I asked students if they would want to press a magic button that would permanently delete all social media and messaging apps from the phones of their friend groups if nobody knew it was them. I got only a couple takers. There was more (but far from majority) enthusiasm for deleting all such apps from the whole world. I suspect rates would have been higher if I had asked this as an anonymous written question, but probably not much higher.

An anonymous response, or better yet, a list deletion or Bayesian truth serum question, would certainly be worth doing.

It's also striking that you get anywhere close to a majority for that question. (And consistent with Haidt and the other willingness-to-pay experiment about the harms of social media being a systemic problem, where you are unable to optout on an individual, or even very narrow friend-group basis, because that still leaves the rest of society using it.) Imagine asking that question about, say, indoor plumbing or electricity or vaccines? I suspect even much more controversial technologies like cars or video games would still get many fewer votes for deletion at any scale.

if asked about recommendation algoritms, I think it might be much higher - given a basic understanding of what they are, addictiveness, etc

Looking back, I was surprised by the (unflattering, in my opinion) degree to which LWers saw this data as strong confirmation of their hypotheses about phones being the source of the ills they see in our schools and our young.

I thought it was much more of a mixed picture despite -- or perhaps because -- the numbers were significantly higher than I, a veteran teacher, had expected: If I had been told the previous summer that "next year, we're giving you a cohort of students with this phone usage profile", I might have braced for a crop of students that came off as especially scatterbrained. But overall, these students -- even most of the high-receivers on the left of the chart -- seemed to me about as well adjusted as teenagers of yesteryear and, I would say, better adjusted than the students I remember from the early days of pre-smartphone texting going mainstream. (There's probably a thread to pick there about messages being more alive among teens with vibrant in-person social lives.)

The update for me from this experient was more like, "Huh, I guess notifications are just sort of a background hum of modern existence now. If adults can largely manage to be productive in this environment, maybe I shouldn't be so surprised that young people who grew up in it can, too." This it's-just-a-different-world-now feeling was accentuated by the fact that the school itself was now behind a high fraction of notifications for the median student.

I'm wary of anecdotal clickbait-ish tales of "This school locked away phones, and something miraculous happened" because I would expect a honeymoon phase where an engaging teacher can step in and fill any real attention void before the more traditonal expressions of mental exhaustion and apathy can assert themselves.

To change my mind about this, I would need to linger in the counterfactual world where the students I had known from the start to be actually, problematically distracted by their devices were permanently deprived of them. My mental simulation of that world sees about half of these students gradually becoming traditional excessively-chatty-in-class types, and most of the rest daydreaming, sleeping, or checking out in some other way. To the extent that a busy life on a phone keeps a teen's mind active, it might actually be an improvement?

Strong upvoted, thank you for the serious contribution.

Children spending 300 hours per year learning math, on their own time and via well-designed engaging video-game-like apps (with eg AI tutors, video lectures, collaborating with parents to dispense rewards for performance instead of punishments for visible non-compliance, and results measured via standardized tests), at the fastest possible rate for them (or even one of 5 different paces where fewer than 10% are mistakenly placed into the wrong category) would probably result in vastly superior results among every demographic than the current paradigm of ~30-person classrooms.

in just the last two years I've seen an explosion in students who discreetly wear a wireless earbud in one ear and may or may not be listening to music in addition to (or instead of) whatever is happening in class. This is so difficult and awkward to police with girls who have long hair that I wonder if it has actually started to drive hair fashion in an ear-concealing direction.

This isn't just a problem with the students; the companies themselves end up in equilibria where visibly controversial practices get RLHF'd into being either removed or invisible (or hard for people to put their finger on). For example, hours a day of instant gratification reducing attention spans, except unlike the early 2010s where it became controversial, reducing attention spans in ways too complicated or ambiguous for students and teachers to put their finger on until a random researcher figures it out and makes the tacit explicit. Or another counterintuitive vector could be the democratic process of public opinion turns against schooling, except in a lasting way. Or the results of multiple vectors like these overlapping.

