactly because of their superior ability at all tasks, high skilled workers give up more when they choose to do something that they could trade for.

This applies just as strongly to human level AGIs. They would face very different constraints than human geniuses, but they would still face constraints. There would still not be an infinite or costless supply of intelligence as some assume. The advanced AIs will face constraints, pushing them to specialize in their comparative advantage and trade with humans for other services even when they could do those tasks better themselves, just like advanced humans do.

The idea that the labor share of income has been historically stable is often taken as a given, but it’s more of a “stylized fact” than an unchanging law. Measuring non-wage compensation, like healthcare and retirement benefits, is notoriously tricky, which makes it hard to get a clear picture. And if capital—like machines and software—ever becomes a perfect substitute for human labor, that historical stability could completely fall apart.

On top of that, even though GDP and worker productivity have risen over the decades, many workers, especially those in low and middle-income jobs, haven’t seen their wages keep up. Since the 80s, a bigger share of the productivity gains has gone to capital owners, executives, and highly skilled workers, leaving others behind and deepening income inequality. Declining union membership, globalization, and shifts in labor markets have further eroded workers’ bargaining power, lowering their share of income—even in industries where technology is designed to work alongside people.