3 Answers sorted by

Ω102011

Alright, I think we have an answer! The conjecture is false.

Counterexample: suppose I have a very-high-capacity information channel (N bit capacity), but it's guarded by a uniform random n-bit password. O is the password, A is an N-bit message and a guess at the n-bit password. Y is the N-bit message part of A if the password guess matches O; otherwise, Y is 0.

Let's say the password is 50 bits and the message is 1M bits. If A is independent of the password, then there's a chance of guessing the password, so the bitrate will be about * 1M , or about one-billionth of a bit in expectation.

If A "knows" the password, then the capacity is about 1M bits. So, the delta from knowing the password is a lot more than 50 bits. It's a a multiplier of , rather than an addition of 50 bits.

This is really cool! It means that bits of observation can give a really ridiculously large boost to a system's optimization power. Making actions depend on observations is a potentially-very-big game, even with just a few bits of observation.

Credit to Yair Halberstadt in the comments for the attempted-counterexamples which provided stepping stones to this one.

This is interesting, but it also feels a bit somehow like a "cheat" compared to the more "real" version of this problem (namely, if I know something about the world and can think intelligently about it, how much leverage can I get out of it?).

The kind of system in which you can pack so much information in an action and at the cost of a small bit of information you get so much leverage feels like it ought to be artificial. Trivially, this is actually what makes a lock (real or virtual) work: if you have one simple key/password, you get to do whatever with t...

The new question is: what is the upper bound on bits of optimization gained from a bit of observation? What's the best-case asymptotic scaling? The counterexample suggests it's roughly exponential, i.e. one bit of observation can double the number of bits of optimization. On the other hand, it's not just multiplicative, because our xor example at the top of this post showed a jump from 0 bits of optimization to 1 bit from observing 1 bit.

*

Ω350Eliminating G

The standard definition of channel capacity makes no explicit reference to the original message ; it can be eliminated from the problem. We can do the same thing here, but it’s trickier. First, let’s walk through it for the standard channel capacity setup.

Standard Channel Capacity Setup

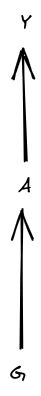

In the standard setup, cannot depend on , so our graph looks like

… and we can further remove entirely by absorbing it into the stochasticity of .

Now, there are two key steps. First step: if is not a deterministic function of , then we can make a deterministic function of without reducing . Anywhere is stochastic, we just read the random bits from some independent part of instead; will have the same joint distribution with any parts of which was reading before, but will also potentially get some information about the newly-read bits of as well.

Second step: note from the graphical structure that mediates between and . Since is a deterministic function of and mediates between and , we have .

Furthermore, we can achieve any distribution (to arbitrary precision) by choosing a suitable function .

So, for the standard channel capacity problem, we have , and we can simplify the optimization problem:

Note that this all applies directly to our conjecture, for the part where actions do not depend on observations.

That’s how we get the standard expression for channel capacity. It would be potentially helpful to do something similar in our problem, allowing for observation of .

Our Problem

The step about determinism of carries over easily: if is not a deterministic function of and , then we can change to read random bits from an independent part of . That will make a deterministic function of and without reducing .

The second step fails: does not mediate between and .

However, we can define a “Policy” variable

is also a deterministic function of , and does mediate between G and Y. And we can achieve any distribution over policies (to arbitrary precision) by choosing a suitable function .

So, we can rewrite our problem as

In the context of our toy example: has two possible values, and . If takes the first value, then is deterministically 0; if takes the second value, then is deterministically 1. So, taking the distribution to be 50/50 over those two values, our generalized “channel capacity” is at least 1 bit. (Note that we haven’t shown that no achieves higher value in the maximization problem, which is why I say “at least”.)

Back to the general case: our conjecture can be expressed as

where the first optimization problem uses the factorization

and the second optimization problem uses the factorization

30

I didn't think much about the mathematical problem, but I think that the conjecture is at least wrong in spirit, and that LLMs are good counterexample for the spirit. An LLM by its own is not very good at being an assistant, but you need pretty small amounts of optimization to steer the existing capabilities toward being a good assistant. I think about it as "the assistant was already there, with very small but not negligible probability", so in a sense "the optimization was already there", but not in a sense that is easy to capture mathematically.

So there’s this thing where a system can perform more bits of optimization on its environment by observing some bits of information from its environment. Conjecture: observing an additional N bits of information can allow a system to perform at most N additional bits of optimization. I want a proof or disproof of this conjecture.

I’ll operationalize “bits of optimization” in a similar way to channel capacity, so in more precise information-theoretic language, the conjecture can be stated as: if the sender (but NOT the receiver) observes N bits of information about the noise in a noisy channel, they can use that information to increase the bit-rate by at most N bits per usage.

For once, I’m pretty confident that the operationalization is correct, so this is a concrete math question.

Toy Example

We have three variables, each one bit: Action (A), Observable (O), and outcome (Y). Our “environment” takes in the action and observable, and spits out the outcome, in this case via an xor function:

Y=A⊕O

We’ll assume the observable bit has a 50/50 distribution.

If the action is independent of the observable, then the distribution of outcome Y is the same no matter what action is taken: it’s just 50/50. The actions can perform zero bits of optimization; they can’t change the distribution of outcomes at all.

On the other hand, if the actions can be a function of O, then we can take either A=O or A=¯O (i.e. not-O), in which case Y will be deterministically 0 (if we take A=O), or deterministically 1 (for A=¯O). So, the actions can apply 1 bit of optimization to Y, steering Y deterministically into one half of its state space or the other half. By making the actions A a function of observable O, i.e. by “observing 1 bit”, 1 additional bit of optimization can be performed via the actions.

Operationalization

Operationalizing this problem is surprisingly tricky; at first glance the problem pattern-matches to various standard info-theoretic things, and those pattern-matches turn out to be misleading. (In particular, it’s not just conditional mutual information, since only the sender - not the receiver - observes the observable.) We have to start from relatively basic principles.

The natural starting point is to operationalize “bits of optimization” in a similar way to info-theoretic channel capacity. We have 4 random variables:

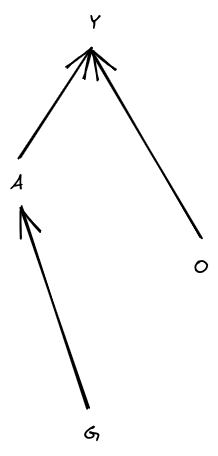

Structurally:

(This diagram is a Bayes net; it says that G and O are independent, A is calculated from G and O and maybe some additional noise, and Y is calculated from A and O and maybe some additional noise. So, P[G,O,A,Y]=P[G]P[O]P[A|G,O]P[Y|A,O].) The generalized “channel capacity” is the maximum value of the mutual information I(G;Y), over distributions P[A|G,O].

Intuitive story: the system will be assigned a random goal G, and then take actions A (as a function of observations O) to steer the outcome Y. The “number of bits of optimization” applied to Y is the amount of information one could gain about the goal G by observing the outcome Y.

In information theoretic language:

Then the generalized “channel capacity” is found by choosing the encoding P[A|G,O] to maximize I(G;Y).

I’ll also import one more assumption from the standard info-theoretic setup: G is represented as an arbitrarily long string of independent 50/50 bits.

So, fully written out, the conjecture says:

Also, one slightly stronger bonus conjecture: Δ is at most I(A;O) under the unconstrained maximal P[A|G,O].

(Feel free to give answers that are only partial progress, and use this space to think out loud. I will also post some partial progress below. Also, thankyou to Alex Mennen for some help with a couple conjectures along the path to formulating this one.)