I don't see how the classroom-based system, dominated entirely by bureaucracies and tradition, could possibly compete with that without visibly being turned into swiss cheese. It might have been clinging on to continued good results from a dwindling proportion of students who were raised to be morally/ideologically in favor of respecting the teacher more than the other students, but that proportion will also decline as schooling loses legitimacy.

Regulation could plausibly halt the trend from most or all angles, but it would have to be the historically unprecedented kind of regulation that's managed by regulators with historically unprecedented levels of seriousness and conscientiousness towards complex hard-to-predict/measure outcomes.

Children spending 300 hours per year learning math, on their own time and via well-designed engaging video-game-like apps (with eg AI tutors, video lectures, collaborating with parents to dispense rewards for performance instead of punishments for visible non-compliance, and results measured via standardized tests), at the fastest possible rate for them (or even one of 5 different paces where fewer than 10% are mistakenly placed into the wrong category) would probably result in vastly superior results among every demographic than the current paradigm of ~30-person classrooms.

This sounds great.

Googling "math tutor ai" already gives a bunch of competing suggestions. I wonder how well they work though.

Students were instructed to have their phones on their desks and turned on. For extra amusement, they were invited (but not required) to turn on audible indicators. They were asked to tally each notification received and log it by app.

Just checking, were they counting pull notifications as well as push?

- Push notifications: All notifications that appeared on your lock screen / buzz your phone / make a noise.

- Pull notifications: Any in-app notifications that don't have the above effects, but that you see if you choose to open the app.

For instance my FB app has like 5-10 'notifications' for me when I check it once a day, but I only find out when I check it, there are no badges and nothing appears on my lock screen.

I have hundreds of pull notifications per day in my slack app, but I get close to zero push notifications (e.g. yesterday I got ~20).

They should not have been counting pull notifications, as they were instructed to not engage with their phones during the experiment except to maybe see what caused a vibration or ding. I don't think students think of pull notifications as real notifications the way we were using the word. They were logging the notifications they could notice while their phone flat was flat on their desk not being touched.

Thanks for clarifying, that's what I was expecting.

I just needed to check, because if I'm getting 20/day, and the peak student is getting 450/hour, then that's like 300x difference in terms of notifications, and that really is an extremely different experience of life. Even the mean kid is having a ~30x different experience. I wonder whether I would be able to have time to think if that was my life.

From chatting with those peak students during the experiment, I think their experience is more like being in a cafeteria abuzz with the voices of friends and acquaintances. At some point, you're not even trying to follow every conversation, but are just maintaining some vague awareness of the conversations that are taking place and jumping in when you feel like it. People can and do think about other things in a noisy cafeteria. Some even read books! The brain can filter out a constant buzz. It's just wind blowing through the trees.

The upper middle zone where it's still possible to try to follow everything (and maybe even reply) looked like more of an attention trap, and was where I was more likely to find that handful of students I already knew had a problem. The FOMO is probably more distracting than the notifications themselves.

At my school all the students have to deposit their cell phones into pouches at the office the beginning of the day.. cell phone strictness alone does not create interpersonal chatter. You just also spend a lot of time and work creating an actual culture of conversation. It's an explicitly taught skill!

Your data on the elasticity of behavior matches my experience well..

In this new era where AI can write their essays, solve their math problems, draw their art, compose their music — and yes, even become their "friends" who distract them with notifications during class — I expect this disconnect to grow.

Do you have numbers on how many students were using AI friend apps?

No. Everyone seemed to know what they were, because they all claimed to know someone who uses them. But I don't recall anyone ever admitting to being such a someone. I sense there's a bit of a stigma around them.

This was really interesting, although it made think differently from you in some points, maybe because of the generation difference.

Let's be honest, at school, we just spent most of our times bored, or learning something we did not want to. Being of the generation that was born with phones, it was not as if I was sucked into a blackhole of information, I WANTED to somehow optimize my time with something I found to be better. This is what justified boredom.

We all have this subconscious idea of time optimisation. And in every class I had back in my mind the same mental dialogue "when I get home, I'll just watch a YouTube video about this theme, and I'll probably learn this 5x faster and better than here". Now with AI, I think you can not only learn faster, but personally tailor how and what you want to be taught much more efficiently. So indeed, the bar for teachers have gone pretty high, and we are just getting started in the AI revolution. Even me, in my fourth year of medschool get caught myself drifting and instead asking for an AI to explain something generally complex, and have a pretty satisfying discussion with it.

My conclusion from this is that if AI at the level of gpt-4o was used as a teaching tool in itself, it might decrease this "wandering mind" that alumni tend to have in normal classes, because of the time optimisation. When you use AI, it's all about input and output, you have to engage with it to receive. Differently from normal human teaching in a class with >≈ 40 students, where the teacher will just keep talking, regardless if you are following or interested.

It seems like the students think that eliminating the distractions wouldn't improve how much they learn in class. That sounds ridiculous to me, but public school classrooms are a weird environment that already aren't really set up well to teach anyone anything, so maybe it could be true. Is it credible?

It is credible that eliminating all preventable distractions (phones, earbuds, etc.) wouldn't improve learning much. As a teen, I bet you were distracted during class by all sorts of things contained entirely within your head. I know I was!

There's a somewhat stronger case that video games and social media have given students more things to be preoccupied about even if you make these things inaccessible during class. But I also think that just being a hormonal teen is often distracting enough to fill in any attention vacancies faster than the median lesson can.

The LessWrong Review runs every year to select the posts that have most stood the test of time. This post is not yet eligible for review, but will be at the end of 2025. The top fifty or so posts are featured prominently on the site throughout the year.

Hopefully, the review is better than karma at judging enduring value. If we have accurate prediction markets on the review results, maybe we can have better incentives on LessWrong today. Will this post make the top fifty?

Introduction

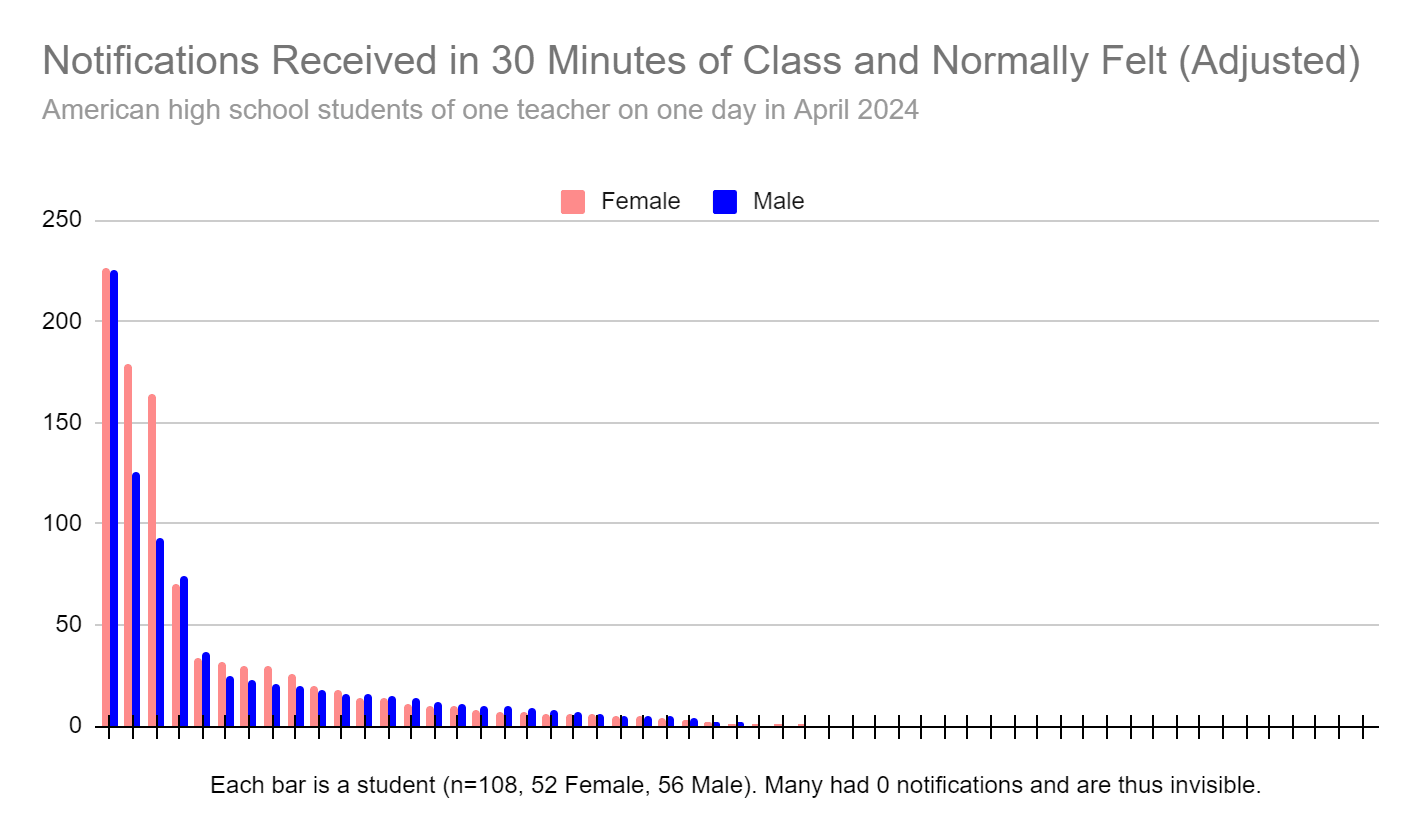

If you are choosing to read this post, you've probably seen the image below depicting all the notifications students received on their phones during one class period. You probably saw it as a retweet of this tweet, or in one of Zvi’s posts. Did you find this data plausible, or did you roll to disbelieve? Did you know that the image dates back to at least 2019? Does that fact make you more or less worried about the truth on the ground as of 2024?

Last month, I performed an enhanced replication of this experiment in my high school classes. This was partly because we had a use for it, partly to model scientific thinking, and partly because I was just really curious. Before you scroll past the image, I want to give you a chance to mentally register your predictions. Did my average class match the roughly 1,084 notifications I counted on Ms. Garza's viral image? What does the distribution look like? Is there a notable gender difference? Do honors classes get more or fewer notifications than regular classes? Which apps dominate? Let's find out!

Before you rush to compare apples and oranges, keep in mind that I don't know anything about Ms. Garza's class -- not the grade, the size, or the duration of her experiment. That would have made it hard for me to do a true replication, and since I saw some obvious ways to improve on her protocol, I went my own way with it.

Procedure

We opened class with a discussion about what we were trying to measure and how we were going to measure it for the next 30 minutes. Students were instructed to have their phones on their desks and turned on. For extra amusement, they were invited (but not required) to turn on audible indicators. They were asked to tally each notification received and log it by app. They were instructed to not engage with any received notifications, and to keep their phone use passive during the experiment, which I monitored.

While they were not to put their names on their tally sheets, they were asked to provide some metadata that included (if comfortable) their gender. (They knew that gender differences in phone use and depression were a topic of public discussion, and were largely happy to provide this.)

To give us a consistent source of undemanding background "instruction" — and to act as our timer — I played the first 30 minutes of Kurzgesagt's groovy 4.5 Billion Years in 1 Hour video. Periodically, I also mingled with students in search of insights, which proved highly productive.

After the 30 minutes, students were charged with summing their own tally marks and writing totals as digits, so as to avoid a common issue where different students bundle and count tally clusters differently.

Results

Below are the two charts from our experiment that I think best capture the data of interest. The first is more straightforward, but I think the second is a little more meaningful.

Ah! So right away we can see a textbook long-tailed distribution. The top 20% of recipients accounted for 75% of all received notifications, and the bottom 20% for basically zero. We can also see that girls are more likely to be in that top tier, but they aren't exactly crushing the boys.

But do students actually notice and get distracted by all of these notifications? This is partly subjective, obviously, but we probably aren't as worried about students who would normally have their phones turned off or tucked away in their backpacks on the floor. So one of my metadata questions asked them about this. The good rapport I enjoy with my students makes me pretty confident that I got honest answers — as does the fact that the data doesn't change all that much when I adjust for this in the chart below.

The most interesting difference in the adjusted chart is that the tail isn't nearly as long; under these rules, nearly half of students "received" no notifications during the experiment. The students most likely to keep their phones from distracting them were the students who weren't getting many notifications in the first place.

Since it mostly didn't matter, I stuck with the unadjusted data for the calculations below, except where indicated.

Do my numbers make Ms. Garza's numbers plausible? Yes! If my experiment had run for a 55 minute class period, that would be 37.2 notifications per student. Assuming a larger class of 30 students, that would be 1,116 notifications total, remarkably close to Ms. Garza's 1,084-ish.

Do honors classes get more or fewer notifications than regular classes? While I teach three sections of each, this question is confounded a bit by the fact that honors classes tend to skew female, so let's break down the averages and medians by gender:

So... it's interesting, but complicated. For girls, the main difference seems to come down to a few of the heaviest female recipients being in honors classes, blowing up their classes' averages despite the medians being identical. For boys, there seems to be a significantly higher median in the non-honors classes, which is less likely to be the result of just a few boys being in one class or the other.

Which apps dominate? Instagram and Snapchat were nearly tied, and together accounted for 46% of all notifications. With vanilla text messages accounting for an additional 35%, we can comfortably say that social communications account for the great bulk of all in-class notifications.

There was little significant gender difference in the app data, with two minor apps accounting for the bulk of the variation: Ring (doorbell and house cameras) and Life 360 (friend/family location tracker), each of which sent several notifications to a few girls. ("Yeah," said girls during our debriefing sessions, "girls are stalkers." Other girls nodded in agreement.)

Notifications from Discord, Twitch, or other gaming-centric services were almost exclusively received by males, but there weren't enough of these to pop out in the data.

Insights from talking to individual students

Discussion

At the end of our 30 minutes, we had some whole-class follow-up discussions. I will layer some of my own thoughts onto the takeaways:

Conclusion

The state of classroom distraction is a complicated one. Students are incredibly varied in their level of digital connectivity in ways that are not obviously correlated with gender or academic achievement. I didn't try to explore any mental health angles, but I also didn't see any obvious trends in the personalities of students who were highly or weakly tied to their social media.

My sense is that the harms of connectivity, like the level of connectivity, are also highly variable from student to student, and not strongly correlated with the notification rate. Most of my students (even among top notification recipients) seem as well-adjusted with regards to their technology as professional adults. Only a few have an obvious problem, and they will often admit to it. What's not clear to me is whether those maladjusted teens would not, in the absence of phones, find some other outlet to distract themselves.

In any event, the landscape of distraction is constantly shifting. I've started to see more students who can skillfully text on a smartwatch, and in just the last two years I've seen an explosion in students who discreetly wear a wireless earbud in one ear and may or may not be listening to music in addition to (or instead of) whatever is happening in class. This is so difficult and awkward to police with girls who have long hair that I wonder if it has actually started to drive hair fashion in an ear-concealing direction. It's also difficult to police earbuds when some students are given special accommodations that allow them to wear one, and I predict that if we ever see an explosion of teenagers with cool hearing aids it will be because this gives them full license to listen to whatever they want whenever they want.

The constant, for at least a little longer, is a human teacher in the classroom. Teachers that students find interesting (or feel they are getting value out of) can continue to command attention. But the bar is going up. This may be especially challenging for new teachers, who are not only in increasingly short supply, but anecdotally seem more likely to bounce off of the profession than in years past.

We must also reflect that distracting technology isn't the only factor driving student apathy, and it never was. Disinterest partly stems from the basic psychology of an age group that struggles to feel like anything after tomorrow will ever be real. But there's also the question of what the day after tomorrow will bring. For as long as kids have been compelled to attend school, we've had students who feel a disconnect between what school is providing and what their adult world will actually expect of them. In this new era where AI can write their essays, solve their math problems, draw their art, compose their music — and yes, even become their "friends" who distract them with notifications during class — I expect this disconnect to grow.